On this day on 16th July

On this day in 1546 Anne Askew was executed. Her executioner helped her die quickly by hanging a bag of gunpowder around her neck. Also executed at the same time was John Lascelles, John Hadlam and John Hemley. John Bale wrote that “Credibly am I informed by various Dutch merchants who were present there, that in the time of their sufferings, the sky, and abhorring so wicked an act, suddenly altered colour, and the clouds from above gave a thunder clap, not unlike the one written in Psalm 76. The elements both declared wherein the high displeasure of God for so tyrannous a murder of innocents."

Anne Askew, the second daughter of Sir William Askew (1489–1541) and his first wife, Elizabeth Wrottesley, was born in Stallingborough in 1521.

Her father, who was a landowner was knighted in 1513, and in 1521, at about the time of Anne's birth, he was appointed high sheriff of Lincolnshire. He also sat as MP for Grimsby in 1529.

Askew received a good education from home tutors. When she was fifteen her family forced her to marry Thomas Kyme. Anne rebelled against her husband by refusing to adopt his surname. The couple also argued about religion. Anne was a supporter of Martin Luther, while her husband was a Catholic.

From her reading of the Bible she believed that she had the right to divorce her husband. For example, she quoted St Paul: "If a faithful woman have an unbelieving husband, which will not tarry with her she may leave him"? Askew was well connected. One of her brothers, Edward Askew, was cup-bearer to the king, and her half-brother Christopher, was gentleman of the privy chamber.

Alison Plowden has argued that "Anne Askew is an interesting example often educated, highly intelligent, passionate woman destined to become the victim of the society in which she lived - a woman who could not accept her circumstances but fought an angry, hopeless battle against them."

In 1544 Anne Askew decided to travel to London to meet Henry VIII and request a divorce from her husband. This was denied and documents show that a spy was assigned to keep a close watch on her behaviour. She made contact with Joan Bocher, a leading figure in the Anabaptists. One spy who had lodgings opposite her own reported that "at midnight she beginneth to pray, and ceaseth not in many hours after." Another contact was John Lascelles, who had previously worked for Thomas Cromwell, and was involved in the downfall of Catherine Howard.

In March 1545 she was arrested on suspicion of heresy. She was questioned about a book she was carrying that had been written by John Frith, a Protestant priest who had been burnt for heresy in 1533, for claiming that neither purgatory nor transubstantiation could be proven by Holy Scriptures. She was interviewed by Edmund Bonner, the Bishop of London who had obtained the nickname of "Bloody Bonner" because of his ruthless persecution of heretics.

After a great deal of debate Anne Askew was persuaded to sign a confession which amounted to an only slightly qualified statement of orthodox belief. With the help of her friend, Edward Hall, the Under-Sheriff of London, she was released after twelve days in prison. Askew's biographer, Diane Watt, argues: "It would appear that at this stage Bonner was concerned more about the heterodoxy of Askew's beliefs than with her connections and contacts, and that he principally wanted to rid himself of a woman whom he found obstinate and vexatious. Her treatment during her first examination suggests, therefore, that Askew's opponents did not yet view her as particularly influential or important." Askew was released and sent back to her husband. However, when she arrived back to Lincolnshire she went to live with her brother, Sir Francis Askew.

In February 1546 conservatives in the Church of England, led by Stephen Gardiner, bishop of Winchester, began plotting to destroy the radical Protestants. He gained the support of Henry VIII. As Alison Weir has pointed out: "Henry himself had never approved of Lutheranism. In spite of all he had done to reform the church of England, he was still Catholic in his ways and determined for the present to keep England that way. Protestant heresies would not be tolerated, and he would make that very clear to his subjects." In May 1546 Henry gave permission for twenty-three people suspected of heresy to be arrested. This included Anne Askew.

Gardiner selected Askew because he believed she was associated with Henry's sixth wife, Catherine Parr. Catherine also criticised legislation that had been passed in May 1543 that had declared that the "lower sort" did not benefit from studying the Bible in English. The Act for the Advancement of the True Religion stated that "no women nor artificers, journeymen, serving men of the degree of yeomen or under husbandmen nor labourers" could in future read the Bible "privately or openly". Later, a clause was added that did allow any noble or gentlewoman to read the Bible, this activity must take place "to themselves alone and not to others". Catherine ignored this "by holding study among her ladies for the scriptures and listening to sermons of an evangelical nature".

Gardiner believed the Queen was deliberately undermining the stability of the state. Gardiner tried his charm on Anne Askew, begging her to believe he was her friend, concerned only with her soul's health, she retorted that that was just the attitude adopted by Judas "when he unfriendly betrayed Christ". On 28th June she flatly rejected the existence of any priestly miracle in the eucharist. "As for that ye call your God, it is a piece of bread. For a more proof thereof... let it but lie in the box three months and it will be mouldy."

Gardiner instructed Sir Anthony Kingston, the Constable of the Tower of London, to torture Askew in an attempt to force her to name Catherine Parr and other leading Protestants as heretics. Kingston complained about having to torture a woman (it was in fact illegal to torture a woman at the time) and the Lord Chancellor Thomas Wriothesley and his assistant, Richard Rich took over operating the rack. Despite suffering a long period on the rack, Askew refused to name those who shared her religious views. According to Askew: "Then they did put me on the rack, because I confessed no ladies or gentlemen, to be of my opinion... the Lord Chancellor and Master Rich took pains to rack me with their own hands, till I was nearly dead. I fainted... and then they recovered me again. After that I sat two long hours arguing with the Lord Chancellor, upon the bare floor... With many flattering words, he tried to persuade me to leave my opinion... I said that I would rather die than break my faith." Afterwards, Anne's broken body was laid on the bare floor, and Wriothesley sat there for two hours longer, questioning her about her heresy and her suspected involvement with the royal household. Askew was removed to a private house to recover and once more offered the opportunity to recant. When she refused she was taken to Newgate Prison to await her execution. On 16th July 1546, Agnew "still horribly crippled by her tortures" was carried to execution in Smithfield in a chair as she could not walk and every movement caused her severe pain. It was reported that she was taken to the stake which had a small seat attached to it, on which she sat astride. Chains were used to bind her body firmly to the stake at the ankles, knees, waist, chest and neck.

Bishop Stephen Gardiner had a meeting with Henry VIII after the execution of Anne Askew and raised concerns about his wife's religious beliefs. Henry, who was in great pain with his ulcerated leg and at first he was not interested in Gardiner's complaints. However, eventually Gardiner got Henry's agreement to arrest Catherine Parr and her three leading ladies-in-waiting, "Herbert, Lane and Tyrwhit" who had been involved in reading and discussing the Bible.

Henry then went to see Catherine to discuss the subject of religion. Probably, aware what was happening, she replied that "in this, and all other cases, to your Majesty's wisdom, as my only anchor, Supreme Head and Governor here in earth, next under God". He reminded her that in the past she had discussed these matters. "Catherine had an answer for that too. She had disputed with Henry in religion, she said, principally to divert his mind from the pain of his leg but also to profit from her husband's own excellent learning as displayed in his replies." Henry replied: "Is it even so, sweetheart? And tended your arguments to no worse end? Then perfect friends we are now again, as ever at any time heretofore." Gilbert Burnett has argued that Henry put up with Catherine's radical views on religion because of the good care she took of him as his nurse.

The next day Chancellor Thomas Wriothesley arrived with a detachment of soldiers to arrest Catherine. Henry told him he had changed his mind and sent the men away. Glyn Redworth, the author of In Defence of the Church Catholic: The Life of Stephen Gardiner (1990) has disputed this story because it relies too much on the evidence of John Foxe, a leading Protestant at the time. However, David Starkey, the author of Six Wives: The Queens of Henry VIII (2003) has argued that some historians "have been impressed by the wealth of accurate circumstantial detail, including, in particular, the names of Catherine's women."

On this day in 1882 Mary Todd Lincoln, First Lady of the United States, died. Mary Todd, the daughter of Eliza Parker and Robert Smith Todd, was born in Lexington, Kentucky on 13th December, 1818. Her father was a wealthy banker and lawyer who was an active member of the Whig Party. Her mother died when Mary was six and she did not get on with her stepmother.

In 1839 Mary went to live with her sister in Springfield, Illinois. While there she met Abraham Lincoln. Despite objections from her family, the couple were married in November, 1842. The couple had four sons: Robert Lincoln (1843-1926), Edward Lincoln (1846-50), William Lincoln (1850-62) and Thomas Lincoln (1853-1871). Three of the boys died young and only Robert lived long enough to marry and have children.

When Abraham Lincoln went to Washington to take his seat in the House of Representatives in 1847, Mary and the children went along. Lincoln felt that Mary "hindered me some in attending to business" and the following year the rest of the family returned to Springfield.

The death of Edward Lincoln on 1st February, 1850, caused Mary to have a spiritual crisis. She ceased attending Episcopal services and became a member of the Presbyterian Church.

Mary did not share her husbands progressive political views but supported him in his campaign to become president. After his victory in 1860 Mary joined him in Washington. Uncomfortable in her new surroundings, she tended to over-compensate by spending large sums of money on clothes. This resulted in her building up enormous debts.

William Lincoln died in 1862. Devastated by the loss of her second son, Mary became interested in spiritualism. Friends became concerned about her mental health when she began to claim that William's spirit came to visit her at night.

During the American Civil War Mary came under the influence of Charles Sumner. She now became an ardent abolitionist and became more radical on this issue than her husband. Her seamstress and former slave, Elizabeth Keckley, also helped to change her views on slavery.

Mary was with her husband at the Ford Theatre when he was murdered by John Wilkes Booth on 14th April, 1865. This event had a detrimental impact on her mental state and she suffered frequent bouts of deep depression.

The situation became worse in 1867 when William Herndon wrote a book claiming that Lincoln had told him that Ann Rutledge, and not Mary, had been the love of his life. She responded by commenting: "This is the return for all my husband's kindness to this miserable man! Out of pity he took him into his office, when he was almost a hopeless inebriate and he was only a drudge, in the place."

Deeply upset by Herndon's revelation, Mary and her young son, Thomas Lincoln, moved to Germany. However, the poor health of her son forced her to return to the United States. Soon afterwards, Thomas died of tuberculosis.

Mary continue to worry unnecessarily about money. Charles Sumner had persuaded Congress to grant her a $3000 a year pension. She also had received a large percentage of her husband's estate. However, her conviction that she was poor, resulting in strange and irrational behaviour. This included selling her clothes and writing letters begging money from prominent politicians. In 1875 her only surviving son, Robert Lincoln, arranged for a sanity hearing. The court judged her insane and she was committed to a sanatorium in Batavia, Illinois.

On 15th June, 1876, a second trial judged Mary sane and she went to live with her sister in Springfield. Her health continued to deteriorate and she refused to leave her bedroom.

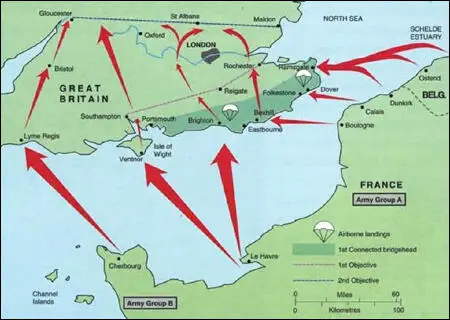

On this day in 1940 Adolf Hitler launched Operation Sea Lion the plan the invasion of Britain. The objective was to land 160,000 German soldiers along a forty-mile coastal stretch of south-east England. "As England, despite her hopeless military situation, still shows no sign of willingness to come to terms, I have decided to prepare, and if necessary to carry out, a landing operation against her. The aim of this operation is to eliminate the English motherland as a base from which war against Germany can be continued and, if necessary, to occupy completely."

General Kurt Student, the highest-ranking member of Germany's parachute infantry, had a meeting with Hitler: "At first Hitler developed in detail his general views, political and strategical, about how to continue the war against his principal enemy... He (Hitler) had not wished to provoke the British, as he hoped to arrange peace talks. But as they were unwilling to discuss things, they must face the alternative. Then a discussion followed about the use of the 11th Air Corps in an invasion of Great Britain. In this respect I expressed my doubts about using the Corps directly on the South coast, to form a bridgehead for the Army - as the area immediately behind the coast was now covered with obstacles.... He then pointed to Plymouth and dwelt on the importance of this great harbour for the Germans and for the English. Now I could no longer follow his thought, and I asked at what points on the south coast the landing was to take place." Hitler replied that operations were to be kept secret, and said: "I cannot tell you yet."

Hitler finally gave the order to land on a broad front from the Kent coast to Lyme Bay. Admiral Erich Raeder, the German naval commander-in-chief, declared that he could support only a narrow landing around Beachy Head and demanded air superiority even for this. The generals agreed to this, though they regarded Raeder's plan as a recipe for disaster and still accumulated forces for a landing in Lyme Bay. Hitler gave an assurance that the proposed landing would take place only when air attacks had worn down the British defences.

Within a few weeks the Germans had assembled a large armada of vessels, including 2,000 barges in German, Belgian and French harbours. Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt was put in charge of the operation: "As the first steps to prepare for an invasion were taken only after the French capitulation, no definite date could be fixed when the plan was drafted. It depended on the time required to provide the shipping, to alter ships so they could carry tanks, and to train the troops in embarking and disembarking. The invasion was to be made in August if possible, and September at the latest."

Hitler's generals were very worried about the damage that the Royal Air Force could inflict on the German Army during the invasion. Hitler therefore agreed to their request that the invasion should be postponed until the British airforce had been destroyed. On 1st August, 1940, Hitler ordered: "The Luftwaffe will use all the forces at its disposal to destroy the British air force as quickly as possible. August 5th is the first day on which this intensified air war may begin, but the exact date is to be left to the Luftwaffe and will depend on how soon its preparations are complete, and on the weather situation."

William Joyce (Lord Haw-Haw) told his British listeners: "I make no apology for saying again that invasion is certainly coming soon, but what I want to impress upon you is that while you must feverishly take every conceivable precaution, nothing that you or the government can do is really of the slightest use. Don't be deceived by this lull before the storm, because, although there is still the chance of peace, Hitler is aware of the political and economic confusion in England, and is only waiting for the right moment. Then, when his moment comes, he will strike, and strike hard."

Hitler instructed that there was to be no "terror bombing" of civilian targets but otherwise gave no direction to the campaign. On the 12th August the German airforce began its mass bomber attacks on British radar stations, aircraft factories and fighter airfields. During these raids radar stations and airfields were badly damaged and twenty-two RAF planes were destroyed. This attack was followed by daily raids on Britain. This was the beginning of what became known as the Battle of Britain.

Hitler told Admiral Erich Raeder that: "The invasion of Britain is an exceptionally daring undertaking, because even if the way is short this is not just a river crossing, but the crossing of a sea which is dominated by the enemy... For the Army forty divisions will be required; the most difficult part will be the continued reinforcement of military stores. We cannot count on supplies of any kind being available to us in England. The prerequisites are complete mastery of the air, the operational use of powerful artillery in the Straits of Dover and protection by minefields. The time of the year is an important factor too. The main operation will therefore have to be completed by 15 September... If it is not certain that preparations can be completed by the beginning of September, other plans must be considered." In October, 1940, Hitler issued orders that preparations for Sea Lion were to be limited to sustaining diplomatic and military pressure on Britain.

Operation Sea Lion was finally cancelled in January 1941. Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt later recalled: "The military reasons for its cancellation were various. The German Navy would have had to control the North Sea as well as the Channel, and was not strong enough to do so. The German Air Force was not sufficient to protect the sea crossing on its own. While the leading part of the forces might have landed, there was the danger that they might be cut off from supplies and reinforcements."