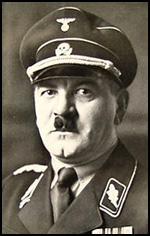

Julius Schreck

Julius Schreck was born in Munich on 13th July, 1898. He served in the German Army during the First World War. He developed right-wing views and was a member of the Freikorps. In March, 1919, Schreck took part in the overthrow of the Bavarian Socialist Republic.

In 1920 Schreck joined the National Socialist German Workers Party (NSDAP). Soon afterwards he became a close friend of Adolf Hitler. Schreck helped organize the Ordnertruppe (Steward Troop). Its task was to keep order at indoor political meetings. It later became known as the Saalschutz and became part of the larger Athletic and Sports Section of the party. Over the next couple of years its role changed and it specialized in the role of guarding speakers.

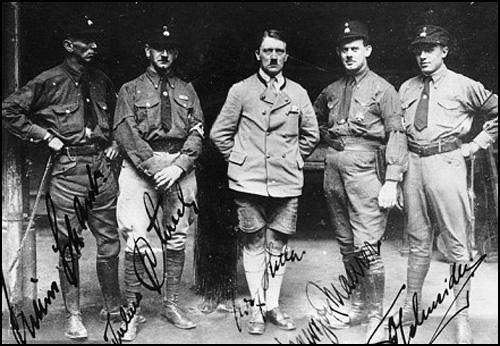

On 9th November, 1923, Adolf Hitler, Hermann Kriebel, Eric Ludendorff, Julius Steicher, Julius Schreck, Hermann Goering, Max Scheubner-Richter, Wilhelm Brückner and 3,000 armed supporters of the Nazi Party marched through Munich in an attempt to join up with Roehm's forces at the War Ministry. At Odensplatz they found the road blocked by the Munich police. What happened next is in dispute. One observer said that Hitler fired the first shot with his revolver. Another witness said it was Steicher while others claimed the police fired into the ground in front of the marchers.

William L. Shirer has argued: "At any rate a shot was fired and in the next instant a volley of shots rang out from both sides, spelling in that instant the doom of Hitler's hopes. Scheubner-Richter fell, mortally wounded. Goering went down with a serious wound in his thigh. Within sixty seconds the firing stopped, but the street was already littered with fallen bodies - sixteen Nazis and three police dead or dying, many more wounded and the rest, including Hitler, clutching the pavement to save their lives."

Hitler was arrested and put on trial for treason. If found guilty, Hitler faced the death penalty. Others tried for this offence included Schreck, Eric Ludendorff, Wilhelm Frick, Wilhelm Brückner, Hermann Kriebel, Ernst Roehm, Friedrich Weber and Ernst Pohner. It soon became clear that the Bavarian authorities were unwilling to punish the men too severely.

The State Prosecutor, Ludwig Stenglein, was remarkably tolerant towards Hitler in court: "His (Hitler) honest endeavour to reawaken the belief in the German cause among an oppressed and disarmed people.... His private life has always been clean, which deserves special approbation in view of the temptations which naturally came to him as an acclaimed party leader.... Hitler is a highly gifted man who, coming from a simple background, has, through serious and hard work, won for himself a respected place in public life. He dedicated himself to the ideas that inspired him to the point of self-sacrifice, and as a soldier he fulfilled his duty in the highest measure."

At his trial Adolf Hitler was allowed to turn the proceedings into a political rally. "The army we have trained is growing from day to day, from hour to hour. At this very time I hold to the proud hope that the hour will come when these wild bands will be formed into battalions, the batallions into regiments, the regiments into divisions.... Then from our bones and our graves will speak the voice of that court which alone is empowered to sit in judgment on us all. For not you, gentlemen, will deliver judgment on us; that judgment will be pronounced by the eternal court of history, which will arbitrate the charge that has been made against us.... That court will judge us, will judge the Quartermaster General of the former army, will judge his officers and soldiers as Germans who wanted the best for their people and their Fatherland, who were willing to fight and die."

William L. Shirer, the author of The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich (1964), has pointed out that an important figure protecting Hitler was Franz Gürtner: "From beginning to end he dominated the courtroom. Franz Gürtner, the Bavarian Minister of Justice and an old friend and protector of the Nazi leader, had seen to it that the judiciary would be complacent and lenient. Hitler was allowed to interrupt as often as he pleased, cross-examine witnesses at will and speak on his own behalf at any time and at any length - his opening statement consumed four hours, but it was only the first of many long harangues."

Hitler was found guilty he only received the minimum sentence of five years. Ludendorff was acquitted and Schreck and the others, although found guilty, only received very light sentences. The men were sent to Landsberg Castle in Munich and Hitler was allowed to write and publish Mein Kampf.

Gerhard Maurer and Carl Schneider

After his release from Landsberg Castle Hitler decided he needed his own personal bodyguard and on 9th November, 1925 the Saalschutz became known as the Schutzstaffel (SS). The word Schutzstaffel means "defence echelon". As Louis L. Snyder has pointed out: "The name was universally abbreviated to SS, not in Roman or Gothic letters but written as a lightening flash in imitation of ancient runic characters. The SS was known as the Black Order." Julius Schreck became its first leader and he was told that the SS was an independent organization alongside, but subordinate to, the Sturm Abteilung (SA).

Andrew Mollo, the author of To The Death's Head: The Story of the SS (1982): "Although mostly unemployed, SS men were expected to provide their own uniforms which also differed from those of the SA. SS men wore the brown shirt but, unlike the SA, they had a black cap adorned with a silver death's head, a black tie and black breeches, and the swastika armband was withdrawn from SS men who had infringed minor regulations."

Schreck resigned as Reichführer-SS in 1926 and went to work for Hitler. After Emil Maurice was sacked in 1931 Schreck became Hitler's private chauffeur. According to Albert Speer, the author of Inside the Third Reich (1970), during this period, Hitler's inner-circle included Schreck, Joseph Goebbels, Herman Goering, Hermann Esser, Wilhelm Brückner, Sepp Diettrich, Julius Schaub, Heinrich Hoffmann, Franz Schwarz, Max Amann and Otto Dietrich: "Evenings he usually had some trusty companions about: Schreck, his chauffeur for many years; Sepp Dietrich, the commander of his SS bodyguard; Dr. Otto Dietrich, the press chief; Brückner and Schaub, his two adjutants; and Heinrich Hoffmann, his official photographer. Since the table held no more than ten persons, this group almost completely filled it. For the midday meal, on the other hand, Hitler's old Munich comrades foregathered, such as Amann, Schwarz and Esser... I saw very little of Himmler, Roehm or Streicher at these meals, but Goebbels and Goering were often there."

Julius Schreck died of meningitis on 16th May, 1936.

Primary Sources

(1) Albert Speer, Inside the Third Reich (1970)

Evenings he usually had some trusty companions about: Schreck, his chauffeur for many years; Sepp Dietrich, the commander of his SS bodyguard; Dr. Otto Dietrich, the press chief; Brückner and Schaub, his two adjutants; and Heinrich Hoffmann, his official photographer. Since the table held no more than ten persons, this group almost completely filled it. For the midday meal, on the other hand, Hitler's old Munich comrades foregathered, such as Amann, Schwarz and Esser... I saw very little of Himmler, Roehm or Streicher at these meals, but Goebbels and Goering were often there.