On this day on 11th September

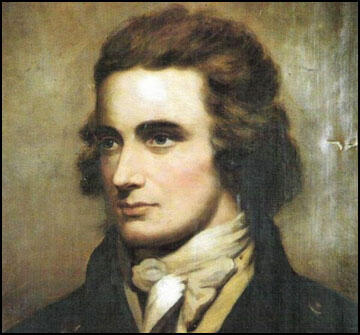

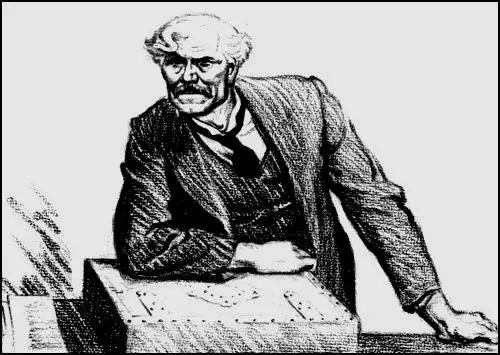

On this day in 1771 Mungo Park, the seventh of the thirteen children of Mungo Park (1714–1793) and Elspeth Hislop (1742–1817), was born at Foulshiels. His father was a prosperous tenant farmer. Park was educated at home by a tutor, and then at Selkirk Grammar School.

In 1785 he was apprenticed to Thomas Anderson, a surgeon in Selkirk, and in 1788 entered Edinburgh University to study medicine. According to his biographer, Christopher Fyfe: "He (Park) took more interest in botany than medicine, and in 1792 went to London where his brother-in-law, James Dickson, a seedsman, had made himself a well-known botanist." Dickson introduced Park to Joseph Banks, a patron of botanical research. The following year Banks sent him to Sumatra to collect botanical specimens.

On his return Banks arranged for Park to lead an African Association expedition to Gambia. Park later explained: "I had a passionate desire to examine into the productions of a country so little known, and to become experimentally acquainted with the modes of life and character of the natives. I knew that I was able to bear fatigue, and I relied on my youth, and the strength of my constitution, to preserve me from the effects of the climate. The salary which the committee allowed was sufficiently large, and I made no stipulation for future reward. If I should perish in my journey, I was willing that my hopes and expectations should perish with me; and if I should succeed in rendering the geography of Africa more familiar to my countrymen, and in opening to their ambition and industry new sources of wealth, and new channels of commerce."

Park left for Africa on 22nd May 1795. He arrived in Pisania on the Gambia River in July. Soon after arriving he developed malaria and he spent the next five months in the house of Dr John Laidley, a long-established slave-trader. After his recovery, accompanied by two slaves, Park began to explore the area. He encountered the Mandingo tribe that were part of the Mali Empire. "The Mandingoes, generally speaking, are of a mild, sociable, and obliging disposition. The men are commonly above the middle size, well shaped, strong, and capable of enduring great labour; the women are good-natured, sprightly, and agreeable. The dress of both sexes is composed of cotton cloth, of their own manufacture; that of the men is a loose frock, not unlike a surplice, with drawers which reach half way down the leg; and they wear sandals on their feet, and white cotton caps on their heads. The women's dress consists of two pieces of cloth, each of which they wrap round the waist, which, hanging down to the ankles, answers the purpose of a petticoat: the other is thrown negligently over the bosom and shoulders."

Most of the people he encountered were slaves: "I suppose, not more than one-fourth part of the inhabitants at large; the other three-fourths are in a state of hopeless and hereditary slavery; and are employed in cultivating the land, in the care of cattle, and in servile offices of all kinds, much in the same manner as the slaves in the West Indies. I was told, however, that the Mandingo master can neither deprive his slave of life, nor sell him to a stranger, without first calling a palaver on his conduct; or, in other words, bringing him to a public trial; but this degree of protection is extended only to the native of domestic slave. Captives taken in war, and those unfortunate victims who are condemned to slavery for crimes or insolvency, and, in short, all those unhappy people who are brought down from the interior countries for sale, have no security whatever, but may be treated and disposed of in all respects as the owner thinks proper. It sometimes happens, indeed, when no ships are on the coast, that a humane and considerate master incorporates his purchased slaves among his domestics; and their offspring at least, if not the parents, become entitled to all the privileges of the native class."

Mungo Park commented in his journal: "And although the African mode of living was at first unpleasant to me, yet I found, at length, that custom surmounted trifling inconveniences, and made everything palatable and easy." By the end of the year Park had covered over 300 miles, and reached the Bambara state of Kaarta. Soon afterwards he was captured by the Moors. He was held for three months before being allowed to continue his journey.

Park, who had lost his two slaves, continued his search for the Niger River. He eventually reached it at Ségou. He wrote in his journal: "I saw with infinite pleasure the great object of my mission; the long sought for majestic Niger, glittering to the morning sun, as broad as the Thames at Westminster, and flowing slowly to the eastward". However, the ruler denied him entry to his city. After reaching Bamako he turned west. Severely ill with fever, he struggled on to Kamalia where he found a friendly Muslim trader, Karfa Taura, who agreed to look after him.

On 10 June 1797 Park and Taura reached Pisania. The explorer recorded in his journal that this was a slave-trading area: "The slaves are commonly secured by putting the right leg of one, and the left of another into the same pair of fetters. By supporting the fetters with string they can walk very slowly. Every four slaves are likewise fastened together by the necks. They were led out in their fetters every morning to the shade of the tamarind tree where they were encouraged to sing diverting songs to keep up their spirits; for although some of them sustained the hardships of their situation with amazing fortitude, the greater part were very much dejected, and would sit all day in the sort of sullen melancholy with their eyes fixed upon the ground."

Park joined an American slave ship, Charlestown bound for South Carolina. He later recalled the journal: "The number of slaves received on board this vessel... was one hundred and thirty; of whom about twenty-five had been, I suppose, of free condition in Africa, as most of them, being Bushreens, could write a little Arabic. Nine of them had become captives in the religious war between Abdulkader and Damel.... My conversation with them, in their native language, gave them great comfort; and as the surgeon was dead, I consented to act in a medical capacity in his room for the remainder of the voyage. They had in truth need of every consolation in my power to bestow; not that I observed any wanton acts of cruelty practised either by the master or the seamen towards them; but the mode of confining and securing Negroes in the American slave ships, owing chiefly to the weakness of their crews, being abundantly more rigid and severe than in British vessels employed in the same traffic, made these poor creatures to suffer greatly, and a general sickness prevailed amongst them. Besides the three who died on the Gambia, and six or eight while we remained at Goree, eleven perished at sea, and many of the survivors were reduced to a very weak and emaciated condition."

He eventually arrived back to England after an absence of two years, seven months. Park was able to provide the African Association with a detailed map of the area that he explored. Mungo Park's book, Travels to the Interiors of Africa, was published in 1799. It was a best-seller with three editions published during the first year. His biographer, Christopher Fyfe, has pointed out: "Written in a straightforward, unpretentious, narrative style, it gave readers their first realistic description of everyday life in west Africa, depicted without the censorious, patronizing contempt which so often has disfigured European accounts of Africa... "

Although Park had himself not advocated an end to slavery, the anti-slavery movement, did make full use of its descriptions of the trade in the book. As Hugh Thomas has pointed out in his book, The Slave Trade (1997), from the figures provided by Park, "probably slaves had constituted three-quarters of West African exports in the eighteenth century."

Park married Allison Anderson on 2nd August 1799 and practised as a doctor in Peebles. He longed for a chance to return to Africa and in 1804 he was chosen to take a party along the Niger River. The objective was "to the utmost possible distance to which it can be traced". He was commissioned as a captain with a salary of £5,000, and £1,000 for his brother-in-law, Alexander Anderson, who went with him.

Park reached Goree in Senegal in March 1805. The following month his party, that included Lieutenant John Martyn, thirty-five soldiers and six other men, left for the Gambia, where Park recruited Isaaco, as their guide, and then set off for the interior. Travelling with so large a party, their baggage loaded on donkeys, was slow work. They also suffered from various diseases and by the time they reached Bamako, thirty-one of the party were dead. Park himself only just survived a severe case of dysentery.

Mungo Park and his remaining men now travelled to Sansanding where they sold off their surplus goods in the market to raise money to construct a boat to take them down the river. The men then began building a 40 foot, flat-bottomed sailing boat, rigged to sail with any wind. During this period Alexander Anderson died. By the time the party left, only Park, Martyn and three soldiers were left to travel down the river.

In January 1806 they reached Yelwa in the Hausa country (modern Nigeria), some 1500 miles from Sansanding. Soon afterwards they were attacked from the shore. In the subsequent conflict Park, Martyn, and the soldiers were killed.

On this day in 1871 Inez Bensusan, the daughter of mining agent, Samuel Levy Bensusan, was born in Sydney, into a wealthy Jewish family.She worked as an actress in Australia before moving to London in about 1893 where she became involved in the struggle for women's suffrage.

Bensusan became a member of the Women's Social and Political Union and in 1908 she joined with Elizabeth Robins, Kitty Marion, Winifred Mayo, Sime Seruya, Edith Craig, Ellen Terry, Lillah McCarthy, Sybil Thorndike, Lena Ashwell, Lily Langtry and Nina Boucicault to establish the Actresses' Franchise League.

The first meeting of the AFL took place at the Criterion Restaurant at Piccadilly Circus. The AFL was open to anyone involved in the theatrical profession and its aim was to work for women's enfranchisement by educational methods, selling suffrage literature and staging propaganda plays. The AFL neither supported nor condemned militancy.

Inez Bensusan oversaw the writing, collection and publication of Actresses' Franchise League plays. Pro-suffragette plays written by members of the Women Writers Suffrage League and performed by the Actresses' Franchise League included How the Vote was Won and A Pageant of Great Women (Cicely Hamilton) and Votes for Women (Elizabeth Robins).

Bensusan's first play, The Apple, was performed as part of a weekend protest organised by the WSPU against the Census in April 1911. The following year Bensusan wrote The Womanhood, in which she played the principal character. Bensusan was also the author of Nobody's Sweetheart (1911) and the suffrage film True Womanhood.

Bensusan helped form the Jewish League for Woman Suffrage in 1912. She joined the executive committee of the organisation whose main objective was "to demand the Parliamentary Franchise for women, on the same terms as it is, or may be, granted to men." One member wrote that "it was felt by a great number that a Jewish League should be formed to unite Jewish Suffragists of all shades of opinions, and that many would join a Jewish League where, otherwise, they would hesitate to join a purely political society."

In December 1913 she established the Women's Theatre Company, at the Coronet Theatre. The main objective of the organization was "to widen the sphere of propaganda still further by establishing a permanent season for the presentation of dramatic works dealing with the Women's Movement." According to Elizabeth Crawford, the author of The Suffragette Movement (1999): "It's first, and only, season was a success; its second was pre-empted by the outbreak of war."

During the First World War she took the Women's Theatre Company overseas to entertain the troops. She also appeared in two films, The Grit of a Jew (1917) and Adam Bede (1918). She stayed there for three and half years, appearing in fifty plays for the British Rhine Army Dramatic Company at the Deutsches Theatre, Bismarckstrasse.

Bensusan continued to act and had a major success in The Matriarch by Gladys Bronwyn Stern, which ran at the Royalty Theatre for 229 performances in 1929 and toured America in 1930. The play centers around two characters, the matriarch Anastasia and her granddaughter, Toni.

Bensusan also remained actively involved with the Actresses' Franchise League. After the war she co-founded the House of Arts in Chiswick to encourage local theatre, music, and art and appeared in a House of Arts drama circle triple bill in Chiswick Town Hall in 1951.

Inez Bensusan died at 49 Eaton Road, Sutton, Surrey, on 10th October 1967.

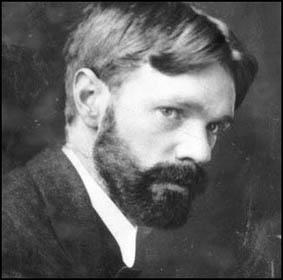

On this day in 1885 David Herbert Lawrence, the fourth of the five children of Arthur John Lawrence (1846–1924), a miner, was born in Eastwood near Nottingham. His father was barely literate, but his mother, Lydia Lawrence, was better educated and was determined that David and his brothers should not become miners.

According to his biographer, John Worthen: "Arthur Lawrence, like his three brothers, was a coalminer who worked from the age of ten until he was sixty-six, was very much at home in the small mining town, and was widely regarded as an excellent workman and cheerful companion. Lawrence's mother Lydia was the second daughter of Robert Beardsall and his wife, Lydia Newton of Sneinton; originally lower middle-class, the Beardsalls had suffered financial disaster in the 1860s and Lydia, in spite of attempts to work as a pupil teacher, had, like her sisters, been forced into employment as a sweated home worker in the lace industry. But she had had more education than her husband, and passed on to her children an enduring love of books, a religious faith, and a commitment to self-improvement, as well as a profound desire to move out of the working class in which she felt herself trapped."

As a child Lawrence preferred the company of girls to boys and this led to him being bullied at school. He was an intelligent boy and at the age of 12 he became the first boy from Eastwood to win one of the recently established county council scholarships, and went to Nottingham High School. However, he did not get on with the other boys and left school in the summer of 1901 without qualifications.

Lawrence started work as a factory clerk for a surgical appliances manufacturer in Nottingham. Soon afterwards, his eldest brother, William Ernest Lawrence, by now a successful clerk in London, fell ill and died on 11th October 1901. Lydia Lawrence was distraught with the loss of her favourite son and now turned her attention to the career of David. John Worthen argues that "she needed her children to make up for the disappointments of her life." David now gave up his employment as a clerk and started work as a pupil teacher at the school in Eastwood for miner's children.

Lawrence became friendly with Jessie Chambers. Her sister, Ann Chambers Howard, has argued: "They spent a great deal of time together working and reading, walking through the fields and woods, talking and discussing. Jessie was interested in everything, to such a degree that her intensity of perception almost amounted to a form of worship. She felt that her own appreciation of beauty, of poetry, of people, and of her own sorrows amounted to something far greater than anyone else had ever experienced. Her depth of felling was a great stimulation to Lawrence, who with his naturally sensitive mind was roused to critical and creative consciousness by her." Together they developed an interest in literature. This included reading books together and discussing authors and writing. It was under Jessie's influence that in 1905 Lawrence started to write poetry. Lawrence later admitted that Jessie was "the anvil on which I hammered myself out." The following year he began work on his first novel, The White Peacock.

Lawrence's mother wanted him to continue his education and in 1906 he began studying for his teacher's certificate at the University College of Nottingham. In 1908 Lawrence qualified as a teacher and found employment at Davidson Road School in Croydon. According to the author of D. H. Lawrence: The Life of an Outsider (2005): "He found the demands of teaching in a large school in a poor area very different from those at Eastwood under a protective headmaster. Nevertheless he established himself as an energetic teacher, ready to use new teaching methods (Shakespeare lessons became practical drama classes, for example)."

In 1909 Jessie Chambers sent some of Lawrence's poems to Ford Madox Ford, the editor of The English Review. Ford was greatly impressed with the poems and arranged a meeting with Lawrence. After reading the manuscript of The White Peacock, wrote to the publisher William Heinemann recommending it. Ford also encouraged Lawrence to write about his mining background.

While living in Croydon Lawrence became friendly with a fellow schoolteacher, Helen Corke, who had recently had an affair with a married man who killed himself. She told Lawrence the story, and showed him her manuscript, The Freshwater Diary. Lawrence used this material for his next novel, The Trespasser.

Lawrence also began work on the autobiographical novel, Sons and Lovers. He sent the first-drafts of the novel to Jessie Chambers. As her sister, Ann Chambers Howard points out: "The ruthless streak in his nature now began to emerge and halfway through the book Jessie became increasingly alarmed and bewildered by his cruel treatment of people whom they knew. He began to include people, episodes and attitudes which were quite foreign to their nature and to their previous behaviour and experience.... My father remembered watching her as she read the manuscripts, writing her comments carefully at the side before sending them back to him. Lawrence rejected her advice completely, insisting on including all the things which she had begged him to alter or omit. He continued to send her the manuscripts, asking for advice which she in her anguish repeatedly gave, only to be continually ignored." Eventually she refused to answer Lawrence's letters and their relationship came to an end.

In August 1910, Lydia Lawrence became ill with cancer. Lawrence visited his mother in Eastwood every other weekend. In October he realised she was close to death and he decided to stay at home to nurse her. He wrote to a friend: "There has been this kind of bond between me and my mother... We knew each other by instinct... We have been like one, so sensitive to each other that we never needed words. It has been rather terrible and has made me, in some respects, abnormal." His mother died on 9th December 1910. Soon afterwards Lawrence had got engaged to his old college friend Louie Burrows.

In January 1911, Lawrence's first novel, The White Peacock, was published. However, his writing was not going well. Without the advice of Jessie Chambers, he found it difficult to continue with Sons and Lovers. His health was poor and after falling seriously ill with pneumonia he decided to abandon his teaching career. After convalescence in Bournemouth, he rewrote The Trespasser.

Lawrence broke off his engagement to Louie Burrows, and returned to Nottingham. On 3rd March 1912, Lawrence went to see Ernest Weekley, who taught him while he was at the University College of Nottingham. During the visit he met his much younger wife, Frieda von Richthofen. Lawrence fell in love with Frieda and in May 1912 managed to persuade her to leave her husband and three young children. However, as John Worthen has pointed out: "Frieda's desire to be free of her marriage was not consistent with Lawrence's insistence that she become his partner, and she suffered agonies from the loss of her children (Weekley was determined to keep them away from her)."

Claire Tomalin has argued: "She (Frieda) gave him what he most wanted at the time they met, being probably the first woman who positively wanted to go to bed with him without guilt or inhibition; she was not only older, and married, but bored with her husband, and had been encouraged to believe in the therapeutic power of sex by an earlier lover, one of Freud's disciples. Lawrence was bowled over by this... Whether her decision to throw in her lot permanently with Lawrence contributed positively to his development as a writer is at least open to question. There could have been a different story, in which Lawrence married someone like the intelligent Louie; in which he settled in England and lived a quiet, healthy - and longer - life, cherished by his wife and family; in which his novels continued more in the pattern of Sons and Lovers and The Rainbow, social and psychological studies of the country and people he knew best."

Lawrence set-up home with Frieda in Icking, near Munich. Lawrence claimed "the one possible woman for me, for I must have opposition - something to fight". The author of D. H. Lawrence: The Life of an Outsider has argued: "He cooked, cleaned, wrote, argued; Frieda attended little to house keeping (though washing became her specialty), but she could always hold her own against his theorizing, and maintained her independence of outlook as well as of sexual inclination (she slept with a number of other men during her time with Lawrence)." While living in Germany he finished his autobiographical novel Sons and Lovers. His publisher, Heinemann turned down the novel on grounds of indecency. He sent it to his friend, Edward Garnett, who read manuscripts for Gerald Duckworth and Company. The novel was accepted and published in May 1913. It received some good reviews but sold poorly.

In 1914 the couple returned to England. Lawrence's novel brought him to the attention of Edward Marsh. He introduced Lawrence to Katherine Mansfield and John Middleton Murry. They were witnesses to Lawrence's marriage to Frieda. Claire Tomalin has pointed out: "The men put on formal three-piece suits, Frieda enveloped herself in flowing silks and Katherine wore a sombre suit." Lawrence wrote to a friend: "I don't feel a changed man, but I suppose I am one."

The two couples established themselves in two cottages near Chesham in Buckinghamshire. Later, Mansfield and Murry joined the Lawrences at Higher Tregerthen, near Zennor, in an attempt at communal living. It was a failure and within weeks she and Murry moved on.

On the outbreak of the First World War the authorities became concerned that Frieda von Richthofen was a spy. Local people reported that the Lawrences were using the clothes hanging on their washing line to send coded messages to German U-boats. After searching their cottage, the authorities forced the Lawrences to leave the area.

Lawrence began spending time with Philip Morrell and Ottoline Morrell at their home Garsington Manor near Oxford. It was also a refuge for conscientious objectors. They worked on the property's farm as a way of escaping prosecution. It also became a meeting place for a group of intellectuals described as the Bloomsbury Group. Members included Virginia Woolf, Vanessa Bell, Clive Bell, John Maynard Keynes, David Garnett, E. M. Forster, Duncan Grant, Lytton Strachey, Dora Carrington, Gerald Brenan, Ralph Partridge, Bertram Russell, Leonard Woolf, Desmond MacCarthy and Arthur Waley. Other people who Lawrence met at Garsington included Dorothy Brett, Mark Gertler, Siegfried Sassoon, Aldous Huxley, Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson, Thomas Hardy, Vita Sackville-West, Harold Nicolson and T.S. Eliot.

The Rainbow was published in September 1915. According to Claire Tomalin: "Katherine Mansfield's reminiscences of New Zealand probably inspired Lawrence with the lesbian episode in The Rainbow, and she was certainly the model for Gudrun in Women in Love." It received hostile reviews that concentrated on the way Lawrence dealt with sexual themes. Robert Wilson Lynd in The Daily News said the book was "windy, tedious, boring and nauseating". Lynd, and another critic, Clement King Shorter, condemned the lesbian episode in the book. Another reviewer argued that the book "betrayed the young men" fighting on the Western Front.

At Bow Street Magistrates' Court on 13th November the novel was banned as obscene. As John Worthen has pointed out: "Its religious language, emotional and sexual explorations of experience, and sheer length had given its readers problems, but it was Ursula's lesbian encounter with a schoolteacher in the chapter Shame which had finally condemned it in the eyes of the law and of a country now focused on conflict."

In the autumn of 1915 Lawrence had joined forces with Katherine Mansfield and John Middleton Murry to establish a new magazine called The Signature. Claire Tomalin, the author of Katherine Mansfield: A Secret Life (1987) has argued that it was decided "to sell by subscription; it was to be printed in the East End, and the contributors were to have a club room in Bloomsbury for regular meetings and discussions." Sales were poor and the magazine folded after three issues.

Ottoline Morrell helped Lawrence with his writing by supporting him emotionally and financially. In December 1916 he showed her his unpublished novel, Women in Love. On reading it she was extremely upset at the unflattering portrayal of herself that was thinly disguised in the character of Hermione Roddice. Philip Morrell went to Lawrence's agent and threatened to bring legal action against any publisher who brought out the book.

Lawrence, who was opposed to the war, was twice called up for military service but was rejected on health grounds. The couple went to live in a cottage at Pulborough. Later they were joined by John Middleton Murry when Katherine Mansfield suffering from tuberculosis, had moved to Bandol on the south coast of France.

Lawrence caught influenza during the pandemic in November 1918, and once again he nearly died. It was not until a year later that he was fit enough to leave England. At first he lived in Florence but after Frieda Lawrence joined him after her visit to her family in Germany, they settled temporarily in Picinisco, in the Abruzzi Mountains, before moving on to Capri, where the English writing colony, including Compton Mackenzie, W and Francis Brett Young. In February 1920, they moved to Sicily, where they stayed for the next two years.

In 1920 Martin Secker agreed to publish Women in Love, a sequel to his earlier novel The Rainbow, and follows the continuing loves and lives of the Brangwen sisters, Gudrun and Ursula. Once again the sexual content of the book caused controversy. over its sexual subject matter. W. Charles Pilley in the John Bull Magazine, said: "I do not claim to be a literary critic, but I know dirt when I smell it, and here is dirt in heaps - festering, putrid heaps which smell to high Heaven." Even his friend, John Middleton Murry, wrote in the The Athenaeum that Lawrence was "far gone in the maelstrom of his sexual obsession" and that the novel was "sub-human and bestial."

In January 1921 Lawrence and Frieda visited Sardinia and he wrote the travel book, Sea and Sardinia. He also completed his next book Aaron's Rod, a novel in which Aaron Sisson, is a union official in the coal mines, decides to leave his wife and family, and move to Florence, where he attempts to make a living as a musician. In order for it to be published, Martin Secker, heavily censored the passages describing Aaron's sexual experiences.

This time John Middleton Murry liked the book describing it as "the most important thing that has happened to English literature since the war". The author of D. H. Lawrence: The Life of an Outsider argues that "to most reviewers, however, it was simply another interesting book made rather unpleasant by Lawrence's obsession with sex." Richard Rees has argued: "If Lawrence was the one great original genius of English literature in my time, Murry was the one critic with the necessary combination of gifts for coping with him, and Lawrence was aware of this, off and on. In the process Murry sometimes made mistakes and sometimes made himself ridiculous. But how can anyone fail to see that this was inevitable in the circumstances?"

Over the next few months Lawrence's revised his short novels, The Fox, The Captain's Doll, and The Ladybird. He also wrote ten short stories with a First World War background that appeared in the collection, England, my England and Other Stories (1922). According to John Worthen the stories were "a way of coming to terms with the past, and putting it behind him".

In February 1922 Lawrence and Frieda decided to travel to Ceylon. He found the country too hot for writing and moved onto Australia. Settling at Thirroul, 69 km south of Sydney, Lawrence wrote his novel Kangaroo, in six weeks. The book tells the story of an English writer, Richard Lovat Somers, and his German wife Harriet. This appears to be semi-autobiographical and is based on the time he spent in New South Wales. "Kangaroo" is the nickname of one of Lawrence's characters, Benjamin Cooley, the leader of a secretive, fascist paramilitary organisation. It has been argued that Cooley was based on Major General Charles Rosenthal, a notable right wing activist in the early 1920s.

Lawrence and Frieda visited North America and while in Santa Fe, developed a close friendship with the poet, Witter Bynner and his lover, Willard Johnson. Bynner took the Lawrences to Taos in New Mexico to see a local Apache reservation. Lawrence also met Mabel Dodge Luhan and later these characters are portrayed in his novel The Plumed Serpent (1926).

Lawrence returned to England for a brief holiday and having invited his London friends to dinner at the Café Royal, he encouraged them to come back to New Mexico with him and Frieda where he was "committed to... establishing a new life on earth". Only John Middleton Murry and Dorothy Brett were the only ones to accept the offer. However, Middleton Murry changed his mind at the last moment. In March, 1924, the three left for North America and with the help of Mabel Dodge Luhan they established a small community at Taos.

In March 1925, D. H. Lawrence went down with a combination of typhoid and pneumonia, and nearly died. The doctor also diagnosed tuberculosis. Lawrence and Frieda had planned to return to England, but the doctor advised altitude, and they made their way back up to the ranch. Lawrence recorded that "New Mexico was the greatest experience from the outside world that I have ever had." However, for the sake of his health it was decided to move back to Italy. This time they stayed in Spotorno with Angelo Ravagli. Frieda's daughters also lived with them for a while. He used these experiences to write his short novel The Virgin and the Gipsy. Frieda began an affair with Ravagli, who later claimed that Lawrence discovered them "flagrante delicto". Lawrence's biographer argued that he responded by having an affair with Dorothy Brett while she was on holiday in Italy.

In 1926 he visited Nottingham. This inspired him to begin a new novel, Lady Chatterley's Lover. Lawrence's biographer, John Worthen, has argued: "His sympathy was now far more with his father (who had died in 1924) than with his mother, and the novel's central character was thoroughly working-class. The second version, started in November 1926, made the novel sexually explicit; it became a hymn to the love-making of the couple, to the body of the man and the woman, for sexuality as it could potentially be between an independent working-class man and an independent upper-class woman. It was a final fictional reworking of a theme which he had always written about for the chance it gave him to concentrate on sexual attraction (and to some extent had enacted in his own life and relationships), but which he now returned to both polemically and nostalgically."

The highly explicit sex passages in the book meant that Lawrence was unable to find a publisher for the novel. With the help of the Italian bookseller Pino Orioli, Lawrence arranged for Lady Chatterley's Lover to be printed in and distributed from Florence. The book made him so much money that he could now afford to live in expensive hotels. Later he moved to Bandol on the south coast of France.

Lawrence gave up writing fiction but he continued to write poems and newspaper articles. In 1929 the police seized the unexpurgated typescript of his volume of poems Pansies. An exhibition of his paintings in London that summer was raided by the police, and court hearings were necessary before the paintings could be returned to their owner.

In February 1930, D. H. Lawrence went into the Ad Astra Sanatorium in Vence, where he was visited by friends from England, including H. G. Wells and Aldous Huxley. He discharged himself from the sanatorium on 1st March, and Frieda Lawrence helped him move into the Villa Robermond, a rented house in the town. He died the following day and was buried in the local cemetery on 4th March.

Soon after his death, the novelist Ethel Mannin, wrote: "D. H. Lawrence turned his back in disgust on civilization as we know it and attempted to find uncorrupted life in the Mexican wildernesses. Since his death various little people have written patronizing little articles about him pointing to his limitations, regardless of the fact that in his limitations he was infinitely greater than any of them in their fulfilments. His preoccupation with sex was a preoccupation with life."

On this day in 1917 Jessica Mitford, the daughter of the 2nd Baron Redesdale, was born in Burford, Oxfordshire. The sister of Diana Mitford, Nancy Mitford and Unity Mitford, she was educated at home by her mother.

Mitford's parents held right-wing political views and supported the British Union of Fascists and in 1936 their daughter, Diana Mitford, married its leader, Oswald Mosley. Another daughter, Unity Mitford, went to Nazi Germany and became a close friend of Adolf Hitler.

Unlike the rest of her family, Jessica developed left-wing political opinions. At the age of fourteen she was converted to pacifism and later, like her sister, Nancy Mitford, became a socialist. Jessica even considered the possibility of visiting Germany with her sister and murdering Hitler. She later wrote: "Unfortunately, my will to live was too strong for me actually to carry out this scheme, which would have been fully practical and might have changed the course of history. Years later, when the horrifying history of Hitler and his regime had been completely unfolded, leaving Europe half-destroyed, I often bitterly regretted my lack of courage."

In 1937 Mitford met Esmond Romilly, the nephew of Winston Churchill, who had just returned to England after fighting for the International Brigades in the Spanish Civil War. He was now working as a journalist for the News Chronicle and was about to go back to Spain to report on the war. Jessica went with him and they married in June 1937. While on honeymoon he wrote Boadilla , an account of his experiences in Spain.

When the couple returned to England Esmond Romilly found work as a copywriter for a small advertising agency in London, whereas Jessica was employed in market research. Along with her husband she became involved in the struggle against the British Union of Fascists.

In 1939 Mitford and Romilly went to the United States. On the outbreak of the Second World War Romilly joined the Royal Canadian Air Force but was killed in 1941 during a bombing raid over Nazi Germany.

Mitford went to work for Office of Price Administration (OPA) where she met the radical lawyer, Robert Treuhaft, who she married in 1943. They both joined the American Communist Party and were active in the Civil Rights movement.

In 1948 they moved to Oakland and Treuhaft joined the legal firm of Oakland, Grossman, Sawyer & Edises. The company specialized in trade union and civil rights cases. This included the Willie McGee case. McGee, a 36-year-old black truck driver from Laurel, Mississippi, was convicted of raping a white woman despite evidence that the couple had been having a relationship for four years. The trial lasted less than a day and the jury took under three minutes to reach a verdict and the judge sentenced McGee to be executed. McGee's defenders argued that no white man had ever been condemned to death for rape in the deep South, while over the last forty years 51 blacks had been executed for this offence.

Mitford travelled to Mississippi to organize a campaign against the sentence. While there she reported on the case for The Peoples World. This included an interview with William Faulkner who spoke out against the decision to execute McGee. Despite a nationwide campaign led by Bella Abzug and William Patterson, McGee was executed on 8th May 1951.

Mitford's involvement in the Willie McGee case resulted in her being subpoenaed by the California State Committee on Un-American Activities. Mitford and her husband, Robert Treuhaft, took the 1st Amendment and refused to answer questions about their involvement in left-wing political groups. Two years later they were called before the Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). Once again they refused to give evidence and later Treuhaft was described by Joseph McCarthy as one if the most subversive lawyers in the country.

Over the next few years Mitford became increasingly disillusioned with the form of communism being developed in the Soviet Union. This despair grew with the revelations about Joseph Stalin by Nikita Khrushchev and the Red Army invasion of Hungary. Treuhaft and Mitford finally left the American Communist Party in 1958 after John Gates was ousted as editor of the Daily Worker.

As a trade union lawyer Treuhaft became aware of the financial problems that deaths caused in working class families. In an attempt to reduce the high costs of funerals he established the Bay Area Funeral Society, a non-profit undertaking service. In 1963 Treuhaft and Mitford published the best-selling book, The American Way of Death (1963). However, only Mitford's name appeared on the book cover as the publisher argued that "co-signed books never sell as well as those with one author."

Other books by Mitford included the autobiography, Hons and Rebels (1960), The Trial of Dr. Spock (1970), A Fine Old Conflict (1977), an account of her time in the American Communist Party, and The Making of a Muckraker (1979).

Jessica Mitford died in 1996.

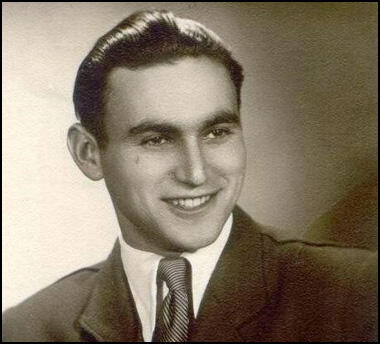

On this day in 1924 war hero Rudolf Vrba (Walter Rosenberg), the son of a sawmill owner, was born in Slovakia. At the age of fifteen he was expelled from his high school in Bratislava, under the Slovak puppet state's version of the Nazis' Nuremberg Laws.

After the outbreak of the Second World War, Vrba, like other Jews in countries occupied in Nazi Germany, was rounded up and sent to concentration camps. In 1942 Vrba arrived in Auschwitz. On 9th April 1944, Vrba and his friend, Alfred Wetzler, managed to escape. The two men spent eleven days walking and hiding before they got back to Slovakia.

Vrba and Wetzler made contact with the local Jewish Council. They provided details of the Holocaust that was taking place in Eastern Europe. They also gave an estimate of the number of Jews killed in Auschwitz between June 1942 and April 1944: about 1.75 million. In June, 1944, the 32-page Vrba-Wetzler Report was published. It was the first information about the extermination camps to reach the free world and to be accepted as credible.

In September 1944 Vrba joined the Czechoslovak partisans and was later decorated for bravery. After the war he read biology and chemistry at Charles University, Prague, took a doctorate and then escaped to the west. He worked in Israel from 1958 to 1960 at the biological research institute in Beit Dagan. He then moved to Britain and worked for the Medical Research Council.

Vrba's memoirs, I Cannot Forgive, appeared in 1963. They were later republished as I Escaped from Auschwitz. In 1967 Vrba became professor of biochemistry in the pharmacology department of the medical school of the University of British Columbia (UBC) in Canada.

Rudolf Vrba died of cancer on 26th March, 2006.

On this day in 1924 the Daily Mail makes corruption allegations against Ramsay MacDonald. In April 1924, MacDonald recommended Alexander Grant, the managing director of McVitie and Price, for a baronetcy. This was a surprise as Grant was a lifelong supporter of the Conservative Party. On 11th September, 1924, the Daily Mail reported that Grant had given MacDonald a Daimler car and was the holder of £30,000 worth of shares in McVitie and Price. MacDonald replied that the shares simply covered the running of the car. This was hardly convincing and the story caused considerable embarrassment to the Labour government. He eventually agreed to give the car back to the company.

On this day in 1941 Charles Lindbergh makes a controversial speech in Des Moines

"The three most important groups who have been pressing this country toward war are the British, the Jewish and the Roosevelt administration. Behind these groups, but of lesser importance, are a number of capitalists, Anglophiles and intellectuals who believe that their future, and the future of mankind, depends upon the domination of the British Empire... These war agitators comprise only a small minority of our people; but they control a tremendous influence... It is not difficult to understand why Jewish people desire the overthrow of Nazi Germany... But no person of honesty and vision can look on their pro-war policy here today without seeing the dangers involved in such a policy, both for us and for them. Instead of agitating for war, the Jewish groups in this country should be opposing it in every possible way, for they will be among the first to feel its consequences....

I am not attacking either the Jewish or the British people. Both races, I admire. But I am saying that the leaders of both the British and the Jewish races, for reasons which are as understandable from their viewpoint as they are inadvisable from ours, for reasons which are not American, wish to involve us in the war. We cannot blame them for looking out for what they believe to be their own interests, but we also must look out for ours. We cannot allow the natural passions and prejudices of other peoples to lead our country to destruction."

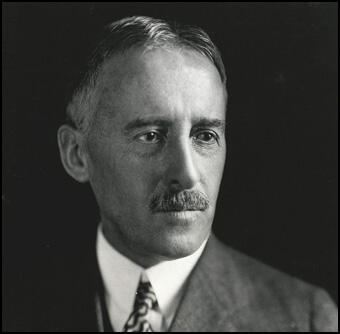

On this day in 1945 Henry Stimson, Secretary of War, warns President Harry S. Truman of the dangers of atomic weapons.

"The chief lesson I have learned in a long life is that the only way you can make a man trustworthy is to trust him; and the surest way to make him untrustworthy is to distrust him. If the atomic bomb were merely another, though more devastating, military weapon to be assimilated into our pattern of international relations, it would be one thing. We would then follow the old custom of secrecy and nationalistic military superiority relying on international caution to prescribe the future use of the weapon as we did with gas. But I think the bomb instead constitutes merely a first step in a new control by man over the forces of nature too revolutionary and dangerous to fit into old concepts. My idea of an approach to the Soviets would be a direct proposal after discussion with the British that we would be prepared in effect to enter an agreement with the Russians, the general purpose of which would be to control and limit the use of the atomic bomb as an instrument of war."

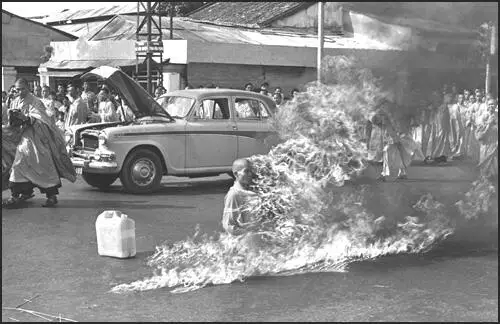

On this day in 1963 it is reported in the New York Times that Thich Quang Due has set fire to himself in protest against the Vietnam War.

"On June 11, an aged Buddhist priest, Thich Quang Due, sat down at a major intersection, poured gasoline on himself, took the cross-legged 'Buddha' posture and struck a match. He burned to death without moving and without saying a word. Thich Quang Due became a hero to the Buddhists in Vietnam, and he dramatized their cause for the rest of the world."