On this day on 25th April

On this day in 1599 Oliver Cromwell, the son of Robert Cromwell and Elizabeth Steward Cromwell, was born in Huntingdon. Oliver's great-grandfather, Morgan Williams, a Welshman who had settled in Putney as an innkeeper and brewer, had the good fortune to marry Katherine, the sister of Thomas Cromwell, before he was employed as chief minister by Henry VIII.

During the Dissolution of the Monasteries, Morgan and his son, Richard, received enough confiscated church lands to become one of the most prominent families in Huntingdonshire. This included three abbeys, two priories and a nunnery, that was worth about £2,500 a year. In gratitude, Richard changed the family name to Cromwell.

By the time Oliver was born, Robert Cromwell's older brother, Sir Oliver Cromwell owned a large but debt-laden estate. Robert in contrast inherited a modest cluster of urban properties in and around the town and had an income of around £300 per annum and a seven-room town house. However, he had considerable social status and had represented Huntington in the parliament of 1593.

Oliver attended Huntington Grammar School. Dr Thomas Beard was not only the schoolmaster but the rector of St John's Church. He was also a sincere Puritan who had written pamphlets on the doctrine of predestination (the doctrine that all events have been willed by God). One of these pamphlets argued that the Pope was the Anti-christ. Although he later developed strong religious views, as a schoolboy he was not a good student: "He was of a stubborn disposition that made correction difficult; he played truant, he broke down hedges and stole the birds from the dovecotes."

It is claimed that he was a spoilt child because he was the only boy in a family of six sisters (three other children had died in infancy). "We may speculate on the effects of this petticoat environment; by all accounts (some of them not very reliable) he grew up to be a rough, boisterous, practical-joking boy, with no effeminate characteristics." According to one source "Cromwell had an unusually close, tender and long-term relationship with his mother".

In April 1616 he began attending Sidney Sussex College. The Master of the College was Samuel Ward and he was accused of making it "a hotbed of Puritanism". He did well in mathematics but does not appear to have been very interested in "the humanities and civil law" to the dismay of his parents. It seems that during this period he had a great enthusiasm for "football, cudgelling, wrestling and an early form of cricket".

Cromwell left Cambridge University in June, 1617, on the death of his father and took over control of the family estate. On 22nd August 1620, Oliver Cromwell married Elizabeth Bourchier. His wife was the daughter of Sir John Bourchier, a London merchant, a fur-dealer and leather dresser, who had done well enough to be knighted and buy a country estate in Essex. In his first years of married life he consulted a London physician who recorded in his case-book that Cromwell was "depressed to an abnormal degree". Another doctor suggested that he suffered from hypochondria. (7)

Over the next few years Elizabeth Cromwell gave birth to nine children: five boys and four girls. Only one child (James) died in infancy. Little is known of the relationship between Oliver and Elizabeth beyond the unmannered deep affection of their letters to one another. His marriage brought him into contact with leading members of the London merchant community. It could have also been the reason for his conversion to Puritanism during this period. (8)

Cromwell wrote afterwards: "You know what my manner of life hath been. Oh, I lived in and loved darkness, and hated the light. I was a chief, the chief of sinners. This is true: I hated godliness, yet God had mercy on me. Oh the riches of his mercy! Praise Him for me, pray for me, that he who hath begun a good work would perfect it to the day of Christ."

In 1628, Oliver Cromwell's childless uncle, Richard Cromwell died, leaving his property to his nephew. The following year he was involved in a dispute with a local powerful landowner. It is believed that his new hard-line religious views was a factor in this conflict. Jasper Ridley suggests that Cromwell "championed the cause of the local commoners against the Mayor of Huntingdon who was threatening their privileges, and against the attempts of the Earl of Manchester to enclose the Fens." In December, 1630, he was called before the Privy Council and forced to apologize. In May, 1631, he sold nearly all of his land in Huntingdon for the sum of £1,800 and moved to St Ives, 4 miles away.

John Morrill has pointed out: "Despite his connections with ancient riches, Cromwell's economic status was much closer to that of the middling sort and urban merchants than to the country gentry and governors. He always lived in towns, not in a country manor house; and he worked for his living. He held no important local offices and had no tenants or others dependent upon him beyond a few household servants."

During this period Cromwell came into conflict with Charles I, who attempted to make money from selling knighthoods. In the 16th century, all men with land worth £40 a year were required to pay for a knighthood. However, rapid inflation pushed many into this category "who were below the social level of knights and had no relish for an honour which might well oblige them to perform functions in the local communities for which they had neither the leisure, the qualifications, nor the necessary status."

Cromwell and other Puritans refused to buy what had once been an honour. Charles reacted to this by fining those who were unwilling to pay this money. In April 1631 Cromwell and six others from his neighbourhood appeared before the royal commissioners for repeatedly refusing to buy a knighthood. He was found guilty and fined £10. It was reported that Cromwell was so unhappy about this that he considered the idea of going to live in North America.

© National Portrait Gallery

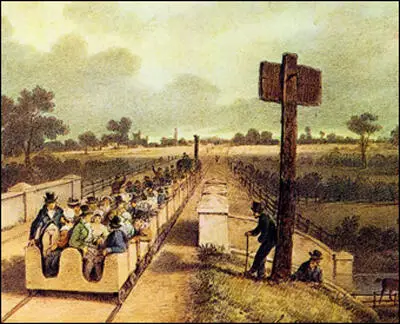

On this day in 1825 George Stephenson gave evidence to the House of Commons committee looking into the proposed Liverpool & Manchester Railway. Edward Alderson, the counsel employed by those opposing the railway, severely criticised the evidence given by Stephenson. "This railway is the most absurd scheme that ever entered into the head of a man to conceive. Mr. Stephenson never had a plan - I do not believe he is capable of making one. He is either ignorant or something else which I will not mention. His is a mind perpetually fluctuating between opposite difficulties; he neither knows whether he is to make bridges over roads or rivers, or of one size or another; or to make embankments, or cuttings, or inclined planes, or in what way the thing is to be carried into effect. When you put a question to him upon a difficult point, he resorts to two or three hypothesis, and never comes to a decided conclusion. Is Mr. Stephenson to be the person upon whose faith this Committee is to pass this Bill involving property to the extent of £400,000/£500,000 when he is so ignorant of his profession as to propose to build a bridge not sufficient to carry off the flood water of the river or to permit any of the vessels to pass which of necessity must pass under it."

crossing the Bridgewater Canal by A. B. Clayton.

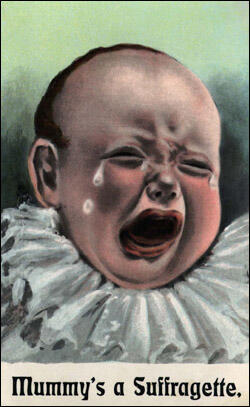

On this day in 1906 William Cremer, the Liberal Party MP for Haggerston and the founder of the Anti-Suffrage League, makes a speech against women's suffrage.

He had always contended that if we opened the door and enfranchised ever so small a number of females, they could not possibly close it, and that it ultimately meant adult suffrage. The government of the country would therefore be handed over to a majority who would not be men, but women. Women are creatures of impulse and emotion and did not decide questions on the ground of reason as men did.

He was sometimes described as a woman-hater, but he had had two wives, and he thought that was the best answer he could give to those who called him a woman-hater. He was too fond of them to drag them into the political arena and to ask them to undertake responsibilities, duties and obligations which they did not understand and did not care for.

What did one find when one got into the company of women and talked politics? They were soon asked to stop talking silly politics, and yet that was the type of people to whom we were invited to hand over the destinies of the country.

It was not only because he thought that women were unfitted by their physical nature to exercise political power, but because he believed that the majority of them did not want it and would vote against it, that he asked the House to pause before they took the step suggested by the honorable member for Merthyr Tydfil (Keir Hardie). He believed that if women were enfranchised the end would be disastrous to all political parties. He therefore asked the House to pause before it took a step from which it could never retreat.

On this day in 1908 journalist Edward R. Murrow, the son of Quakers,was born in Polecat Creek, Guildford County. Murrow attended Edison High School before studying at Washington State College. In 1932 he was appointed assistant director of the Institute of International Education.

Murrow joined the Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS) in 1935 as director of talks. His appointments included William L. Shirer in Germany. Two years later he was sent to London to arrange concerts for the radio network. He also made broadcasts about politics and in September 1938 he reported on the Munich Agreement signed by Neville Chamberlain and Adolf Hitler: "Thousands of people are standing in Whitehall and lining Downing Street, waiting to greet the Prime Minister upon his return from Munich. Certain afternoon papers speculate concerning the possibility of the Prime Minister receiving a knighthood while in office, something that has happened only twice before in British history. Others say that he should be the next recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize."

Murrow was a critic of appeasement and on 2nd September, 1939, he argued: "Some people have told me tonight that they believe a big deal is being cooked up which will make Munich and the betrayal of Czechoslovakia look like a pleasant tea party. I find it difficult to accept this thesis. I don't know what's in the mind of the government, but I do know that to Britishers their pledged word is important, and I should be very much surprised to see any government which betrayed that pledge remain long in office. And it would be equally surprising to see any settlement achieved through the mediation of Mussolini produce anything other than a temporary relaxation of the tension."

Edward R. Murrow remained in London after the outbreak of the Second World War and his eyewitness reports on the Blitz made him a national figure in the United States. On 10th September 1940 he reported: "We could see little men shovelling those fire bombs into the river. One burned for a few minutes like a beacon right in the middle of a bridge. Finally those white flames all went out. No one bothers about the white light, it's only when it turns yellow that a real fire has started. I must have seen well over a hundred fire bombs come down and only three small fires were started. The incendiaries aren't so bad if there is someone there to deal with them, but those oil bombs present more difficulties. As I watched those white fires flame up and die down, watched the yellow blazes grow dull and disappear, I thought, what a puny effort is this to burn a great city."

In May 1940 Winston Churchill became prime minister: "Winston Churchill, who has held more political offices than any living man, is now Prime Minister. He is a man without a party. For the last seven years he has sat in the House of Commons, a rather lonesome and often bellicose figure, voicing unheeded warnings of the rising tide of German military strength. Now, at the age of sixty-five, Winston Churchill, plump, bald, with massive round shoulders, is for the first time in his varied career of journalist, historian and politician the Prime Minister of Great Britain. Mr. Churchill now takes over the supreme direction of Britain's war effort at a time when the war is rapidly moving toward Britain's doorstep. Mr. Churchill's critics have said that he is inclined to be impulsive and, at times, vindictive. But in the tradition of British politics he will be given his chance. He will probably take chances. But if he brings victory, his place in history is assured."

During the Second World War Murrow flew on more than forty raids in Europe. He reported on 3rd December, 1943: "Berlin was a kind of orchestrated hell, a terrible symphony of light and flame. It isn't a pleasant kind of warfare - the men doing it speak of it as a job. Yesterday afternoon, when the tapes were stretched out on the big map all the way to Berlin and back again, a young pilot with old eyes said to me, "I see we're working again tonight."That's the frame of mind in which the job is being done. The job isn't pleasant; it's terribly tiring. Men die in the sky while others are roasted alive in their cellars. Berlin last night wasn't a pretty sight. In about thirty-five minutes it was hit with about three times the amount of stuff that ever came down on London in a night-long blitz. This is a calculated, remorseless campaign of destruction.

In November 1944 Murrow reported on the new German weapon, the V-2 Flying Bombs: "I shall try to say something about V-2, the German rockets that have fallen on several widely scattered points in England. The Germans, as usual, made the first announcement and used it to blanket the fact that Hitler failed to make his annual appearance at the Munich beer cellar. The German announcement was exaggerated and inaccurate in some details, but not in all. For some weeks those of us who had known what was happening had been referring to these explosions, clearly audible over a distance of fifteen miles, as 'those exploding gas mains'. It is impossible to give you any reliable report on the accuracy of this weapon because we don't know what the Germans have been shooting at. They have scored some lucky and tragic hits, but as Mr. Churchill told the House of Commons, the scale and the effects of the attack have not hitherto been significant. That is, of course, no guarantee that they will not become so. This weapon carries an explosive charge of approximately one ton. It arrives without warning of any kind. The sound of the explosion is not like the crump of the old-fashioned bomb, or the flat crack of the flying bomb; the sound is perhaps heavier and more menacing because it comes without warning. Most people who have experienced war have been saved repeatedly by either seeing or hearing; neither sense provides warning or protection against this new weapon."

In 1945 Murrow moved to mainland Europe, first reporting the war from France and later in Germany. He was also with Allied troops when they entered the extermination camps at Buchenwald. "As I walked down to the end of the barracks, there was applause from the men too weak to get out of bed. It sounded like the hand clapping of babies; they were so weak. As we walked out into the courtyard, a man fell dead. Two others - they must have been over sixty - were crawling toward the latrine. I saw it but will not describe it."

A prisoner commented: "You will write something about this, perhaps? "To write about this you must have been here at least two years, and after that - you don't want to write any more." Murrow continued to search the camp: "We proceeded to the small courtyard. The wall was about eight feet high; it adjoined what had been a stable or garage. We entered. It was floored with concrete. There were two rows of bodies stacked up like cordwood. They were thin and very white.... It appeared that most of the men and boys had died of starvation; they had not been executed. But the manner of death seemed unimportant. Murder had been done at Buchenwald. God alone knows how many men and boys have died there during the last twelve years. Thursday I was told that there were more than twenty thousand in the camp. There had been as many as sixty thousand. Where are they now?" Murrow finished his report from Buchenwald with the words: "I pray you to believe what I have said about Buchenwald. I have reported what I saw and heard, but only part of it. For most of it I have no words. If I've offended you by this rather mild account of Buchenwald, I'm not in the least sorry."

In the late 1940s Murrow supported the persecution of members of the American Communist Party. This included the arrest of its leaders, Eugene Dennis, William Z. Foster, Benjamin Davis, John Gates, Robert G. Thompson, Gus Hall, Benjamin Davis, Henry M. Winston and Gil Green under the Alien Registration Act. In sentenced to the men to five years in prison and a $10,000 fine (Thompson, because of his war record, received only three years). Murrow argued on 14th October 1949: "One result of the verdict may be to convince a number of people that the Communists are not just another political party. In view of the mass of evidence produced in judge Medina's court, it will be pretty difficult in the future for anyone to maintain that he joined and worked for the Communist Party without really knowing that it advocated violent revolution. There have been many serious proposals to control, contain or outlaw the Communist Party in this country, efforts to hog-tie them without strangling our liberties with the loose end of the rope. It is both delicate and dangerous business. We can't legislate loyalty. But nevertheless the question of the control of subversion is one of the most important confronting this country."

Murrow became concerned about the activities of Joseph McCarthy and suggested that his friend, Raymond Gram Swing, should debate with Ted C. Kirkpatrick, the co-author of Red Channels, at the Radio Executives Club on 19th October, 1950. Swing argued: "I shall be brief in giving the reasons why I believe the approach of Red Channels is utterly un-American. It is a book compiled by private persons to be sold for profit, which lists the names of persons for no other reason than to suggest them as having Communist connections of sufficient bearing to render them unacceptable to American radio. The list has been drawn up from reports, newspaper statements and letterheads, without checking, and without testing the evidence, and without giving a hearing to anyone whose name is listed. There is no attempt to evaluate the nature of the Communist connections. A number of organizations are cited as those with whom the person is affiliated, but with no statement as to the nature of the association."

In response to this speech, Kirkpatrick's magazine, Counterattack , published an article on Swing where it was claimed that: "The National Council of American Soviet Friendship was cited as subversive in 1947; in late 1948 he was still listed as one of its sponsors.. In his broadcasts Swing often followed an appeasement line and defended Russian policy." The magazine went on to attack an article he had written for the Atlantic Monthly where he had argued that the people of the United States "can choose whether to work with the Soviet Union as a partner or whether to surrender to memories and fears." As a result of these attacks, Swing was forced to resign the Voice of America (VOA).

In 1951 he inaugurated in-depth television journalism with his weekly, 30 minute, See It Now. He also presented Person to Person, where he interviewed well-known public figures. Murrow, like many other liberal journalists, became increasingly concerned about the impact that Joe McCarthy anti-communist campaign was having on America. He was particularly upset by the attacks on George Marshall, a man Murrow regarded as "the greatest living American". A friend of Murrow's, Larry Duggan, Director of the Institute of International Education (IIC), was also accused of being a member of the American Communist Party and ordered to appear before the House of Un-American Activities Committee. Unwilling to name radicals he had associated with in his youth, Duggan committed suicide by jumping from his sixteenth-floor office.

Murrow now decided to speak out and complained about McCarthy's treatment of Henry Dexter White, who Joe McCarthy had recently accused of being a communist spy. Murrow was now accused of being part of the "Moscow conspiracy" and it was suggested that as "an anti-anti-Communist was as dangerous as a Communist".

In early 1954 Murrow and his producer, Fred Friendly, decided to devote an edition of See It Now to McCarthyism. CBS was unhappy with the idea and had been one of those television companies that had been part of the blacklist to prevent people named by Joe McCarthy from being employed in the industry. The CBS introduced its own "loyalty oath" contract and sacked some workers because they had previously been members of the Communist Party. CBS and the sponsor of the programme refused to publicize the proposed McCarthy programme, and as a result, Murrow and Friendly decided to use $1,500 their own money to pay for ads in the newspapers.

On 9th March, 1954, Murrow's See It Now programme, dealt with McCarthyism. During the broadcast Murrow commented: "The line between investigating and persecuting is a very fine one and the junior Senator from Wisconsin has stepped over it repeatedly. We will not be driven by fear into an age of unreason, if we dig deep into our own history and our doctrine and remember that we are not descended from fearful men, not men who feared to write, to speak, to associate, and to defend causes which were for the moment unpopular. This is no time for men who oppose Senator McCarthty's methods to keep silent. We can deny our heritage and our history, but we cannot escape responsibility for the result."

The day after the programme CBS announced that 12,348 people phoned in comments about the programme, and the opinions went fifteen-to-one in Murrow's favor. The sponsors also reported receiving over 4,000 letters, with the vast majority supporting Murrow's stance. The New York Herald Tribune, a Republican newspaper, said Murrow had presented "a sober and realistic appraisal of McCarthyism and the climate in which it flourishes." Jack Gould, television critic for The New York Times, called the broadcast "crusading journalism of high responsibility and genuine courage", an "incisive visual autopsy of the Senator's record'. However, Jack O'Brian, radio-TV columnist for Hearst's right-wing New York Journal-American, labelled the broadcast a "smear".

When Joe McCarthy was asked what he thought of the programme he replied: "I never listen to the extreme left-wing, bleeding heart elements of radio and TV." Several times over the next few days he attacked Murrow. He claimed that Murrow had "sponsored a communist school in Moscow" and "acted for the Russian espionage and propaganda organization known as VOKS, a job which would normally be done by the Russian secret police." He claimed that Murrow's friendship with Harold Laski, a leading figure in the British Labour Party, was an example of his pro-Communist sympathies.

The persecution of those opposed to McCarthyism continued. When the See It Now programme ended on 9th March, Don Hollenbeck, came on the air with the regular 11.00 p.m. news and said: "I want to associate myself with every word just spoken by Ed Murrow." Hollenbeck was denounced in the pro-McCarthy press as a communist. After three months of smears, Hollenbeck, unable to take the strain, committed suicide.

McCarthy's downfall came as a result of the televised senate investigations into the United States Army. One newspaper, the Louisville Courier-Journal, reported that: "In this long, degrading travesty of the democratic process McCarthy has shown himself to be evil and unmatched in malice." Leading politicians in both parties, had been embarrassed by McCarthy's performance and on 2nd December, 1954, a censure motion condemned his conduct by 67 votes to 22.

In the late 1950s Edward R. Murrow became disillusioned with television broadcasting. He disagreed with the emphasis being placed on producing entertainment-based programmes. Murrow left broadcasting in 1961 and joined the United States Information Agency (USIA). However, suffering from lung cancer, he was forced him to resign in 1964. The cancer spread to the brain and Edward Murrow died at Glen Arden, on 27th April, 1965.

On this day in 1913 the Cat and Mouse Act becomes law. In 1913 the Women's Social & Political Union increased its campaign to destroy public and private property. The women responsible were often caught and once in prison they went on hunger-strike. Determined to avoid these women becoming martyrs, the government introduced the Prisoner's Temporary Discharge of Ill Health Act. Suffragettes were now allowed to go on hunger strike but as soon as they became ill they were released. Once the women had recovered, the police re-arrested them and returned them to prison where they completed their sentences. This successful means of dealing with hunger strikes became known as the Cat and Mouse Act.

On this day in 1915 Allied forces begin the Gallipoli Campaign. The attack established two beachheads at Helles and Gaba Tepe. Another major landing took place at Sulva Bay on 6th August. By this time they arrived the Turkish strength in the region had also risen to fifteen divisions. Attempts to sweep across the peninsula by Allied forces ended in failure. By the end of August the Allies had lost over 40,000 men. General Ian Hamilton asked for 95,000 more men, but although supported by Churchill, Lord Kitchener was unwilling to send more troops to the area.

In the words of one historian, "In the annals of British military incompetence Gallipoli ranks very high indeed."Churchill was blamed for the failed operation and Asquith told him he would have to be moved from his current post. Asquith was also involved in developing a coalition government. The Conservative leader, Andrew Bonar Law, became Minister of the Colonies and Churchill's long-term enemy, Arthur Balfour, became the new First Lord of the Admiralty. Churchill was now relegated to the post of the Chancellorship of the Duchy of Lancaster.

On 14th October, Hamilton was replaced by General Charles Munro. After touring all three fronts Munro recommended withdrawal. Lord Kitchener, initially rejected the suggestion but after arriving on 9th November 1915 he visited the Allied lines in Greek Macedonia, where reinforcements were badly needed. On 17th November, Kitchener agreed that the 105,000 men should be evacuated and put Monro in control as Commander-in-Chief Mediterranean.

About 480,000 Allied troops took part in the Gallipoli campaign, including substantial British, French, Senegalese, Australian, New Zealand and Indian troops. The British had 205,000 casualties (43,000 killed). There were more than 33,600 ANZAC losses (over one-third killed) and 47,000 French casualties (5,000 killed). Turkish casualties are estimated at 250,000 (65,000 killed). "The campaign is generally regarded as an example of British drift and tactical ineptitude."

In November, 1915, Winston Churchill was removed as a member of the War Council. He now resigned as a minister and he told Asquith that his reputation would rise again when the whole story of the Dardanelles came out. He also criticised Asquith in the way the war had so far been managed. He ended his letter with the words: "Nor do I feel in times like these able to remain in well-paid inactivity. I therefore ask you to submit my resignation to the King. I am an officer, and I place myself unreservedly at the disposal of the military authorities, observing that my regiment is in France."

On this day in 1941 Nina Masel writes about joining the Women's Auxiliary Air Force. "Now a member of the WAAF, I find myself with an extraordinary amount of free time on my hands. My job consists for the most part of sitting at a table with ear-phones on my head - waiting. The majority of the girls are intensely bored by the job which is extremely interesting when work comes through, but in which there is very seldom any work to do. We work on shifts of 5-8 hours each and nearly all the men and women keep themselves awake by talking or reading. The reasons girls gave for joining up - between ourselves of course - not to the officers, - had very little to do with 'doing one's bit'. General boredom with life was the keynote. Nearly everyone said that on the night before she left, she almost decided to back out and that all the way up on the train, she kept thinking 'What a mug I was. Why did I join?' Afterwards, opinion was divided according to how the girls took to the life. There were two deserters one week. But on the whole, those who hated it - small minority - wouldn't go home because of the 'I told you so's of their friends. They had all been discouraged from joining up by their friends. My friends also discouraged me from joining. In the East End it was considered a fine thing to do, almost an honour, but my friends told me I'd be bored. In Romford, on the other hand, the information was received with raised eyebrows. 'The WAAF', I was told, 'is merely the groundsheet for the Army'. There is a WAAF camp near Romford and its reputation was terrible."

The Women's Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF) was formed in June 1939. The main reason for this service was to release men for combat posts. Women were accepted between the ages of 17 and 44. Between December 1939 and June 1945 numbers increased from 8,800 to 153,000. The work done by the WAAF covered virtually every activity carried out by men except flying. one of their most important tasks included control over Barrage Balloons.

On this day in 1941 General Erwin Rommel and his army enter Egypt. Rommel's first offensive has been described as a "masterpiece of desert warfare by a general with no experience in this field". The man who became known as the "Desert Fox" pushed 1,500 miles into the country. General Archibald Wavell attempted a counter-attack on 17th June, 1941, but his troops were halted at Halfaya Pass. Although Wavell held in high esteem by General Alan Brooke, the Chief of General Staff, Winston Churchill had lost confidence in him and replaced him by General Claude Auchinleck.

Basil Liddell Hart, the author of The Other Side of the Hill (1951) has argued: "From 1941 onwards the names of all other German generals came to be overshadowed by that of Erwin Rommel. He had the most startling rise of any-from colonel to field-marshal. He was an outsider, in a double sense - as he had not qualified for high position in the hierarchy of the General Staff, while he long performed in a theatre outside Europe.... While Rommel owed much to Hitler's favour, it was testimony to his own dynamic personality that he first impressed himself on Hitler's mind, and then impressed his British opponents so deeply as to magnify his fame beyond Hitler's calculation."

Brian Horrocks who fought in the British Army during the Desert War later claimed: "Rommel was probably the best armoured corps commander produced by either side. Utterly fearless, full of drive and initiative, he was always up in front where the battle was fiercest. If his opponent made a mistake, Rommel was on to it like a flash, and he never hesitated to take personal command of a regiment or battalion if he thought fit. On one occasion he was found lifting mines with his own hands. His popularity with the soldiers was immense, but a great many officers resented his interference with their commands."

On this day in 1942 Adolf Hitler tells Joseph Goebbels that he was going to increase terror air-raids on Britain. "He said he would repeat these raids night after night until the English were sick and tired of terror attacks. He shares my opinion absolutely that cultural centres, health resorts and civilian resorts must be attacked now. There is no other way of bringing the English to their senses. They belong to a class of human beings with whom you can only talk after you have first knocked out their teeth."