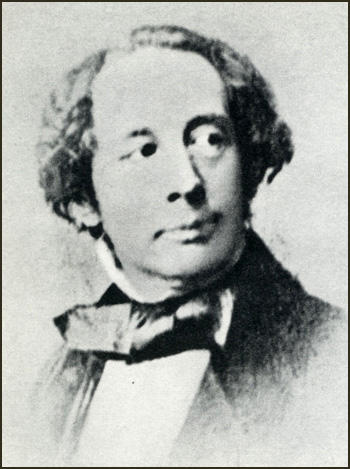

Charles Dickens (1840-1850)

In July 1840, Dickens, William Makepeace Thackeray and Daniel Maclise went to see the execution of Francois Benjamin Courvoisier, who had murdered his employer Lord William Russell. Dickens rented a room from a house that overlooked the scaffold outside Newgate Prison. Forty thousand people turned out for the hanging and over a million and a half broadsides about the murder and execution were sold (for a penny each). Although the servant from Switzerland, had confessed to the crime, Dickens had doubts about his guilt and wrote two letters to the press complaining about the behaviour of the defence lawyer.

Dickens was shocked by the behaviour of the crowd at the execution: "There was nothing but ribaldry, debauchery, levity, drunkenness and flaunting vice in fifty other shapes. I should have deemed it impossible that I could have felt any large assemblage of my fellow creatures to be so odious." After this experience Dickens campaigned against capital punishment. However, as he got older he changed his mind and wrote in favour of hanging, but argued that it should take place within the privacy of prison walls and should not provide entertainment for the masses.

Dickens was still writing The Old Curiosity Shop when he met nineteen-year-old Eleanor Picken at the home of his lawyer, Charles Smithson. Her father had died when she was a child and she had been adopted by the Smithson family. Eleanor was excited by meeting this famous writer and later described his " marvellous eyes and long hair". However, she disliked his "huge collar and vast expanse of waistcoat, and the boots with patent toes."

In September 1840 Dickens and his family took a holiday at Broadstairs. He invited the Smithsons to join him by taking a house in the town. Over the next few weeks Eleanor saw a great deal of Dickens who seemed very attracted to the young woman. During the evenings the two families played guessing games like Animal, Vegetable, Mineral and charades. They also danced together and she later commented that "at these times I confess I was horribly afraid of him" as he was guilty of the "most amusing but merciless criticisms".

One evening Dickens took Eleanor to the beach to watch the evening light fade as the tide came in. Eleanor later recalled: "Dickens seemed suddenly to be possessed with the demon of mischief; he threw his arm around me and ran me down the inclined plane to the end of the jetty till we reached a tall post. He put his other arm round this, and exclaimed in theatrical tones that he intended to hold me there till the sad sea waves should submerge us."

Eleanor Picken "implored him to let me go, and struggled hard to release myself". Dickens told her: "Don't struggle, poor little bird; you are powerless in the claws of such a kite as I." Eleanor explained: "The tide was coming up rapidly and surged over my feet. I gave a loud shriek and tried to bring him back to common sense by reminding him that my dress, my best dress, my only silk dress, would be ruined."

Eleanor called out for Catherine Dickens: "Mrs Dickens, help me, make Mr Dickens let me go - the waves are up to my knees!" Eleanor explained: "The rest of the party had now arrived, and Mrs Dickens told him not to be so silly, and not to spoil Eleanor's dress." Dickens replied: "Dress, talk not to me of dress! When the pall of night is enshrouding us... when we already stand on the brink of the great mystery, shall our thoughts be of fleshly vanities?"

Claire Tomalin, the author of Dickens: A Life (2011), has pointed out: "Clearly there was some chemistry between Eleanor and Dickens, and he must have felt that she enjoyed his attentions. She was after all the star of the evening, the chosen one, even if chosen as victim. But he was an aggressive admirer. On two occasions he rushed her under a waterfall, ruining the bonnet she was wearing each time, and he pulled her hair during games, a gesture both boyish and intimate."

After they arrived back in London Eleanor went to lunch at Dickens's home at Devonshire Terrace with the Smithsons. However, Dickens refused to leave his study and Eleanor did not see him again. Tomalin has argued: "Two things might help to explain why he turned against her. One was that she was ready to argue with him. Since his marriage he had been used to deference, while Eleanor describes herself defending Byron's verses when he criticized them, and standing up for herself generally. The other was that he may have noticed her diary keeping and objected to it. Dickens was the observer, and had no wish to be the observed."

In November 1840 Dickens was still writing The Old Curiosity Shop. He told John Forster: "You can't imagine how exhausted I am today with yesterday's labours.... All night I have been pursued by the child; and this morning I am unrefreshed and miserable. I don't know what to do with myself.... I think the close of the story will be great." He told another friend, "I am breaking my heart over this story, and cannot bear to finish it."

Later that month his friend, William Macready, lost his own three-year-old daughter to illness. He wrote in his diary: "I have lost my child. There is no comfort for that sorrow; there is endurance - that is all." Dickens now decided that Little Nell would die at the end of the story. He told Macready on 6th January 1841: "I am slowly murdering that poor child, and grow wretched over it. It wrings my heart. Yet it must be." A few days later he wrote to Daniel Maclise: "If you knew what I have been suffering in the death of that child!"

On 8th January, 1841, Dickens explained to Forster how writing about Little Nell's death was causing him a great deal of pain: "I shan't recover it for a long time. Nobody will miss her like I shall. It is such a very painful thing to me, that I really cannot express my sorrow.... I have refused several invitations for this week and next, determining to go nowhere till I had done. I am afraid of disturbing the state I have been trying to get into, and having to fetch it all back again."

After the publication of The Old Curiosity Shop, the critic, R. Shelton MacKenzie suggested that: "Little Nell, who is thought of by readers rather as a real than a fictitious personage... She is an idyllic impossibility... She is only too perfect - and her death is worthy of her life. Many a tear has been drawn forth by her imaginary adventures." Another critic writing at this time, Blanchard Jerrold, argued: "The art with which Charles Dickens managed men and women were nearly all emotional. As in all his books, he drew at will the tears of his readers... There was something feminine in the quality that led him to the right verdict, the appropriate word, the core of the heart of the question in hand... The head that governed the richly-stored heart was wise, prompt, and alert at the same time." However, Oscar Wilde remarked: "One must have a heart of stone to read the death of Little Nell without laughing." John Ruskin was also critical of Dickens in the way he manipulated emotions and argued that he "slaughtered characters as a butcher kills a lamb, to satisfy the market".

According to Peter Ackroyd, the author of Dickens (1990): "He (Dickens) gauged the extent to which pathos and comedy could be employed, and was very careful never to weary or to bore the reader. This sounds like a matter of infinite calculation, but it was not so. It was a matter of instinct; the instinct to see his own work, as it were, from the outside; to understand it as the public understood it. If he could see his characters in dumb-show in front of him, then he ensured that his readers would also see them: it is, after all, one of the things which comprise Dickens's greatness."

Some critics disapproved of the success of novelists like Dickens. Fraser's Magazine argued: "Literature has become a profession. It is a means of subsistence, almost as certain as the bar or the church. The number of aspirants increases daily, and daily the circle of readers grows wider. That there are some evils inherent in such a state of things it would be folly to deny; but still greater folly would it be to see nothing beyond these evils. Bad or good, there is no evading the great fact, now what is so firmly established. We may deplore, but we cannot alter it."

On 13th February 1841, the first episode of Dickens's next novel, Barnaby Rudge, was published in Master Humphrey's Clock. It was his first attempt at writing an historical novel. The story opens in 1775 and comes to its climax with a vivid description of the Gordon Riots. On 2nd July, 1780, Lord George Gordon, a retired navy lieutenant, who was strongly opposed to proposals for Catholic Emancipation, led a crowd of 50,000 people to the House of Commons to present a petition for the repeal of the 1778 Roman Catholic Relief Act, that had removed certain disabilities. This demonstration turned into a riot and for the next five days many Catholic chapels and private houses were destroyed. Other buildings attacked and damaged included the Bank of England, King's Bench Prison, Newgate Prison and Fleet Prison. It is estimated that over £180,000 worth of property was destroyed during the riots.

Dickens's publisher, William Hall, employed Hablot Knight Browne and George Cattermole to provide the illustrations for the serial. Browne produced about 59 illustrations, mainly of characters, whereas Cattermole's 19 drawings were usually of settings. Jane Rabb Cohen, the author of Dickens and His Principal Illustrators (1980) has argued: "At the story's climax, Dickens really let his imagination go in describing the orgiastic riots, Browne readily caught his spirit. His designs, with their tumultuous crowds yet individualized participants, fully embodied the violent excitement of the prose."

John Forster claimed that the last section of the book deserved the highest praise: "There are few things more masterly in his books. From the first low mutterings of the storm to its last terrible explosion, the frantic outbreak of popular ignorance and rage is depicted with unabated power. The aimlessness of idle mischief by which the ranks of the rioters are swelled at the beginning; the recklessness induced by the monstrous impunity allowed to the early excesses; the sudden spread of drunken guilt into every haunt of poverty, ignorance, or mischief in the wicked old city, where such rich materials of crime lie festering."

Dickens hoped that it would become as popular as the historical novels of Sir Walter Scott. The Dickens's scholar, Andrew Sanders, has pointed out: "With Barnaby Rudge Dickens laid serious claim to be the heir of the most popular novelist of the generation before his own: Sir Walter Scott. Despite the slow beginning, which establishes character, the historical situation, and the idea of mental and moral dysfunction, Dickens's narrative first flickers and then blazes with something akin to the fire with which the rioters devastate London."

The public did not like the story and sales of Master Humphrey's Clock fell dramatically after the publication of the first episode. Dickens, who was now the father of four children, had been forced to increase his spending on his family. . One of his dinner guests in April 1841 remarked that it was "rather too sumptuous a dinner for a man with a family, and only beginning to be rich". In May he was invited by his friend, Thomas Talfourd, to stand for parliament for the Reading constituency as the Liberal Party candidate. However, as he would have to pay his own expenses, he turned the offer down.

It has also been claimed during this period Dickens and Daniel Maclise visited prostitutes together. Michael Slater has claimed that along with Wilkie Collins "Dickens felt he could indulge himself in the mildly naughty badinage that was one of the epistolary games he sometimes enjoyed playing." In August 1841 Dickens went on holiday to Broadstairs and on one day while he was in Kent he visited Margate. He wrote to Maclise that: "There are conveniences of all kinds at Margate (do you take me?) and I know where they live." Claire Tomalin has suggested: "The conveniences are prostitutes, and Dickens is telling Maclise he has located them in nearby Margate. It doesn't sound like a joke. Did Dickens go out and look for the Margate prostitutes simply to find out where they were for Maclise's sake? Or because he took an interest in seeing them and talking to them, for whatever mixture of reasons? Was he thinking of using their services himself?"

On his return to London Dickens and his personal agent, John Forster, had a meeting with William Hall about the disappointing sales of Master Humphrey's Clock. It was agreed that the journal would be closed down when Barnaby Rudge came to an end. However, Dickens promised Chapman and Hall that they could publish his next novel, Martin Chuzzlewit. The terms of the agreement were very generous with Dickens being paid for each monthly instalment. He would also receive three quarters of the profit and retain half the copyright of the book.

Later that year, Dickens was taken ill suffering from an anal fistula. The operation was carried out without an anesthetic by specialist surgeon, Frederick Salmon, on 8th October. After a couple of days he had returned to work, even though he had to write standing up. He finished work on the serialized novel on 5th November and both The Old Curiosity Shop and Barnaby Rudge were published in book form on 15th December, 1841.

Dickens was extremely popular in America. The New York Herald Tribune explained why he was liked: "His mind is American - his soul is republican - his heart is democratic." Despite the high sales of his novels, Dickens did not receive any payment for his work as the country did not abide by international copyright rules. He decided to travel to America in order to put his case for copyright reform.

His publishers, Chapman and Hall, offered to help fund the trip. It was agreed they would pay him £150 a month and that when he returned they would publish the book on the visit, American Notes for General Circulation. Dickens would then receive £200 for each monthly installment. At first, Catherine refused to go to America with her husband. Dickens told his publisher, William Hall: "I can't persuade Mrs. Dickens to go, and leave the children at home; or let me go alone." According to Lillian Nayder, the author of The Other Dickens: A Life of Catherine Hogarth (2011), their friend, the actor, William Macready, persuaded her "that she owed her first duty to her husband and that she could and must leave the children behind."

Dickens and his wife left on The Britannia from Liverpool on 4th January, 1842. Their ship was a wooden paddle steamer designed for 115 passengers. The Atlantic crossing turned out to be one of the worst the ship's officers had ever known. During one storm the smokestack had to be lashed with chains to stop it being blown over and setting fire to the desks. When they approached Halifax in Nova Scotia, the ship ran aground and they had for the rising tide to release them from the rocks. Catherine Dickens wrote to her sister-in-law: "I was nearly distracted with terror and don't know what I should have done had it not been for the great kindness and composure of my dear Charles."

The ship arrived in Boston on 22nd January. James Thomas Fields was one of those who saw him arrive. In his autobiography, Yesterdays with Authors (1871) he wrote: "How well I recall the bleak winter evening in 1842 when I first saw the handsome, glowing face of the young man who was even then famous over half the globe! He came bounding into the Tremont House, fresh from the steamer that had brought him to our shores, and his cheery voice rang through the hall, as he gave a quick glance at the new scenes opening upon him in a strange land... Young, handsome, almost worshipped for his genius, belted round by such troops of friends as rarely ever man had, coming to a new country to make new conquests of fame and honor, surely it was a sight long to be remembered and never wholly to be forgotten. The splendor of his endowments and the personal interest he had won to himself called forth all the enthusiasm of old and young America, and I am glad to have been among the first to witness his arrival. You ask me what was his appearance as he ran, or rather flew, up the steps of the hotel, and sprang into the hall. He seemed all on fire with curiosity, and alive as I never saw mortal before. From top to toe every fibre of his body was unrestrained and alert."

Dickens was impressed with the city and especially liked the "elegant white wooden houses, prim, varnished churches and chapels, and handsome public buildings." Dickens also observed that there was no beggars and approved of its state-funded welfare institutions. Charles Sumner, a young radical republican, gave him a tour of the city. The two men became close friends and Dickens approved of Sumner's strong anti-slavery views. Dickens visited the Asylum for the Blind, the House of Industry for the Indigent, the School for Neglected Boys, the Reformatory for Juvenile Offenders and the House of Correction for the State, and found them models of their kind.

Dickens was introduced to the writer, Richard Dana, who described Dickens as "the cleverest man I ever met." Dickens wrote that "there never was a King or Emperor upon the Earth so cheered, and followed by crowds and waited on by public bodies and deputations of all kinds." He found it impossible to go out for his usual daily walk as people "tried to snip bits off his fur coat and asked for locks of his hair".

Many people commented on Dickens's appearance. Peter Ackroyd has argued in Dickens (1990): "They noticed his shortness, his quick and expressive eyes, the lines around his mouth, the large ears, and the odd fact that when he spoke his facial muscles slightly drew up the left side of his upper lip... as well as the long flowing hair falling on either side of his face." Lucinda Hawksley has pointed out: "Charles Dickens was renowned for his enjoyment of clothes; his love of the dramatic and his theatrical nature spilled over into his sartorial sense - and was to bemuse many of the Americans he met in 1842. The slightly garish waistcoat or flamboyant cravat, which would not have gone down well in the gentlemen's clubs in St James's (nor did it in the conventional social scene of Boston), passed as a byword for style in the artistic world in which Charles lived. He was a relatively short, slender man with an enormous personality that he chose to make the most of by dressing to reflect his dandified inner life, not simply to frame his physical features."

The writer, Washington Irving disliked the way Dickens dressed and claimed that he was "outrageously vulgar - in dress, manners and mind." One woman described him as "rather thick set, and wears entirely too much jewellery, very English in his appearance and not the best English". Another commented that he had "a dissipated looking mouth with a vulgar draw to it, a muddy olive complexion, stubby fingers... a hearty, off-hand manner, far from well-bred, and a rapid, dashing way of talking."

After leaving Boston he visited Worcester, Springfield and Hartford. At a public meeting he complained about the pirated copies of his work being distributed in the country. The local newspaper was not sympathetic to his opinions and took the view that he should be pleased and grateful with his popularity. Later he issued a statement saying that he intended to refuse to enter into any further negotiation of any kind with American publishers as long as there was no international copyright agreement. This was a decision that was to cost him dearly.

Dickens also visited Philadelphia where he met Edgar Allan Poe. Dickens also liked Cincinnati, "a very beautiful city: I think the prettiest place I have seen here, except Boston... it is well laid out; ornamented in the suburbs with pretty villas." He then moved on to New York City. On 14th February, 1842, over 3,000 people attended a dinner in his honour. He sent his friend Daniel Maclise the Bill of Fare, which included 50,000 oysters, 10,000 sandwiches, 40 hams, 50 jellied turkeys, 350 quarts of jelly and 300 quarts of ice cream. At another dinner, organised by Washington Irving, he raised once more the subject of international copyright.

Dickens wrote to John Forster on 6th March: "The institutions at Boston, and at Hartford, are most admirable. It would be very difficult indeed to improve upon them. But that is not so at New York; where there is an ill-managed lunatic asylum, a bad jail, a dismal workhouse, and a perfectly intolerable place of police-imprisonment. A man is found drunk in the streets, and is thrown into a cell below the surface of the earth... If he die (as one man did not long ago) he is half eaten by the rats in an hour's time (as this man was)."

In Washington Dickens had a meeting with President John Tyler who had recently replaced William Henry Harrison who had died in office. Dickens was unimpressed with Tyler who was known as "His Accidency". Tyler commented on Dickens's youthful appearance. Dickens thought of returning the compliment but "he looked so jaded, that it stuck in my throat". Dickens found Tyler so uninteresting he declined the invitation to dine with him at the White House. However, he did spend time with Henry Clay who he described as "a fine fellow, who has won my heart".

Dickens found the habit of spitting out gobs of chewed tobacco on the floor, common with American men, "the most sickening, beastly, and abominable custom that ever civilization saw". In a letter to Forster he described a train journey where he encountered the habit: "The flashes of saliva flew so perpetually and incessantly out of the windows all the way, that it looked as though they were ripping open feather-beds inside, and letting the wind dispose of the feathers. But this spitting is universal... There are spit-boxes in every steamboat, bar-room, public dinning-room, house of office, the place of general resort, no matter what it be.... I have twice seen gentlemen, at evening parties in New York, turn aside when they were not engaged in conversation, and spit upon the drawing-room carpet. And in every bar-room and hotel passage the stone floor looks as if it were paved with open oysters - from the quantity of this kind of deposit which tessellates it all over."

Dickens took a stagecoach in Ohio: "The coach flung us in a heap on its floor, and now crushed our heads against its roof... Still, the day was beautiful, the air delicious, and we were alone: with no tobacco spittle, or eternal prosy conversation about dollars and politics... to bore us." He also met some members of the Wyandot tribe. He thought them "a fine people, but degraded and broken down".

Dickens wrote to John Forster: "Catherine really has made a most admirable traveller in every respect. She has never screamed or expressed alarm under circumstances that would have fully justified her in doing so, even in my eyes; has never given way to despondency or fatigue, though we have now been travelling incessantly, through a very rough country... and have been at times... most thoroughly tired; has always accommodated herself, well and cheerfully, to everything; and has pleased me very much."

Dickens was disappointed by what he found in America. He told his friend, William Macready: "This is not the Republic I came to see. This is not the Republic of my imagination. I infinitely prefer a liberal Monarchy... to such a Government as this. In every respect but that of National Education, the country disappoints me. The more I think of its youth and strength, the poorer and more trifling in a thousand respects, it appears in my eyes." He wrote to Forster complaining: "I don't like the country. I would not live here, on any consideration. It goes against the grain with me. It would with you. I think it impossible, utterly impossible, for any Englishman to live here, and be happy."

At the end of March they visited Niagara Falls. Dickens commented: "It would be hard for a man to stand nearer to God than he does there." He was less impressed with Toronto where he disapproved of "its wild and rabid Toryism". He also spent time in Montreal and Quebec before travelling back to New York City where he got to the boat to Liverpool.

Dickens arrived back in London on 29th June, 1842. Soon afterwards his fifteen-year-old, sister-in-law, Georgina Hogarth, joined them at 1 Devonshire Terrace. As Michael Slater has pointed out: "Georgina went to live with them and began making herself useful to her sister in running the household and coping with the busy social life that centred on Catherine's celebrated husband. She helped especially with the ever increasing number of children, and taught the younger boys to read before they went to school. She deputized for her sister on social occasions when Catherine was unwell and looked after the family during Catherine's pregnancies. Dickens came increasingly to value Georgina's companionship (she was one of the few people who could keep pace with him on his long daily walks). He admired her intelligence and enjoyed her gift for mimicry." Charles also recorded that he thought Georgina was "one of the most amiable and affectionate of girls."

American Notes for General Circulation was published by Chapman and Hall on 19th October, 1842. Thomas Babington Macaulay, who considered Dickens a genius, refused to review it for The Edinburgh Review, because "I cannot praise it... What is meant to be easy and sprightly is vulgar and flippant... what is meant to be fine is a great deal too fine for me, as in the description of the fall of Niagara." The book received mixed reviews but sold fairly well and made Dickens £1,000 in royalties.

The book was heavily criticised by the American critics. The New York Herald Tribune called the book the work of "the most coarse, vulgar, impudent and superficial mind" They especially disliked the chapter devoted to an attack on slavery. His friend, Edgar Allan Poe, described it as "one of the most suicidal productions, ever deliberately published by an author." In the last chapter of the book Dickens complained of the viciousness of the American press and the lack of moral sense among people who prized smartness above goodness. Despite these criticisms, the pirated copies of the book sold very well. In the two days following its publication in New York City, it is reported that over 50,000 copies were purchased. Booksellers in Philadelphia claimed that they sold 3,000 in the first 30 minutes of it becoming available.

Dickens agreed with William Hall that his next book would be Martin Chuzzlewit. Dickens suggested to his friend, John Leech should co-illustrate the book with Hablot Knight Browne. This upset Browne, who had always worked on his own. Valerie Browne Lester , the author of Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens (2004) has commented: "On listening to Dickens's synopsis of the plot, he would quickly understand that this particular book did not divide itself clearly into two forms of artistic subject matter. As he was gradually growing away from caricature and grotesquerie, he could imagine that he and Leech, illustrating similar material, would inevitably become objects of comparison." Browne pointed out that Leech had a reputation for not always delivering his work promptly.

Dickens wrote to Leech on 5th November, 1842: "I find that there are so many mechanical difficulties, complications, entanglements, and impossibilities, in the way of the project I was revolving in my mind when I wrote to you last, as to render it quite impracticable. I perceive that it could not be satisfactory to you, as giving you no fair opportunity; and that it would, in practice, be irksome and distressing to me. I am therefore compelled to relinquish the idea, and for the present to deny myself the advantage of your valuable assistance."

The first episode of Martin Chuzzlewit appeared in January, 1843. It was dedicated to his friend, Angela Burdett-Coutts. Dickens wrote that: "My main object in this story was to exhibit in a variety of aspects the commonest of all the vices; to show how selfishness propagates itself, and to what a grim giant it may grow from small beginnings." The story tells of Martin Chuzzlewit, who is being raised by his rich grandfather and namesake. Martin senior has also adopted Mary Graham, with the hope that she will look after him in the later stages of his life. This plan is damaged by Martin junior falling in love with Mary. When Martin senior discovers the couple intend to marry, he disinherits his grandson.

Martin Chuzzlewit did not have the same appeal as The Pickwick Papers, Oliver Twist, Nicholas Nickleby and The Old Curiosity Shop, which eventually reached sales of 100,000 each month. After a good start, sales fell to below 20,000. Dickens was surprised by the reaction of the public and told John Forster that he felt it to be "in a hundred points immeasurably the best of my stories". He added: "I feel my power now, more than I ever did... I have greater confidence in myself than I ever had." He went on to blame the critics ("knaves and idiots") for the poor sales. One of the problems was that the country was enduring an economic recession and people did not have the money to buy fiction.

In an attempt to improve interest in the story Dickens decided to send Martin Chuzzlewit with his friend, Mark Tapely, to America. Dickens claimed that the American portion of the book "is in no other respect a caricature than it is an exhibition, for the most part, of the ludicrous side of the American character". Aware that the book provided a highly critical view of the country, he added: "As I have never, in writing fiction, had any disposition to soften what is ridiculous or wrong at home, I hope (and believe) that the good-humoured people of the United States are not generally disposed to quarrel with me for carrying the same usage abroad."

Claire Tomalin has claimed that Dickens had another reason for setting part of the story in America: "When he came to write the American chapters of Martin Chuzzlewit, he was avenging himself on everything he disliked about the way he had been treated, and pointing out, with savage humour, what he hated about America: corrupt newspapers, violence, slavery, spitting, boastfulness and self-righteousness, obsession with business and money, greedy, graceless eating, hypocrisy about supposed equality, the crude lionizing of visitors. He mocked their newspaper editors, their learned women and their congressmen... and parodied the over-blown rhetoric of their speech and writing."

Martin Chuzzlewit's visit to America did not increase sales. A clause in his agreement with Chapman and Hall allowed the publishers to cut the payments from £200 to £150 for each installment, if sales of Martin Chuzzlewit were not enough to repay the advance he had received. Dickens was furious when he heard the news that his income was to be reduced. He told John Forster that he felt as if he had been "rubbed in the tenderest part of my eyelids with bay-salt".

In September 1843 Dickens approached Angela Burdett-Coutts about the possibility of supporting Ragged Schools. These early schools provided almost the only secular education for the very poor. Dickens had provided a small sum of money from one of these schools in London. Miss Burdett-Coutts was attracted to the idea and offered to provide public baths for them and a larger school room. She also gave her support to Lord Shaftesbury, who in 1844 formed the Ragged School Union and during the next eight years over 200 free schools for poor children were established in Britain.

Dickens, who was overdrawn at the bank, decided he would have to come up with an idea for making some money. In October 1843 he decided to produce a short book for Christmas. The book was to be called A Christmas Carol. He later recalled: "My purpose was, in a whimsical kind of masque, which the good humour of the season justified, to awaken some loving and forbearing thoughts, never out of season in a Christian land." George Cruikshank, introduced him to John Leech, who agreed to do the illustrations for the book.

Dickens told his friend, Cornelius Conway Felton, that he had composed the story in his head, weeping and laughing as he walked about "the black streets of London, fifteen and twenty miles, many a night when all the sober folks had gone to bed". Andrew Sanders has suggested that "A Christmas Carol reiterates and reinforces the moral and healthy societies, like sound family relationships, are based on mutual responsibility and mutual responsiveness."

Claire Tomalin, the author of Dickens: A Life (2011) has argued that in writing the novel Dickens can be compared to other social reformers such as Friedrich Engels and Thomas Carlyle: "Carlyle, Engels and Dickens were all fired with anger and horror at the indifference of the rich to the fate of the poor, who had almost no access to education, no care in sickness, saw their young children set to work for ruthless factory owners and could consider themselves lucky if they were only half starved."

Dickens asked Chapman and Hall to publish the book on commission, as a separate venture, and he insisted on fine, coloured binding and endpapers, and gold lettering on the front and spine; and that it should cost only five shillings. It was published in an edition of 6,000 copies on 19th December, 1843. It was sold out within a few days and because of the high cost of production Dickens only made £137 from the venture. A second edition was quickly produced. However, the publishers, Lee and Haddock, produced a pirated version that sold for only twopence. Dickens sued the company and although he won his case they declared themselves bankrupt and Dickens had to pay £700 in costs and law charges.

In America the book became his biggest seller, eventually selling over a million copies, however, because he did not have a contract with the publishers, he did not receive any royalties. Dickens had hoped to make a £1,000 from A Christmas Carol but even by the end of that year the book had earned only £726.

In 1844 Charles Dickens decided to end his relationship with Chapman and Hall. Dickens's biographer, Claire Tomalin, has pointed out: "If Dickens is to be believed, each publisher started well and then turned into a villain; but the truth is that, while they were businessmen and drove hard bargains, Dickens was often demonstrably in the wrong in his dealings with them. He realized that selling copyrights had been a mistake: he was understandably aggrieved to think that all his hard work was making them rich while he was sweating and struggling, and he began to think of publishers as men who made profits from his work and failed to reward him as they should."

Robert L. Patten, the author of Charles Dickens and his Publishers (1978) has argued: "In 1844, dissatisfied with Chapman and Hall, Dickens proposed to his printers that they become his publishers as well. Despite the firm's initial reluctance, on 1st June Dickens entered into agreements that constituted Bradbury and Evans for the ensuing eight years his publishers as well as printers, with a quarter share in all future copyrights, in exchange for a large cash advance."

In 1844 Dickens saw the nineteen-years-old Christiana Weller, a concert pianist, perform in Liverpool. He immediately fell in love with her and admitted that he "kept his eyes firmly fixed on her every movement". Dickens sent her a gift of two volumes of Lord Tennyson. Dickens told her father, Thomas Weller (1799–1884) that she stood "out alone from the whole crowd the instant I saw her, and will remain there always in my sight."

Dickens wrote to his friend, Thomas James Thompson (1812–1881) about the woman who reminded him of Mary Hogarth: "I cannot joke about Miss Weller; for she is too good; and interest in her (spiritual young creature that she is, and destined to an early death, I fear) has become a sentiment with me. Good God what a madman I should seem, if the incredible feeling I have conceived for that girl could be made plain to anyone." Dickens suggested to Thompson, who was a rich widower, that he should marry Christina. The author of Dickens: A Life (2011), pointed out: "it allowed him to remain intimate with her, if only by proxy".

June Badeni has argued: "Thomas James Thompson was born in Jamaica, the son of an Englishman, James Thompson, and his Creole mistress. His grandfather Dr Thomas Pepper Thompson had emigrated from Liverpool and had grown rich on the ownership of sugar plantations, and when his son James predeceased him Dr Thompson brought his grandson to England. At his death he left him a substantial legacy. After leaving Cambridge without taking a degree, Thomas James dabbled in politics and the arts. He was a widower in his mid-thirties."

According to Peter Ackroyd, the author of Dickens (1990): "He (Dickens) encouraged and abetted Thompson in his efforts to marry Christiana... Even at this point in his life, at the age of thirty-two, his sexual responses and energies were sublimated by, or channelled towards, that strange pattern of passivity, innocence, spiritually and death which emerges so often in his fiction and in his extant correspondence. Why else did he treat Christiana Weller as if she were one of the heroines of his novels, doomed to an early death as soon as the possibility of sexual attraction becomes evident?"

After some resistance from her family, Thomas James Thompson married Christiana Weller at St Mary's Church in Barnes on 21st October 1845. Although Dickens went to the wedding he found that his feelings of jealously so strong he turned against her. He was still convinced that she was doomed to an early death. Dickens told Thompson: "I saw an angel's message in her face that day that smote me to the heart."

Charles Dickens was a supporter of the Liberal Party and in 1845 he began to consider the idea of publishing a daily newspaper that could compete with the more conservative The Times. He contacted Joseph Paxton, who had recently become very wealthy as a result of his railway investments. Paxton agreed to invest £25,000 and Dickens' publishers, Bradbury and Evans, contributed £22,500. Dickens agreed to become editor on a salary of £2,000 a year.

The first edition of The Daily News was published on 21st January 1846. Dickens wrote: "The principles advocated in the Daily News will be principles of progress and improvement; of education, civil and religious liberty, and equal legislation." Dickens employed his great friend and fellow social reformer, Douglas Jerrold, as the newspaper's sub-editor. William Henry Wills joined the newspaper as assistant editor. Dickens put his father, John Dickens, in charge of the reporters. He also paid his father-in-law, George Hogarth, five guineas a week to write on music.

William Macready confided in his diary that John Forster told him that The Daily News would greatly injure Dickens: "Dickens was so intensely fixed on his own opinions and in his admiration of his own works (who could have believed it?) that he, Forster, was useless to him as a counsel, or for an opinion on anything touching upon them, and that, as he refused to see criticisms on himself, this partial passion would grow upon him, till it became an incurable evil."

One of the newspaper's first campaigns was against the Corn Laws that had been introduced by the Conservative Party government. When Robert Peel, the Prime Minister, told the House of Commons that he had changed his mind about the legislation, Dickens did not believe him and wrote in the editorial that he was "decidedly playing false".

The Times had a circulation of 25,000 copies and sold for sevenpence, whereas The Daily News, provided eight pages for fivepence. At first it sold 10,000 copies but soon fell to less than 4,000. Dickens told his friends that he missed writing novels and after seventeen issues he handed it over to his close friend, John Forster. The new editor had more experience of journalism and under his leadership sales increased.

Dickens was a regular visitor to the home of Angela Burdett-Coutts where they discussed ways of working together. On 26th May, 1846, Dickens sent her a fourteen-page letter concerning his plan for setting up an asylum for women and girls working the London streets as prostitutes. He began the letter by explaining that these women were living a life "dreadful in its nature and consequences, and full of affliction, misery, and despair to herself." He went on to say that he hoped it could be explained to each woman who asked for help "that she is degraded and fallen, but not lost, having this shelter; and that the means of return to happiness are now about to be put into her own hands."

Dickens went on to argue: "I do not think it would be necessary, in the first instance at all events, to build a house for the Asylum. There are many houses, either in London or in the immediate neighbourhood, that could be altered for the purpose. It would be necessary to limit the number of inmates, but I would make the reception of them as easy as possible to themselves. I would put it in the power of any Governor of a London Prison to send an unhappy creature of this kind (by her own choice of course) straight from his prison, when her term expired, to the Asylum. I would put it in the power of any penitent creature to knock at the door, and say For God's sake, take me in. But I would divide the interior into two portions; and into the first portion I would put all new-comers without exception, as a place of probation, whence they should pass, by their own good-conduct and self-denial alone, into what I may call the Society of the house."

His idea was to begin with about thirty women. "What they would be taught in the house, would be grounded in religion, most unquestionably. It must be the basis of the whole system. But it is very essential in dealing with this class of persons to have a system of training established, which, while it is steady and firm, is cheerful and hopeful. Order, punctuality, cleanliness, the whole routine of household duties - as washing, mending, cooking - the establishment itself would supply the means of teaching practically, to every one. But then I would have it understood by all - I would have it written up in every room - that they were not going through a monotonous round of occupation and self-denial which began and ended there, but which began, or was resumed, under that roof, and would end, by God's blessing, in happy homes of their own."

Angela Burdett-Coutts had already become aware of the problem of prostitution. She had seen them parading every night outside her home in Piccadilly. It had been estimated by one newspaper reporter, Henry Mayhew, that London had around 80,000 prostitutes. Mayhew argued that one group that was particularly vulnerable were young female servants. He claimed that there were about 10,000 of them out on the streets on the move between jobs. If they did not have good character references from their last employer, they would be in danger of long-term unemployment and the temptation to become prostitutes. In an article by William Rathbone Greg in the Westminster Review he wrote: "The career of these women (prostitutes) is a brief one, their downward path a marked and inevitable one; and they know this well. They are almost never rescued, escape themselves they cannot."

Burdett-Coutts's close friend, the Duke of Wellington, advised her against getting involved. As one biographer has explained: "He could not understand her enthusiasm for social reform, for popular education, for clearing slums and sewers, all these were outside his comprehension." Despite his protests, she eventually agreed to fund Dickens's proposal, which was estimated at costing around £700 a year (£50,000 in 2012 money).

In June 1846 Dickens began work on a new novel. He began writing the new story while on holiday in Switzerland. He wrote to John Forster that he found himself afflicted by "an extraordinary nervousness it would be hardly possible to describe". Although the country was beautiful he missed walking in the streets of London at the end of the day's work. At the end of July he was able to send Forster the first four chapters.

On 1st October 1846, Bradbury and Evans issued the first number of a new serial novel under the title of Dealings with the Firm of Dombey and Son, Wholesale, Retail, and for Exportation . Each part was illustrated with two engravings on steel by Hablot Knight Browne. As Martin Chuzzlewit sales had not exceeded 23,000, they only printed 25,000 copies. It was an immediate success and the entire stock was sold out in a matter of hours and they had to print another 5,000 copies straight away. Dickens informed Angela Burdett Coutts: "I hear that the Dombey has been launched with great success, and was out of print on the first night."

The story starts with the death of Fanny Dombey in childbirth. One critic has argued: "The book makes a tremendous start with the death of Mrs. Dombey in childbed in the great sombre London house near Portland Place, her husband caring only for the newborn son, the fashionable doctors powerless, and her little daughter, Florence, weeping and holding on to her... The story creates a world, draws in the reader and keeps its grip. The London he knew so well (and had missed so badly abroad) is set before us, from the grand residential streets to the northern edges of town, the modest dwellings and shops near the river in the City, and Camden Town." Dickens told John Forster: "The Dombey sale is brilliant! I had put before me thirty thousand as the limit of the most extreme success, saying that if we should reach that, I should be more than satisfied." Further reprints were necessary and Dickens told another friend that "Dombey is a prodigious success."

The baby, Paul Dombey, is sent to Brighton to be looked after by Mrs Pipchin. According to Michael Slater, "Paul's death caused a great sensation" and was "described as having plunged the British reading public into a veritable national mourning, and the publishers happily increased the serial's press run to thirty-three thousand." Dickens's wrote in his diary that in part 6 of the serial he needed "throw the interest of Paul, at once on Florence" the daughter.

During this period Dickens was earning £460 for each monthly edition. Forster reported that "his accounts for the first half-year of Dombey were so much in excess of what had been expected... that from this date all embarrassments connected with money were brought to a close."The publication of the work extended over twenty months and on its completion, in 1848, it was brought out in a single volume entitled, Dombey and Son. Dickens was now a wealthy man. However, he still complained about the profits being made by his publishers, Bradbury and Evans. Dickens remarked to Forster that: "It was a consequence of the astonishing rapidity of my success and the steady rise of my fame that the enormous profits of these books should flow into other hands than mine."

Dickens still remained interested in social reform and wrote to William Makepeace Thackeray in January 1848: "I do sometimes please myself with thinking that my success has opened the way for good writers. And of this, I am quite sure now, and hope I shall be when I die - that in all my social doings I am mindful of this honour and dignity and always try to do something towards the quiet assertion of their right place. I am always possessed with the hope of leaving the position of literary men in England, something better and more independent than I found it."

Dickens was about to begin writing David Copperfield when his eighth child was born on 16th January, 1849. He named him Henry Fielding Dickens after the novelist, Henry Fielding. He told John Forster that this was in "a kind of homage to the style of the novel he was about to write." It was to be a first-person narrative that was to draw on some of his own experiences and is considered to be the most autobiographical novel that he produced.

The novel was originally brought out under the title, The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences, and Observations of David Copperfield the Younger, of Blunderstone Rookery . The first number appeared on 1st May 1849. David Copperfield's father had died six months before his birth. His mother, Clara Copperfield, marries Edward Murdstone. He treats his stepson very badly and eventually he is sent from home to a school run by a cruel teacher, Mr Creakle.

After the death of his mother, David, aged ten, is forced to work in a warehouse owned by his step-father. He dislikes the work and the company of the other boys, he runs away and seeks help from his great-aunt, Betsy Trotwood, whom he has never seen. She agrees to adopt him and sends him to school in Canterbury. David Copperfield does very well and like Dickens, after leaving school, learns the art of stenography and finds work reporting debates in the House of Commons. Later he writes for magazines and periodicals.

David marries Dora Spenlow. Rodney Dale, the author of Dickens Dictionary (2005) has argued: "Dora, a pretty, captivating, affectionate girl, but utterly ignorant of everything practical. It is not long before David discovers that it will be altogether useless to expect that his wife will develop any stability of character, and he resolves to estimate her by the good qualities she has, and not by those which he has not. One night, she says to him in a very thoughtful manner that she wishes him to call her his child-wife."

After his wife dies, Copperfield goes to live abroad. When he returns three years later he discovers his writing has made him famous. He marries Agnes Wickfield and is now a contented man. Copperfield pays fulsome tribute to his new wife: "Clasped in my embrace, I held the source of every worthy aspiration I had ever had; the centre of myself, the circle of my life, my own, my wife; my love of whom was founded on a rock!"

Hablot Knight Browne once again did the illustrations. Valerie Browne Lester has pointed out: "If Copperfield were indeed autobiographical, Phiz was uncannily able to enter into the spirit of Dickens's real memories. He managed to capture Micawber's grandiose and improvident nature - based on Dickens's own father... Phiz seems to be literally under Dickens's skin." Dickens was very pleased with the result and not since The Pickwick Papers had he been so openly appreciative of Browne's efforts.

While writing David Copperfield Dickens continued to search for a property suitable for his home for "fallen women". Claire Tomalin, the author of Dickens: A Life (2011), has pointed out: "She (Angela Burdett-Coutts) gave him almost free rein in setting it up. He needed to find a house large enough to take up to a dozen or so young women, sharing bedrooms, plus a matron and her assistant - his early plan to take thirty was given up as impractical... In May 1847 he came upon a small, solid brick house near Shepherd's Bush, then still in the country, but well connected with central London by the Acton omnibus. The house was already named Urania Cottage but from the first he called it simply the Home, the idea that it should feel like a home rather than an institution being so important to him. He liked the fact that it stood in a country lane, with its own garden, and saw at once that the women could have their own small flowerbeds to cultivate. There was also a coach house and stables which could be made into a laundry."

The lease was agreed in June 1847 and soon afterwards Dickens started interviewing possible matrons. Miss Burdett-Coutts appointed Dr. James Kay-Shuttleworth, a Poor Law Commissioner, who had written about education and the working-class, to help Dickens with the task. However, the two men disagreed about the role of religious education in the home. Dickens told her that Kay-Shuttleworth's theorizing made him feel as if he had "just come out of the Desert of Sahara where my camel died a fortnight ago."

In October 1847, Dickens published a leaflet that he gave to prostitutes encouraging them to apply to join Urania Cottage: "If you have ever wished (I know you must have done so, sometimes) for a chance of rising out of your sad life, and having friends, a quiet home, means of being useful to yourself and others, peace of mind, self-respect, everything you have lost, pray read... attentively... I am going to offer you, not the chance but the certainty of all these blessings, if you will exert yourself to deserve them. And do not think that I write to you as if I felt myself very much above you, or wished to hurt your feelings by reminding you of the situation in which you are placed. God forbid! I mean nothing but kindness to you, and I write as if you were my sister." Dickens interviewed every young woman who responded to the leaflet or who was recommended to him by prison governors, magistrates or the police. Once accepted she would be told that no one would ever mention her past to her and that even the matrons would not be informed about it. She was advised not to talk further about her own history to anyone else.

Dickens started the home with four girls with the expectation of the arrival of two more the following week. Mrs Holdsworth had been appointed matron and Mrs Fisher as her assistant. Dickens wrote to Angela Burdett-Coutts: "I wish you could have seen them at work on the first night of this lady's engagement - with a pet canary of hers walking about the table, and the two girls deep in my account of the lesson books, and all the knowledge that was to be got out of them as we were putting them away on the shelves." According to Dickens, the first girl who entered Urania Cottage, cried with joy when she saw her bed. Dickens wrote to Miss Burdett-Coutts on 28th October, 1847: "We have now eight, and I have as much confidence in five of them, as one can have in the beginning of anything so new."

The home was officially opened in November 1847. The women slept three or four to a bedroom. They got up at six in the morning, and they had to make each other's beds, and were required to inform on anyone who was hiding alcohol. They had short prayers, twice daily. Dickens was determined to avoid preaching, heavy moralizing and calls for penitence. He told Miss Burdett-Coutts that they had to be very careful about the appointment of a chaplain: "The best man in the world could never make his way to the truth of these people, unless he were content to win it very slowly, and with the nicest perception always present to him... of what they have gone through. Wrongly addressed they are certain to deceive."

Dickens later recalled the type of women he recruited for Urania Cottage. "Among the girls were starving needlewomen, poor needlewomen who had robbed... violent girls imprisoned for committing disturbances in ill-conducted workhouses, poor girls from Ragged Schools, destitute girls who have applied at police offices for relief, young women from the streets - young women of the same class taken from the prisons after under-going punishment there as disorderly characters, or for shoplifting, or for thefts from the person: domestic servants who had been seduced, and two young women held to bail for attempting suicide."

Angela Burdett-Coutts thought that the women should wear dark clothes. She was supported by George Laval Chesterton, the governor of Coldbath Fields Prison, who argued that the "love of dress is the cause of ruin of a vast number of young women in humble circumstances". Augustus Tracey, the governor of Tothill Fields Prison, agreed saying that in twenty years' experience he had found the excessive love of dress often resulted in an "early lapse into crime - for girls it was equal as a cause of ruin as drink was for men." Dickens rejected this advice and insisted they should be given dresses in cheerful colours they would enjoy wearing. He wrote: "These people want colour... In these cast-iron and mechanical days, I think even such a garnish to the dish of their monotonous and hard lives, of unspeakable importance... I have made them as cheerful in appearance as they reasonably could be - at the same time very neat and modest. Three of them will be dressed alike, so that there are four colours of dresses in the Home at once; and those who go out together, with Mrs Holdsworth, will not attract attention, or feel themselves marked out, by being dressed alike."

Dickens also arranged for the women to be well fed, with breakfast, dinner and tea at six, being their last meal of the day. There was schooling for two hours every morning where they were taught to read and write. They took it in turns to read aloud while they did their needlework, making and mending their own clothes. The women also had plots in the garden where they could grow vegetables. Dickens also paid for his friend, John Hullah, to give singing lessons. The inmates did all the household tasks, which were rotated weekly. They also made soup that was distributed to local people on poor relief.

Jenny Hartley, the author of Charles Dickens and the House of Fallen Women (2008) has pointed out that the women were not allowed out on their own and the matron would take them out individually or in small groups. Nor were they allowed unsupervised visits or private correspondence as Dickens was afraid that old associates might try to draw them back to the life they had left behind. They were given marks for good behaviour and lose marks for bad behaviour. These marks were worth money and this would be saved for them to use when they left the house.

Angela Burdett-Coutts was concerned about the religion of the staff. She objected to Dickens employing Mrs Fisher, a Nonconformist. Dickens, who had been impressed by her "mild sweet manners" agreed to sack her, but was not happy about it: "I have no sympathy whatever with her private opinions, I have a very strong feeling indeed - which is not yours, at the same time I have no doubt whatever that she ought to have stated the fact of her being a dissenter to me, before she was engaged... With these few words and with the fullest sense of your very kind and considerate manner of making this change, I leave it."

Mrs Holdsworth left her post but Dickens was very pleased with his appointment of Georgina Morson, as matron. She was a widow of a doctor. She had three young children but her mother agreed to look after them so she could do the job. Morson provided them with good food, an orderly life, training in reading, writing, sewing, domestic work, cooking and laundering. It has been claimed that she looked after them so well that they wept when they parted from her.

Dickens expected that each of them would live at the cottage for about a year before being given a supervised place on an emigrant ship, by which time they would be well nourished, healthy, better educated and in a better state to manage their lives. Dickens hoped they would find husbands but Angela Burdett-Coutts had doubts about former prostitutes marrying. The first three young women, Julia Mosley, Jane Westaway and Martha Goldsmith, left for Australia on The Calcutta , in January 1849. It was an old, slow boat and the journey took nearly six months. They were to be met by the Reverend Augustus Short at the port of Adelaide. However, by the time that Short arrived at the dockside, the three women had disappeared. Short wrote to Dickens that he had been told by the captain that all three "had returned to their old ways and were totally unfit to be recommended as household servants." Dickens told Miss Burdett-Coutts that this news caused him "heavy disappointment and great vexation." He added: "God send we may do better with some of the others!"

In February 1849, Isabella Gordon arrived at Urania Cottage. Jenny Hartley, the author of Charles Dickens and the House of Fallen Women (2008) has pointed out: "Isabella comes across as a girl who liked to enjoy herself; she added to the gaiety of the house. This endeared her all the more to Dickens, keen as he was to foster an agreeable atmosphere... High-spirited Isabella was always the one who caught his eye. She was sparky and not at all intimidated by him... She brought colour and vivacity; she had a sense of humour and a sense of style... But she was pushing it, as Dickens eventually spotted." However, he continued to enjoy her company and wrote about my "friend Isabella Gordon".

Despite the favourable treatment she received, Isabella Gordon continued to rebel and when she insulted the matron, Georgiana Morson, in November, 1849, Dickens decided to send her away. "The girl herself, now that it had really come to this, cried, and hung down her head, and when she got out at the door, stopped and leaned against the house for a minute or two before she went to the gate - in a most miserable and wretched state. As it was impossible to relent, with any hope of doing good, we could not do so. We passed her in the lane, afterwards, going slowly away, and wiping her face with her shawl. A more forlorn and hopeless thing altogether, I never saw."

Dickens was aware that given her situation Isabella Gordon would return to a world of prostitution. A few days later he wrote that month's episode of David Copperfield, that included a passage about Martha Endell, who was returning to her life as a prostitute: "Then Martha arose, and gathering her shawl about her, covering her face with it, and weeping aloud, went slowly to the door. She stopped a moment before going out, as if she would have uttered something or turned back; but no word passed her lips. Making the same low, dreary, wretched moaning in her shawl, she went away." In the novel Martha later emigrates to Australia where she marries happily. It is unlikely that Isabella Gordon would have shared a similar fate.

Dickens also had trouble with Sesina Bollard. He described her as "the most deceitful little minx in this town - I never saw such a draggled piece of fringe upon the skirts of all that is bad... she would corrupt a Nunnery in a fortnight." Another girl, Jemima Hiscock, "forced open the door of the little beer cellar with knives and got dead drunk". He accused Jemima of using "the most horrible language" and it was thought the beer must have been, "laced with spirits from over the wall". The most disturbing incident was when the matron found a police constable "yesterday morning between four and five... in the parlour with Sarah Hyam."

Primary Sources

(1) Charles Dickens, letter to Angela Burdett-Coutts (26th May, 1846)

In reference to the Asylum, it seems to me very expedient that you should know, if possible, whether the Government would assist you to the extent of informing you from time to time into what distant parts of the World, women could be sent for marriage, with the greatest hope for future families, and with the greatest service to the existing male population, whether expatriated from England or born there. If these poor women could be sent abroad with the distinct recognition and aid of the Government, it would be a service to the effort. But I have (with reason) a doubt of all Governments in England considering such a question in the light, in which men undertaking that immense responsibility, are bound, before God, to consider it. And therefore I would suggest this appeal to you, merely as something which you owe to yourself and to the experiment; the failure of which, does not at all affect the immeasurable goodness and hopefulness of the project itself.

I do not think it would be necessary, in the first instance at all events, to build a house for the Asylum. There are many houses, either in London or in the immediate neighbourhood, that could be altered for the purpose. It would be necessary to limit the number of inmates, but I would make the reception of them as easy as possible to themselves. I would put it in the power of any Governor of a London Prison to send an unhappy creature of this kind (by her own choice of course) straight from his prison, when her term expired, to the Asylum. I would put it in the power of any penitent creature to knock at the door, and say For God's sake, take me in. But I would divide the interior into two portions; and into the first portion I would put all new-comers without exception, as a place of probation, whence they should pass, by their own good-conduct and self-denial alone, into what I may call the Society of the house. I do not know of any plan so well conceived, or so firmly grounded in a knowledge of human nature, or so judiciously addressed to it, for observance in this place, as what is called Captain Maconnochie's Mark System, which I will try, very roughly and generally, to describe to you.

A woman or girl coming to the Asylum, it is explained to her that she has come there for useful repentance and reform, and because her past way of life has been dreadful in its nature and consequences, and full of affliction, misery, and despair to herself. Never mind Society while she is at that pass. Society has used her ill and turned away from her, and she cannot be expected to take much heed of its rights or wrongs. It is destructive to herself, and there is no hope in it, or in her, as long as she pursues it. It is explained to her that she is degraded and fallen, but not lost, having this shelter; and that the means of Return to Happiness are now about to be put into her own hands, and trusted to her own keeping. That with this view, she is, instead of being placed in this probationary class for a month, or two months, or three months, or any specified time whatever, required to earn there, a certain number of Marks (they are mere scratches in a book) so that she may make her probation a very short one, or a very long one, according to her own conduct. For so much work, she has so many Marks; for a day's good conduct, so many more. For every instance of ill-temper, disrespect, bad language, any outbreak of any sort or kind, so many - a very large number in proportion to her receipts - are deducted. A perfect Debtor and Creditor account is kept between her and the Superintendent, for every day; and the state of that account, it is in her own power and nobody else's, to adjust to her advantage. It is expressly pointed out to her, that before she can be considered qualified to return to any kind of society - even to the Society of the Asylum - she must give proofs of her power of self-restraint and her sincerity, and her determination to try to shew that she deserves the confidence it is proposed to place in her. Her pride, her emulation, her sense of shame, her heart, her reason, and her interest, are all appealed to at once, and if she pass through this trial, she must (I believe it to be in the eternal nature of things) rise somewhat in her own self-respect, and give the managers a power of appeal to her, in future, which nothing else could invest them with. I would carry a modification of this Mark System through the whole establishment; for it is its great philosophy and its chief excellence that it is not a mere form or course of training adapted to the life within the house, but is a preparation - which is a much higher consideration - for the right performance of duty outside, and for the formation of habits of firmness and self-restraint. And the more these unfortunate persons were educated in their duty towards Heaven and Earth, and the more they were tried on this plan, the more they would feel that to dream of returning to Society, or of becoming Virtuous Wives, until they had earned a certain gross number of Marks required of everyone without the least exception, would be to prove that they were not worthy of restoration to the place they had lost. It is a part of this system, even to put at last, some temptation within their reach, as enabling them to go out, putting them in possession of some money, and the like; for it is clear that unless they are used to some temptation and used to resist it, within the walls, their capacity of resisting it without, cannot be considered as fairly tested.

What they would be taught in the house, would be grounded in religion, most unquestionably. It must be the basis of the whole system. But it is very essential in dealing with this class of persons to have a system of training established, which, while it is steady and firm, is cheerful and hopeful. Order, punctuality, cleanliness, the whole routine of household duties - as washing, mending, cooking - the establishment itself would supply the means of teaching practically, to every one. But then I would have it understood by all - I would have it written up in every room - that they were not going through a monotonous round of occupation and self-denial which began and ended there, but which began, or was resumed, under that roof, and would end, by God's blessing, in happy homes of their own.

I have said that I would put it in the power of Governors of Prisons to recommend Inmates. I think this most important, because such gentlemen as Mr. Chesterton of the Middlesex House of Correction, and Lieutenant Tracey of Cold Bath Fields, Bridewell, (both of whom I know very well) are well acquainted with the good that is in the bottom of the hearts, of many of these poor creatures, and with the whole history of their past lives; and frequently have deplored to me the not having any such place as the proposed establishment, to which to send them - when they are set free from Prison. It is necessary to observe that very many of these unfortunate women are constantly in and out of the Prisons, for no other fault or crime than their original one of having fallen from virtue. Policemen can take them up, almost when they choose, for being of that class, and being in the streets; and the Magistrates commit them to Jail for short terms. When they come out, they can but return to their old occupation, and so come in again. It is well-known that many of them fee the Police to remain unmolested; and being too poor to pay the fee, or dissipating the money in some other way, are taken up again, forthwith. Very many of them are good, excellent, steady characters when under restraint - even without the advantage of systematic training, which they would have in this Institution - and are tender nurses to the sick, and are as kind and gentle as the best of women.

There is no doubt that many of them would go on well for some time, and would then be seized with a violent fit of the most extraordinary passion, apparently quite motiveless, and insist on going away. There seems to be something inherent in their course of life, which engenders and awakens a sudden restlessness and recklessness which may be long suppressed, but breaks out like Madness; and which all people who have had opportunities of observation in Penitentiaries and elsewhere, must have contemplated with astonishment and pity. I would have some rule to the effect that no request to be allowed to go away would be received for at least four and twenty hours, and that in the interval the person should be kindly reasoned with, if possible, and implored to consider well what she was doing. This sudden dashing down of all the building up of months upon months, is, to my thinking, so distinctly a Disease with the persons under consideration that I would pay particular attention to it, and treat it with particular gentleness and anxiety; and I would not make one, or two, or three, or four, or six departures from the Establishment a binding reason against the readmission of that person, being again penitent, but would leave it to the Managers to decide upon the merits of the case: giving very great weight to general good conduct within the house.

(2) Charles Dickens, The Daily News (4th February, 1846)

I offer no apology for entreating the attention of the readers of the Daily News to an effort which has been making for some three years and a half, and which is making now, to introduce among the most miserable and neglected outcasts in London, some knowledge of the commonest principles of morality and religion; to commence their recognition as immortal human creatures, before the Gaol Chaplain becomes their only schoolmaster; to suggest to Society that its duty to this wretched throng, foredoomed to crime and punishment, rightfully begins at some distance from the police office, and that the careless maintenance from year to year, in this the capital city of the world, of a vast hopeless nursery of ignorance, misery, and vice: a breeding place for the hulks and jails: is horrible to contemplate.

This attempt is being made, in certain of the most obscure and squalid parts of the Metropolis; where rooms are opened, at night, for the gratuitous instruction of all comers, children or adults, under the title of Ragged Schools. The name implies the purpose. They who are too ragged, wretched, filthy, and forlorn, to enter any other place: who could gain admission into no charity school, and who would be driven from any church door; are invited to come in here, and find some people not depraved, willing to teach them something, and show them some sympathy, and stretch a hand out, which is not the iron hand of law, for their correction.

Before I describe a visit of my own to a Ragged School, and urge the readers of this letter for God's sake to visit one themselves, and think of it (which is my main object), let me say, that I know the prisons of London well. That I have visited the largest of them, more times than I could count; and that the children in them are enough to break the heart and hope of any man. I have never taken a foreigner or a stranger of any kind, to one of these establishments, but I have seen him so moved at sight of the child offenders, and so affected by the contemplation of their utter renouncement and desolation outside the prison walls, that he has been as little able to disguise his emotion, as if some great grief had suddenly burst upon him. Mr. Chesterton and Lieutenant Tracey (than whom more intelligent and humane Governors of Prisons it would be hard, if not impossible, to find) know, perfectly well, that these children pass and repass through the prisons all their lives; that they are never taught; that the first distinctions between right and wrong are, from their cradles, perfectly confounded and perverted in their minds; that they come of untaught parents, and will give birth to another untaught generation; that in exact proportion to their natural abilities, is the extent and scope of their depravity; and that there is no escape or chance for them in any ordinary revolution of human affairs. Happily, there are schools in these prisons now. If any readers doubt how ignorant the children are, let them visit those schools, and see them at their tasks, and hear how much they knew when they were sent there. If they would know the produce of this seed, let them see a class of men and boys together, at their books (as I have seen them in the House of Correction for this county of Middlesex), and mark how painfully the full grown felons toil at the very shape and form of letters, their ignorance being so confirmed and solid. The contrast of this labour in the men, with the less blunted quickness of the boys; the latent shame and sense of degradation struggling through their dull attempts at infant lessons; and the universal eagerness to learn, impress me, in this passing retrospect, more painfully than I can tell.

For the instruction, and as a first step in the reformation, of such unhappy beings, the Ragged Schools were founded. I was first attracted to the subject, and indeed was first made conscious of their existence, about two years ago, or more, by seeing an advertisement in the papers dated from West Street, Saffron Hill, stating "That a room has been opened and supported in that wretched neighbourhood for upwards of twelve months, where religious instruction had been imparted to the poor", and explaining in a few words what was meant by Ragged Schools as a generic term, including, three, four or five similar places of instruction. I wrote to the masters of this particular school to make some further enquiries, and went myself soon afterwards.

It was a hot summer night; and the air of Field Lane and Saffron Hill was not improved by such weather, nor were the people ill those streets very sober or honest company. Being unacquainted with the exact locality of the school, I was fain to make some inquiries about it. These were very jocosely received in general; but everybody knew where it was, and gave the right direction to it. The prevailing idea among the loungers (the greater part of them the very sweepings of the streets and station houses) seemed to be, that the teachers were quixotic, and the school upon the whole "a lark". But there was certainly a kind of rough respect for the intention, and (as I have said) nobody denied the school or its whereabouts, or refused assistance in directing to it.

It consisted at that time of either two or three - I forget which - miserable rooms, upstairs in a miserable house. In the best of these, the pupils in the female school were being taught to read and write; and though there were among the number, many wretched creatures steeped in degradation to the lips, they were tolerably quiet, and listened with apparent earnestness and patience to their instructors. The appearance of this room was sad and melancholy, of course - how could it be otherwise! - but, on the whole, encouraging.

The close, low, chamber at the back, in which the boys were crowded, was so foul and stifling as to be, at first, almost insupportable. But its moral aspect was so far worse than its physical, that this was soon forgotten. Huddled together on a bench about the room, and shown out by some flaring candles stuck against the walls, were a crowd of boys, varying from mere infants to young men; sellers of fruit, herbs, lucifer-matches, flints; sleepers under the dry arches of bridges; young thieves and beggars - with nothing natural to youth about them: with nothing frank, ingenuous, or pleasant in their faces; low-browed, vicious, cunning, wicked; abandoned of all help but this; speeding downward to destruction; and unutterably ignorant.