Nazi Germany Invades the Soviet Union (June - December, 1941)

In Mein Kampf and in numerous speeches, Adolf Hitler claimed that the German population needed more living space. Hitler's Lebensraum policy was mainly directed at the Soviet Union. He was especially interested in the Ukraine where he planned to develop a German colony. The system would be based on the British occupation of India: "What India was for England the territories of Russia will be for us... The German colonists ought to live on handsome, spacious farms. The German services will be lodged in marvellous buildings, the governors in palaces... The Germans - this is essential - will have to constitute amongst themselves a closed society, like a fortress. The least of our stable-lads will be superior to any native." (1)

Hitler had made the same point in Mein Kampf (1925): "We take up where we broke off six hundred years ago. We stop the endless movement towards the south and west of Europe, and turn our gaze towards the lands of the east. At long last we put a stop to the colonial and commercial policy of pre-war days and pass over to the territorial policy of the future. But when we speak of new territory in Europe today we must think principally of Russia and her border vassal states. Destiny itself seems to wish to point out the way to us here... This colossal Empire in the east is ripe for dissolution, and the end of the Jewish domination in Russia will also be the end of Russia as a state." (2)

In a series of speeches in the 1920s he talked about the expansion of German "living-space" at the expense of Russia. In a speech in 1922 he argued that only through the destruction of Bolshevism could Germany be saved. At the same time, through expansion into the Soviet Union itself, would bring the territory which Germany needed. As early as December 1922, he talked about the need for an alliance with Britain in its dealing with the Soviet Union. He told Eduard Scharrer, an early supporter of the Nazi Party: "Germany would have to adapt herself to a purely continental policy, avoiding harm to English interest. The destruction of Russia with the help of England would have to be attempted. Russia would give Germany sufficient land for German settlers and a wide field of activity for German industry. Then England would not interrupt us in our reckoning with France." (3)

Adolf Hitler & the Soviet Union

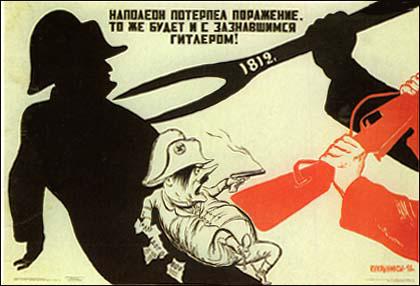

By the spring of 1941 it became clear that Britain was unwilling to surrender. His strategy of bombing Britain into capitulation had ended in failure. As Alan Bullock has argued: "Forced to recognize that the British were not going to be bluffed or bombed into capitulation, Hitler convinced himself that Britain was already virtually defeated. She was certainly not in a position, in the near future, to threaten his hold over the Continent. Why then waste time forcing the British to admit that Germany should have a free hand on the Continent, when this was already an established fact to which the British could make no practical objection?" (4)

In another speech Hitler argued: "If only I could make the German people understand what this space means for our future! We must no longer allow Germans to emigrate to America. On the contrary, we must attract the Norwegians, the Swedes, the Danes, and the Dutch into our Eastern territories. They'll become members of the German Reich... The German colonist ought to live on handsome, spacious farms... What exists beyond that will be another world in which we mean to let the Russians live as they like. It is merely necessary that we should rule them." (5)

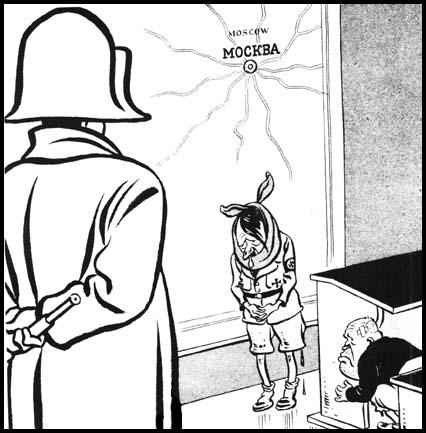

Hitler believed that the Blitzkrieg tactics employed against the other European countries could not be used as successfully against the Soviet Union. He conceded that due to its enormous size, the Soviet Union would take longer than other countries to occupy. However, he was confident it could still be achieved during the summer months of 1941. (6) Hitler's plan was to attack the Soviet Union in three main army groups: in the north towards Leningrad, in the centre towards Moscow and in the south towards Kiev. The German High Command argued that the attack should concentrate on Moscow, the Soviet Union's main communication centre. Hitler rejected the suggestion and was confident that the German army could achieve all three objectives before the arrival of winter. His original idea was to start the campaign on 15th May 1941, but it was delayed to June because Hitler wanted to make sure he had enough German soldiers in German-occupied Poland, to achieve an easy victory. (7)

Hitler believed that after a series of sharp defeats, the government of Joseph Stalin would fall. Hitler suggested to General Alfred Jodl: "We have only to kick in the door and the whole rotten structure will come crashing down." Other leading military figures were also confident of a quick victory. Field-Marshal Paul von Kleist told Basil Liddell Hart after the war: "Hopes of victory were largely built on the prospect that the invasion would produce a political upheaval in Russia... Too high hopes were built on the belief that Stalin would be overthrown by his own people if he suffered heavy defeats. The belief was fostered by the Führer's political advisers, and we, as soldiers, didn't know enough about the political side to dispute it." (8)

Joachim von Ribbentrop, the German foreign minister, was against the proposed invasion of the Soviet Union: "I can summarize my opinion on a German-Russian conflict in one sentence: if every burned out Russian city was worth as much to us as a sunk English battleship, then I would be in favour of a German-Russian war in this summer; I think though that we can win over Russia only militarily but that we should lose economically. One can find it enticing to give the Communist system its death blow and perhaps say too that it lies in the logic of things to let the European-Asiatic continent now march forth against Anglo-Saxondom and its allies. But only one thing is decisive: whether this undertaking would hasten the fall of England.... A German attack on Russia would only give a lift to English morale. It would be evaluated there as German doubt of the success of our war against England. We would in this fashion not only admit that the war would still last a long time, but we could in this way actually lengthen instead of shorten it." (9)

Joseph Goebbels disagreed with Ribbentrop and Hitler because he expected a quick victory: "The Führer thinks that the action will take only 4 months; I think - even less. Bolshevism will collapse as a house of cards. We are facing an unprecedented victorious campaign. Cooperation with Russia was in fact a stain on our reputation. Now it is going to be washed out. The very thing we were struggling against for our whole lives, will now be destroyed. I tell this to the Führer and he agrees with me completely." (10)

Hitler was aware that the Red Army lacked experienced officers. It is estimated that during the Great Purge an estimated 36,671 officers were executed, imprisoned or dismissed and out of the 706 officers of the rank of brigade commander and above, only 303 remained untouched. The most prominent victim was Marshal Mikhail Tukhachevsky, the leading advocate of mobile warfare. His arrest and execution represented the deliberate destruction of the Red Army's operational thinking. By 1941 most of the sacked officers were reinstated, but the psychological effect had been devastating. (11)

Hitler was aware of the numerical superiority of the Russians, but he was certain that the political weakness of the Soviet government, together with the technical superiority of the Germans, would give him a quick victory. "Once he had extended his power to the Urals and the Caucasus, Hitler calculated, he would have established his empire upon such solid foundations that Britain, even if she continued the war and even if the United States intervened on her side, would be unable to make any impression on it. Far from being a desperate expedient forced on him by the frustration of his plans for the defeat of Britain, the invasion of Russia represented the realization of those imperial dreams which he had sketched in the closing section of Mein Kampf and elaborated in the fireside circle of the Berghof." (12)

Hitler tried to persuade his military commanders that invading the Soviet Union would lead to military success: "It was the same with the other high commanders. We were told the Russian armies were about to take the offensive, and it was essential for Germany to remove the menace. It was explained to us that the Führer could not proceed with other plans while this threat loomed dose, as too large a part of the German forces would be pinned down in the east keeping guard. It was argued that attack was the only way for us to remove the risks of a Russian attack." (13)

Joseph Stalin and the Defence of the Soviet Union

Stalin signed the Nazi-Soviet Pact on 23rd August, 1939. He did not trust Hitler but thought it would give him enough time to build up Soviet defences. However, Soviet military planning had been based on the assumption that the German Army would encounter more effective resistance from the French armed forces. After the French surrender in May 1940, Soviet experts suggested that Britain would only survive for a couple of months and that Hitler would turn his attention to the Soviet Union. Stalin told his military leaders: "We're not ready for war of the kind being fought between Germany and England". (14)

Vyacheslav Molotov, the Commissar of Foreign Affairs, pointed out that "we would be able to confront the Germans on an equal basis only by 1943." Stalin main objective was to keep out of a war with Germany for the next two years. He told Hitler that Soviet expansionism was a defunct aspiration. Stalin told Georgi Dimitrov, the head of Comintern: "The International was created in Marx's time in the expectation of an approaching international revolution. The Comintern was created in Lenin's time at an analogous moment. Today, national tasks emerge for each country as a supreme priority. Do not hold on tight to what was yesterday." (15)

Stalin admitted in a speech to graduates of the Military Academy in Moscow: "War with Germany is inevitable. If comrade Molotov can manage to postpone the war for two or three months through the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, that will be our good fortune, but you yourselves must go off and take measures to raise the combat readiness of our forces... Until now we have conducted a peaceful, defensive policy and we've also educated our army in this spirit. True, we've earned something for our labours by conducting a peaceful policy. But now the situation must be changed. We have a strong and well-armed army." (16)

Stalin's priority in the summer of 1941 was to avoid giving Hitler a reason to start a war. General Georgy Zhukov disagreed with Stalin's policy of appeasement and was in favour of invading Nazi Germany. Stalin angrily replied: "What are you up to? Have you come here to scare us with the idea of war or is it that you really want a war? Haven't you got enough medals and titles?" This remark made Zhukov lose his temper but after a brief argument he was forced to accept Stalin's appeasement policy. (17)

Intelligence Sources and the Invasion

Richard Sorge, a secret member of the German Communist Party (KPD), was recruited as a spy for the Soviet Union. In November 1929 Sorge was instructed to join the Nazi Party and not to associate with left-wing activists. To help develop a cover for his spying activities he obtained a post working for the newspaper, Getreide Zeitung. Sorge moved to China and made contact with another spy, Max Klausen. Sorge also met Agnes Smedley, the well-known left-wing journalist. She introduced Sorge to Ozaki Hotsumi, who was employed by the Japanese newspaper, Asahi Shimbun. Later Hotsumi agreed to join Sorge's spy network. (18)

Artur Artuzov, the head of Government Political Administration (GPU) decided to get Sorge to organize a spy network in Japan. As cover Sorge went to Nazi Germany where he was able to get commissions from two newspapers, the Börsen Zeitung and the Tägliche Rundschau. He also got support from the Nazi theoretical journal, Geopolitik. Later he was to get work from the Frankfurter Zeitung. Sorge arrived in Japan in September 1933. He was warned by his spymaster not to have contact with the underground Japanese Communist Party or with the Soviet Embassy in Tokyo. His spy network in Japan include Max Klausen, Ozaki Hotsumi, and two other Comintern agents, Branko Vukelic, a journalist working for the French magazine, Vu, and a Japanese journalist, Yotoku Miyagi, who was employed by the English-language newspaper. (19)

Sorge soon developed good relations with several important figures working at the German Embassy in Tokyo. This included Eugen Ott and the German Ambassador Herbert von Dirksen. This enabled him to find out information about Germany's intentions towards the Soviet Union. Other spies in the network had access to senior politicians in Japan including prime minister Fumimaro Konoye and they were able to obtain good information about Japan's foreign policy. In 1938 Ott replaced Von Dirksen as ambassador. Ott, by now aware that Sorge was sleeping with his wife, let his friend Sorge have "free run of the embassy night and day" as one German diplomat later recalled. (20)

In 1939 Leopold Trepper, an agent for the NKVD, established the Red Orchestra network and organised underground operations in several countries. Richard Sorge was one of its key agents. Others in the group included Ursula Beurton, Harro Schulze-Boysen, Libertas Schulze-Boysen, Arvid Harnack, Mildred Harnack, Sandor Rado, Adam Kuckhoff and Greta Kuckhoff. Arvid Harnack, who worked in the Ministry of Economics, had access to information about Hitler's war plans, and became an important spy. Harnack had a close relationship with Donald Heath, the First Secretary at the US Embassy in Berlin. (21)

On 18th December, 1940, Adolf Hitler signed Directive Number 21, better known as Operation Barbarossa. It included the following: "The German Wehrmacht must be prepared to crush Soviet Russia in a quick campaign even before the conclusion of the war against England. For this purpose the Army will have to employ all available units, with the reservation that the occupied territories must be secured against surprises. For the Luftwaffe it will be a matter of releasing such strong forces for the eastern campaign in support of the Army that a quick completion of the ground operations can be counted on and that damage to eastern German territory by enemy air attacks will be as slight as possible. This concentration of the main effort in the East is limited by the requirement that the entire combat and armament area dominated by us must remain adequately protected against enemy air attacks and that the offensive operations against England, particularly against her supply lines, must not be permitted to break down. The main effort of the Navy will remain unequivocally directed against England even during an eastern campaign. I shall order the concentration against Soviet Russia possibly 8 weeks before the intended beginning of operations. Preparations requiring more time to get under way are to be started now - if this has not yet been done - and are to be completed by May 15, 1941." (22)

Within days Richard Sorge sent a copy of this directive to the NKVD headquarters. Over the next few weeks the NKVD received updates on German preparations. At the beginning of 1941, Harro Schulze-Boysen, sent the NKVD precise information on the operation being planned, including bombing targets and the number of troops involved. In early May, 1941, Leopold Trepper gave the revised date of 21st June for the start of the Operation Barbarossa. On 12th May, Sorge warned Moscow that 150 German divisions were massed along the frontier. Three days later Sorge and Schulze-Boysen confirmed that 21st June would be the date of the invasion of the Soviet Union. (23)

In early June, 1941, Friedrich-Werner Graf von der Schulenburg, the German ambassador, held a meeting in Moscow with Vladimir Dekanozov, the Soviet ambassador in Berlin, and warned him that Hitler was planning to give orders to invade the Soviet Union. Dekanozov, astonished at such a revelation, immediately suspected a trick. When Stalin was told the news he told the Politburo it was all part of a plot by Winston Churchill to start a war between the Soviet Union and Germany: "Disinformation has now reached ambassadorial level!" (24)

On 16th June, 1941, an agent cabled NKVD headquarters that intelligence from the networks indicated that "all of the military training by Germany in preparation for its attack on the Soviet Union is complete, and the strike may be expected at any time.". Later Soviet historians counted over a hundred intelligence warnings of preparations for the German attack forwarded to Stalin between 1st January and 21st June. Others came from military intelligence. Stalin's response to an NKVD report from Schulze-Boysen was "this is not from a source but a disinformer." (25)

Sam E. Woods, commercial attaché in Berlin, developed excellent contacts in the German army command - contacts which brought him close to high-ranking German staff officers opposed to Hitler who knew of the plans for Operation Barbarossa. Woods was able to follow the German preparations from July 1940 until the plans were finalized that December. President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Secretary of State Cordell Hull, agreed that Moscow should be told. Roosevelt ordered, Undersecretary of State Sumner Welles met on 20th March, 1940 with the Soviet Ambassador to Washington, Konstantin A. Umansky, to pass along a warning. (26)

In September 1940, U.S. Army cryptanalysts solved the Japanese diplomatic cipher. Most of the material covered Japanese interests in Asia and the Pacific, but in the last week of March 1941 the cryptanalysts began to produce clear indications of a German invasion. Washington now knew enough about the impending invasion to be very concerned. To reinforce the warning already given to the Soviet ambassador, Welles passed a similar notice through our ambassador in Moscow, who on 15th April, 1941, told a contact in the Foreign Ministry about the plans for Operation Barbarossa. (27)

Winston Churchill sent a personal message to Stalin in April, 1941, explaining how German troop movements suggested that they were about to attack the Soviet Union. However, Stalin was still suspicious of the British and thought that Churchill was trying to trick him into declaring war on Germany. Christopher Andrew points out that he believed this information from Churchill was part of a British political conspiracy: "Churchill's personal warnings to Stalin... only heightened his suspicions... Behind many of the reports of impending German attack Stalin claimed to detect a disinformation campaign by Churchill designed to continue the long-standing British plot to embroil him with Hitler." (28)

Operation Barbarossa

General Walter Warlimont issued an order to all military commanders in the German Army about the proposed occupation of the Soviet Union: (i) Political officials and leaders are to be liquidated. (ii) Insofar as they are captured by the troops, an officer with authority to impose disciplinary punishment decides whether the given individual must be liquidated. For such a decision the fact suffices that he is a political official. (iii) Political leaders in the troops (Red Army) are not recognized as prisoners of war and are to be liquidated at the latest in the prisoner-of-war transit camps. (29)

The NKVD reported that there were no fewer than "thirty-nine aircraft incursions over the state border of the USSR that day on 20th June, 1941, Stalin commented that this must all be part of a plan by Adolf Hitler to extract greater concessions. The Soviet ambassador in Berlin, Vladimir Dekanozov, shared Stalin's conviction that it was all a campaign of disinformation being organized by the British government. Dekanozov even dismissed the report of his own military attaché that 180 German divisions had been deployed along the border. (30)

On 21st June, 1941, a German sergeant deserted to the Soviet forces. He informed them that the German Army would attack at dawn the following morning. War Commissar Marshal Semyon Timoshenko and Chief of Staff General Georgy Zhukov, went to see Stalin with the news. Stalin reaction was the alleged German deserter was an attempt to provoke the Soviet Union. Stalin did agree to send out a message to all his military commanders: "There has arisen the possibility of a sudden German attack on June 21-22... The German attack may begin with provocations... It is ordered to occupy secretly the strong points on the frontier... to disperse and camouflage planes at special airfields... to have all units battle ready... No other measures are to be employed without special orders." (31)

Stalin now went to bed. At 3.30 a.m. Timoshenko received reports of heavy shelling along the Soviet-German frontier. Timoshenko told Zhukov to call Stalin by telephone: "Like a schoolboy rejecting proof of simple arithmetic, Stalin disbelieved his ears. Breathing heavily, he grunted to Zhukov that no counter-measures should be taken... Stalin's only concession to Zhukov was to rise from his bed and return to Moscow by limousine. There he met Zhukov and Timoshenko along with Molotov, Beria, Voroshilov and Lev Mekhlis.... Pale and bewildered, he sat with them at the table clutching an empty pipe for comfort. He could not accept he was wrong about Hitler. He muttered that the outbreak of hostilities must have originated in a conspiracy within the Wehrmacht... Hitler surely doesn't know about it. He ordered Molotov to get in touch with Ambassador Schulenburg to clarify the situation. (32)

Stalin was too shocked and embarrassed to tell the people of the Soviet Union that the country had been invaded by Germany. Vyacheslav Molotov was therefore asked to make the radio broadcast. "Today at four o'clock in the morning, German troops attacked our country without making any claims on the Soviet Union and without any declaration of war... Our cause is just. The enemy will be beaten. We will be victorious." (33)

Stalin retreated to his Blizhnyaya dacha and refused to talk to anyone. Molotov eventually came up with the idea of forming a State Committee of Defence. He persuaded Lavrenty Beria (the head of NKVD), Georgy Malenkov (Secretary of the Central Committee), Kliment Voroshilov (People's Commissar of Defence), Nikolai Voznesensky (State Planning Committee) and Anastas Mikoyan (People's Commissar for External and Internal Trade). It was the first great initiative for years that any of them had taken without seeking his prior sanction. (34)

The group went to see Stalin at his dacha. They found him slumped in an armchair. "Why have you come?" Mikoyan thought Stalin suspected that they were about to arrest him. Molotov explained the need for a State Committee of Defence. Stalin asked: "Who's going to head it?" Molotov suggested that Stalin should be the chairman of the committee. Stalin said: "Good". (35) Beria believed that sooner or later the visitors to the dacha would pay the price just for having seen him in a moment of profound weakness. (36)

On 3rd July, 1941, Stalin gave his first radio broadcast since the invasion: "The Red Army, the Red Navy, and all citizens of the Soviet Union must defend every inch of Soviet soil, must fight to the last drop of blood for our towns and villages, must display the daring, initiative and mental alertness characteristic of our people. In case of forced retreat of Red Army units, all rolling stock must be evacuated, the enemy must not be left a single engine, a single railway truck, not a single pound of grain or gallon of fuel. Collective farmers must drive off all their cattle and turn over their grain to the safe keeping of the state authorities, for transportation to the rear. lf valuable property that cannot be withdrawn, must be destroyed without fail. In areas occupied by the enemy, partisan units, mounted and on foot, must be formed; sabotage groups must be organized to combat enemy units, to foment partisan warfare everywhere, blow up bridges and roads, damage telephone and telegraph lines, set fire to forests, stores and transport. In occupied regions conditions must be made unbearable for the enemy and all his accomplices. They must be hounded and annihilated at every step, and all their measures frustrated." (37)

Initial Attack on the Soviet Union

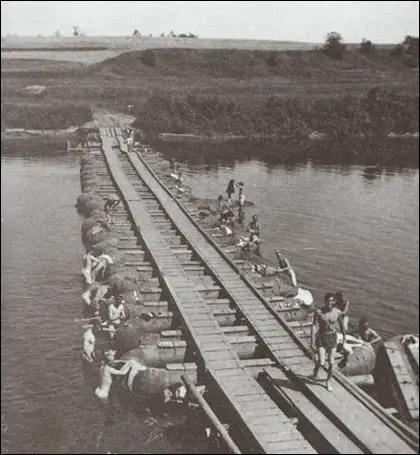

The first objective of the German was to destroy the Red Army stationed on the western border of the Soviet Union. An estimated 3.6 million German and allied soldiers (Finnish and Romanian units) with 600,000 vehicles, 3,600 tanks, 7,100 artillery pieces, and 2,700 aircraft crossed the frontier. Hundreds of troops were hidden in the birch and fir forests of East Prussia and occupied Poland. Opposing these forces were 2.9 million Soviet soldiers of the Western Military District with 15,000 tanks, 35,000 artillery pieces, and approximately 8,500 aircraft. (38)

The invasion of the Soviet Union stretched from Finland to the Black Sea. A massive artillery barrage was followed by rapid advances of the armored and mechanized units. The ultimate objective was "to establish a defence line against Asiatic Russia from a line running from the Volga river to Archangel". Once this had been established the last industrial area left to Russia in the Urals could then be destroyed by the Luftwaffe. (39)

The German Army was accompanied by the Schutzstaffel (SS). Sepp Dietrich, was the commander of the SS Leibstandarte Division. Military commanders were told that captured Soviet political officers, Jews and partisans were to be handed over to the SS. They were told that the war was "the final encounter between two opposing political systems". A "Jurisdiction Order" was issued that deprived Russian civilians of any right of appeal, and effectively exonerated soldiers from crimes committed by them, whether murder, rape or looting. This order was justified on the grounds "that the downfall of 1918, the German people's period of suffering which followed and the struggle against National Socialism - with the many blood sacrifices endured by the movement - can be traced to Bolshevik influence." (40)

Ulrich von Hassell, a former German ambassador to Rome, was shown an order to carry out collective reprisals against civilians. He wrote in his diary: "It makes one's hair stand on end to learn about measures to be taken in Russia, and about the systematic transformation of military law concerning the conquered population into uncontrolled despotism - indeed a caricature of all law. This kind of thing turns the German into a type of being which had existed only in enemy propaganda." (41)

Although a few army commanders were reluctant to distribute the instructions on dealing with the Soviet people, several others added their own racist comments. Field Marshal Walter von Reichenau declared: "The annihilation of those same Jews who support Bolshevism and its organization for murder, the partisans, is a measure of self-preservation." (42) General Erich von Manstein commented: "The Jewish-Bolshevik system must be rooted out once and for all." He then went on to justify "the necessity of harsh measures against Jewry." (43)

Adolf Hitler told his generals that this was to be a "battle between two opposing world views", a "battle of annihilation" against "Bolshevik commissars and the Communist intelligentsia". The military went into Operation Barbarossa with the idea that it was acceptable to carry out these war crimes: "Many historians now argue that Nazi propaganda had so effectively dehumanized the Soviet enemy in the eyes of the Wehrmacht that it was morally anaesthetized from the start of the invasion. Perhaps the greatest measure of successful indoctrination was the almost negligible opposition within the Wehrmacht to the mass execution of Jews, which was deliberately confused with the notion of rear-area security measures against partisans." (44)

On hearing of the early success, Adolf Hitler told his colleagues, "Before three months have passed, we shall witness a collapse of Russia, the like of which has never been seen in history." (45) Joseph Goebbels, the Nazi propaganda minister, was then given permission to make a radio broadcast. He told the German nation: "At this moment a march is taking place that, for its extent, compares with the greatest the world has ever seen. I have decided today to place the fate and future of the Reich and our people in the hands of our soldiers. May God aid us, especially in this fight!" (46)

In the first nine hours of the operation the Luftwaffe carried out pre-emptive sorties that destroyed 1,200 Soviet aircraft, the vast majority on the ground. German pilots could not believe their eyes when they saw hundreds of enemy planes neatly lined up at dispersal beside the runways. Those aircraft that did manage to get off the ground, or arrived from airfields further east, proved easy targets. One squadron officer admitted: "Our pilots feel they are corpses already when they take off." Antony Beevor pointed out: "Some Soviet pilots who either had never learned aerial combat techniques or knew that their obsolete models stood no chance, even resorted to ramming German aircraft. A Luftwaffe general described these air battles against inexperienced pilots as infanticide." (47)

The Luftwaffe also attacked Soviet troops and supply dumps. It reportedly destroyed 1,489 aircraft on the first day of the invasion and over 3,100 during the first three days. Hermann Göring, Minister of Aviation, was so surprised by this news he ordered the figures checked. The Soviets later admitted that they lost 3,922 Soviet aircraft in the first three days against an estimated loss of 78 German aircraft (German Federal Archives suggested the Luftwaffe's lost 63 aircraft for the first day. (48)

The German forces advanced in three main army groups. The north group headed for Leningrad, the centre group for Moscow and the southern forces towards Kiev. Field Marshal Heinrich von Brauchitsch, Commander-in-Chief of the German Army, and Franz Halder, Chief of General Staff, argued that the attack should concentrate on Moscow, the Soviet Union's main communication centre. Hitler rejected the suggestion and was confident that the German Army could achieve all three objectives before the arrival of winter. (49)

Hitler decided to weaken this central thrust, in order to bolster what they saw as subsidiary operations. Hitler believed that once he seized the agricultural wealth of the Ukraine and the Caucasian oilfields, Germany's invincibility was guaranteed. Army Group South under Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt, supported on his right by Hungarians and Romanians was entrusted with this task. The Romanian dictator, Marshal Ion Antonescu, had been delighted when told of Operation Barbarossa ten days before its launch. "Of course I'll be there from the start. When it's a question of action against the Slavs, you can always count on Romania." (50)

The Blitzkrieg tactics in the Soviet Union was a spectacular success. The advance on all fronts was rapid, with most units advancing almost fifty miles a day and a number of encirclement battles ensued. The battles at Bialystock and Minsk were concluded on 9th July with two Soviet armies being destroyed (the 3rd and the 10th). Over 300,000 prisoners were taken; 1,400 guns and 2,500 tanks were also destroyed or captured. When he heard the news Joseph Stalin told Lavrenty Beria: "This is a monstrous crime. Those responsible must lose their heads" and immediately instructed the NKVD to investigate the matter. (51)

General Demitry Pavlov, the Commander of the Soviet Western Front and Major-General Vladimir Efimovich Klimovskikh, were recalled to Moscow. After a meeting with Kliment Voroshilov the two men were charged with being involved in an "anti-Soviet military conspiracy" that had "betrayed the interests of the Motherland, violated the oath of office and damaged the combat power of the Red Army". It was reported that: "A preliminary judicial investigation and determined that the defendants Pavlov and Klimovskikh being: the first - the commander of the Western Front, and the second - the chief of staff of the same front, during the outbreak of hostilities with the German forces against the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, showed cowardice, failure of power, mismanagement, allowed the collapse of command and control, surrender of weapons to the enemy without fighting, willful abandonment of military positions by the Red Army, the most disorganized defense of the country and enabled the enemy to break through the front of the Red Army." Both men were executed on 22nd July, 1941. (52)

General Georgy Zhukov issued a directive that set down "a number of conclusions" following "the experience of three weeks of war against German fascism". His main argument was that the Red Army had suffered from bad communications and over large, sluggish formations, which simply presented a "vulnerable target for air attack". Large armies "made it difficult to organize command and control during a battle, especially because so many of our officers are young and inexperienced". Zhukov therefore suggested it was "necessary to prepare to change to a system of small armies consisting of a maximum of five or six divisions." (53)

The first phase of Operation Barbarossa was concluded with the capture of Smolensk. The Soviet casualties were high (about 300,000 men were taken prisoner) but resistance was incredibly fierce. For the first time the Red Army were able to conduct counter-offensives to blunt the German drive and it took until 10th September, before the city was completely controlled. It has been argued that the battle of Smolensk effectively derailed the German Army's timetable for the capture of Moscow and made it much more difficult to conclude the war before the coming of winter. (54)

General Andrey Yeryomenko, who had replaced General Pavlov, in charge of the Soviet Western Front later wrote: "Having covered every inch of ground with corpses the Nazis broke through to Smolensk. Stubborn fighting for the town proper raged for almost a whole month. The city repeatedly passed from hand to hand. More than one German division found its last resting place in the approaches to Smolensk and in the town itself. Every street and every house was contested by severe fighting and the Nazis paid very heavily for every yard of their advance. Hundreds of German soldiers and officers perished in the waters of the Dnieper River." (55)

German commanders underestimated the fighting ability of the Red Army. "They quickly found that surrounded or outnumbered Soviet soldiers went on fighting when their counterparts from western armies would have surrendered." There were cases of Soviet soldiers fighting for over a month after a town or city had been occupied by the German Army. Although unusual, some of the wounded Soviet soldiers captured managed to survive Nazi prisoner-of-war camps until liberated in 1945. Instead of being treated as heroes, they were sent straight to the Gulag, following Stalin's order that anyone who had fallen into enemy hands was a traitor. (56)

Stalin even disowned his own son, Yakov Dzhugashvili who was captured on 16th July, 1941. He was especially angry that his son was used in an anti-Soviet propaganda campaign. A leaflet was dropped by German aircraft showing a group of German officers talking to Yakov. The caption read: "Stalin's son, Yakov Dzhugashvili, full lieutenant, battery commander, has surrendered. That such an important Soviet officer has surrendered proves beyond doubt that all resistance to the German army is completely pointless. So stop fighting and come over to us." (57)

The German Army managed to trap Soviet troops in the vicinity of Kiev. This encirclement is considered the largest encirclement in the history of warfare. It was an unprecedented defeat for the Red Army. The battle lasted until 26th September, and the Soviets suffered 700,544 casualties, including 616,304 killed, captured or missing during the battle. Nikita Khrushchev, was the political commissar in Kiev and served as an intermediary between the local military commanders and the political rulers in Moscow. He managed to escape from the city but this upset Stalin: "Suddenly I got a telegram from Stalin unjustly accusing me of cowardice and threatening to take action against me. He accused me of intending to surrender Kiev. This is a filthy lie... Kiev fell, not because it was abandoned by our troops who were defending it, but because of the pincer movement which the Germans executed from the north and the south in the regions of Gomel and Kremenchug." (58)

Joseph Stalin now took control of the Soviet war effort. Yakov Chadaev, chief administrative assistant to the Council of People's Commissars, later commented that "Stalin concerned himself, for instance, with the choice of design for a sniper's automatic rifle, and the type of bayonet which could most easily be fixed to it - the knife-blade or the three-edged kind... When I went into Stalin's office I usually found him with Molotov, Beria, and Malenkov... They never asked questions. They sat and listened... Reports coming in from the front as a rule understated our losses and exaggerated those of the enemy." (59)

Marshal Alexander Vasilevsky complained that Stalin was not an easy person to deal with: "Stalin was unjustifiably self-confident, headstrong, unwilling to listen to others; he overestimated his own knowledge and ability to guide the conduct of the war directly. He relied very little on the General Staff and made no adequate use of the skills and experience of its personnel. Often for no reason at all, he would make hasty changes in the top military leadership. Stalin quite rightly insisted that the military must abandon outdated strategic concepts, but he was unfortunately rather slow to do this himself. He tended to favour head-on confrontations." (60)

Although the Soviets had enjoyed a series of victories, German commanders began to feel uneasy about the situation. Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt commented "the vastness of Russia devours us". (61) They were conquering huge territories, yet the horizon seemed just as limitless. By August, 1941, the Red Army had lost over two million men, yet still more Soviet armies appeared. General Franz Halder wrote in his diary: "At the outset of the war, we reckoned on about 200 enemy divisions. Now we have already counted 360." (62)

Field Marshal Heinrich Brauchitsch, Commander in Chief of the German Army, wanted to concentrate on the Moscow line of advance - not for the sake of capturing the capital but because they felt that this line offered the best chance of destroying the mass of Russia's forces which they "expected to find on the way to Moscow". In Hitler's view that course carried the risk of driving the Russians into a general retreat eastwards, out of reach. Brauchitsch agreed this was a danger but thought it was a risk worth taking as Moscow was not only the capital of the Soviet Union, but was a major centre for communications and the armaments industry." (63)

Ferdor von Bock, the Commander-in-Chief of the Centre Army Group and his two panzer commanders, Heinz Guderian and Hermann Hoth, also supported Brauchitsch, in his view that they should concentrating not dispersing, the German effort against the Soviet Union. This was rejected by Hitler, who insisted on ordering part of Bock's mobile forces to assist the northern army group's drive on Leningrad and the rest to wheel south and support the advance into the Ukraine. (64)

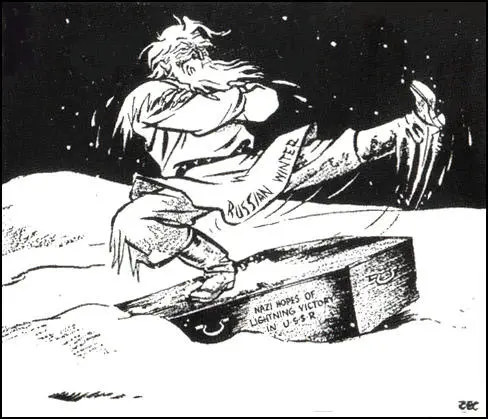

General Paul von Kleist argued: "The main cause of our failure was that winter came early that year, coupled with the way the Russians repeatedly gave ground rather than let themselves be drawn into a decisive battle such as we were seeking." Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt added that they had other problems: "It was increased by the lack of railways in Russia - for bringing up supplies to our advancing troops. Another adverse factor was the way the Russians received continual reinforcements from their back areas, as they fell back. It seemed to us that as soon as one force was wiped out, the path was blocked by the arrival of a fresh force." (65)

It was now clear that the German Army was not strong enough to mount offences in three different directions at once. Casualties had been higher than expected - over 400,000 by the end of August. Engines became clogged with grit from the dust clouds, and broke down constantly, yet replacements were in very short supply. The further they advanced into Russia, the harder it was to bring supplies forward. Panzer columns racing ahead frequently had to stop through lack of fuel. The infantry divisions were marching between 20 and 40 miles a day. According to one source: "The infantry was so tired trudging forwards in full kit that many fell asleep on the march." (66)

Operation Typhoon

It was only on 26th September, 1941, that Hitler gave permission to General Franz Halder to launch Operation Typhoon, the drive to Moscow. However, precious time had been lost. It started well with German forces winning overwhelming victories at Vyazma and Bryansk by the 20th October. Eight Soviet armies commanded by Marshal Semyon Timoshenko were destroyed and 650,000 prisoners taken. The road to Moscow seemed open. (67)

In a speech in Berlin, Hitler boasted: "Behind our troops there already lies a territory twice the size of the German Reich when I came to power in 1933. Today I declare, without reservation, that the enemy in the east has been struck down and will never rise again." (68) Six days later Otto Dietrich, the Reich Press Chief, announced that the war in the east was over: "For all military purposes, Soviet Russia is done with. The British dream of a two-front war is dead." (69)

The German Army was accused of treating Russian prisoners of war very badly. Hermann Göring talked about this to Count Galeazzo Ciano, the Italian Minister of Foreign Affairs: "In the camps for Russian prisoners they have begun to eat each other. This year between twenty and thirty million persons will die of hunger in Russia. Perhaps it is well that it should be so, for certain nations must be decimated. But even if it were not, nothing can be done about it. It is obvious that if humanity is condemned to die of hunger, the last to die will be our two peoples." (70)

Members of the Schutzstaffel (SS) were instructed to wipe out all aspects of communism in the Soviet Union. Communist officials should be executed and, as the Russians were "sub-human", ordinary conventions of behaviour towards captured soldiers did not apply. It is estimated that during the first year of invasion, over a million communists were executed by the SS. Senior officers objected on tactical as well as humanitarian grounds. They argued that knowledge that they faced death or torture would encourage the Soviets to carry on fighting instead of surrendering. (71)

As German troops moved deeper into the Soviet Union, supply lines became longer. Joseph Stalin gave instructions that when forced to withdraw, the Red Army should destroy anything that could be of use to the enemy. The scorched earth policy and the formation of guerrilla units behind the German front lines, created severe problems for the German war machine which was trying to keep her three million soldiers supplied with the necessary food and ammunition. The Soviet soldiers polluted wells during the retreat, while collective farm buildings were destroyed. Food supplies which could not be moved in time were rendered unusable. They poured petrol over the grain supplies and Soviet bombers dropped phosphorus bombs on crops. (72)

In Moscow over one hundred thousand men were mobilized as militia and a quarter of a million civilians, mostly women, began to dig anti-tank ditches. On 15th October, 1941, Stalin told Vyacheslav Molotov, Lazer Kaganovich and Anastas Mikoyan that he proposed to evacuate the whole Government to Kuibyshev, to order the army to defend the capital and keep the Germans fighting until he could throw in his reserves. Molotov and Mikoyan were ordered to manage the evacuation, with Kaganovich provided the transport. Stalin proposed that all the Politburo leave that day and, he added, "I will leave tomorrow morning." (73)

On 17th October changed his mind and decided that he would live in a bomb-proof air-raid shelter positioned under the Kirov Metro Station, while the General Staff worked in the Belorusski Metro Station. On the anniversary of the Russian Revolution, Stalin decided that reinforcements for Zhukov's armies would march through Red Square. He knew the value that newsreel footage of this event would have when distributed round the world. Stalin made a speech where he stated: "If they want a war of extermination they shall have one!" (74)

As they approached Moscow the Germans discovered that the Soviets was deploying a new unconventional weapon. "They found Russian dogs running towards them with a curious-looking saddle holding a load on top with a short upright stick. At first the panzer troops thought that they must be first-aid dogs, but then they realised that the animals had explosives or an anti-tank mine strapped to them. These 'mine-dogs', trained on Pavlovain principles, had been taught to run under large vehicles to obtain their food. The stick, catching against the underside, would detonate the charge. Most of the dogs were shot before they reached their target, but this macabre tactic had an unnerving effect." (75)

The Germans continued their attack, but the autumn rains washed away Russian roads, causing trucks, tanks, and artillery to sink into the mud. Then it began to snow. Confident that the campaign would be finished before winter arrived, Hitler and his staff had made no provision for winter clothing to be issued to the troops. "From early November, the Germans were fighting in sub-zero temperatures, intensified by a bitter wind, the few hours of daylight and the long nights, and fighting in an unfamiliar land far from home against an enemy inured to the conditions, warmly clothed and equipped for winter operations." (76)

By 27th November 1941, some German forces reached the Volga canal, a mere nineteen miles from the northern outskirts of the Russian capital. German patrols had even reached the outer suburbs. All the German advances were halted on 5th December, and preparations were made to retire to defensive positions for the winter. Neither of the primary objectives, Leningrad and Moscow, had been captured. (77)

Field Marshal Ferdor von Bock, was forced to acknowledge at the beginning of December that no further hope of "strategic success" remained. The German's close-fitting, steel-shod jackboots simply hastened the process of frostbite, so they had resorted to stealing the clothes and boots of prisoners of war and civilians. German soldiers "were exhausted and the cases of frostbite - which reached over 100,000 by Christmas - were rapidly outstripping the numbers of wounded." (78)

Lazer Kaganovich was busy arranging for 400,000 fresh troops, 1,000 tanks and 1,000 planes across "the Eurasian wastes, in one of most decisive logistical miracles of the war". (79) On 6th December, 1941, General Georgy Zhukov, commander of the central Soviet forces, launched his winter counter-offensive with fresh divisions transferred from Siberia. Zhukov declared that he would see to it that the troops would "shrink from no sacrifices for the sake of victory." Edvard Radzinsky pointed out: "More than one hundred divisions were involved in the battle. The Germans could not withstand the shock." (80)

Most of the Red Army were equipped for winter warfare, with padded jackets and white camouflage suits. Their heads were kept warm with round fur caps with ear flaps at the side, and their feet with large felt boots. They also had covers for the working parts of their weapons and special oil to prevent the action from freezing. Also, for the first time, the Red Army enjoyed air superiority. The Russians had protected their aircraft from the cold, while the weakened Luftwaffe, operating from improvised landing strips, had to defrost every machine by lighting fires under its engines. (81)

Partisan detachments, organized by officers of NKVD frontier troops, were sent behind enemy lines. Red Army cavalry divisions, mounted on resilient little Cossack ponies. These units would "suddenly appear fifteen miles behind the front, charging artillery batteries or supply depots with drawn sabres and terrifying war-cries". It now became clear that the Soviets planned to encircle the German soldiers. Field Marshal Ferdor von Bock therefore gave orders for the German Army to pull back anything up to a hundred miles. (82)

On 7th December, 1941, 105 high-level bombers, 135 dive-bombers and 81 fighter aircraft attacked the the US Fleet at Pearl Harbour. In their first attack the Japanese sunk the Arizona, Oklahoma, West Virginia and California. The second attack, launched 45 minutes later, hampered by smoke, created less damage. In two hours 18 warships, 188 aircraft and 2,403 servicemen were lost in the attack.The following day, President Franklin D. Roosevelt and a united US Congress declared war on Japan. On 11th December, 1941, Hitler declared war on the United States. (83)

References

(1) Hugh Trevor Roper, Hitler's Table Talk 1941-1944 (1953) page 24

(2) Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf (1925) part II, chapter 14

(3) Ian Kershaw, Hitler 1889-1936 (1998) page 247

(4) Alan Bullock, Hitler: A Study in Tyranny (1962) page 651

(5) Hugh Trevor Roper, Hitler's Table Talk 1941-1944 (1953) page 41

(6) John Simkin, Hitler (1988) page 60

(7) Colin Cross, Adolf Hitler (1973) page 355

(8) Basil Liddell Hart, The Other Side of the Hill (1948) page 259

(9) Joachim von Ribbentrop, letter to Ernst von Weizsäcker, State Secretary at the Foreign Office (29th April, 1941)

(10) Joseph Goebbels, diary entry (July 1941)

(11) John Erikson, The Road to Stalingrad (1975) page 7

(12) Alan Bullock, Hitler: A Study in Tyranny (1962) page 652

(13) General Paul von Kliest was interviewed by Basil Liddell Hart about Operation Barbarossa in his book The Other Side of the Hill (1948) page 257

(14) Gabriel Gorodetsky, Grand Delusion: Stalin and the German Invasion of Russia (2001) pages 129-135

(15) Georgi Dimitrov, Diary: The Years in Moscow (2003) page 302

(16) Joseph Stalin, speech to the Moscow Military Academy (5th May, 1941)

(17) Robert Service, Stalin: A Biography (2004) page 409

(18) Richard Sorge, confession after being interrogated by the Japanese police (October 1941)

(19) Leopold Trepper, The Great Game (1977) pages 73-75

(20) Christopher Andrew & Oleg Gordievsky, KGB: The Inside Story of Its Foreign Operations from Lenin to Gorbachev (1990) page 239

(21) Susan Ottaway, Hitler's Traitors: German Resistance to the Nazis (2003) pages 68-72

(22) Adolf Hitler, Directive Number 21 (8th December, 1940)

(23) Leopold Trepper, The Great Game (1977) page 126

(24) Christopher Andrew & Oleg Gordievsky, KGB: The Inside Story of Its Foreign Operations from Lenin to Gorbachev (1990) page 212

(25) Christopher Andrew, The Mitrokhin Archive (1999) page 122

(26) Waldo Heinrichs, Threshold of War: Franklin D. Roosevelt and American Entry into World War II (1988) pages 21-23

(27) Stephen Budiansky, Battle of Wits: The Complete Story of Codebreaking in World War II (2000) page 196

(28) Christopher Andrew, The Mitrokhin Archive (1999) page 122

(29) General Walter Warlimont, order issued to the German Army (12th May, 1941)

(30) Antony Beevor, Stalingrad (1998) pages 3-4

(31) Adam B. Ulam, Stalin: The Man and his Era (2007) page 537

(32) Robert Service, Stalin: A Biography (2004) page 410

(33) Vyacheslav Molotov, radio broadcast (22nd July, 1941)

(34) Anastas Mikoyan, That's How It Was (1999) page 390

(35) Robert Service, Stalin: A Biography (2004) page 415

(36) Anastas Mikoyan, That's How It Was (1999) page 391

(37) Joseph Stalin, radio speech (3rd July, 1941)

(38) Michael Olive & Robert Edwards, Operation Barbarossa (2012) page vi

(39) Antony Beevor, Stalingrad (1998) page 87

(40) Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel, Jurisdiction Order (13th May, 1941)

(41) Ulrich von Hassell, diary entry (8th April, 1941)

(42) Paul Addison and Angus Calder (editors), Time to Kill, The Soldier's Experience of War (1997) page 270

(43) General Erich von Manstein, memorandum (20th November, 1941

(44) Antony Beevor, Stalingrad (1998) page 15

(45) Lloyd Clark, Kursk: The Greatest Battle (2012) page 12

(46) Joseph Goebbels, radio broadcast (22nd June, 1941)

(47) Antony Beevor, Stalingrad (1998) page 19

(48) Christer Bergström, Barbarossa - The Air Battle (2007) pages 20-23

(49) John Simkin, Hitler (1988) page 60

(50) Paul Schmidt, Hitler's Interpreter: The Secret History of German Diplomacy (1951) page 233

(51) Adam B. Ulam, Stalin: The Man and his Era (2007) page 543

(52) Simon Sebag Montefiore, Stalin: The Court of the Red Tsar (2003) page 377

(53) General Georgy Zhukov, Stavka Directive (15th July, 1941)

(54) Michael Olive & Robert Edwards, Operation Barbarossa (2012) page vii

(55) Andrey Yeryomenko, Strategy and Tactics of the Soviet-German War (1943) page 16

(56) Antony Beevor, Stalingrad (1998) page 26

(57) Edvard Radzinsky, Stalin (1997) page 458

(58) Nikita Khrushchev, Khrushchev Remembers (1971) page 153

(59) Edvard Radzinsky, Stalin (1997) page 451

(60) Marshal Alexander Vasilevsky, The Matter of my Whole Life (1974) page 7

(61) Charles Messenger, The Last Prussian: A Biography of Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt (1991) page 150

(62) General Franz Halder, diary entry (11th August, 1941)

(63) Antony Beevor, Stalingrad (1998) page 32

(64) Alan Bullock, Hitler: A Study in Tyranny (1962) page 653

(65) Basil Liddell Hart, The Other Side of the Hill (1948) page 265

(66) Antony Beevor, Stalingrad (1998) page 32

(67) Michael Olive & Robert Edwards, Operation Barbarossa (2012) page vii

(68) Adolf Hitler, speech in Berlin (3rd October, 1941)

(69) Otto Dietrich, press release (9th October, 1941)

(70) Count Galeazzo Ciano, Diplomatic Papers (1948) pages 464-465

(71) John Simkin, Hitler (1988) page 60

(72) Antony Beevor, Stalingrad (1998) page 87

(73) Simon Sebag Montefiore, Stalin: The Court of the Red Tsar (2003) page 404

(74) Alexander Werth, Russia at War (1964) page 246

(75) Antony Beevor, Stalingrad (1998) page 36

(76) Alan Bullock, Hitler: A Study in Tyranny (1962) page 660

(77) Michael Olive & Robert Edwards, Operation Barbarossa (2012) page vii

(78) Antony Beevor, Stalingrad (1998) page 40

(79) Simon Sebag Montefiore, Stalin: The Court of the Red Tsar (2003) page 410

(80) Edvard Radzinsky, Stalin (1997) pages 468-469

(81) Robert Service, Stalin: A Biography (2004) page 424

(82) Antony Beevor, Stalingrad (1998) page 42

(83) Alan Bullock, Hitler: A Study in Tyranny (1962) page 661

John Simkin