Samuel Cummings

Samuel George Cummings was born in Philadelphia on 4th February 1927. (1) His parents were so wealthy they had never worked. The family lost everything in the Great Depression. "His father died when Cummings was 8 from the stress of having to do actual labour for the first time in his life." However, his mother became a successful property developer and was able to afford to send her son to some of D.C.'s better private schools. (2)

Cummings served in the US Army in the later stages of the Second World War. He studied at George Washington University and Oxford University before joining the Central Intelligence Agency in December 1950. (3)

In an interview he gave to the New York Times in 1967 Cummings claimed he only worked for the CIA for a short time during the Korean War because he soon became bored as his main task was to identity the design of North Korean weapons from photographs. (4)

However, a recently released CIA Memorandum (March, 2025) shows this was untrue. It states that Cummings was initially assigned to Ground Branch, Weapons and Equipment Division, OSI. In January 1952 he was transferred to the Office of Procurement and Supply. During 1952/1953 he travelled abroad extensively, buying foreign weapons. (5) Mark Hemingway has argued it was the then deputy director of the CIA, Allen Dulles, who sent him to Europe with an unlimited budget to buy as many surplus Second World War arms as he could obtain. (6)

Samuel Cummings in Guatemala

In November 1953, he became a CIA agent in Guatemala where he was responsible for supplying arms to those trying to overthrow President Jacobo Arbenz, who had won the democratic election in 1951, with 65% of the votes cast. The CIA became concerned when Arbenz announced a new Agrarian Reform program. He said that the country needed "an agrarian reform which puts an end to the latifundios and the semi-feudal practices, giving the land to thousands of peasants, raising their purchasing power and creating a great internal market favorable to the development of domestic industry." (7)

The main opponent to Arbenz's reforms were the United Fruit Company. The company owned 550,000 acres on the Atlantic coast, 85% of which was not cultivated. Sam Zemurray, the president of the United Fruit Company, hired the political lobbyist Tommy Corcoran to express his fears to senior political figures in Washington. This included a meeting with Allen Dulles, the deputy director of the CIA. Dulles, who represented United Fruit in the 1930s, was far more interested in Corcoran’s ideas of bringing down Arbenz's government. (8)

The plan to overthrow Arbenz was called Operation Success. Allen Dulles became the executive agent and arranged for Tracey Barnes and Richard Bissell to plan and execute the operation. Barnes brought in David Atlee Phillips to run a “black” propaganda radio station. Others involved included E. Howard Hunt as chief of political action. Rip Robertson took charge of the paramilitary side of the operation who brought in David Morales and Henry Hecksher. Arbenz was forced to resign on 27th June 1954. (9)

According to the CIA: "Cables during this period (1954) state that Cummings was then buying arms for CIA and that the arms were intended for resistance elements behind the Iron Curtain." (10) Tim Weiner, writing the New York Times, argued that with the Cold War at its peak "Cummings was the agency's most cunning arms dealer. Masquerading as a Hollywood producer buying guns for the movies, he snapped up $100 million worth of surplus German arms on the cheap in Europe and shipped them to Chinese Nationalist forces in Taiwan." (11)

International Armament Corporation and Interarmco

In the recently declassified memorandum the CIA admitted that on "17 August 1954 Cummings became the principal agent of the CIA-owned companies known as International Armament Corporation and Interarmco, both incorporated in Canada, Switzerland and the US. Cummings engaged in sharp practises in his conduct of business and was also difficult to control." The CIA became concerned when they heard that in 1957 Cummings was supplying information to the FBI because they feared that his weapon deals would be brought to the attention of other Government agencies. (12)

A report in the New York Times suggested that Cummings had already left the CIA and was working for the small "Western Arms Corporation of Los Angeles, which caters to sportsmen and collectors, on their European and South American arms buyer at a salary of £5,600 a year and one eighth of 1 per cent... Within two years he had saved $25,000 and was ready to go into business for himself. (13)

However, according to the CIA memorandum it was not until early 1958 Cummings assumed sole ownership of International Armament Corporation and Interarmco. "An Agency audit established the net worth of these companies as $219,000,000. Cummings bought them with a non-interest bearing promissory note in the amount of $100,000, payable in four annual instalments of $25,000, and certain items of inventory which had a cost value of $67,000 and a market value of $250,000. These items were to remain the property of the CIA, and their cost was to be returned to the Agency after they were sold." (14)

According to Mark Hemingway: "At first Cummings worked out of his modest house in Georgetown. Cummings composed a letter announcing he was interested in purchasing arms and fired it off to dozens of heads of state and military officials. The first few months were disconcertingly quiet, until a letter from a colonel in the national guard of Panama arrived. The country had a relatively small weapons surplus it was looking to get rid of.... He made $20,000 on the deal even after the considerable shipping costs. That provided enough seed capital to cover travel expenses, and Cummings was off to the races. Like a lot of wildly successful ventures, the growth of Interarms was about 50 percent luck and 50 percent grit. Cummings traveled so much for the rest of the decade that he calculated he'd spent six months' worth of hours on planes." (15)

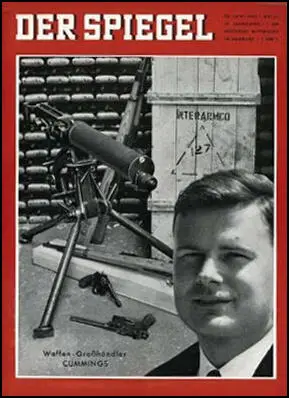

The CIA had little difficulty controlling the American media but became concerned when on 28th June 1961 the West German publication Der Spiegel reported that Cummings had been employed by CIA as an arms expert during the Korean War and that he had cooperated with CIA in "supplying arms to various trouble spots". On 4th January 1962 the Italian periodical Vie Nuove stated that Cummings was working for the CIA. As the journal was being funded by the Italian Communist Party it was feared that this information had come from the KGB. (16)

AM/WORLD

It has also been argued that in 1963 Samuel Cummings and his friend, Garry Underhill, became involved in the AM/WORLD project. (17) The first AM/WORLD document that has been released was a five-page memo prepared on 28th June, 1963. It was sent by Joseph Caldwell King, Chief of the CIA's Western Hemisphere Division. "This will serve to alert you to the inception of AM/WORLD, a new CIA program targeted against Cuba. Some manifestations of activity resulting from this program may come to your notice before long... The Kennedy Administration, it should be emphasized, is willing to accept the risks involved in utilizing autonomous Cuban exile groups and individuals who are not necessarily responsive to CIA guidance and to face up to the consequences which are unavoidable in lowering professional standards adhered to by autonomous groups (as compared with fully controlled and disciplined agent assets) is bound to entail." (18)

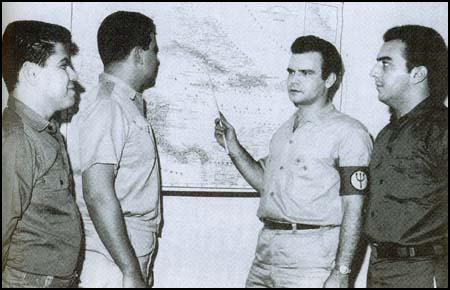

The AM/WORLD memo (104-10315-10004) was declassified on 27th January, 1999. The head of AM/WORLD was Henry Hecksher. The ranking exile under Manuel Artime was Rafael 'Chi Chi' Quintero who worked closely with CIA paramilitary officer, Carl E. Jenkins was military advisor to the AM/WORLD project. David Atlee Phillips was designated to organize safe houses and related activities for AM/WORLD. Other CIA officers who attended AM/WORLD and AM/TRUCK (an effort to produce an internal revolution against Castro in Cuba) meetings, included Ted Shackley and David Sanchez Morales. (19)

Larry Hancock and Stuart Wexler pointed out Shadow Warfare: The History of America's Undeclared Wars (2014) that over $326,000 from the AM/WORLD project was spent with Cummings' company Interarmco. "That was for everything from rifles to cannons. AM/WORLD personnel actually travelled to Europe to facilitate issues and make changes in orders for weapons not in stock with Interarmco. Cut out firms were established in Panama and Costa Rica. In Costa Rica the project used an airfield which was already being used for smuggling." (20)

John F. Kennedy Assassination

Samuel Cummings was accused of being involved in the assassination of John F. Kennedy as a consequence of being a friend of Garry Underhill. The day after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, Gary Underhill left Washington in a hurry. Late in the evening he showed up at the homes of friends in New Jersey, Robert and Charlene Fitzsimmons. He told Charlene: "I couldn't believe they'd got away with it, but they did. They tried it in Cuba, but they couldn't get away with it. After the Bay of Pigs. But Kennedy wouldn't let them get away with it. He was about to blow the whistle on them…The country is too dangerous for me now. They've gone mad. They're drug runners and gun runners. They get the intelligence and come back and tell the government how to run the country. And they're lying. And those idiots are listening to it. Kennedy gave them some time after the Bay of Pigs. ‘We'll give them a chance to save face,' he said. The CIA is under enough pressure already." (21)

Underhill told his friends that he had become aware of this "clique" was involved in selling weapons. (22) He told Charlene Fitsimmons: "This country is too dangerous for me. I've got to get on a boat. Oswald is a patsy. They set him up. It's too much. The bastards have done something outrageous. They've killed the president! I've been listening and hearing things. I couldn't believe they'd get away with it, but they did. They've gone mad! They're a bunch of drug runners and gun runners - a real violence group.I know who they are. That's the problem. They know I know. That's why I'm here.'' (23)

The journalist, Asher Brynes visited Gary Underhill on 8th May 1964. His apartment door was unlocked, he was found in bed dead from a single shot behind his left ear. The weapon used was one of his own pistols. (24) In addition to the wound behind the left-ear, the pistol was found under the left side of his body. Brynes felt this to be suspicious as Underhill was right-handed. The police investigation was minimal and the coroner reported the death as a suicide. (25)

In February 1967, Jim Garrison asked the journalist, William W. Turner, for help into his investigation into the assassination of John F. Kennedy. (26) Turner agreed and later that year he published a long article about the investigation in the Ramparts Magazine (June 1967). It included a passage on the death of Underhill. "Although the friends had always known Underhill to be perfectly rational and objective, they at first didn't take his account seriously. Robert Fitsimmons said "we couldn't believe that the CIA could contain a corrupt element every but as a ruthless – and more efficient – as the mafia." In the article Turner suggested that Cummings could have been one of the CIA officers involved in the plot to kill Kennedy. (27)

World's Largest Private Arms Dealer

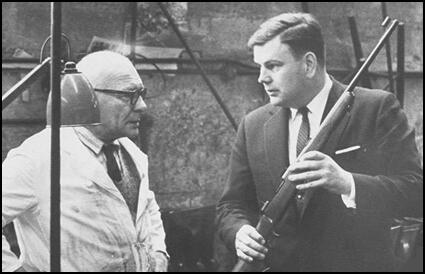

The New York Times published an interview with Cummings on 21st July, 1967 (just two days after the CIA memorandum on Cummings). "Mr Cummings is the founder, owner and president of the International Armaments Corporation, which has 17 affiliates and subsidiaries in non-Communist countries. He is a portly, well-dressed man with a boyish face that continually breaks into a smile as he describes the ironies of the arms trade. His sense of honour is keen but somewhat macabre. His gregariousness is contagious and is remarkably candid about his work. Mr Cummings observes the legalities scrupulously and makes no sales that are not approved in advance by the British or American governments, or both in instances of political sensitivity." Cummings added "It would be stupid for us to violate the law. There's very little money in smuggling. The profits are in the legal sales." (28)

Cummings boasted to Michael Isikoff that: "At one point, we had 700,000 rifles, machine guns, pistols and submachine guns stored in our warehouses in Alexandria. That was in 1968 when the gates slammed shut. At that moment, we could have instantly overwhelmed the American armed forces. We could have armed 700,000 mercenaries that could have goose-stepped right over the Memorial Bridge and even taken over The Washington Post. We also had 150 pieces of artillery, ranging from 25 mm to 150 mm... So, if I didn't like a particular piece of legislation in the Congress, I could have phoned up the speaker and I could have said, My armies will be rolling over to the Capitol, if you don't do something about that." (29)

As Victor Marchetti and John D. Marks have pointed out in The CIA and the Cult of Intelligence (1974), a book that the CIA heavily censored, that Cummings was not really being "candid about his work". They argued that the CIA used "private arms dealers" to provide weapons and other military equipment for their illegal overseas operation."The largest such dealer in the United States is the International Armaments Corporation, or Interarmco, which has its main office and some warehouses on the waterfront in Alexandria, Virginia. Advertising that it specializes in arms for law-enforcement agencies, the corporation has outlets in Manchester in England, Monte Carlo, Singapore, Pretoria, South Africa, and in several Latin American cities. Interarmco was founded in 1953 by Samuel Cummings, a CIA officer during the Korean war. The circumstances surrounding Interarmco's earlier years are murky, but CIA funds and support undoubtedly were available to it at the beginning. Although Interarmco is now a truly private corporation, it still maintains close ties with the agency. And while the CIA will on occasion buy arms for specific operations, it generally prefers to stockpile military material in advance. For this reason, it maintains several storage facilities in the United States and abroad for untraceable or ‘sterile' weapons, which are always available for immediate use. Interarmco and similar dealers are the CIA's second most important source, after the pentagon, of military material for paramilitary activities." (30)

It has been suggested that Cummings was the largest private arms dealer in the world. Tim Weiner claims: Mr. Cummings dealt with almost anybody, drawing the line only at Muammar el-Qaddafi of Libya and Idi Amin of Uganda. He sold Communist Chinese rifles to flag-waving American sportsmen. He sold weapons to the right-wing Cuban dictator Fulgencio Batista and his left-wing successor, Fidel Castro. He made millions from the apartheid regime in South Africa; from the United States, Britain, Austria, France, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, Israel, and many other nations across the Middle East and Latin America. He owned the United States franchise for Walther pistols, the handgun favored by Ian Fleming's fictional secret agent, James Bond. He made a fortune by foreseeing passage of the 1968 Gun Control Act, which banned imports of military weapons into the United States. Months before it became law, he went on a global shopping spree, stockpiling 700,000 weapons in his huge warehouse on the banks of the Potomac River in Virginia, a few miles from the Pentagon." (31)

Cummings became a tax exile and purchased a fourteen-room apartment in Monte Carlo. In a favourable article by Jacqui Shine, she stated "In this age of perpetual wars run by opaque multinational military contractors - Blackwater, Cerberus, General Dynamics - Sam Cummings may have been the last honest mercenary in the business." Shine claims Cummings led "a blameless and uneventful life" and goes on to quote Cummings as "He who harms no one, fears no one." (32)

Iran-Contra Scandal

Samuel Cummings was back in the news in 1986 as a result of the Iran Contra Scandal. In November 1979, after Iranian students stormed the U.S. embassy in Tehran and took 52 Americans hostage, President Jimmy Carter imposed an arms embargo on Iran. In September 1980, Iraq invaded Iran and Iran desperately needed weapons and spare parts for its current weapons. President Ronald Reagan officially went along with this policy and in the spring of 1983 the U.S. launched Operation Staunch, a wide-ranging diplomatic effort to persuade other nations all over the world not to sell arms or spare parts for weapons to Iran. (33)

On the 4th December, 1985, Oliver North, a military aide to the US National Security Council (NSC), proposed a new plan for selling arms to Iran. Instead of selling arms through Israel, the sale was to be direct at a markup; and a portion of the proceeds would go to the Contras, Nicaraguan paramilitary fighters waging guerrilla warfare against the Sandinista government. North now began persuading people to fund the Contras. This included $10 million from the Sultan of Brunei. (34)

In October, 1985, Congress agreed to vote 27 million dollars in non-lethal aid for the Contras in Nicaragua. However, members of the Ronald Reagan administration decided to use this money to provide weapons to the Contras and the Mujahideen in Afghanistan. Samuel Cummings was suspected of being involved in the providing military equipment to the Contras. (35) This was never proved though we do know that some of his CIA contacts played an important role in this operation. This included Ted Shackley, Carl E. Jenkins, Edwin Wilson, Richard Secord and Thomas G. Clines. (36)

Gene Wheaton was recruited to use National Air to transport these weapons. He agreed but began to have second thoughts when he discovered that it was an illegal operation and in May 1986 Wheaton told William Casey, director of the CIA, about what he knew about what later became known as Irangate. "I had no objection to the covert end of it, as long as it was legal. It wasn't.... I talked myself out of the inner circle but I was in it long enough to get to know the players and their method of operation." (37)

Wheaton told Paul Hoven, a veteran of the Vietnam War, about the operation. Hoven arranged for Wheaton to meet with Daniel Sheehan, a left-wing lawyer. Wheaton told him that some CIA officers Tom Clines and Ted Shackley had been running a top-secret assassination unit since the early 1960s. According to Wheaton, it had begun with an assassination training program for Cuban exiles and the original target had been Fidel Castro. These assassins included Rafael Quintero and Felix Rodriguez. (38)

On 5th October, 1986, a Sandinista patrol in Nicaragua shot down a C-123K cargo plane that was supplying the Contras. Wallace Blaine Sawyer Jr. and William J. Cooper were killed but Eugene Hasenfus, an Air America veteran, survived the crash and told his captors that he thought the CIA was behind the operation. He also provided information on two Cuban-Americans running the operation in El Savador. (39)

On the 9th October 1986, I. W. Stephenson, a former pilot and long-time family friend, said Eugene had told him "he worked in Southeast Asia for Air America, a company owned by the Central Intelligence Agency. He added that "he had been a loadmaster on supply planes, loading the aircraft, balancing the freight properly and sometimes seeing it to its airdrop. Stephenson recalled Hasenfus as saying he was making ''more money than the law allows.'' (40)

At a press conference on 10th October in Nicaragua, Eugene Hasenfus claimed "Two Cuban naturalized Americans that work for the C.I.A. did most of the coordination for the flights and oversaw all of our housing, transportation, also refueling and some flight plans.'' According to the The New York Times "Hasenfus then named the two reported C.I.A. officials and gave the most detailed account so far of rebel supply operations out of El Salvador and Honduras." (41)

On 12th December, 1986, Daniel Sheehan submitted to the court an affidavit detailing the Irangate scandal. He also claimed that Thomas Clines and Ted Shackley were running a private assassination program that had evolved from projects they ran while working for the CIA. Others named as being part of this assassination team included Rafael Quintero, Richard Secord, Felix Rodriguez and Albert Hakim. It later emerged that Gene Wheaton and Carl E. Jenkins were the two main sources for the Secord-Clines affidavit. (42)

The next day Donald P. Gregg, National Security adviser and a former employee of the Central Intelligence Agency, responded to Sheehan's affidavit. "Mr. Gregg's friendship with the protege, Felix Rodriguez, which dates to 1970, and his own long service in the C.I.A. have fostered wide speculation that he, and possibly Mr. Bush, were among the Reagan Administration's links to a clandestine arms-supply network. But Mr. Gregg insisted today, in the only interview he has given since the existence of the arms-supply network became known, that neither he nor Mr. Bush had any links with the network beyond knowing Mr. Rodriguez and that they had known nothing of the diversion to the rebels of some profits from arms sales to Iran... At that time, Mr. Gregg continued, his boss was the C.I.A. station chief in Saigon, Theodore G. Shackley. Now retired from the agency, Mr. Shackley played a key early role in setting up arms transfers to Iran, but Mr. Gregg said he had not maintained close contact with Mr. Shackley, seeing him only occasionally at weddings and other such events... Mr. Gregg also denied knowing several key figures in the arms-supply network - Rafael Quintero and Luis Posada Carriles, two other Bay of Pigs veterans who have worked for the C.I.A., and retired Maj. Gen. Richard V. Secord, one of the organizers of the network. (43)

President Ronald Reagan told the country that "We did not - repeat, did not - trade weapons or anything else for hostages, nor will we." However, he responded to this information by setting up a three-man committee to look into the accusations being made about the CIA. The three men chosen was John Tower, Edmund Muskie and Brent Scowcroft. The New York Times responded by arguing: "Against news of a startling plunge in his popularity, President Reagan has gone from blaming the press for the Iran arms scandal finally to some constructive steps to end it" (44)

As Samuel Cummings was the world largest private arms dealer with links to the CIA, several newspapers began to speculate that he was involved in this scandal. Michael Isikoff reported in The Washington Post: "The Iranian arms scandal recently thrust Cummings into the public spotlight, mainly because, unlike almost everybody else in his line of work, Cummings likes to talk about his business. Journalists have flocked to his Alexandria headquarters, on the corner of Prince and Union streets, seeking guidance into the byzantine and often mysterious ways of the gun trade." (45)

However, in several interviews he denied being involved in the deal. He told Elaine Sciolino: In a purely commercial sense, it was sloppily handled. We could have done it without all the commissions and middlemen. Unfortunately, the United States is using a lot of characters who charge too much and have rather baroque histories." Sciolino asked if the fact that John Tower, the head of the investigation, was his brother-in-law, would be a factor, he replied: '"I go out of my way not to talk to him. I don't want to cause him any embarrassment." (46)

The report published by the Tower Commission was delivered to President Ronald Reagan on 26th February 1987. The commission had interviewed 80 witnesses to the scheme, including Reagan. The 200-page report determined that President Reagan did not have knowledge of the extent of the program, especially about the diversion of funds to the Contras. Reagan issued a statement stating: "A few months ago I told the American people I did not trade arms for hostages. My heart and my best intentions still tell me that's true, but the facts and the evidence tell me it is not. As the Tower board reported, what began as a strategic opening to Iran deteriorated, in its implementation, into trading arms for hostages. This runs counter to my own beliefs, to administration policy, and to the original strategy we had in mind." (47)

Final Years

After the Iran-Contra Scandal Cummings went into semi-retirement. ''The arms business,'' he told an interviewer in 1989, ''is based on human folly, and folly has yet to be measured nor its depths plumbed.'' He maintained his headquarters in Virginia, which he visited less frequently in recent years, living mainly in his Monaco home. Cummings also bought a lavish estate in the hunt country west of Washington, Ashland Farms, which was used primarily by his daughters, Diana and Susan Cummings. (48)

Samuel Cummings, aged 71, died on 29th April, 1998, in Monaco after a series of strokes.

Primary Sources

(1) CIA Memorandum (19th July, 1967)

On the basis of the foregoing an inquiry was made of director, Domestic Contact Service, whose office provided the attached reply.

The following information about Samuel George Cummings 201-178343, was compiled from his 201 file and from information provided by the Office of Security and by C/CI/SPG.

(a) His date and place of birth are 4 February 1927, Philadelphia.

(b) He entered on duty with CIA as a staff employee in December 1950. He was than a GS-9 assigned to Ground Branch, Weapons and Equipment Division, OSI. In January 1952 he was transferred to the Office of Procurement and Supply. During 1952/1953 he travelled abroad extensively, buying foreign weapons.

(c) He married a German national and consequently resigned in November 1953, when he became a career agent in Guatemala.

(d) Cables of the 1951-52 period state that Cummings was then buying arms for CIA and that the arms were intended for resistance elements behind the Iron Curtain.

(e) On 17 August 1954 Cummings became the principal agent of the CIA-owned companies known as International Armament Corporation and Interarmco, both incorporated in Canada, Switzerland and the US. Cummings engaged in sharp practises in his conduct of business and was also difficult to control.

(f) In 1957 cable states that a businessman in Panama, an Agency source, knew Cummings to be providing information to the FBI and also knew him to be "careful about keeping the appropriate information to the FBI and also knew him to be "careful about keeping the appropriate U.S. Government agencies informed on his deals."

(g) In early 1958 Cummings assumed sole ownership of International Armament Corporation and Interarmco. An Agency audit established the net worth of these companies as $219,000,000. Cummings bought them with a non-interest bearing promissory note in the amount of $100,000, payable in four annual instalments of $25,000, and certain items of inventory which had a cost value of $67,000 and a market value of $250,000. These items were to remain the property of the CIA, and their cost was to be returned to the Agency after they were sold.

(h) On 28th June 1961 the West German publication Der Spiegal reported that Cummings had been employed by CIA as an arms expert during the Korean War and that he had cooperated with CIA in "supplying arms to various trouble spots.

(i) Shortly after Cummings left his staff position for Interarmco, contact with him was established by the WH Division (Directorate of Intelligence). This contact was taken over by C/CI/SPG in September 1954 (Cummings knows him only by alias.) This contact is still maintained. Until recently the principal purpose was to dispose of arms, and the CIA made a sizeable profit on these transactions. The current contact is not operations. It is not based on a project, and no payments are made to Cummings who volunteers information resulting from his extensive travels and high-level contacts. An operational clearance for Cummings use by the CI staff as an informant was granted in March 1958.

(j) On 4 January 1962 the Rome periodical Vie Nuove stated that Cummings was hired by CIA as an expert in arms and ballistics.

(k) In December 1962 the Office of Security recommended against his use by Domestic Contact Service as a source, and in December 1964 the CI staff advised that it had no operational interest in Subject (Comment: As was noted above, the statement is correct, because Subject's activity is not directed by the Agency. He volunteers information.)

(l) An interagency Source Register memo to ACSI dated 1 June 1965, stated that at the time there was "no record of a current operational interest in Subject".

(m) An Agency report on 24 February 1966 cited Cummings as trying to procure military equipment from Communist Bloc countries on behalf of DIA (Defence Intelligence Agency).

(n) Agency reports of February and May 1967 stated that Cummings had been in close contact with the BND (West German foreign intelligence service) for a year or more, that he had been given requirements by the BND, and that these included lists of Soviet and Bloc arms for procurement. It was also reported that he showed a BND representative a copy of a purchase order for the procurement of a Soviet T-54 tank, the order having originated with DIA. BND officials have often stated that Cummings is a CIA agent.

(2) New York Times (July 21, 1967)

At the age of 5, Samuel Cummings learned to dismantle and reassemble a souvenir World War I German machine gun. He believes that was the start of his career. In any case, this boyhood fascination and a robust entrepreneurial spirit. In an case, this boyhood fascination and a robust entrepreneurial spirit have helped make him the world's leading private arms merchant. Mr Cummings is the founder, owner and president of the International Armaments Corporation, which has 17 affiliates and subsidiaries in non-Communist countries.

He is a portly, well-dressed man with a boyish face that continually breaks into a smile as he describes the ironies of the arms trade. His sense of honour is keen but somewhat macabre. His gregariousness is contagious and is remarkably candid about his work.

Mr Cummings observes the legalities scrupulously and makes no sales that are not approved in advance by the British or American governments, or both in instances of political sensitivity.

"It would be stupid for us to violate the law," he said. "There's very little money in smuggling. The profits are in the legal sales.

For tax purposes, Mr Cummings lives in Monaco with his Swiss wife, Irma, and their children. He supervises his company's operations from a 13-room apartment and office there when he is not travelling on business as he is six to eight months of the year.

The bulk of his business consists of buying and reselling surplus small arms to sportsmen, collectors and non-Communist armies and police forces.

Mr Cummings handles about 250,000 small arms a year, about 80 per cent of the British and American business. He also arranges sales of larger items such as tanks and jet fighters, from one country to another for a commission.

Mr Cummings was born in Philadelphia on Feb 4 1927, to a Main Line family that lost its money in the stock market crash of 1929. His father died a few years later, but his mother went to work in a real-estate firm and put her son through the Episcopal Academy.

After his graduation from George Washington University, he worked for the Central Intelligence Agency for a short time during the Korean War but soon became bored. His job was to identity the design of North Korean weapons from photographs.

He then went to work for the small Western Arms Corporation of Los Angeles, which caters to sportsmen and collectors, on their European and South American arms buyer at a salary of £5,600 a year and one eighth of 1 per cent.

Within two years he had saved $25,000 and was ready to go into business for himself. His first transaction was a purchase of 7,000 surplus small arms from Panama, which he resold to his former employer for a small profit.

In 1956 he negotiated his first major deal, the sale to the former Dominican dictator, Rafael Trujillo, of $3.5 million worth of Swedish – owned Vampire jet fighters for a handsome commission.

(3) Victor Marchetti and John D. Marks, The CIA and the Cult of Intelligence (1974) page 120

Often the weapons and other military equipment for an operation such as that in the Congo are provided by a ‘private arms dealer'. The largest such dealer in the United States is the International Armaments Corporation, or Interarmco, which has its main office and some warehouses on the waterfront in Alexandria, Virginia. Advertising that it specializes in arms for law-enforcement agencies, the corporation has outlets in Manchester in England, Monte Carlo, Singapore, Pretoria, South Africa, and in several Latin American cities. Interarmco was founded in 1953 by Samuel Cummings, a CIA officer during the Korean war. The circumstances surrounding Interarmco's earlier years are murky, but CIA funds and support undoubtedly were available to it at the beginning. Although Interarmco is now a truly private corporation, it still maintains close ties with the agency. And while the CIA will on occasion buy arms for specific operations, it generally prefers to stockpile military material in advance. For this reason, it maintains several storage facilities in the United States and abroad for untraceable or ‘sterile' weapons, which are always available for immediate use. Interarmco and similar dealers are the CIA's second most important source, after the pentagon, of military material for paramilitary activities.

(4) Elaine Sciolino, The New York Times (4th December, 1986)

Operating in the shadows of the international arms market is an army of globe-trotting private entrepreneurs with contacts in high places and access to warehouses of weapons.

They include legitimate arms dealers with their own stocks, brokers who never take possession of weapons, and small-time smugglers.

The secret American arms sales to Iran and the diversion of profits to Nicaraguan rebels show how some of the arms merchants function not only as businessmen, but also as free-lance diplomats whose actions are likely to affect foreign policy.

The Iran affair, for example, has shaken long-held policies in the Middle East. Through the secret arms deals with the United States, Iran has found itself doing business with Israel, an archenemy, and financing insurgents against the Government of Nicaragua, which Iran supports. The United States, meanwhile, has been supplying arms to a country that it has accused of fomenting terrorism.

Samuel Cummings, a Philadelphia-born British citizen who got his start buying arms for the C.I.A. before he went into business on his own in 1953, said of the Iran deal:

''In a purely commercial sense, it was sloppily handled. We could have done it without all the commissions and middlemen. Unfortunately, the United States is using a lot of characters who charge too much and have rather baroque histories.''

Mr. Cummings should know. As a C.I.A. agent, he bought German World War II weapons for the Chinese Nationalists. Later, after opening his own business, known as Interarms, he supplied arms for the C.I.A.-backed coup in Guatemala in 1954.

Mr. Cummings' sister is married to John G. Tower, the former Senator who heads President Reagan's three-member commission investigating the Iran arms affair and other operations of the National Security Council staff in the White House.

Referring to the relationship with the former Texas Senator, Mr. Cummings said: ''I go out of my way not to talk to him. I don't want to cause him any embarrassment.''

(5) R. W. Apple Jr., The New York Times (13th December, 1986)

Vice President Bush's national security adviser, Donald P. Gregg, said today that neither he nor Mr. Bush knew until August that Mr. Gregg's protege, a former employee of the Central Intelligence Agency, was deeply involved in ''private'' arms shipments to the rebels in Nicaragua.

Mr. Gregg's friendship with the protege, Felix Rodriguez, which dates to 1970, and his own long service in the C.I.A. have fostered wide speculation that he, and possibly Mr. Bush, were among the Reagan Administration's links to a clandestine arms-supply network.

But Mr. Gregg insisted today, in the only interview he has given since the existence of the arms-supply network became known, that neither he nor Mr. Bush had any links with the network beyond knowing Mr. Rodriguez and that they had known nothing of the diversion to the rebels of some profits from arms sales to Iran. Ends Weeks of Silence...

At that time, Mr. Gregg continued, his boss was the C.I.A. station chief in Saigon, Theodore G. Shackley. Now retired from the agency, Mr. Shackley played a key early role in setting up arms transfers to Iran, but Mr. Gregg said he had not maintained close contact with Mr. Shackley, seeing him only occasionally at weddings and other such events, and had no knowledge of Mr. Shackley's links to the Iranians.

Mr. Gregg also denied knowing several key figures in the arms-supply network - Rafael Quintero and Luis Posada Carriles, two other Bay of Pigs veterans who have worked for the C.I.A., and retired Maj. Gen. Richard V. Secord, one of the organizers of the network.

(6) Michael Isikoff, The Washington Post (22nd December, 1986)

Interarms, an arms dealership with headquarters in Alexandria, sells an estimated $ 80 million worth of pistols, submachine guns, rifles, hand grenades and other weapons each year.

While the Reagan administration was secretly selling arms to Iran, arms trader Samuel Cummings was quietly building his own bridges to the government of the Ayatollah Khomeini.

As president of Interarms, which has headquarters in the heart of Alexandria's Old Town, Cummings says he has maintained regular contacts with Iranian military officials, who have frequently visited him seeking weapons for their war with Iraq. The Iranians' "buy orders," submitted to Interarms' offices in Manchester, England, have included TOW antitank missiles, the same weapon they were purchasing from the U.S. government through the assistance of former National Security Council aide Lt. Col. Oliver L. North.

"The Iranians contact us on an average of once a month and visit us once every 60 days," said Cummings in an interview last week. "I meet with them because I never know what might happen. . . . One day the Ayatollah Khomeini might even be a guest in the White House."

U.S. and British laws forbid arms exports to Iran, and Cummings (a Philadelphia native, a British subject, and a resident of Monte Carlo) said he has never consummated any sales. But his eagerness to keep in touch with the Iranians illustrates the business savvy and long-range outlook that have helped make Cummings the world's largest and best-known private arms merchant.

For more than 30 years, Interarms has dominated the shadowy world of global arms trading, selling an estimated $ 80 million worth of pistols, submachine guns, rifles, hand grenades and other weapons each year. The company offers sporting rifles and handguns to enthusiasts in the United States, stocking tens of thousands of them in a row of inauspicious, converted tobacco warehouses along the Alexandria waterfront. Its larger inventory of military items (about 250,000, which is enough to equip more than a half-dozen infantry divisions) are stockpiled in Manchester, England, and, marketed through a network of commissioned agents, are sold to armies around the world without regard to color, creed or political affiliation.

Over the years, Cummings, a former Central Intelligence Agency arms specialist who is the brother-in-law of former Texas senator John Tower, has supplied arms to some of the era's most notorious right-wing dictators: Somoza in Nicaragua, Batista in Cuba and Trujillo in the Dominican Republic. But these days, he says he is excited about his latest business partner, the People's Republic of China, from which he is buying 35,000 22-ATD semiautomatic sporting rifles, which are worth about $ 2.5 million. The Chinese guns are being offered to the American public in Interarms' 1987 catalogue: "Brand new to the U.S. market! . . . as elegant as any little .22-caliber semiautomatic you've ever seen," it reads.

"He's a very shrewd businessman," said Patrick Brogan, a British journalist who coauthored the 1983 book "Deadly Business: Sam Cummings, Interarms & the Arms Trade." "He always takes the long view. . . . In his view, he doesn't sell death, he sells small pieces of machinery, sort of like sewing machines."

The Iranian arms scandal recently thrust Cummings into the public spotlight, mainly because, unlike almost everybody else in his line of work, Cummings likes to talk about his business. Journalists have flocked to his Alexandria headquarters, on the corner of Prince and Union streets, seeking guidance into the byzantine and often mysterious ways of the gun trade.

"We've been absolutely inundated with the media," chuckled Cummings as he relaxed in a second-floor, walk-up office stocked with an imposing 19th-century French cannon, a Revolutionary War sword and racks of guns (Kalashnikov, Uzis and a Thompson "piano special" submachine gun used by the Chicago mob in the 1920s). "We don't hold ourselves out to be all-knowing, but I guess in the land of the blind, the one-eyed man is king."

Cummings' standard line on Iran is not unlike ones from other commentators: The arms-for-hostages deal was a botched operation run by amateurs who didn't know what they were doing. And, he says, Interarms could have handled the whole thing a lot more efficiently for a lot less money.

"It's almost a classic lesson in how not to do something," he said. "Who needs Adnan Khashoggi? Who needs the Israelis? . . . If the U.S. government wanted TOW missiles moved to Iran, I would have said, move the TOWs to Interarms' warehouse in England. I will notify the correct Iranian people -- and these are people I know a lot better than Khashoggi does -- and I would have invited them to take a look at them and inspect them.

"At that point, I would have said, 'send me the hostages, and once the plane lands, you can load it up with the TOWS and off you go' . . . And I wouldn't have charged any multimillion-dollar commissions because that would have been a service."

Cummings, an amiable, heavy-set man of 59, offered this advice in a good-humored voice that is vaguely reminiscent of the cartoon character Mr. McGoo. But it is a voice that turned more serious when he discussed what is for him a more pressing concern: a severe economic downturn in the arms market brought on by new international competition and a worldwide proliferation of surplus weaponry.

"The decade of the '80s has been the worst decade for the arms trade since World War II," he said. "The '50s and '60s were great. But in the '80s, the bottom has dropped out of the market. . . . The market has been saturated with overproduction and these arms don't become obsolescent overnight. . . . The pipleline has been filled. It's not like world peace has finally arrived."

Cummings' analysis is backed up by government figures showing that total U.S. arms exports alone have slipped from $ 23.7 billion four years ago to $ 15.6 billion last year. To be sure, most of this trade involves the sale of high-tech weaponry -- combat aircraft, missiles, radar equipment -- that is dominated by the U.S. government. (General Dynamics Corp., for example, exports its expensive F16 fighter jets through the Pentagon's Foreign Military Sales program, which is why these are known as "government-to-government" transactions.)

But Interarms, which dominates the private trade in "low-tech" weaponry, has felt the repercussions of the arms slump. Cummings estimates his business has declined 14 percent since the early 1980s. Last year, he was forced to shut down the company's Midland, Va., pistol factory, which cost 115 employes' jobs. (Another Interarms plant that makes German Walther pistols near Huntsville, Ala., is still operating.)

Another problem plaguing Interarms is the political roadblocks thrown in its way by the U.S. and other governments. Cummings has made no secret of his willingness to sell guns to just about anyone. (He has drawn the line, he says, at Libya's Gadhafi and a few other African dictators, such as Uganda's former ruler Idi Amin, whom he considers bloodthirsty.)

In recent years, Cummings has carved a growing niche in the Far East, selling arms to the Philippines (for its war against a communist-backed insurgency) as well as the armies of Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand. But many others with whom Cummings would be happy to do business are off-limits. He can't sell to private guerrilla armies (ruling out the Nicaraguan "contras" to whom he says he would sell "in a minute.") He can't sell to Iran, the biggest buyer on the world market.

And, he says he regrets, he can no longer sell to South Africa, where more than 20 years ago he once maintained an Interarms office that the U.S. government forced him to shut down. "I would sell to South Africa if I could ever get approval," he volunteered. "I think the blacks are better off in South Africa in terms of rights as opposed to theoretical liberties . . . than they are elsewhere in Africa."

But for all Cummings' complaints about such impediments, others, such as biographer Brogan, have noted his historic ingenuity in circumventing government restrictions. The classic example is the passage of the 1968 Gun Control Act, which prohibited the importation of military weapons into the United States. Anticipating the ban before it went into effect, Cummings went on a worldwide buying spree that had his Alexandria warehouses bulging with military firearms and kept his U.S. operations thriving for years afterward.

"At one point, we had 700,000 rifles, machine guns, pistols and submachine guns stored in our warehouses in Alexandria," recalled Cummings. "That was in 1968 when the gates slammed shut. At that moment, we could have instantly overwhelmed the American armed forces. We could have armed 700,000 mercenaries that could have goose-stepped right over the Memorial Bridge and even taken over The Washington Post.

"We also had 150 pieces of artillery, ranging from 25 mm to 150 mm," he added. "So, if I didn't like a particular piece of legislation in the Congress, I could have phoned up the speaker and I could have said, 'My armies will be rolling over to the Capitol, if you don't do something about that.' "

Cummings burst out laughing and said, of course, the scenario is a "fantasy." But one thing, he noted, is no fantasy: No matter how bleak the market may look today, the demand for guns will not go away.

"The military market is based on human folly -- not normal market precepts," said Cummings. "Human folly goes up and down. But it always exists -- and its depths have never been plummeted."

(7) Tim Weiner, New York Times (5th May, 1998)

Samuel Cummings, the world's biggest small-arms dealer, died on April 29 in Monaco after a series of strokes. He was 71 and had long reigned as the undisputed philosopher-king of the arms trade.

In a world marked by secrecy, deception, swindles and scams, Mr. Cummings stood out. He was open, had a reputation for honesty, and was a genial connoisseur of the profit found in political violence.

''The arms business,'' he told an interviewer in 1989, ''is based on human folly, and folly has yet to be measured nor its depths plumbed.'' His biographers limned him as a pleasant and law-abiding merchant of death.

His company, Interarms, did $100 million worth of business in a good year, and over the course of four decades it had many. It dealt guns and ammunition to dictators, despots, revolutionaries and counter-revolutionaries -- and, in one notable case, to both sides in a Central American guerrilla war.

Any government or guerrilla movement needing 30,000 automatic rifles in a hurry could dial Interarms' telephone numbers in Alexandria, Va., or Manchester, England, and take delivery in days subject to cash and certain licensing niceties.

Born of well-to-do British parents in Philadelphia in 1927, Mr. Cummings collected his first gun when he was 5 years old. He recalled finding a rusting German machine gun in the trash outside an American Legion post, tossing it in his little red wagon and dragging it home. It was, he remembered, love at first sight.

After a stint in the Army at the close of World War II, Mr. Cummings graduated from George Washington University and studied briefly at Oxford. In 1950 he began his true post-graduate education: he joined the fledgling Central Intelligence Agency, which provided him with more guns than he ever dreamed of.

For four years, with the cold war at its peak, Mr. Cummings was the agency's most cunning arms dealer. Masquerading as a Hollywood producer buying guns for the movies, he snapped up $100 million worth of surplus German arms on the cheap in Europe and shipped them to Chinese Nationalist forces in Taiwan.

Seeing the fantastic profit that could be made in such deals, he left the C.I.A. in 1953 and, at the age of 26, founded Interarms. The next year the agency mounted a coup in Guatemala and installed a right-wing colonel loyal to the United States. Mr. Cummings got the contract to arm the new Government.

Mr. Cummings did not discourage speculation that he maintained ties to the C.I.A.; for example, he named one of his subsidiaries Cummings Investment Associates, and let people draw their own conclusions.

Mr. Cummings dealt with almost anybody, drawing the line only at Muammar el-Qaddafi of Libya and Idi Amin of Uganda. He sold Communist Chinese rifles to flag-waving American sportsmen. He sold weapons to the right-wing Cuban dictator Fulgencio Batista and his left-wing successor, Fidel Castro.

He made millions from the apartheid regime in South Africa; from the United States, Britain, Austria, France, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, Israel, and many other nations across the Middle East and Latin America. He owned the United States franchise for Walther pistols, the handgun favored by Ian Fleming's fictional secret agent, James Bond.

He made a fortune by foreseeing passage of the 1968 Gun Control Act, which banned imports of military weapons into the United States. Months before it became law, he went on a global shopping spree, stockpiling 700,000 weapons in his huge warehouse on the banks of the Potomac River in Virginia, a few miles from the Pentagon.

''At that moment,'' he told an interviewer, ''we could have instantly overwhelmed the American armed forces.''

Mr. Cummings moved to Europe at that time, becoming a British subject and establishing residences at a chateau in the Swiss Alps and in the tax haven of Monte Carlo.

He maintained his headquarters in Virginia, which he visited less frequently in recent years. He also bought a lavish estate in the hunt country west of Washington, Ashland Farms, which was used primarily by his daughters, Diana and Susan Cummings. They survive him, as does his wife, Irma.

In September, Susan Cummings, 35, was charged with murder in the shooting death of her lover, Roberto Villegas, an Argentine polo player, who died of multiple gunshot wounds at Ashland Farms.

(8) Mark Hemingway, The All-American Arms Dealer (March 2021)

There are more than a few antique shops in historic Old Town Alexandria, Virginia, a short walk from my suburban neighborhood. Antiquing is normally of interest only if my mother-in-law is visiting, but some years back a friend messaged me to let me know one of the shops had something I should see. On the back wall, shunted behind a variety of well-preserved 19th century furniture, were two large Soviet propaganda paintings.

The first was a portrait of three strapping Russian sailors, wearing bandoleers across their chests, in front of the Aurora - the infamous ship that fired the first shot on the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg, launching the Russian Revolution. The second painting, of soldiers smoking in a field in Afghanistan, was less dramatic but a better and more impressionistic piece of art. Both paintings were done by well-known graduates of the Kharkov Art Institute and were fine examples of Soviet socialist realism - insofar as one can take any art movement that began under Stalin seriously. I inquired about the paintings, and all the clerk was able to tell me was that they originally came from the estate of a man named Samuel Cummings.

If you know anything about Samuel Cummings, you may suspect the two Soviet paintings were some of his more prosaic possessions. When the billionaire died in 1998, he owned, among many other things, the sword Napoleon carried at Waterloo. For years, he tried to open a museum in Alexandria to exhibit his collection of exotic and historic weaponry, though that never came to fruition.

As interesting as that sounds, Cummings' collection is in some respects less interesting than the manner in which he acquired it. For nearly 50 years, he was the largest arms dealer in the world.

In recent years, the waterfront in Old Town Alexandria along the Potomac River has been redeveloped. Some of the land was seized by eminent domain, the area turned into parks and boardwalks and otherwise made an inviting spot for tourists looking to schlep around the same streets once haunted by George Washington. But when I moved to the area a decade ago, there was also a small wooden building on the water where you could still make out a sign that said Interarms - the name of Cummings' company. The building is now gone, and it's hard to imagine that, through the 1980s, the same waterfront now littered with restaurants and boutiques was an industrial port where Cummings owned a series of converted tobacco warehouses stacked to the rafters with guns.

Cummings was born in Philadelphia in 1927 to parents so wealthy they had never worked. Soon thereafter they lost everything in the Great Depression. His father died when Cummings was 8 from the stress of having to do actual labor for the first time in his life.

When Cummings was 5, he found a World War I German machine gun abandoned outside an American Legion post. An adult helped him carry the 40-pound weapon back to his house, where the boy learned to take it apart and reassemble it, sparking a lifelong fascination with guns.

After Cummings' father died, his enterprising mother found a way to make one of her primary skills as a rich woman good taste - profitable. She convinced a local bank to let her move into a repossessed house and renovate it in exchange for a share of the sale profits. Cummings' mother proved quite adept at flipping houses this way. It eventually brought the family to D.C., where the housing market during the Depression was stronger. This unusual occupation necessitated moving the family every six months or so into a new home, but Cummings' mother was thrifty enough to put her children through some of D.C.'s better private schools.

Cummings enlisted immediately after high school, just as World War II was ending. As a teenager, he headed off to Fort Lee for basic training with his burgeoning collection of 50 guns packed into the trunk of his car. Cummings excelled in his cadet program in high school, and when he got to the Army he was so familiar with weapons and drills he was immediately made an acting corporal. He spent his hitch instructing other recruits on close-order drills and weapons handling. His 18-month service was uneventful - he never left Virginia - and in 1947 he enrolled in George Washington University on the GI Bill, earning a degree in political science and economics in just two years. While in school, Cummings pursued his hobby and supplemented his income by buying and selling guns. He even made a tidy profit after uncovering a cache of German World War II helmets in a Virginia scrapyard.

It was his time out of school during this period that proved to be the most fateful, however. Cummings headed off to Oxford for a term abroad during summer 1948. While in England, he and two friends pooled their money to buy the cheapest car they could find and toured the continent. For a young man obsessed with the military, the trip was a revelation.

Even though it had been over for years, the scale of World War II was so enormous that everywhere they went, the young men were surrounded by abandoned military equipment and fortifications. Cummings and his friends slept in bunkers, poked into arms caches, and drove around with a machine gun strapped to the roof of their car for fun. Anyone with a can of gasoline and a new battery could have driven away in one of the many vehicles abandoned on the side of the road. In the Falaise Pocket in France, six divisions of German soldiers had abandoned all of their supplies and equipment near the end of the war, never to return. European governments had resorted to gathering up mass quantities of leftover materiel and dumping it in the sea to get rid of it.

In Deadly Business: Sam Cummings, Interarms, and the Arms Trade, a 1983 biography by journalists Patrick Brogan and Albert Zarca that's long been out of print, Cummings recounts that the trip made an indelible impression. "The roads of rural England were lined with open-ended containers filled with ammunition," he said. "I couldn't get over it because they were standard-caliber small arms as well as artillery, and typical of law-abiding England, no one ever bothered with the stuff. To me it was astonishing."

After getting his undergraduate degree, Cummings' interest in guns was so consuming that he applied for jobs at the FBI, CIA, and National Rifle Association (NRA), thinking one of them might have use for a small arms expert. They all turned him down, at least initially. Cummings was working his way through law school when the CIA came calling. By then the Korean War was underway, and the agency was looking for people who could help identify the provenance of more exotic weapons that were turning up in the conflict. Cummings' old résumé was pulled out of the pile.

Unsurprisingly, Cummings proved particularly good at the work. He spent much of his time utilizing the CIA archives to enhance his already prodigious knowledge of weaponry.

Then one day a CIA report came across his desk, prepared in collaboration with U.S. military attachés in Europe, inquiring as to whether large quantities of German weapons still remained on the continent. The report concluded there was nothing noteworthy left. Cummings possessed considerable firsthand knowledge that the report was flat wrong, and he dashed off a memo saying so.

What Cummings didn't know was that the CIA had a specific reason for inquiring about surplus German arms. The agency was contemplating arming Chiang Kai-shek in Taiwan to launch a new invasion of mainland China, in the hopes that such an invasion would distract the Chinese military and alleviate some of the pressure in the Korean conflict. In order for the plan to work, however, the CIA needed a supply of arms that couldn't be readily traced back to the U.S.

Cummings soon found himself summoned to a personal meeting with the then - deputy director of the CIA, Allen Dulles. The legendary spymaster quickly sized up the young Cummings as being more capable than many of his more experienced superiors, and soon Cummings was off on a clandestine mission for the ages: Dulles sent him to Europe with an unlimited budget to buy as many surplus World War II arms as he could obtain. Along for the ride was another man, Leo Lippe, a director of photography from Hollywood. Their cover story was that they were buying props for the steady stream of war films that American studios were pumping out. The two men spent months traveling to Europe's most exotic locales, doing deals with heads of state and top military leaders.

Though the plan to arm Chiang Kai-shek was never put in motion, the trip was a smashing success, with Lippe and Cummings uncovering and obtaining massive stashes of arms from Scandinavia to Italy, some of which were completely unused.

Cummings returned to the U.S. in 1952, and the agency soon dispatched him on another mission. Costa Rica was disposing of 10,000 guns and in excess of a million rounds of ammunition. Given the volatile politics of Central America, the agency didn't want the weapons to fall into the wrong hands. Cummings arranged for the munitions to be sold to Western Arms, a California-based company.

The CIA offered Cummings a permanent position. He declined. His two missions weren't just successful for the CIA - they proved to be excellent on-the-job training in dealing arms.

In February 1953, when he was just 26 years old, Cummings founded the International Armament Corporation. Interarms, as it later came to be known, started with no tangible assets. Cummings worked out of his modest house in Georgetown, and the company address was a P.O. box. He did, however, have a valuable list of contacts. Cummings composed a letter announcing he was interested in purchasing arms and fired it off to dozens of heads of state and military officials.

(9) Jacqui Shine, The Last Honest Mercenary in the Business (28th March, 2023)

In 1949, the Luger Howard Unruh bought might have come into the country with a returning G.I. In 1959, when rival gangs in the Bronx amassed an arsenal for a bloody gunfight only narrowly averted by police, the bulk of the guns had almost certainly been brought to the United States by Samuel Cummings, the largest private arms dealer in the world.

Samuel Cummings didn't care about black hats or white hats when it came to buying from the lowest bidder and selling to the highest. Yet he still considered himself a man of principle. As an international arms dealer, he sold guns to Batista, to the Nicaraguans, to the Domincans - or tried to, anyway; sometimes shipments were canceled or, in Cuba, confiscated by Castro's men. But he had standards: later in life, he liked to remind people that he would never have worked with Muammar el-Quddafi or Idi Amin. He had declined to do business with them because of hurdles in export licensing. The principle was that he always followed the law.

Samuel Cummings founded the International Armament Corporation in 1953, when he was 26 years old. The company's motto - this was back when CEOs chose Latin phrases, rather than engineering them by focus group - was Esse Quam Videre : to be rather than to seem to be. In this age of perpetual wars run by opaque multinational military contractors - Blackwater, Cerberus, General Dynamics - Sam Cummings may have been the last honest mercenary in the business.

He did not operate in the shadows. Every shipment was accompanied by the appropriate paperwork. He did business in embassies all over Washington, though he was no partisan. "The arms business is by its nature apolitical," he told People magazine. "We like to say whoever wins, we win. We can supply the loser with new material or we can buy the captured material from the winner." Perhaps. One of the rare clients who would not sell to him was the government of Switzerland.

Like all the famous corporate titans, his life was performatively modest, fourteen-room apartment in Monte Carlo notwithstanding; Cummings hawk-eyed his airline miles statements, wore his Sears suits to bare threads, swam laps in the ocean every day. Even that Monte Carlo apartment was in its way a measure of his frugality: the small country has long been a notorious tax haven; outfitted with top-of-the-line office equipment, he worked from home, where he was his own secretary. Mrs. Cummings did all of the housework and cooking herself. It was, somehow, as one biographer put it, "a blameless and uneventful life."

And like many of the corporate titans, his story began with hard luck. The family's fortunes were decimated during the Great Depression, and his father died when he was eight. He was raised by a single woman who white-knuckled her children back into the upper echelon the same way so many people sought to do after the global financial crisis in 2008: she flipped houses. She and the children moved into a series of dilapidated houses, renovating them and putting them up for sale. Her success in the real estate game is how she paid for Sam to attend the prep school whose motto he later swiped for Interarmco: to be, rather than to seem to be...

Regardless, his skills were suddenly of great interest to the CIA. Allan Dulles himself sent Cummings to Europe to buy up surplus weapons with which the U.S. could covertly arm the recently deposed Chinese nationalist Chiang Kai-shek. Cummings was the one who'd told Dulles, against the received intelligence, they were there in the first place: he'd seen piles of abandoned weapons when he'd toured Western Europe with his friends. Under the guise of buying props for Hollywood movie studios, he went back and bought hundreds of thousands of guns from dealers all over Britain and the Continent. Only the Swiss refused to buy the ruse and sell the arms.

He also liked to say, "He who harms no one, fears no one." When he took his last breath at that house in Monaco at the age of 71, was Samuel Cummings afraid?