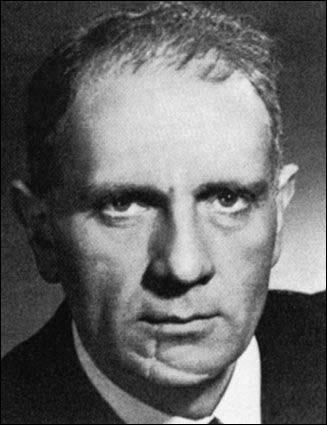

Theodor Haubach

Theodor Haubach was born in Frankfurt am Main, Germany, on 15th September, 1896. He volunteered for the Germany Army during the First World War. While serving on the Western Front he was wounded several times.

In 1919 he went to university where he studied philosophy, sociology, and economics. Haubach joined the Social Democratic Party (SDP) and became socialist youth leader . During this period he became very close to fellow SDP member, Carlo Mierendorff. (1)

Haubach became a journalist and from 1924 to 1929 he was editor of the newspaper Hamburger Echo. Haubach was the leading member of the Reichsbanner Schwarz-Rot-Gold, an association that campaigned in support of the Weimar Republic. He also served as chief press officer of the Prussian government. (2)

After the 1933 General Election, Chancellor Adolf Hitler proposed an Enabling Bill that would give him dictatorial powers. Such an act needed three-quarters of the members of the Reichstag to vote in its favour. All the active members of the Communist Party (KPD), were in prison, in hiding, or had left the country (an estimated 60,000 people left Germany during the first few weeks after the election). This was also true of most of the leaders of the other left-wing party, Social Democrat Party (SDP). Mierendorff refused to go: "We can't just all go to the Riviera." (3)

However, Hitler still needed the support of the Catholic Centre Party (BVP) to pass this legislation. Hitler therefore offered the BVP a deal: vote for the bill and the Nazi government would guarantee the rights of the Catholic Church. The BVP agreed and when the vote was taken on 24th March, 1933, only 94 members of the SDP voted against the Enabling Bill. (4)

Soon afterwards the Communist Party and the Social Democrat Party became banned organisations. Party activists still in the country were arrested. This included Theodor Haubach, Carlo Mierendorff, Wilhelm Leuschner, and Julius Leber. (5) Mierendorff later recalled that he was delivered by camp authorities into the hands of Communist fellow prisoners, who beat him nearly to death. (6) Haubach was arrested time and time again between 1933 and 1939 and spent two years in Esterwegen concentration camp. (7)

The overwhelming majority of social-democratic resistance groups had failed to survive the first half of the 1930s. (8) Mierendorff, Leber and Leuschner were all released from concentration camps in 1937-1938. Joachim Fest argues that this reflected the self-confidence of the Hitler government. "The sharp decline in unemployment, the improving economy, and the social programs of the new regime had produced a sense of general well-being, even pride, among the working-class... The enormous self-confidence of the Nazis in their handling of labour is suggested in the release from concentration camps in 1937 and 1938 of three once popular labour leaders - Julius Leber, Carlo Mierendorff, and last acting chairman of the General German Trade Union Federation, Wilhelm Leuschner." (9)

The Kreisau Circle

In 1940 Peter Graf Yorck von Wartenburg and Helmuth von Moltke joined forces to establish the Kreisau Circle, a small group of intellectuals who were ideologically opposed to fascism. Theodor Haubach joined this group. Other people involved included Adam von Trott, Fritz-Dietlof von der Schulenburg, Wilhelm Leuschner, Julius Leber, Adolf Reichwein, Alfred Delp, Eugen Gerstenmaier, Freya von Moltke, Carlo Mierendorff, Marion Yorck von Wartenburg, Ulrich-Wilhelm Graf von Schwerin, Dietrich Bonhoffer, Harald Poelchau and Jakob Kaiser. "Rather than a group of conspirators, these men were more of a discussion group looking for an exchange of ideas on the sort of Germany would arise from the detritus of the Third Reich, which they confidently expected ultimately to fail." (10)

The group represented a broad spectrum of social, political, and economic views, they were best described as Christian and Socialist. A. J. Ryder has pointed out that the Kreisau Circle "brought together a fascinating collection of gifted men from the most diverse backgrounds: noblemen, officers, lawyers, socialists, trade unionists, churchmen." (11) Joachim Fest argues that the "strong religious leanings" of this group, together with its ability to attract "devoted but undogmatic socialists," but has been described as its "most striking characteristic." (12)

Members of the group came mainly from the young landowning aristocracy, the Foreign Office, the Civil Service, the outlawed Social Democratic Party and the Church. "There were perhaps twenty core members of the circle, and they were all relatively young men. Half were under thirty-six and only two were over fifty. The young landowning aristocrats had left-wing ideals and sympathies and created a welcome haven for leading Social Democrats who had elected to stay like the journalist-turned-politician Carlo Mierendorff, and... Julius Leber, were the political leaders of the group, and their ideas struck lively sparks off older members of the Resistance like Goerdeler." (13)

Several members were Christian Socialists who believed the religious establishment had failed Germany. Alfred Delp was highly critical of the hierarchical bureaucracy of the Catholic Church, which he said had lost sight of human beings as the subject and object of ecclesiastical life. He agreed with Adam von Trott who wrote about the Kreisau Circle: "The key to their joint efforts is the desperate attempt to rescue the core of personal human integrity. Their fundamental ambition is to restore the inalienable divine and natural right of the human individual." This was something that Delp called "God-guided humanism". (14) Haubach added that "our movement must learn to realise that ceremonial, command and firm leadership are in no way undemocratic." (15)

On 8th January, 1943, a group of conspirators, including, Theodor Haubach, Helmuth von Moltke, Fritz-Dietlof von der Schulenburg, Johannes Popitz, Ulrich Hassell, Eugen Gerstenmaier, Adam von Trott, Ludwig Beck and Carl Goerdeler met at the home of Peter Graf Yorck von Wartenburg. Hassell was uneasy with the utopianism of the of the Kreisau Circle, but believed that the "different resistance groups should not waste their strength nursing differences when they were in such extreme danger". Haubach, Wartenburg, Moltke and Hassell were all concerned by the suggestion that Goerdeler should become Chancellor if Hitler was overthrown as they feared that he could become a Alexander Kerensky type leader. (16)

Moltke and Goerdeler clashed over several different issues. According to Theodore S. Hamerow: "Goerdeler was the opposite of Moltke in temperament and outlook. Moltke, preoccupied with the moral dilemmas of power, could not deal with the practical problems of seizing and exercising it. He was overwhelmed by his own intellectuality. Goerdeler, by contrast, seemed to believe that most spiritual quandaries could be resolved through administrative expertise and managerial skill. He suffered from too much practicality. He objected to the policies more than the principles of National Socialism, to the methods more than the goals. He agreed in general that the Jews were an alien element in German national life, an element that should be isolated and removed. But there is no need for brutality or persecution. Would it not be better to try and solve the Jewish question by moderate, reasonable means?" (17)

Moltke expressed the expectation that "a great economic community would emerge from the demobilization of armed forces in Europe" and that it would be "managed by an internal European economic bureaucracy". Combined with this he hoped to see Europe divided up into self-governing territories of comparable size, which would break away from the principle of the nation-state. Although their domestic constitutions would be quite different from each other, he hoped that by the encouragement of "small communities" they would assume public duties. His idea was of a European community built up from below. (18)

Moltke made great efforts to involve representatives of the working class in the work of the Kreisau Circle. He therefore reached out to Theodor Haubach, Carlo Mierendorff, Wilhelm Leuschner, Julius Leber and Adolf Reichwein who had all been members of the Social Democratic Party before it was banned by Adolf Hitler. These men, as Christian Socialists, were closer to Moltke's philosophy. Mierendorff saw the "revival of Christian convictions as a means of defeating the mass mentality". (19)

On 4th December, 1943, Carlo Mierendorff was killed in an air raid on Leipzig by the Royal Air Force . According to witnesses, his final word, shouted from the burning cellar, was "Madness". (20) Hans Gisevius pointed out that this was a terrible blow to both the German Resistance and the Kreisau Circle as "with him was lost the strongest and most ardent personality among the Social Democrats." (21) Theodor Haubach, who shared Mierendorff's views, tirelessly championed them after his death. He supported the strongly Christian tone of the call to action, and affirmed its obvious democratic conclusions with great emphasis. (22)

After the failed attempt to assassinate Adolf Hitler on 20th July, 1944. the Führer ordered Heinrich Himmler and Ernst Kaltenbrunner to arrest "every last person who had dared to plot against him". Hitler laid down the procedure for killing them: "This time the criminals will be given short shrift. No military tribunals. We'll hail them before the People's Court. No long speeches from them. The court will act with lightning speed. And two hours after the sentence it will be carried out. By hanging - without mercy." (23)

Members of the Kreisau Circle, including Theodor Haubach were arrested. He was executed on 23rd January 1945. Others who were executed included Peter Graf Yorck von Wartenburg (8th August, 1944), Fritz-Dietlof von der Schulenburg (10th August, 1944), Adam von Trott (26th August, 1944), Ulrich-Wilhelm Graf von Schwerin (6th September, 1944), Wilhelm Leuschner (29th September, 1944), Adolf Reichwein (20th October, 1944), Julius Leber (5th January, 1945), Alfred Delp (2nd February, 1945) and Dietrich Bonhoffer (9th April, 1945).

Primary Sources

(1) Joachim Fest, Plotting Hitler's Death: The German Resistance to Hitler (1997)

The foreign policy ideas of these two groups also differed greatly. Beck and Goerdeler's circle still thought in terms of hegemonic power and regarded it as a matter of course that Germany would cdontinue to play a major role in Europe. The Kreisauers adopted a more radical, utopian stance on the issue as well, their ideas forcusing to varying degrees on a new brand of international relations that would do away with the "borders and soldiers" of the past. In the new age that they saw dawning, selfish nationalisms would yield to a pan-European unity. The germ of this idea came from Moltke and the socialist members of the circle - Haubach, Reichwein, and Mierendorff - but it was swiftly embraced by all the others.

(2) Anton Gill, An Honourable Defeat: A History of German Resistance to Hitler (1994)

The name the Gestapo gave it (the Kreisau Circle) is misleading, for it gives the impression of an organised, coherent group, with definite aims. This is not true. The circle, which met formally at Kreisau only three times, was a large, loosely knit group of people who came mainly from the young landowning aristocracy, the Foreign Office, the Civil Service, the old Social Democratic Party and the Church. Its membership shifted and changed, and for a long time its leaders were averse to taking action of any kind against Hitler, preferring instead to let him run his course - a matter which they considered inevitable - while in the meantime they discussed what sort of Germany they would rebuild after his equally inevitable fall...

There were perhaps twenty core members of the circle, and they were all relatively young men. Half were under thirty-six and only two were over fifty. The young landowning aristocrats had left-wing ideals and sympathies and created a welcome haven for leading Social Democrats who had elected to stay like the journalist-turned-politician Carlo Mierendorff, and... Julius Leber, were the political leaders of the group, and their ideas struck lively sparks off older members of the Resistance like Goerdeler.

Student Activities

Adolf Hitler's Early Life (Answer Commentary)

The Hitler Youth (Answer Commentary)

German League of Girls (Answer Commentary)

The Political Development of Sophie Scholl (Answer Commentary)

The White Rose Anti-Nazi Group (Answer Commentary)

Kristallnacht (Answer Commentary)

Heinrich Himmler and the SS (Answer Commentary)

Trade Unions in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler v John Heartfield (Answer Commentary)

Hitler's Volkswagen (The People's Car) (Answer Commentary)

Women in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)