On this day on 3rd August

On this day in 1792 Richard Arkwright died aged 59 on 3rd August 1792 at his home in Cromford, after a month's illness. On 10th August, over 2,000 by two people attended his funeral. The Gentleman's Magazine claimed that on his death, Arkwright was worth over £500,000 (over £200 million in today's money).

Richard Arkwright, the sixth of the seven children of Thomas Arkwright (1691–1753), a tailor, and his wife, Ellen Hodgkinson (1693–1778), was born in Preston on 23rd December, 1732. Richard's parents were very poor and could not afford to send him to school and instead arranged for him to be taught to read and write by his cousin Ellen.

Richard became a barber's apprentice at Kirkham before moving to Bolton. He worked for Edward Pollit and in 1754 he started his own business as a wig-maker. The following year he married Patience Holt, the daughter of a schoolmaster. Their only child, Richard Arkwright, was born on 19th December 1755. After the death of his first wife he married Margaret Biggins (1723–1811) on 24th March 1761.

Arkwright's work involved him travelling the country collecting people's discarded hair. In September 1767 Arkwright met John Kay, a clockmaker, from Warrington, who had been busy for some time trying to produce a new spinning-machine with another man, Thomas Highs of Leigh. Kay and Highs had run out of money and had been forced to abandon the project. Arkwright was impressed by Kay and offered to employ him to make this new machine.

Arkwright also recruited other local craftsman, including Peter Atherton, to help Kay in his experiments. According to one source: "They rented a room in a secluded teacher's house behind some gooseberry bushes, but they were so secretive that the neighbours were suspicious and accused them of sorcery, and two old women complained that the humming noises they heard at night must be the devil tuning his bagpipes."

As the economic historian, Thomas Southcliffe Ashton, has pointed out, Arkwright did not have any great inventive ability, but "had the force of character and robust sense that are traditionally associated with his native county - with little, it may be added, of the kindliness and humour that are, in fact, the dominant traits of Lancashire people."

In 1768 the team produced the Spinning-Frame and a patent for the new machine was granted in 1769. The machine involved three sets of paired rollers that turned at different speeds. While these rollers produced yarn of the correct thickness, a set of spindles twisted the fibres firmly together. The machine was able to produce a thread that was far stronger than that made by the Spinning-Jenny produced by James Hargreaves.

Adam Hart-Davis has explained the way the new machine worked: "Several spinning machines were designed at about this time, but most of them tried to do the stretching and the spinning together. The problem is that the moment you start twisting the roving you lock the fibres together. Arkwright's idea was to stretch first and then twist. The roving passed from a bobbin between a pair of rollers, and then a couple of inches later between another pair that were rotating at twice the speed. The result was to stretch the roving to twice its original length. A third pair of rollers repeated the process... Two things are obvious the moment you see the wonderful beast in action. First, there are 32 bobbins along each side of each end of the water frame - 128 on the whole machine. Second, it is so automatic that even I could operate it."

On 29th September 1769 Arkwright rented premises in Nottingham. However, he had difficulty finding investors in his new company. David Thornley, a merchant, of Liverpool, and John Smalley, a publican from Preston, did provide some money but he still needed more to start production. Arkwright approached a banker Ichabod Wright but he rejected the proposal because he judged that there was "little prospect of the discovery being brought into a practical state".

Wright introduced Arkwright to Jedediah Strutt and Samuel Need. Strutt was a manufacturer of stockings and the inventor of a machine for the machine-knitting of ribbed stockings. Strutt and Need were impressed with Arkwright's new machine and agreed to form a partnership. On 19th January 1770, for £500, Need and Strutt joined the partners; Arkwright, Thornley and Smalley, were to manage the works, each having £25 a year. Financially secure, the partners commissioned Samuel Stretton to convert the premises into a horse-powered mill.

Arkwright's machine was too large to be operated by hand and so the men had to find another method of working the machine. After experimenting with horses, it was decided to employ the power of the water-wheel. In 1771 the three men set up a large factory next to the River Derwent in Cromford, Derbyshire. Arkwright later that his lawyer that Cromford had been chosen because it offered "a remarkable fine stream of water… in an area very full of inhabitants". Arkwright's machine now became known as the Water-Frame. It not only "spun cotton more rapidly but produced a yarn of finer quality".

Richard Arkwright did not build the first factory in Britain. It is believed that he borrowed the idea from Matthew Boulton, who financed the Soho Manufactory in Birmingham in 1762. However, Arkwright's factory was much larger and was to inspire a generation of capitalist entrepreneurs. According to Adam Hart-Davis: "Arkwright's mill was essentially the first factory of this kind in the world. Never before had people been put to work in such a well-organized way. Never had people been told to come in at a fixed time in the morning, and work all day at a prescribed task. His factories became the model for factories all over the country and all over the world. This was the way to build a factory. And he himself usually followed the same pattern - stone buildings 30 feet wide, 100 feet long, or longer if there was room, and five, six, or seven floors high."

In Cromford there were not enough local people to supply Arkwright with the workers he needed. After building a large number of cottages close to the factory, he imported workers from all over Derbyshire. Within a few months he was employing 600 workers. Arkwright preferred weavers with large families. While the women and children worked in his spinning-factory, the weavers worked at home turning the yarn into cloth.

A local journalist wrote: "Arkwright's machines require so few hands, and those only children, with the assistance of an overlooker. A child can produce as much as would, and did upon an average, employ ten grown up persons. Jennies for spinning with one hundred or two hundred spindles, or more, going all at once, and requiring but one person to manage them. Within the space of ten years, from being a poor man worth £5, Richard Arkwright has purchased an estate of £20,000; while thousands of women, when they can get work, must make a long day to card, spin, and reel 5040 yards of cotton, and for this they have four-pence or five-pence and no more."

Peter Kirby, the author of Child Labour in Britain, 1750-1870 (2003) has argued that it was poverty that forced children into factories: "Poor families living close to a subsistence wage were often forced to draw on more diverse sources of income and had little choice over whether their chidren worked." Michael Anderson has pointed out, that parents "who otherwise showed considerable affection for their children... were yet forced by large families and low wages to send their children to work as soon as possible."

The youngest children in the textile factories were usually employed as scavengers and piecers. Piecers had to lean over the spinning-machine to repair the broken threads. One observer wrote: "The work of the children, in many instances, is reaching over to piece the threads that break; they have so many that they have to mind and they have only so much time to piece these threads because they have to reach while the wheel is coming out."

Scavengers had to pick up the loose cotton from under the machinery. This was extremely dangerous as the children were expected to carry out the task while the machine was still working. David Rowland, worked as a scavenger in Manchester: "The scavenger has to take the brush and sweep under the wheels, and to be under the direction of the spinners and the piecers generally. I frequently had to be under the wheels, and in consequence of the perpetual motion of the machinery, I was liable to accidents constantly. I was very frequently obliged to lie flat, to avoid being run over or caught."

John Fielden, a factory owner, admitted that a great deal of harm was caused by the children spending the whole day on their feet: " At a meeting in Manchester a man claimed that a child in one mill walked twenty-four miles a day. I was surprised by this statement, therefore, when I went home, I went into my own factory, and with a clock before me, I watched a child at work, and having watched her for some time, I then calculated the distance she had to go in a day, and to my surprise, I found it nothing short of twenty miles."

Unguarded machinery was a major problem for children working in factories. One hospital reported that every year it treated nearly a thousand people for wounds and mutilations caused by machines in factories. Michael Ward, a doctor working in Manchester told a parliamentary committee: "When I was a surgeon in the infirmary, accidents were very often admitted to the infirmary, through the children's hands and arms having being caught in the machinery; in many instances the muscles, and the skin is stripped down to the bone, and in some instances a finger or two might be lost. Last summer I visited Lever Street School. The number of children at that time in the school, who were employed in factories, was 106. The number of children who had received injuries from the machinery amounted to very nearly one half. There were forty-seven injured in this way."

William Blizard lectured on surgery and anatomy at the Royal College of Surgeons. He was especially concerned about the impact of this work on young females: "At an early period the bones are not permanently formed, and cannot resist pressure to the same degree as at a mature age, and that is the state of young females; they are liable, particularly from the pressure of the thigh bones upon the lateral parts, to have the pelvis pressed inwards, which creates what is called distortion; and although distortion does not prevent procreation, yet it most likely will produce deadly consequences, either to the mother or the child, when the period."

Elizabeth Bentley, who came from Leeds, was another witness that appeared before the committee. She told of how working in the card-room had seriously damaged her health: "It was so dusty, the dust got up my lungs, and the work was so hard. I got so bad in health, that when I pulled the baskets down, I pulled my bones out of their places." Bentley explained that she was now "considerably deformed". She went on to say: "I was about thirteen years old when it began coming, and it has got worse since."

Samuel Smith, a doctor based in Leeds explained why working in the textile factories was bad for children's health: "Up to twelve or thirteen years of age, the bones are so soft that they will bend in any direction. The foot is formed of an arch of bones of a wedge-like shape. These arches have to sustain the whole weight of the body. I am now frequently in the habit of seeing cases in which this arch has given way. Long continued standing has also a very injurious effect upon the ankles. But the principle effects which I have seen produced in this way have been upon the knees. By long continued standing the knees become so weak that they turn inwards, producing that deformity which is called 'knock-knees' and I have sometimes seen it so striking, that the individual has actually lost twelve inches of his height by it."

John Reed later recalled his life aa a child worker at Cromford Mill: "I continued to work in this factory for ten years, getting gradually advanced in wages, till I had 6s. 3d. per week; which is the highest wages I ever had. I gradually became a cripple, till at the age of nineteen I was unable to stand at the machine, and I was obliged to give it up. The total amount of my earnings was about 130 shillings, and for this sum I have been made a miserable cripple, as you see, and cast off by those who reaped the benefit of my labour, without a single penny."

Richard Arkwright originally produced cotton yarn for stockings, but its possibilities as warp for the loom led, in 1773, to the manufacture of calicos. Jedediah Strutt took responsibility for lobbying Parliament and eventually persuaded its members to reduce excise duties on British-made cotton goods. By February 1774 the partners could, according to Elizabeth Strutt, "sell them … as fast as we could make them."

As J. J. Mason has pointed out: "From the mid-1770s he sought to dominate the trade. In 1775 he successfully applied for a patent for certain instruments and machines for preparing silk, cotton, flax, and wool, for spinning. Covering a range of preparatory and spinning machines, it was an attempt to extend the length and terms of his monopoly to the whole cotton industry".

When businessmen heard about Arkwright's success, they sent spies to find out what was going on in his factories. In exchange for money, some of Arkwright's employees were willing to explain how the factory was organised. Businessmen then used this information to build their own water-powered textile factories. This included spies sent from "many different countries, from Russia, Denmark, Sweden and Prussia, but the most eager of the spies were from Britain's greatest rival, France."

Ralph Mather reported that Arkwright feared that Luddites would destroy his factory: "There is some fear of the mob coming to destroy the works at Cromford, but they are well prepared to receive them should they come here. All the gentlemen in this neighbourhood being determined to defend the works, which have been of such utility to this country. 5,000 or 6,000 men can be at any time assembled in less than an hour by signals agreed upon, who are determined to defend to the very last extremity, the works, by which many hundreds of their wives and children get a decent and comfortable livelihood."

Eric Hobsbawm has argued that in his dealings with his partners he was an "unscrupulous operator". (30) Matthew Boulton described him as a "tyrant". John Smalley suggested to Jedediah Strutt that they should force Arkwright out of the company. Strutt replied. "We cannot stop his mouth or prevent his doing wrong.... but it is not in our power to remove him… for he is in possession and as much right there as we."

Arkwright made further money by selling the rights to use his machines. With the 1769 patent due to expire in the summer of 1783, Arkwright faced losing his controlling hold on the cotton industry. He petitioned parliament that his patents be consolidated and the 1769 patent extended to 1789. However, as Jenny Uglow points out: "Since 1781 Lancashire cotton-spinners had spent a fortune on buildings and machines, employing around thirty thousand people - men, women, and children. They could not afford to become his licensees at prohibitive rates."

In April, 1781, his competitors applied to have the decision annulled. The trial took place in June. Arkwright employed the finest lawyers and an array of witnesses. John Kay and Thomas Highs both gave evidence against Arkwright. He lost the case and a broadsheet in Manchester crowed that "the old Fox is at last caught by his over-grown beard in his own trap".

Arkwright was furious with this decision and he argued that the court's decision would halt the work of other inventors. James Watt, was one of those who gave his support to Arkwright's campaign to extend his patents. Rumours circulated that he was trying to buy up the world's cotton crop. This did not happen but he did set up a company to establish cotton plantations in Africa.

Despite this set-back Arkwright he remained the country's largest cotton spinner; he made huge gains in the 1770s, and even in the early 1780s his profits from the industry seem to have been at 100 per cent per annum. Thomas Carlyle described Arkwright as "a plain, almost gross, bag-cheeked, pot-bellied man, with an air of painful reflection, yet almost copious free digestion".

When Samuel Need died on 14th April, 1781. Arkwright and Jedediah Strutt decided to dissolve their partnership. Strutt was disturbed by Arkwright's plans to build mills in Manchester, Winkworth, Matlock Bath and Bakewell. Strutt believed that Arkwright was expanding too fast and without the support of Need, his long-time partner, he was unwilling to take the risk of further investments. Arkwright's textile factories were very profitable. He now built factories in Lancashire, Staffordshire and Scotland. In these factories he used the new steam-engine that had recently been developed by James Watt and Matthew Boulton.

Arkwright's biographer, J. J. Mason, claimed that: "In 1782 he bought Willersley manor and in 1789 the manor of Cromford. These acquisitions established him more firmly with the local gentry, including the Gells and Nightingales, with whom he was already connected through business.... Society sneered at his extravagance and ridiculed his gauche behaviour... but enjoyed his lavish entertainments in... Rock House, perched high and overlooking the mills and his more stately home, Willersley Castle."

Arkwright was made Sheriff of Derbyshire and was knighted in 1787. King George III told Wilhelmina Murray, that he did not deal very well with the ceremony. "Tthe little great man had no idea of kneeling but crimpt himself up in a very odd posture which I suppose His Majesty took for an easy one so never took the trouble to bid him rise."

Richard Arkwright's employees worked from six in the morning to seven at night. Although some of the factory owners employed children as young as five, Arkwright's policy was to wait until they reached the age of six. Two-thirds of Arkwright's 1,900 workers were children. Like most factory owners, Arkwright was unwilling to employ people over the age of forty.

William Dodd carried out a study into the long-term impact on the physical health of these child workers. This included an interview with John Reed: "Here is a young man, who was evidently intended by nature for a stout-made man, crippled in the prime of life, and all his earthly prospects blasted for ever! Such a cripple I have seldom met with. He cannot stand without a stick in one hand, and leaning on a chair with the other; his legs are twisted in all manner of forms. His body, from the forehead to the knees, forms a curve, similar to the letter C. He dares not go from home, if he could; people stare at him so."

Dodd compared the life of John Reed with that of Richard Arkwright: "I have taken several walks in the neighbourhood of this beautiful and romantic place, and seen the splendid castle, and other buildings belonging to the Arkwrights, and could not avoid contrasting in my mind the present condition of this wealthy family, with the humble condition of its founder in 1768. One might expect that those who have thus risen to such wealth and eminence, would have some compassion upon their poor cripples. If it is only that they need to have them pointed out, and that their attention has hitherto not been drawn to them, I would hope and trust this case of John Reed will yet come under their notice."

Arkwright had difficulty making friends and Josiah Wedgwood claimed that "he shuns all company as much as possible". Archibald Buchanan, who lived with him and found him "so intent on his schemes" they "often sat for weeks together, on opposite sides of the fire without exchanging a syllable".

Richard Arkwright died aged 59 on 3rd August 1792 at his home in Cromford, after a month's illness. On 10th August, over 2,000 by two people attended his funeral. The Gentleman's Magazine claimed that on his death, Arkwright was worth over £500,000 (over £200 million in today's money).

On this day in 1839 Feargus O'Connor argues against a Grand National Holiday (general strike) to get male suffrage. "We believe that the naming of the 12th August was a most ill-judged and suicidal act. To fix the general holiday to begin on the 12th August, would be to involve the whole cause in ruin and confusion - which would place us in circumstances of difficulty, from which we should emerge only through blood and fire, or chains and slavery more dire than any we have yet known. The country is not fit for it; there is no state of adequate preparation; there is no proper organisation amongst the people; they are not able to act in concert with each other. If the suggestion of a month's general holiday be now persisted in and attempted to be acted on, the consequences will be, the splitting of people into sections, and their falling, one section after another, like the divided bundle of sticks, an east prey to the power of their oppressors."

In the early 1830s, William Benbow began advocation his theory of the Grand National Holiday. Benbow argued that a month long General Strike would lead to an uprising and a change in the polical system. Benbow used the term "holiday" (holy day) because it would be a period "most sacred, for it is to be consecrated to promote the happiness and liberty". Benbow argued that during this one month holiday the working class would have the opportunity "to legislate for all mankind; the constitution drawn up... that would place every human being on the same footing. Equal rights, equal enjoyments, equal toil, equal respect, equal share of production."

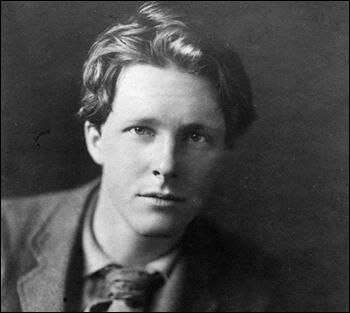

On this day in 1887 Rupert Brooke, the second of the three sons born to William Parker Brooke (1850–1910), a housemaster at Rugby School, was born on 3rd August, 1887. According to his biographer, Adrian Caesar: "Brooke attended a preparatory school, Hillbrow, as a day boy, 1897–1901, and then proceeded to take his place at Rugby. Home and school thus became the same place, and psychologically this situation may have represented the worst of both worlds: he experienced the sexually sequestered and confusing world of the public school, while simultaneously coping with the emotional intensities generated by a possessive mother and a distantly affectionate father."

In 1906 he won a scholarship to King's College. While at Cambridge University Brooke joined the Fabian Society. Other members at Cambridge at the time included: Hugh Dalton, Clifford Allen and Amber Reeves. During this period Brooke met several leaders of the movement including George Bernard Shaw, H. G. Wells, Beatrice Webb and Sidney Webb. Like fellow members he developed an enthusiasm for long walks, camping, nude bathing, and vegetarianism.

Brooke wrote at the time about the Fabians: "they're really sincere, energetic, useful people, and they do a lot of good work." He was especially impressed with Wells who he described as being "fantastic". However, he was more critical of other members. He wrote that he wanted the Fabians to take "a more human view... They confound the means with the end; and think that a compulsory living wage is the end, instead of a good beginning."

Beatrice Webb established the National Committee for the Break-Up of the Poor Law. According to the authors of The First Fabians (1977): "Beatrice directed a campaign of meetings, conferences, summer schools, study circles and propaganda leaflets which within a few months had recruited over sixteen thousand members and had set up branches across the country. Its energies came largely from young people. Rupert Brooke, pedalling around the Cambridgeshire villages with his campaign literature, collected the litany of names for his famous poem on Grantchester, and many aspiring politicians on the left served their apprenticeship in the campaign."

Rupert Brooke began writing poetry and during the next few years had two collections of verse published, Poems (1911) and Georgian Poetry (1913). Adrian Caesar argues: "Despite this parade of achievement, Brooke's private life proceeded from confusion to chaos and crisis. Paradoxically, his emotional and his psychosexual life were ruled by the puritanism which he dissected in his academic writing. To a revulsion from the body he added a deep uncertainty as to the direction of his desires.... James Strachey also remained a close friend during this period, although Brooke refused at least two invitations to share his bed. Further chaste entanglements developed in 1910 and 1911 with Katherine (Ka) Laird Cox (1887–1938) and Elisabeth van Rysselberghe (1889/90–1980) respectively. Brooke's unresolved relationships with Noel and Ka precipitated a nervous breakdown in early 1912, following which he consummated his relationship with Ka. But this led to more misery, and there is some evidence to suggest that Ka bore his stillborn child later that year."

On the outbreak of the First World War Brooke joined the Royal Naval Division and in October 1914 took part in the Antwerp expedition. After this experience he wrote several poems which made him famous including, Peace, Safety and The Soldier. These poems are now considered as representative of the naïve patriotism of Brooke's generation.

In February 1915 Brooke sailed on the Grantully Castle for the Dardanelles. While on board he developed acute blood poisoning and although transferred to a hospital ship died on 23rd April 1915. Rupert Brooke was buried on the Greek island of Skyros.

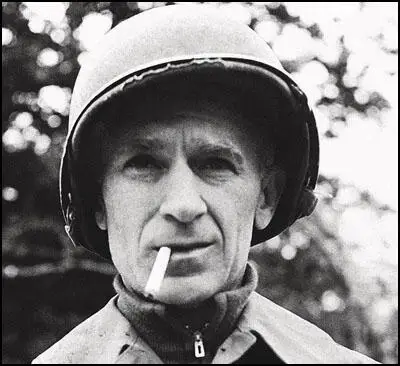

On this day in 1900 journalist Ernie Pyle, the son of a farmer, was born. After studying journalism at Indiana University he found work on a small newspaper in La Porte, Indiana. In 1923 he moved to the Washington Daily News and eventually became the paper's managing editor.

In 1932 he was commissioned to write a travel column for the Scripps-Howard newspaper chain. He did this until the outbreak of the Second World War when he became a war correspondent. He moved to England in 1940 where he reported on the Blitz for the New York World Telegram.

Pyle went with the US Army to North Africa in November 1942. This was followed by the invasions of Sicily and Italy. He also accompanied Allied troops during the Normandy landings and witnessed the liberation of France. By 1944 Pyle had established himself as one of the world's outstanding reporters and Time hailed him as "America's most widely read war correspondent."

John Steinbeck commented: "There is, the war of maps and logistics, of campaigns, of ballistics, armies, divisions, and regiments. Then there is the war of homesick, weary, funny, violent, common men, who wash their socks in their helmets, complain about food, whistle at Arab girls, or any other girls for that matter, and lug themselves through as dirty a business as the world has ever seen and do it with humanity and dignity and courage - and that is Ernie Pyle's war."

Pyle became disillusioned with the war and wrote to his wife: "Of course I am very sick of the war and would like to leave it, and yet I know I can't. I've been part of the misery and tragedy of it for so long that I feel if I left it, it would be like a soldier deserting."

In 1945 Pyle was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for journalism. Later that year he went with US troops to Okinawa. Ernie Pyle was killed by a Japanese sniper while on a routine patrol on 17th April, 1945.

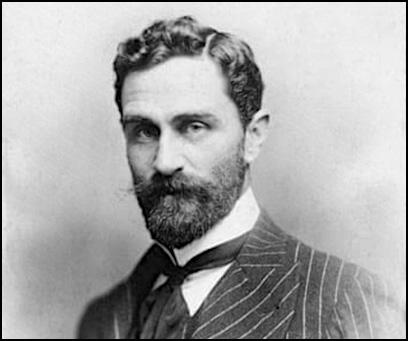

On this day in 1916 Roger Casement was executed at Pentonville Prison. John Ellis, his executioner, called him "the bravest man it ever fell to my unhappy lot to execute".

Roger Casement, the youngest son of Roger Casement (1819–1877) and Anne Jephson (1834–1873), was born on 1st September 1864 at Doyle's Cottage, Sandymount. His father, an Ulster protestant, was a captain in the Dragon Guards.

The children were brought up as Protestants, but his mother had Roger secretly baptized a Roman Catholic in Rhyl, in August 1868. Casement's mother died in childbirth in 1873, and his father in 1877. Roger went to live with his uncle, John Casement, of Magherintemple, near Ballycastle and was educated at a diocesan school in Ballymena.

After he left school in 1880 he went to Liverpool to live with Grace Bannister, his mother's sister, and her family. Casement worked as a clerk in the Elder Dempster Shipping Line Company. However, he disliked office work and when he was nineteen he became purser on the Bonny, a ship bound for the Congo. The following year he returned to Africa where he worked as a surveyor for the Belgians' Congo International Association. Between December 1889 and March 1890 he was companion to Herbert Ward on a lecturing tour in the United States of America.

Casement returned to Ireland and in 1892 he accepted his first British official post as Acting Director-General of Customs. His first consular appointment came in 1895 at Delagoa Bay in Portuguese East Africa (Mozambique). According to his biographer, David George Boyce: "At this point in his career he was stridently pro-British, fulminating against the Boers and Kruger, and was awarded the queen's South Africa medal."

In June 1902 the Foreign Office authorized him to go into the interior and send reports on the misgovernment of the Congo. His report, written in November 1903, contained evidence of cruelty and even mutilation of the Congolese. Casement was deeply upset by the British government's government failure to act on the report's recommendations. However, he was rewarded for his work with a Order of Saint Michael and Saint George (CMG) in 1905.

In July 1906 he accepted the consular post at Santos, Brazil. In 1908 Casement went to Rio de Janeiro as consul-general, and in the following year he was asked by the Foreign Office to investigate atrocities in the Putumayo Basin in Peru. He wrote up his report in 1911 and was rewarded with a knighthood. Casement, who considered himself an Irish Nationalist, recorded in his diary, "I am a queer sort of British consul... one who ought really to be in jail instead of under the Lion & Unicorn."

Casement's interest in politics intensified in 1912 when the Ulster Unionists pledged themselves to resist the imposition of Irish Home Rule, by force if necessary. In 1913 he became a member of the provisional committee set up to act as the governing body of the Irish Volunteer Force (IVF) in opposition to the Ulster Volunteer Force. He helped organize local IVF units, and in May 1914 he declared that "It is quite clear to every Irishman that the only rule John Bull respects is the rifle."

Casement's activities were brought to the attention of Basil Thomson, head of the Special Branch. Thompson later admitted that it was one of his agents, Arthur Maundy Gregory, who told him about Casement's homosexuality. According to Brian Marriner: "Gregory, a man of diverse talents, had various other sidelines. One of them was compiling dossiers on the sexual habits of people in high positions, even Cabinet members, especially those who were homosexual. Gregory himself was probably a latent homosexual, and hung around homosexual haunts in the West End, picking up information.... There is a strong suggestion that he may well have used this sort of material for purposes of blackmail." Thomson later admitted that "Gregory was the first person... to warn that Casement was particularly vulnerable to blackmail and that if we could obtain possession of his diaries they could prove an invaluable weapon with which to fight his influence as a leader of the Irish rebels and an ally of the Germans."

In July 1914 Casement traveled to United States in order to raise support for the IVF. Basil Thomson received information on Casement from Reginald Hall, the director of Naval Intelligence Division of the Royal Navy (NID). Hall was in charge of the code-breaking department Room 40 had discovered the plans hatched in the United States between German diplomats and Irish Republicans.

On the outbreak of the First World War Casement traveled to Berlin. According to the author of Casement: The Flawed Hero (1984): "When the First World War broke out in August he resolved to travel to Germany via Norway in order to urge on the Germans the 'grand idea’ of forming an ‘Irish brigade’ consisting of Irish prisoners of war to fight for Ireland and for Germany". His attempts to persuade Irish prisoners to enlist in his brigade met with a poor response. Private Joseph Mahony, who was in Limburg Prisoner of War Camp, later recalled: "In February 1915 Sir Roger Casement made us a speech asking us to join an Irish Brigade, that this was 'our chance of striking a blow for our country'. He was booed out of the camp... After that further efforts were made to induce us to join by cutting off our rations, the bread ration was cut in half for about two months."

On 4th April 1916, Casement was told that a German submarine would be provided to take him to the west coast of Ireland, where he would rendezvous with a ship carrying arms. The Aud, carrying the weapons, set out from Lübeck on 9th April with instructions to land the arms at Tralee Bay. Unfortunately for Casement, Reginald Hall, the director of Naval Intelligence Division of the Royal Navy (NID), had discovered details of this plan. On 12th April Casement set out in a German U-boat, but because of an error in navigation, Casement failed to arrive at the proposed rendezvous with the ship carrying the weapons. Casement and his two companions, Robert Monteith and David Julian Bailey, embarked in a dinghy and landed on Banna Strand in the small hours of 21st April. Basil Thomson, using information supplied by NID, arranged for the arrest of the three men in Rathoneen.

As Noel Rutherford points out: "Casement's diaries were retrieved from his luggage, and they revealed in graphic detail his secret homosexual life. Thomson had the most incriminating pages photographed and gave them to the American ambassador, who circulated them widely." Later, Victor Grayson claimed that Arthur Maundy Gregory had planting the diaries in Casement's lodgings.

Reginald Hall and Basil Thomson took control of the interrogation of Casement. Christopher Andrew, the author of The Defence of the Realm: The Authorized History of MI5 (2009) has argued: "Casement claimed that during the interrogation at Scotland Yard he asked to be allowed to appeal publicly for the Easter Rising in Ireland to be called off in order to 'stop useless bloodshed'. His interrogators refused, possibly in the hope that the Rising would go ahead and force the government to crush what they saw as a German conspiracy with Irish nationalists." According to Casement, he was told by Hall, "It is better that a cankering sore like this should be cut out.'' This story is supported by Inspector Edward Parker, who was present during the interrogation: "Casement begged to he allowed to communicate with the leaders to try and stop the rising but he was nor allowed. On Easter Sunday at Scotland Yard he implored again to be allowed to communicate or send a message. But they refused, saying, it's a festering sore, it's much better it should come to a head."

The trial of Roger Casement began on 26 June with Frederick Smith leading for the crown. But as David George Boyce points out: "The most controversial aspect of the trial took place outside the courts. Casement's diaries, detailing his homosexual activities, were now in the hands of the British police and intelligence officers shortly after Casement's interrogation at Scotland Yard on 23 April. There are several versions about precisely when and how the diaries were discovered, but they seem to have come to light when Casement's London lodgings were searched following his arrest. By the first weeks of May they were beginning to be used surreptitiously against him. They were shown to British and American press representatives on about 3 May and excerpts were soon widely circulated in London clubs and the House of Commons. This could not have been done without at least an expectation that those higher up would approve, though Smith opposed any use of the diaries to discredit Casement's reputation, as did Sir Edward Grey. The cabinet however made no attempt to stop these activities, the purpose of which was not to ensure that Casement would be hanged - that was inevitable - but that he should be hanged in disgrace, both political and moral."

On 29th June 1916 Casement was found guilty of high treason and sentenced to death. On 30th June he was stripped of his knighthood and on 24th July an appeal was rejected. A campaign for a reprieve was supported by leading political and literary figures, including W. B. Yeats, George Bernard Shaw, John Galsworthy, and Arthur Conan Doyle, but the British public, primarily concerned by the large loss of life on the Western Front, were unmoved by this campaign.

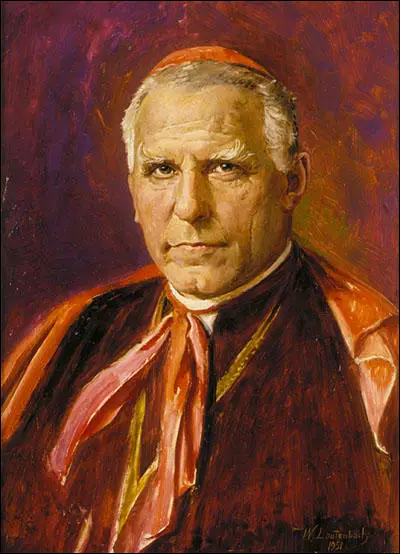

On this day in 1941 August von Galen, Bishop of Münster, preaches a sermon against euthanasia. "If the principle that man is entitled to kill his unproductive fellow man is established and applied, then woe to all of us when we become aged and infirm! Then no man will be safe: some committee or other will be able to put him on the list of `unproductive' persons, who in their judgment have become `unworthy to live'. And there will be no police to protect him, no court to avenge his murder and bring his murderers to justice. Who could then have any confidence in a doctor? He might report a patient as unproductive and then be given instructions to kill him! It does not bear thinking of, the moral depravity, the universal mistrust, which will spread even in the bosom of the family, if this terrible doctrine is tolerated, accepted and put into practice. Woe to mankind! Woe to our German people, if the divine commandment 'Thou shalt not kill', which the Lord proclaimed on Sinai amid thunder and lightning, which God our Creator wrote into man's conscience from the beginning, if this commandment is not merely violated but the violation is tolerated and remains unpunished!"