Clare Sheridan

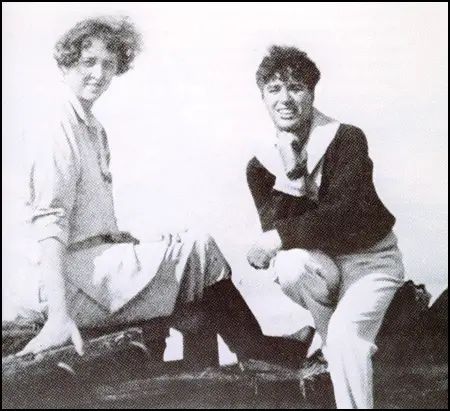

Clare Frewen, the daughter of Moreton Frewen and Clarita Jerome, was born in London on 9th September, 1885. Her mother was the elder sister of Jennie Jerome, who had married Randolph Churchill. She became close friends with their son, Winston Churchill. Clare and her brother, Oswald Frewen, were brought up at Brickwall, a large black-and-white Elizabethan manor in Northiam. They also owned Brede Place near Rye and a house in Innishannon.

Her biographer, Anita Leslie, the author of Clare Sheridan (1976): "As the education of a girl was deemed unimportant, Clare spent most of her time at Innishannon, and revelled in the holidays when the boys re-appeared. Moreton was good with boys. He taught them to climb trees and peer into herons' nests. He was so much more entertaining as a naturalist than a bi-metallist, and he even showed some interest in his daughter when she revealled how well she could ride... When school drew brothers and cousins away, Clare would try to settle down seriously to her books. The governess of the moment would be her only companion indoors, and outdoors, the grooms and poachers. Every now and again Mama appeared and, remembering her own intensive schooling in Paris, would loudly complain that this was no education - but she did nothing to improve matters."

Eventually her parents decided to send her to convent in Paris. She was unhappy and her cousin, Winston Churchill, wrote to her commented: "My dear Clare, do not be low spirited. It is something after all to be fed and clothed and sheltered: more than most people in the world obtain without constant and unwearing toil. Cultivate a philosophical disposition, grow pretty and wise and good."

In 1903 Clare, aged seventeen, fell in love with Wilfred Sheridan, a stockbroker. He set about improving her mind and lent her books, including the works of his ancestor Richard Brinsley Sheridan. Her father, Moreton Frewen, had financial difficulties and wanted her to marry someone with more money. Clare was determined to marry Sheridan. She told Anita Leslie that "in Wilfred's company she felt herself utterly natural, sparkling and gay". Clare later recalled in her autobiography, Naked Truth (1927): "The fact was that not only did I care for Wilfred, but I was paralysed by the general attitude of society towards elder sons. I could not bring myself, however charming they might be (and who shall say that elder sons cannot be charming?) to talk to them without self-consciousness... I could not get rid of the sensation that they knew that I was poor and that I knew they were marriageably desirable. I could not bear that they should think, or that anyone looking on should think, that I made the slightest effort to be unduly amiable.

Clare told Winston Churchill that she wanted to be a writer. One of the reasons was that she wanted to be financially independent of her father. Churchill, who was working as a journalist at the time, advised her that it was better for women to "please and inspire the male sex". Clare received more encouragement from Henry James who lived only four miles away at Rye. She frequently bicycled over to lunch with him in Lamb House. She asked James to introduce her to H.G. Wells but he refused because he did not consider him a "suitable acquaintance for a young girl". Clare also visited Rudyard Kipling at Bateman's House near Burwash but did not find him helpful.

Churchill introduced Clare to Violet Asquith, the daughter of Herbert Henry Asquith, the leader of the Liberal Party. Violet also had literary ambitions and the two young women became close friends. Violet was already being commissioned to write articles for magazines. When the National Review asked her to produce an article on country-house entertaining, she passed the task onto Clare and the contribution earned her £10. It was a well-written article and as a result she was approached by Archibald Constable and Company to write a book.

Clare now began writing a novel. She sent the first draft of the novel to the author and critic, George Moore. He wrote back on 29th June, 1907: "It was with difficulty that I restrained myself this afternoon from writing to you that I had read a third of your book and liked it so much that I had to tell you before reading any further. The phrases that rose up in my mind were: What a dear little book she has written and what a charming girl she must be to have thought so well, so truly and so prettily... There are just a few points to correct and if she were staying in the same house with me it would be a pleasure to revise her book with her, a few touches here and there, deftly done - for it would be a thousand pities to do anything that would change the petal-like flutter of her pages, scented with all the perfume of her young mind. A real young girl's book." Clare had "intended to astound the world with her sophisticated philosophy" and was so distraught by Moore's comments and set fire to the manuscript.

1910 Wilfred Sheridan once again approached Moreton Frewen about marrying Clare. Both sets of parents were against the marriage. According to Anita Leslie, the author of Clare Sheridan (1976): "Wilfred was a great gentleman, he came of the crispest upper crust of the English country aristocracy, he had literary talent in his family, he was often referred to as the best-looking man of his time - scholarly, athletic, a man whom other men admired and respected and who attracted every woman he met. Wilfred's parents did not hide their bitter disappointment. How could the handsome Sheridan heir choose to marry an absolutely penniless girl? It meant he would have to continue earning in the City so that his sons could go to the right schools. Later he would inherit Frampton Court and live quietly in Dorsetshire. He would have books and horses and an estate of 6000 acres to run, but no town house, no travel, no worldly luxuries. Clare and Wilfred had waited so long while elders explained the impossibility of such a match: now they wondered why they had wasted time."

Frewen reluctantly agreed and the proposed marriage was announced in July, 1910. Clare received a letter of support from Henry James: "I give you together what I venture to call a fond benediction, and verily shade my eyes a little before the dazzle of your combined personal lustre". Rudyard Kipling wrote a letter where he suggested that she should now reconsider her attempts to become a writer: "I should chuck poetry and literature if I were you. They don't make for married happiness on the she-side." The couple were married on 15th October 1910. Herbert Henry Asquith, the Prime Minister, and four Cabinet ministers, attended the ceremony. Also there was Winston Churchill and his new bride, Clementine Hozier.

Until they inherited the family home Wilfred and Clare leased a small Tudor house called Mitchem on the estate of his friend William St John Brodrick, 1st Earl of Midleton. His father gave him an allowance of £1,000 that enabled him to employ five servants. Over the next five years Clare gave birth to three children, Margaret, Elizabeth and Richard. Elizabeth unfortunately died of tuberculosis in 1914.

Alan Chedzoy has written: "Wilfred Sheridan, the surviving second son, was now the hope of the Sheridans. Unfortunately, however, his successful city career was ruined when his firm failed... in 1914". On the outbreak of the First World War, Wilfred Sheridan, now aged 35, was desperate to join the British Army. With the help of friends he managed to become a Lieutenant in the Rifle Brigade. He was sent to the Western Front in May, 1915. Clare wrote to a friend: "Black Puss (Wilfred) went to France yesterday - I feel as if if it were the end of the world. I can hardly hold my head up. Didn't know one could live through such hell."

In August 1915, Sheridan spent two weeks on leave at Frampton Court. When it was time to return he insisted they said good-bye at the gate: "I don't want you to come to the station. A station is not a place for good-byes." According to Anita Leslie: "So they parted amidst the green trees. She stood there watching him walk away - so light of step, sunburned and handsome. Once he turned to wave. Then he was gone."

Wilfred Sheridan was killed at the Battle of Loos on 25th September, 1915. A fellow officer wrote to Clare Sheridan about the attack on the German trenches: "We made an attack on Saturday morning at 4.30. I was in the German trench with Mr. Wilfred and another officer. We were going around the trench when a German met us, shot the officer, wounded me and Mr. Wilfred shot him down before going on to the 2nd line leading his Bombers fine. He did not seem to care in the least, he simply went on at the head of them into the Trenches. He was alive and well when I was carried back." Soon afterwards Sheridan was killed by a German sniper.

If you find this article useful, please feel free to share on websites like Reddit. You can follow John Simkin on Twitter, Google+ & Facebook, make a donation to Spartacus Education and subscribe to our monthly newsletter.

Soon afterwards Clare Sheridan found a letter written by her husband: "You will only read this if I am dead, and remember that as you read it I shall be by your side. Remember that all over England are broken hearts and ruined lives, remember that one splendid woman, such as you are, refusing to weep, and hugging her soul with pride at a soldier's death, will consciously or unconsciously stiffen up and bring comfort to these... God keep you and help you and bring my little Margaret up happily. I can leave you nothing, darling, except the memory of years, and you know what our life together has been. Surely if perfection is attained we have attained it."

In 1916, the twenty-year-old, Seymour Edward Frederick Egerton, 6th Earl of Wilton, asked Clare to marry him. Her brother, Oswald Frewen, wrote in his diary: "The fiancé is evidently of generous and lovable disposition. That Puss (Clare) should marry him, an Earl with £90,000 a year aged 20 cannot fail to look bad, and indeed the material benefits accruing thereto are so great for the entire Frewen family indirectly that I have the utmost circumspection in admitting a desire for it even to myself - I don't like the idea of her marrying again when the first union was perfect - but she is not the sort to go coldbloodedly after money & a coronet is certainly nothing to her. He is very much in love with her (his heart is weak and he requires humouring), she is obviously fond of him, old Wilfred expressly told her that if he were killed he hoped she would marry again."

Frewen wrote about the progress of the relationship in February, 1917: "Suddenly, last October, she met Simon who fell in love with her. She accepted a gold wrist watch from him, which shocked me (Lady Annesley describes me as a prude, or a "prig" is it?)... After that I was positively relieved when she said she was engaged to him. He is 20, she is 31. She is, moreover, his first love. He is a Ward in Chancery and his mother disapproves. All her friends were against it, argued it out, said what a dear he was (which he is) & that he is so unlike Wilfred that they don't clash, that Wilfred wanted it. Anyway I finally came round to it. Besides it was her affair & I was loyal to her. They have been engaged now a couple of months, he has been before the judges for permission & got it for April, had a row with his mother, announced it in the papers; now because Puss has tonsillitis which appears to have the same effect as jaundice, she says she isn't going to marry him at all! No reason; just a whim. Thinks she won't be happy - after weighing it all up & saying 'Yes,' now to do a volte-face, shatter his faith in her whole sex, make him miserable, make herself & all of us who were loyal to her the laughing stock of the whole world, & set aside (for what it is worth) a comfortable & assured future for Wilfred's children... I decline to follow her gymnastics any further. She has brought me round to approve of it all; with time & trouble I have reconciled myself to it. I have met him & he is a ripper; and I am just not going to turn again. I would consider any girl who treated any man so, rather a beast if she were young & he were old. I would consider any woman who treated a boy so as a cad."

Clare Sheridan had fallen in love with Alexander Thynne, the son of the John Thynne, 4th Marquis of Bath, and the MP for Bath. Although he was 43 years old he had joined the Wiltshire Regiment on the outbreak of the First World War and given the rank of Lieutenant Colonel. Thynne was wounded twice at the Battle of the Somme in 1916. Clare had met him while he was on leave and described him as "entrancing - alive - able to give a sense of purpose."

Thynne returned to the Western Front to take part in the Battle of Passchendaele in November 1917. Clare heard that "someone high up" was trying to get Thynne out of the trenches but told a mutual friend "don't let him know strings are being pulled". In April 1918 he was slightly wounded in the left arm which gave him a month in London. Clare admitted that she hoped that his wound would go septic, but it healed and he rejoined his regiment and Thynne was killed in action in France on 14th September 1918.

The War Office granted Clare Sheridan a widow's pension of £250 a year. She decided that she would not get married and try to make a living as an artist. She moved to a small studio in St. John's Wood. At first she struggled to get commissions and she was forced to sell Wilfred's collection of English prints and Staffordshire china. Things began to improve when Colonel Dentz became a major sponsor of her work. He gave her £1,000 and also agreed to pay for a portrait by Jacob Epstein. Clare thought this would give her the opportunity to see a great sculptor at work.

Clare recorded the experience in her autobiography, Naked Truth (1927): "Epstein at work was a being transformed. Not only his method was interesting and valuable to watch, but the man himself, his movement, his stooping and bending, his leaping back posed and then rushing forward, his trick of pressing clay from one hand to the other over the top of his head while he scrutinised his work from all angles, was the equivalent of a dance... He wore a butcher-blue tunic and his black curly hair stood on end; he was beautiful when he worked. Then I learnt the thing which has counted supremely for me ever since... He did not model with his fingers, he built up planes slowly by means of small pieces of clay applied with a flat, pliant wooden tool. He told me that he could not understand how other sculptors could work with their fingers which with him merely left shiny fingerprints on the surfaces. This was what I had always suffered from, the shiny smooth result of my finger touch. It had exasperated and perplexed me. It is his method of building up that gives Epstein's surfaces their vibrating and pulsating quality of flesh. Without his ever suspecting it, I acquired from merely watching him, knowledge that revolutionised my work."

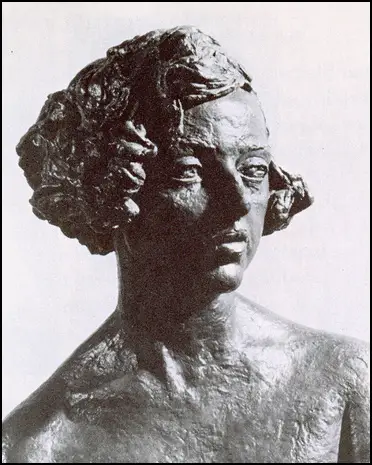

Clare's breakthrough came when she was commissioned to produce a bust of Herbert Henry Asquith for the Oxford Union. It was considered a great success and this resulted in other work. Among her first sitters were H. G. Wells, Arnold Bennett, Winston Churchill, Gladys Cooper and Diana Manners. She later recalled: "Of all the portraits I have ever done Winston's was the hardest, not because his face was difficult, but because for him a physical impossibility to remain still... I watched, I snatched at times and moments, I did and undid and re-did, at times in despair.... Winston would be contrite and promise and say he was sorry and that he knew it was hard on me, and he would sit compassionately for three minutes and then begin to fidget."

Churchill introduced Clare to his great friend, Frederick E. Smith. They soon became lovers. Clarita Frewin wrote to Leonie Leslie about the relationship: "The poor darling does not realise how people enjoy saying unkind things. It is getting to be quite a scandal but Jennie just laughs-she says Clare needs that sort of man to perk her up. I begged her to ask Winston to speak to F.E. (Lord Birkenhead) about it but she says he does not care. He adores Clare, thinks she can do no wrong after all she has suffered and he is devoted to Lord B.-you know how he always stands by his friends. So whatever scandal these two create together is in Winston's view no scandal-they are splendid, and whatever they feel like doing is perfect."

When her mother complained to her about the public scandal of the affair she replied: "I am thirty-five this year and what haven't I been through - this is a happy interlude.... You think in such old-fashioned terms. I don't regard this as a love affair. I'm just enjoying a man's company." Jennie Churchill commented: "You will be careful dear? After all he has a wife and children." Clare replied: "Honestly I know that - I'm doing a head of his daughter Eleanor. She is fascinating."

On 14th August, 1920, Clare Sheridan met Lev Kamenev, the head of the Soviet Trade Delegation that was visiting London at the time. Kamenev agreed to sit for Sheridan: "There is very little modelling in his face, it is a perfect oval, and his nose is straight with the line of his forehead, but turns up slightly at the end, which is a pity. It is difficult to make him look serious, as he smiles all the time Even when his mouth is severe his eyes laugh.... We had wonderful conversations. He told me all kinds of details of the Soviet legislation, their ideals and aims. Their first care, he told me, is for the children, they are the future citizens and require every protection. If parents are too poor to bring up their children, the State will clothe, feed, harbour and educate them until fourteen years old, legitimate and illegitimate alike, and they do not need to be lost to their parents, who can see them whenever they wish. This system, he said, had doubled the percentage of marriages (civil of course), and it had also allayed a good deal of crime - for what crimes are not committed to destroy illegitimate children?"

Clare Sheridan took a holiday with Kamenev on the Isle of Wight. While they were there Kamenev promised her that he would arrange for her to return to Moscow with him. She told her cousin, Shane Leslie, that doing busts of Lenin and Leon Trotsky might bring her world fame. On 5th September 1920, Clare's brother, Oswald Frewen, wrote in his diary: "Puss (Clare) is trying to go to Moscow with Kamenev to sculpt Lenin and Leon Trotsky.... I rather she didn't go but she has got Bolshevism badly - she always reflects the views of the last man she's met - and I think it may cure her to go and see it. She is her own mistress and if I thwarted her by telling Winston, she'd never confide in me again.... I went to the Bolshevik Legation in Bond Street with her and waited while she saw Kamenev. Several typical Bolshies there - degenerate lot."

Sheridan and Kamenev arrived in Moscow on 20th September, 1920. Olga Kameneva was on the station to greet him: "We reached Moscow at 10.30 a.m. and I waited in the train so that Kameneff and his wife could get their tender greetings over without my presence. I watched them through the window: the greeting on one side, however, was not apparent in its tenderness. I waited and they walked up the platform talking with animation. Finally Mrs. Kamenev came into the compartment and shook hands with me. She has small brown eyes and thin lips."

One of the first people she met in Russia was the American journalist, John Reed. She later recalled in her book, Russian Portraits (1921): "We were delayed in starting by John Reed, the American Communist, who came to see him (Kamenev) on some business. He is a well-built good-looking young man, who has given up everything at home to throw his heart and life into work here. I understand the Russian spirit, but what strange force impels an apparently normal young man from the United States?"

On 22nd September, Clare Sheridan went to a political meeting that featured Clara Zetkin, Leon Trotsky and Alexandra Kollontai: "Clara Zetkin, the German Socialist, was speaking, spitting forth venom, as it sounded. The German language is not beautiful, and the ferocious old soul, mopping her plain face with a large handkerchief, was not inspiring. It sounded very hysterical and I only understood an outline of what she was saying. Then Trotsky got up, and translated her speech into Russian. He interested me very much. He is a man with a slim, good figure, splendid fighting countenance, and his whole personality is full of force. I look forward immensely to doing his head. There is something that ought to lend itself to a fine piece of work. The overcrowded house was as still as if it were empty, everyone was attentive and concentrated."

Gregory Zinoviev was the first to agree to sit for Sheridan. "At 3 o'clock I hurried to the Kremlin, as Kamenev had telephoned telling me to expect Zinoviev. I waited until four and then he arrived, busy, tired and impatient, his overcoat slung over his shoulders as though he had not had time to put his arms through the sleeves. He slung off his hat and ran his fingers through his black curly hair, which already was standing on end. He sat restlessly looking up and down, round and out and beyond; then he read his newspaper, every now and again flashing round with an imperative look at me to see how I was getting on. He seemed to me an extraordinary mix-up of conflicting personalities. He has the eyes and brow of the fighting man, and the mouth of a petulant woman."

On 27th September, 1920, she worked on a bust of Felix Dzerzhinsky: "Today Felix Dzerzhinsky came. He is the President of the Extraordinary Commission, or as we should call it in English, the organiser of the Red Terror. He is the man Kameneff has told me so much about. He sat for an hour and a half, quite still and very silent. His eyes certainly looked as if they were bathed in tears of eternal sorrow, but his mouth smiled an indulgent kindness. His face is narrow, with high cheek bones and sunk in. Of all his features his nose seems to have the most character. It is very refined, and the delicate bloodless nostrils suggest the sensitiveness of over-breeding. He is a Pole by origin." Sheridan praised Dzerzhinsky for sitting so still. He replied: "One learns patience and calm in prison." When she asked how long he was in prison. "A quarter of my life, eleven years."

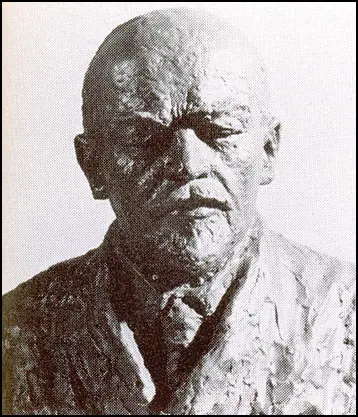

Sheridan did not meet Lenin until 7th October: "Lenin was sitting at his desk. He rose and came across the room to greet me. He has a genial manner and a kindly smile, which puts one instantly at ease. He said that he had heard of me from Kamenev. I apologised for having to bother him. He laughed and explained that the last sculptor had occupied his room for weeks, and that he got so bored with it that he had sworn that it never should happen again. He asked how long I needed, and offered me today and tomorrow from 11 till 4, and three or four evenings, if I could work by electric light. When I told him I worked quickly and should probably not require so much, he said laughingly that he was pleased."

During the session Lenin expressed his dislike of her cousin Winston Churchill: "I asked if Winston was the most hated Englishman. He shrugged his shoulders, and then added something about Churchill being the man with all the force of the capitalists behind him. We argued about that, but he did not want to hear my opinion, his own being quite unshakeable. He talked about Winston being my cousin, and I said rather apologetically that I could not help it, and informed him that I had another cousin who was a Sinn Feiner. He laughed, and said That must be a cheerful party when you three get together. I suppose it would be cheerful, but we have never all three been together! During these four hours he never smoked, and never even drank a cup of tea. I have never worked so long on end before, and at 3.45 I could hold out no longer. I was blind with weariness and hunger, and said good-bye. He promised to sit on the revolving stand tomorrow. If all goes well, I think I ought to be able to finish him. I do hope it is good. I think it looks more like him than any of the busts I have seen yet. He has a curious Slav face, and looks very ill."

Leon Trotsky began sitting for Clare Sheridan on 18th October. She was impressed with Trotsky: "At one time, in his youth, what was he? A Russian exile in a journalist's office. Even then I am told he was witty, but with the wit of bitterness. Now he has come into his own and has unconsciously developed a new individuality. He has the manner and ease of a man born to a great position; he has become a statesman, a ruler, a leader. But if Trotsky were not Trotsky, and the world had never heard of him, one would still appreciate his very brilliant mind. The reason I have found him so much more difficult to do than I expected is on account of his triple personality. He is the cultured, well-read man, he is the vituperative fiery politician, and he can be the mischievous laughing school-boy with a dimple in his cheek. All these three I have seen in turn, and have had to converge them into clay interpretation." According to Robert Service, the author of Trotsky: A Biography (2010), they became lovers during Sheridan's time in Moscow.

Clare Sheridan was devastated by the death of John Reed: "Everyone liked him and his wife, Louise Bryant, the War Correspondent. She is quite young and had only recently joined him. He had been here two years, and Mrs. Reed, unable to obtain a passport, finally came in through Murmansk. Everything possible was done for him, but of course there are no medicaments here: the hospitals are cruelly short of necessities. He should not have died, but he was one of those young, strong men, impatient of illness, and in the early stages he would not take care of himself."

In her book, Russian Portraits (1921), she described the funeral that was also attended by Nickolai Bukharin and Alexandra Kollontai: "It is the first funeral without a religious service that I have ever seen. It did not seem to strike anyone else as peculiar, but it was to me. His coffin stood for some days in the Trades' Union Hall, the walls of which are covered with huge revolutionary cartoons in marvellously bright decorative colouring. We all assembled in that hall. The coffin stood on a dais and was covered with flowers. As a bit of staging it was very effective, but I saw, when they were being carried out, that most of the wreaths were made of tin flowers painted. I suppose they do service for each Revolutionary burial... A large crowd assembled for John Reed's burial and the occasion was one for speeches. Bucharin and Madame Kolontai both spoke. There were speeches in English, French, German and Russian. It took a very long time, and a mixture of rain and snow was falling. Although the poor widow fainted, her friends did not take her away. It was extremely painful to see this white-faced, unconscious woman lying back on the supporting arm of a Foreign Office official, more interested in the speeches than in the human agony."

Clare Sheridan arrived back in England on 23rd November, 1920. She was besieged by reporters. A representative from The Times begged her not to talk to other newspapers and offered her an exclusive deal where she would be well rewarded for her story. Her cousin, Shane Leslie, who was busy negotiating a deal, told her: "Do stick to art and literature and leave politics.... So tread delicately and print nothing that has not passed over my typewriter. If you take my advice I may recover caste with the family!"

Eventually she agreed a deal where The Times to publish her diaries. The New York Times negotiated a contract that gave them the rights to publish them in the United States and the rest of the world. According to Clare's brother, Oswald Frewen: "The telephone rang incessantly with pressmen... The Times gave her £500 for the first installment. We still tried to sell exclusive photo rights, also got her to sign about £400 of most pressing bills." The Times sold the series of extracts from the diaries as: "With Lenin and Trotsky. Diary of an Englishwoman." She later recalled she enjoyed her new-found fame: "All the city clerks read it in the omnibuses and the Tube on the way to work. I boarded both during the rush hours to watch them doing it!"

However, the establishment disliked her apparent sympathy for the Bolshevik government. They were especially hostile to the comments made about communism in her diary on 2nd November, 1920: "My ear has accustomed itself to the language of Communism, I have forgotten the English of my own world. I do not mean that I am a Communist, nor that I think it is a practical theory, perhaps it is not, but it seems to me, nevertheless, that the Russian people get gratis a good many privileges, such as education, lodging, food, railways, theatres, even postage, and a standard wage thrown in. If the absence of prosperity is marked, the absence of poverty is remarkable. The people's sufferings are chiefly caused by lack of food, fuel and clothing. This is not the fault of the Government. The Soviet system does not do it to spite them, or because it enjoys their discomfiture. Only peace with the world can ameliorate their sufferings, and Russia is not at war with the world, the world is at war with Russia. Why am I happy here, shut off from all I belong to? What is there about this country that has always made everyone fall under its spell? I have been wondering. My mind conjures up English life and English conditions, and makes comparisons. Why are these people, who have so much less education, so much more cultured than we are? The galleries of London are empty. In the British Museum one meets an occasional German student. Here the galleries and museums are full of working people. London provides revues and plays of humiliating mediocrity, which the educated classes applaud and enjoy. Here the masses crowd to see Shakespeare. At Covent Garden it is the gallery that cares for music, and the boxes are full of weary fashion, which arrives late and talks all the time. Here the houses are overcrowded with workers and peasants who listen to the most classical operas. Have they only gone as someone might with a new sense of possession to inspect a property they have suddenly inherited? Or have they a true love of the beautiful and a real power of discrimination? These are the questions I ask myself."

Sheridan then went onto argue: "Civilisation has put on so many garments that one has trouble in getting down to reality. One needs to throw off civilisation and to begin anew, and begin better, and all that is required is just courage. What Lenin thinks about nations applies to individuals. Before reconstruction can take place there must be a revolution to obliterate everything in one that existed before. I am appalled by the realisation of my upbringing and the futile view-point instilled into me by an obsolete class tradition. Time is the most valuable material in the world, and there at least we all start equally, but I was taught to scatter mine thoughtlessly, as though it were infinite. Now for the first time I feel morally and mentally free, and yet they say there is no freedom here. If a paper pass or an identification card hampers one's freedom, then it is true. There may be restrictions to the individual, and if I were a Russian subject I might not be allowed to leave the country, but I seem to have been obliged to leave England rather clandestinely. Freedom is an illusion, there really is not any in the world except the freedom one creates intellectually for oneself."

The only new commission Sheridan received after she arrived back in London was by George Lansbury, the Labour Party politician. This brought her to the attention of MI5 who were carrying out an investigation into Lansbury who believed he was receiving funds from the Bolsheviks to run the left-wing newspaper, The Daily Herald. Sheridan later discovered that the MI5 had a "dossier" on her and had been watching Lansbury's visits to her her studio in St John's Wood.

Winston Churchill wrote to her explaining why he had been unwilling to see her: "You did not seek my advice about your going and I was not aware that you needed any on your return. Anyhow it was almost impossible for me to bring myself to meet you fresh from the society of those whom I regard as fiendish criminals. Having nothing to say to you that was pleasant, I thought it better to remain silent until a better time came. But that does not at all mean that I have ceased to regard you with affection or to wish you most earnestly success and happiness in a right way. While you were flushed with your adventure I did not feel you needed me: and frankly I thought I could not trust myself to see you. But no one has felt more sympathy or admiration for your gifts and exertion than I have, and I should be very sorry if you did not feel that I would do my best to help you in any way possible or that you did not count on my friendship and kinship. But note at the same time please that you have those other friends and have to train your words to suit their interests."

Sheridan took the rejection from family and friends badly and decided to move to New York City. Soon after arriving she was asked to visit the home of Bernard Baruch. He later told Anita Leslie: "You can imagine what I expected when Winston asked me to look after a cousin who was lecturing on Russia and had got herself into hot water because of Bolshie propensities. I visualized some grim Communist school marm, and it was not with particular relish that I went to meet this lady whom Winston described as a poor girl. No one could have expected the swan in many coloured cloaks who swept into the Ritz and when I rang her up after she had been to Pittsburgh the voice that answered the phone vibrated like that of some diva at the height of a tragic scene. She needed help! I sent my car around to fetch her... Clare, a large, golden, tearful goddess began to pour out her woes and beg me to subdue her manager and end her contract... I was bowled over. Next day, of course, I saw her manager and settled things. Clare was released. But that was only the beginning of it. She then informed me that she had brought most of her sculpture over in packing cases. These were lying at the docks. It would be nice if I telephoned the Customs men and assured them there were no bombs in those crates labelled Lenin and Trotsky."

Baruch denied that he had an affair with Clare Sheridan: "Every man she met seemed ready to give her a job and run around at her beck and call. I did not have an affair with her-although everyone of course thought I did. You could not take her to a restaurant or to dine in a friend's house without giving that impression. She was wonderful looking, and exciting to have around, but so damn fatiguing. I'm sorry now, maybe, but I was happily married. I did not want upsets.... And she didn't get on with women. She wouldn't try. Something had got into her - energy-sex-drive - she ran around New York like a fire engine out of control, scandalizing high society by saying she couldn't think why women had to depend on men - it was a woman's privilege to bear a child to the lover of her choice and the State should support her financially... I couldn't really take to her - she was too wild."

Bernard Baruch introduced Sheridan to Herbert Swope, the editor of the New York World. Swope invited her to write for his newspaper. Sheridan found him a stimulating companion. She told her friend, Maxine Elliott. "I asked him, when I was able to get a word in edgeways, how he managed to revitalize, he seemed to me to expend so much energy. He said he got it back from me, from everyone, that what he gives out he gets back; it is a sort of circle. He was so vibrant that I found my heart thumping with excitement, as though I had drunk champagne, which I hadn't! He talks a lot, but talks well; is never dull."

Swope agreed a deal where she had the freedom to travel the world interviewing people who interested her. Sheridan's first assignment was to go to Hollywood. This included an interview with Charlie Chaplin. She recorded in her diary: "It has been a wonderful evening - I seem to have been talking heart to heart with one who understands, who is full of deep thought and deep feeling. He is full of ideals and has a passion for all that is beautiful. A real artist... And then in spite of his emotional, enthusiastic temperament, with a soundness of judgement... You can see the sadness of the eyes - which the humour of his smile cannot dispel - this man has suffered... He is not Bolshevik nor Communist nor Revolutionary, as I heard rumoured. He is an individualist with the artist's intolerance of stupidity, insincerity, and narrow prejudice." Chaplin advised her against becoming too political: "Don't get lost on the path of propaganda. Live your life as an artist."

Sheridan began a romantic relationship with Charlie Chaplin. She later confessed that: "It was not exactly a love affair but a meeting of kindred spirits - we were like two fireflies intoxicated with the same magical feeling for beauty - dancing together by the waves, recognising each other's souls." They were constantly being followed by journalists. One newspaper published the headline: "Charlie Chaplin going to marry British Aristocrat". In one interview concerning age he answered truthfully: "Mrs. Sheridan is four years older than I am." When the article was published it claimed that Chaplin said: "She is old enough to be my mother." Eventually they decided to bring an end to the relationship.

Sheridan had taken her two children, Margaret and Richard (Dick), to Hollywood. Margaret explained in her autobiography, Morning Glory (1957): "For the first time, looking at her when she came up to say goodnight to us, I realised how beautiful she was. But the pitch of American life was too much for her. She thrived on high pressure, but it told on her nerves.... She swished through life... Her air of helplessness before any difficulty was as deceptive as the childlike affability she assumed when about to say or do some scandalous thing, eyeing the world lambently in all innocence, spotless before the fury of her enemies... She was lovely but embarrassing; as a mother impossible, as a person enchanting. With her superb disregard for consequences, taking risks and making others share them, she was always alive, never dim."

Clare Sheridan's brother, Oswald Frewen, described her on her arrival at Paddington Station: "She looked tall, handsome and matronly... She greeted me with affection and calmness - it is strange that she should have to go to America to learn calm... Dick and Margaret, clutching dolls and tin steamers, agreeably filled in the picture. Before we had left Paddington I made two new discoveries about Puss: she has grown up and she radiates personality, not as a glow-worm radiates light, but as a furnace radiates heat: a dynamic personality. I feel she is very akin to Winston, that her orb has risen; it may wax and wane, it may even be eclipsed, but it won't set... We returned to the studio and she walked in. Immediately she began to criticise her own early work and damned practically everything except Winston and the Bolshie busts to destruction."

In 1922 Sheridan went to interview Benito Mussolini who had recently appointed as Prime Minister of Italy. His first words to Sheridan was "I know all about you and your connections with the Russians". She responded with: "What do you think of their efforts? I want to write about your attitudes to the working classes." Mussolini reponded: "The working classes are studid, dirty, lazy and only need the cinema. They must be taken care of and learn to obey."

Mussolini then began talking about himself: "I come of peasant stock. My father was a blacksmith - he gave me strength. And my mother, she was sweet and sensitive - a school teacher - a lover of poetry - she feared my tempestuous nature, but she loved me - and I loved her." Sheridan later recalled that this was the only note of gentleness she perceived in him.

Sheridan asked him why his wife was not living in Rome? He replied: "Never! Women - children - belongings - luxury - they clutter up - one cannot work with all that round one's neck. Art and literature are different - they lighten, they inspire." At the door he kissed her hand as before, unsmiling. "Never let your enthusiasm rob you of your appetite - keep your heart a desert."

The following day Sheridan returned to see Mussolini. Her biographer, Anita Leslie, the author of Clare Sheridan (1976): has pointed out: "The Fascist guards and detectives were accustomed to her now. They bowed her to the landing. That evening she swarmed in, swathed as always in floating veils, and set to work on the first sketches. Mussolini sat staring through her - or so she thought. Her pencil drew the basic lines - it was difficult not to create a caricature for his face was in itself an exaggeration of feature and expression. How contented she felt at getting him to pose at last. What did she care about his politics? It was the power of that mask she must catch. Luckily she did not have to sketch his feet-they were large feet encased in spats and when he stamped about on them she could hardly keep her face straight. Then suddenly she looked up and saw him advancing. According to Sheridan his "nostrils flaring-head down like an angry bull." Mussolini commented: "You will not leave till dawn, and then you will be broken in".

Anita Leslie continued: "He must seduce her. Sketch-book and clay flew to the ceiling, slaps, punches, wrestling, gasping cries of amazement (on both sides) filled the room. Clare couldn't believe it true. Neither could Mussolini - she was taller than he, but he was stronger.... He blocked the way to the main door, but grabbing her handbag she made for the side exit. He got there before her and there was, according to her own account, a veritable hand-to-hand struggle for the key. Clare managed to snatch it and open the door. It took a long time, she said. But eventually she managed to wedge it open with her foot. Mussolini threw his whole heavy weight against the door to close it and caught her elbow in the process. Her screams of pain halted him. Purple in the face he stood back for a moment and she was able to wrench herself from his grasp."

In March, 1923, Herbert Swope, the editor of the New York World, put her on a $100 a week contract and sent her to Berlin. Her brother, Oswald Frewen, was now working for The Daily Telegraph and he travelled with her to Germany. One of her first reports was on Adolf Hitler: "In Munich Mr. Hitler had raised an army of Fascists and threatened violence to the German Republic. That he fizzled out into a mere nothing could not have been foreseen. At the moment he seemed all-important."

Sheridan and Frewen also interviewed Maxim Gorky in Freiberg. Frewen wrote in his diary: "Gorky told us he left Russia because the Soviet government were not for Russia but for Internationalism, and he was for Russia. Why did he live in Germany? Because he could get visas for nowhere else." Gorky told them that he thought the peasants were better off after the Russian Revolution. "When asked about the attendant miseries, he replied that a rainy day is good for the potatoes."

After General Miguel Primo de Rivera obtained power in Spain Sheridan and Frewen travelled to Madrid. Frewen wrote in his diary: "We retired to the Hotel to write and pack. We are the only correspondents to whom he has granted a special interview, and we are off with our loot." They then caught the evening train to Paris on which King Alfonso XIII also happened to be travelling: "Puss (Clare) stopped dead in the middle of the swaying compartment to drop a most unbolshevistic curtsey."

Sheridan and Frewen next went to Moscow where they had a meeting with Maxim Litvinov, the Deputy Commissar for Foreign Affairs. He was interested in talking about Winston Churchill: "Two first cousins of that abominable Churchill meet at my table. What hostages! I ought to arrest you both - that man cost Russia thousands of lives by prolonging our Civil War." Litvinov was unwilling to arrange any interviews with members of the government. Sheridan wrote: "What was I to write about the New Russia; how circumvent the dreadful anti-climax? I felt as a woman might who, having dreamed of reunion with a lover after years of faithful separation, met him and he turned his back upon her."

On her return to London Sheridan wrote a series of hostile articles in The Daily Express about the Soviet Union. According to Anita Leslie, the author of Clare Sheridan (1976): "As Clare's latest articles in the Daily Express criticized Russia, her previous infatuation with the Communist regime was forgiven, and Mrs. Sheridan found herself lionized by London Society. She greatly enjoyed it while continuing to lament bitterly the disillusion of her great love, the Soviet Union."

Christian Rakovsky, the Soviet Ambassador, called her in to complain about her articles. He offered to arrange for her to visit the Ukraine to see how much progress was being made. Her brother, Oswald Frewen, agreed to go with her. It was decided to travel to Russia across Holland, Germany, Czechoslovakia and Poland on a motorbike and side-car. Frewen claimed that the only way she got a visa was because "Rakovsky's fallen for her. They all do. And in the end she'll be shot. The couple left on 6th July 1924."

Sheridan produced Rakovsy's letter to the guards on the Poland-Russia border. The officer commented: "We have been waiting for you for two days. All Russia is yours." While in Odessa they met William Norman Ewer and Rose Cohen. Ewer, was the diplomatic correspondent of The Daily Herald. Frewen fell in love with Cohen. He wrote in his diary: "She has probably been thinking that I was rather in love with her and that unless she kept a trifle aloof I might get a trifle unmanageable. She is old enough anyway for all her childish appearance, to have that amount of worldly wisdom . Frank, friendly, gentle but aesthetic, unconventional and a communist, I wonder just how I shall react to her in London. Bare legs and a Tartar dress are her setting. How will she appear in Mount Street?"

On her return to London Sheridan decided to write novels such as Opal Fire and Green Amber, two travel books, Across Europe with Satanella (1925) and A Turkish Kaleidoscope (1926) and an autobiography, Naked Truth (1927). However, she prefered creating sculptures. "While writing I watch the clock to see if it's lunch time, whereas with my hands in the clay I don't know or care if the day has gone."

In 1931 Algernon Thomas Sheridan died. Clare Sheridan's son, Richard Sheridan, became heir to Frampton Court and over 6,000 acres. Clare wrote to her mother: "Dick will other something like £3,500 a year when he's of age, and tax will reduce that by a further £1,000. Therefore he could not live at Frampton which requires at least £6,000... I had a great thrill seeing a quantity of silver, mostly Georgian, and all heirlooms going to the bank in Dorchester."

Sheridan went to live at Brede Place near Rye. Her daughter, Margaret Sheridan married a French Army officer, Comte Guy de Reneville. General Jean de Lattre de Tassigny, described him as "the most likeable lunatic in the French Army". The couple moved to French Equatorial Africa and Margaret, adopting the name Mary Motley, became a novelist.

In 1937 her son Richard died of appendicitis, aged twenty-one, at Biskra in the Sahara. She later recalled that the death changed her art: "How strange that through losing one child I discovered myself as a modeller, through losing another I found myself a carver. It seemed to me I hadn't been a sculptor until now, for modelling is not sculpting. To tackle wood is a great sensation. Wood lives, comes to life under one's hand, one wrestles with it, humours it, coaxes it, argues with it. The grain gives fight."

Clare Sheridan was a pacifist and strongly disapproved of the Second World War. However, she spent a lot of time during this period with Winston Churchill, the Prime Minister, when he was staying at Chartwell. She wrote in her diary that on one of these occasions, when it was time for her to leave, Churchill gave her a hug and told her, Remember... our love is eternal!" She added: "For a flash he was as near and dear as a brother, but all too quickly he soars away and is lost in a mist of preoccupation."

Sometimes she joined Churchill at the underground shelter at 10 Downing Street. She recorded on one visit: "Winston was in bed reading a newspaper. When he lowered it I saw a Hogarthian figure with cigar and spectacles. The light was bad, each side of his bed encumbered by tables laden with papers. When I uncovered my block, into which I had already marked a suggestion of him, he seemed to approve that it was slightly bigger than life."

Churchill agreed to pose for Sheridan. On another occasion they discussed Benito Mussolini. Clare Sheridan, who completely disliked the man, said: "I got the notion you rather admired him." Churchill replied: "I did - a very able man. He should never have come in against us. In fact, this whole war could have been prevented if it had not been for so many bungling statesmen." Churchill liked the bust: "I think you have produced a very fine piece of work. I should certainly like to have a replica of the head in bronze."

Clare Sheridan had lunch with Churchill in June 1948. "Winston, in his dreadful boiler suit was looking pale. He rants, of course, about the inefficient ignorant crowd now in power, who are what he calls throwing the British Empire away. He is almost heartbroken. All his life he has been such a great Imperialist. He is so brilliant, but unless one can make notes in shorthand one cannot recapture all he says. He quotes so aptly, which I envy, having myself no memory. He quoted Hamlet several times which illustrates his spirit of despondency... He has finished three volumes of his new book The Second World War, and only the possibility of being called back into politics prevents him going on with it."

Churchill's health continued to deteriorate and in 1955 he reluctantly retired from politics. Clare Sheridan remembers visiting his home in London after he left politics. She found him very depressed. He told her that he felt a failure. She replied: "How can you!" You beat the Nazis." Churchill remained sunk in gloom: "Yes.... we had to fight those Nazis - it would have been too terrible had we failed. But in the end you have your art. The Empire I believed in has gone."

Clare Sheridan died at Parnham House, on the outskirts of Beaminster, on 31st May 1970.

Primary Sources

(1) Clare Sheridan, Naked Truth (1927)

The fact was that not only did I care for Wilfred, but I was paralysed by the general attitude of society towards elder sons. I could not bring myself, however charming they might be (and who shall say that elder sons cannot be charming?) to talk to them without self-consciousness... I could not get rid of the sensation that they knew that I was poor and that I knew they were marriageably desirable. I could not bear that they should think, or that anyone looking on should think, that I made the slightest effort to be unduly amiable.

(2) George Moore, letter to Clare Sheridan (29th June, 1907)

It was with difficulty that I restrained myself this afternoon from writing to you that I had read a third of your book and liked it so much that I had to tell you before reading any further. The phrases that rose up in my mind were: "What a dear little book she has written and what a charming girl she must be to have thought so well, so truly and so prettily... There are just a few points to correct and if she were staying in the same house with me it would be a pleasure to revise her book with her, a few touches here and there, deftly done - for it would be a thousand pities to do anything that would change the petal-like flutter of her pages, scented with all the perfume of her young mind. A real young girl's book."

(3) Anita Leslie, Clare Sheridan (1976)

Wilfred was a great gentleman, he came of the crispest upper crust of the English country aristocracy, he had literary talent in his family, he was often referred to as the best-looking man of his time - scholarly, athletic, a man whom other men admired and respected and who attracted every woman he met. Wilfred's parents did not hide their bitter disappointment. How could the handsome Sheridan heir choose to marry an absolutely penniless girl? It meant he would have to continue earning in the City so that his sons could go to the right schools. Later he would inherit Frampton Court and live quietly in Dorsetshire. He would have books and horses and an estate of 6000 acres to run, but no town house, no travel, no worldly luxuries. Clare and Wilfred had waited so long while elders explained the impossibility of such a match: now they wondered why they had wasted time.

(4) Wilfred Sheridan, letter to Clare Sheridan (August 1915)

You will only read this if I am dead, and remember that as you read it I shall be by your side . Remember that all over England are broken hearts and ruined lives, remember that one splendid woman, such as you are, refusing to weep, and hugging her soul with pride at a soldier's death, will consciously or unconsciously stiffen up and bring comfort to these... God keep you and help you and bring my little Margaret up happily. I can leave you nothing, darling, except the memory of years, and you know what our life together has been. Surely if perfection is attained we have attained it.

(5) Henry James, letter to Clare Sheridan (October, 1915)

The thought of coming into your presence and into Mrs. Sheridan's with such empty and helpless hands is in itself paralysing; and yet even so I say that, the sense of my whole soul is full, even to its being racked and torn, of Wilfred's belovedest image and the splendour and devotion in which he is all radiantly enwrapped and enshrined, makes me ask myself if I don't really bring you something of a sort, in thus giving you the assurance of how absolutely I adored him! Yet who can give you anything that approaches your incomparable sense that he was yours, and you his, to the last possessed and possessing radiance of him.

(6) Oswald Frewen, diary entry (16th December, 1916)

The fiance is evidently of generous and lovable disposition. That Puss (Clare) should marry him, an Earl with £90,000 a year aged 20 cannot fail to look bad, and indeed the material benefits accruing thereto are so great for the entire Frewen family indirectly that I have the utmost circumspection in admitting a desire for it even to myself - I don't like the idea of her marrying again when the first union was perfect - but she is not the sort to go coldbloodedly after money & a coronet is certainly nothing to her. He is very much in love with her (his heart is weak and he requires humouring), she is obviously fond of him, old Wilfred expressly told her that if he were killed he hoped she would marry again.

(7) Clare Sheridan, Naked Truth (1927)

Those days are unforgettable. Epstein at work was a being transformed. Not only his method was interesting and valuable to watch, but the man himself, his movement, his stooping and bending, his leaping back posed and then rushing forward, his trick of pressing clay from one hand to the other over the top of his head while he scrutinised his work from all angles, was the equivalent of a dance...

He wore a butcher-blue tunic and his black curly hair stood on end; he was beautiful when he worked. Then I learnt the thing which has counted supremely for me ever since... He did not model with his fingers, he built up planes slowly by means of small pieces of clay applied with a flat, pliant wooden tool. He told me that he could not understand how other sculptors could work with their fingers which with him merely left shiny fingerprints on the surfaces. This was what I had always suffered from, the shiny smooth result of my finger touch. It had exasperated and perplexed me. It is his method of building up that gives Epstein's surfaces their vibrating and pulsating quality of flesh. Without his ever suspecting it, I acquired from merely watching him, knowledge that revolutionised my work.

(8) Clare Sheridan, Naked Truth (1927)

Birkenhead, who had been painted by every artist in London was self-appointed critic. Sometimes McEvoy joined the party and would try to paint Winston while Winston painted me, and I modelled him. No one would keep still for the other, and it was small wonder that no one got very far. Of all the portraits I have ever done Winston's was the hardest, not because his face was difficult, but because it was for him a physical impossibility to remain still. He said that Sunday was his only day in the week to paint, and so I waited, I watched, I snatched at times and moments, I did and undid and re-did, at times in despair. Freddy would come in, beseech him to "give her a chance" and "it's for me, Winston," and Winston would be contrite and promise and say he was sorry and that he knew it was hard on me, and he would sit compassionately for three minutes and then begin to fidget. Not only would he not keep still for me, but more usually he expected me to keep still for him! Once a secretary arrived from the War Office with a locked despatch box. He stood there, but Winston went on painting, neither seeing nor hearing. For some time the secretary watched us both; I looked at him wondering what he thought, and saw that he was smiling.

Now and then Winston, remembering me, and that I was trying to portray him, would stop still and face me with all the intensity with which he had been painting. These were my momentary chances which he called sittings!

When the light faded he would leave his canvas and turn excitedly to the window where he had a sketch of the cedar tree outside waiting for the sunset background. During one of these passionate moments of trying to catch the dying colour he said to me, without turning round, "Sometimes - I could almost give up everything for it."

(9) Hilda Johnson, Clare Sheridan's cook, letter to Anita Leslie (1975)

My mother always said Lord Alex was the love of Clare's life, after Captain Sheridan. She used to talk to Clare for hours and saved her from many indiscretions, but Lord B-she could not turn her away from. It was partly him being Mr. Winston's good friend. They had awful rows, him and Clare, and once he told her (when she was going out with American officers) that someone at his luncheon table had said she was promiscuous. Well you can imagine what Clare said to that. "Your guests said what at your table?" Well then, he would get round her again and Birkenhead and she would discuss what a child of theirs would be like - the old story about her beautiful body and his brains. But my mother said there were enough reproductions of him. Later on when Lord Birkenhead was holding forth as President of the Divorce Court, my mother was so incensed she wrote him a letter asking him his right to moralise. This was long after his affair with Clare, of course.

(10) Oswald Frewen, diary entry (17th August, 1920)

Winston was.... interesting about the Bolsheviks, France having just recognised Wrangel, a South Russian anti-Bolshevik leader. He said nobody hated Bolshevism more than he, but Bolsheviks were like crocodiles. He would like to shoot everyone he saw, but there were two ways of dealing with them - you could hunt them or let them alone, and it was sometimes too expensive to go on hunting them for ever. This from our fire-eating Minister for War was interesting.

(11) Clare Sheridan, Russian Portraits (1921)

17th August, 1920: There is very little modelling in his face, it is a perfect oval, and his nose is straight with the line of his forehead, but turns up slightly at the end, which is a pity. It is difficult to make him look serious, as he smiles all the time Even when his mouth is severe his eyes laugh....

We had wonderful conversations. He told me all kinds of details of the Soviet legislation, their ideals and aims. Their first care, he told me, is for the children, they are the future citizens and require every protection. If parents are too poor to bring up their children, the State will clothe, feed, harbour and educate them until fourteen years old, legitimate and illegitimate alike, and they do not need to be lost to their parents, who can see them whenever they wish. This system, he said, had doubled the percentage of marriages (civil of course), and it had also allayed a good deal of crime - for what crimes are not committed to destroy illegitimate children?

(12) Clare Sheridan, Russian Portraits (1921)

12th September, 1920: Kamenev had a cigarette in my cabin this evening, and we discussed Philosophy, Religion, and Revolution. It surprised me very much that he does not believe in God. He says that the idea of God is a domination and that he resents it, as he resents all other dominations. He talked nevertheless with great admiration of the teachings of Christ, Who demanded poverty and equality among men, and Who said that the rich man had no more chance of the Kingdom of Heaven than a camel of passing through a needle's eye.

(13) Clare Sheridan, Russian Portraits (1921)

20th September, 1920: Yesterday evening after we had started, Kamenev left us to go and talk to Zinoviev who was on the Petrograd train, travelling also to Moscow. Zinoviev is President of the Petrograd Soviet (and also of the Third International). I did not see Kamenev again that evening, but at 2 a.m. he knocked at my door and awakened me with many apologies to tell me news he thought I should like to hear. Zinoviev had just told him that the telegram announcing his arrival with me came in the middle of a Soviet Conference. It caused a good deal of amusement, but Lenin said that whatever one felt about it there was nothing to do but to give me some sittings as I had come so far for the purpose. "So Lenin has consented and I thought it was worth while to wake you up to tell you that." Kamenev was in great spirits; Zinoviev had evidently told him things he was glad to hear, especially, I gathered, that no blame or censure was going to be put upon him for having failed in his mission to England.

We reached Moscow at 10.30 a.m. and I waited in the train so that Kamenev and his wife could get their tender greetings over without my presence. I watched them through the window: the greeting on one side, however, was not apparent in its tenderness. I waited and they walked up the platform talking with animation. Finally Mrs. Kamenev came into the compartment and shook hands with me. Mrs. Philip Snowden in her book has described her as "an amiable little lady".

She has small brown eyes and thin lips. She looked at the remains of our breakfast on the saloon table and said

querulously, "We don't live chic like that in Moscow." Goodness, I thought, not even like that! There was more

discussion in Russian between the two, and my expressionless face watched them. I have become reconciled to not being unable to understand.As we left the train she said to me: "Leo Kamenev has quite forgotten about Russia, the people here will say he is a bourgeois." Leo Kameneff spat upon the platform in the most plebeian way, I suppose to disprove this. It was extremely unlike him.

We piled into a beautiful open Rolls-Royce car and were driven at full speed with a great deal of hooting through streets that were shuttered as after an air raid. Mrs. Kamenev said to me: "It is dirty, our Moscow, isn't it?" Well, yes, one could not very well say that it was not.

We came to the Kremlin. It is high up and dominates Moscow and consists of the main palace, some other palaces, convents, monasteries, and churches encircled by a wall and towers. The sun was shining when we arrived and all the gold domes were glittering in the light. Everywhere one looked there were domes and towers.

We drove up to a side entrance under an archway, and then made our way, a solemn procession, carrying luggage up endless stone stairs and along stone corridors to the Kamenev apartments. A little peasant maid with a yellow handkerchief tied over her head ran out to greet us, and kissed Kamenev on the mouth. Then ensued the awkward moment of being shown to no room. After eleven days travelling one felt a longing for peace, and to be able to unpack, instead of which the Russian discussion was resumed, and I sat stupidly still with nothing to say.

(14) Clare Sheridan, Russian Portraits (1921)

22nd September, 1920: Mrs. Kamenev went to her work as usual at 10 a.m. At breakfast half an hour later Leo Borisvitch, as he is called, promised not to do any work or keep any engagement until he had taken me to my new headquarters in a guest-house. We were delayed in starting by John Reed, the American Communist, who came to see him on some business. He is a well-built good-looking young man, who has given up everything at home to throw his heart and life into work here. I understand the Russian spirit, but what strange force impels an apparently normal young man from the United States.

(15) Clare Sheridan, Russian Portraits (1921)

22nd September, 1920: Clara Zetkin, the German Socialist, was speaking, spitting forth venom, as it sounded. The German language is not beautiful, and the ferocious old soul, mopping her plain face with a large handkerchief, was not inspiring. It sounded very hysterical and I only understood an outline of what she was saying. Then Trotsky got up, and translated her speech into Russian. He interested me very much. He is a man with a slim, good figure, splendid fighting countenance, and his whole personality is full of force. I look forward immensely to doing his head. There is something that ought to lend itself to a fine piece of work. The overcrowded house was as still as if it were empty, everyone was attentive and concentrated.

After Trotsky Mme. Kolontai spoke. She has short dark hair. Perhaps she spoke well, but of that I could not judge. Tired of standing and of not understanding I left the theatre at the moment when a great many repetitions of Churchill's and Lloyd George's names were rocking the house with laughter.

(16) Clare Sheridan, Russian Portraits (1921)

26th September, 1920: At 3 o'clock I hurried to the Kremlin, as Kamenev had telephoned telling me to expect Zinoviev. I waited until four and then he arrived, busy, tired and impatient, his overcoat slung over his shoulders as though he had not had time to put his arms through the sleeves. He slung off his hat and ran his fingers through his black curly hair, which already was standing on end. He sat restlessly looking up and down, round and out and beyond; then he read his newspaper, every now and again flashing round with an imperative look at me to see how I was getting on. He seemed to me an extraordinary mix-up of conflicting personalities. He has the eyes and brow of the fighting man, and the mouth of a petulant woman.

(17) Clare Sheridan, Russian Portraits (1921)

27th September, 1920: Things begin to move more rapidly now, and my patience is being rewarded. Today Felix Dzerzhinsky came. He is the President of the Extraordinary Commission, or as we should call it in English, the organiser of the Red Terror. He is the man Kameneff has told me so much about. He sat for an hour and a half, quite still and very silent. His eyes certainly looked as if they were bathed in tears of eternal sorrow, but his mouth smiled an indulgent kindness. His face is narrow, with high cheek bones and sunk in. Of all his features his nose seems to

have the most character. It is very refined, and the delicate bloodless nostrils suggest the sensitiveness of over-breeding. He is a Pole by origin.As I worked and watched him during that hour and a half he made a curious impression on me. Finally, overwhelmed by his quietude, I exclaimed : "You are an angel to sit so still." Our medium was German, which made fluent conversation between us impossible, but he answered: "One learns patience and calm in prison."

I asked how long he was in prison. "A quarter of my life, eleven years," he answered. It was the Revolution that liberated him. Obviously it is not the abstract desire for power or for a political career that has made Revolutionaries of such men, but a fanatical conviction of the wrongs to be righted for the cause of humanity and national progress. For this cause men of sensitive intellect have endured years of imprisonment.

(18) Clare Sheridan, Russian Portraits (1921)

3rd October, 1920: I have been five days out of work. It seems much longer. I am told that there are people in Moscow who have been waiting six months to accomplish the business they came for. Lenin seems to me further away than he did in London. There is nothing to do here unless one has work. Never could one have imagined a world in which there is absolutely no social life and no shops. There are no newspapers (for me) and no letters, either to be received or written. There are no meals to look forward to, and comfort cannot be sought in a hot bath. When one has seen all the galleries, and they are open only half a day, and some of them not every day, and when one has walked over cobblestones until one's feet ache, there is nothing more to be done. One must have work to do. Perhaps I should be calmer if I had already accomplished Lenin, but my anxiety is lest I should have to wait weary weeks. Return to London without his head I cannot.

(19) Clare Sheridan, Russian Portraits (1921)

7th October, 1920: Michael Borodin accompanied me to the Kremlin. On the way he said to me: "Just remember that you are going to do the best bit of work today that you have ever done." I was anxious, rather, about the conditions of the room and the light.

We went in by a special door, guarded by a sentry, and on the third floor we went through several doors and passages, each guarded. As I was expected, the sentries had received orders to let me pass. Finally, we went through two rooms full of women secretaries. The last room contained about five women at five tables, and they all looked at me curiously, but they knew my errand. Here Michael handed me over to a little hunchback, Lenin's private secretary, and left me. She pointed to a white baize door, and I went through. It did not latch, but merely swung behind me.

Lenin was sitting at his desk. He rose and came across the room to greet me. He has a genial manner and a kindly smile, which puts one instantly at ease. He said that he had heard of me from Kamenev. I apologised for having to bother him. He laughed and explained that the last sculptor had occupied his room for weeks, and that he got so bored with it that he had sworn that it never should happen again. He asked how long I needed, and offered me today and tomorrow from 11 till 4, and three or four evenings, if I could work by electric light. When I told him I worked quickly and should probably not require so much, he said laughingly that he was pleased.

My stand and things were then brought into the room by three soldiers, and I established myself on the left. It was hard work, for he was lower than the clay and did not revolve, nor did he keep still. But the room was so peaceful, and he on the whole took so little notice of me, that I worked with great calm till 3.45, without stopping for rest or food.

During that time he had but one interview, but the telephone was of great assistance to me. When the low buzz, accompanied by the lighting up of a small electric bulb, signified a telephone call, his face lost the dullness of repose and became animated and interesting. He gesticulated to the telephone as though it understood.

I remarked on the comparative stillness of his room, and he laughed. "Wait till there is a political discussion!" he said.

Secretaries came in at intervals with letters. He opened them, signed the empty envelope, and gave it back, a form of receipt I suppose. Some papers were brought him to sign, and he signed, but whilst looking at something else instead of at his signature.I asked him why he had women secretaries. He said because all the men were at the war, and that caused us to talk of Poland. I understood that peace with Poland had been signed yesterday, but he says not, that forces are at work trying to upset the negotiations, and that the position is very grave.

"Besides," he said, "when we have settled Poland, we have got Wrangel." I asked if Wrangel was negligible, and he said that Wrangel counted quite a bit, which is a different attitude from that adopted by the other Russians I have met, who have laughed scornfully at the idea of Wrangel.

We talked about H. G. Wells, and he said that the only book of his he had read was Joan and Peter, but that he had not read it to the end. He liked the description at the beginning of the English intellectual bourgeois life. He admitted that he should have read, and regretted not having read, some of the earlier fantastic novels about wars in the air and the world set free. I am told that Lenin manages to get through a good deal of reading. On his desk was a volume by Chiozza Money. He asked me if I had had any trouble in getting through to his room, and I explained that Borodin had accompanied me. I then had the face to suggest that Borodin, being an extremely intelligent man who can speak good English, would make a good Ambassador to England when there is peace. Lenin looked at me with the most amused expression, his eyes seemed to see right through me, and then said: "That would please Monsieur Churchill wouldn't it?" I asked if Winston was the most hated Englishman. He shrugged his shoulders, and then added

something about Churchill being the man with all the force of the capitalists behind him. We argued about that, but he did not want to hear my opinion, his own being quite unshakeable. He talked about Winston being my cousin, and I said rather apologetically that I could not help it, and informed him that I had another cousin who was a Sinn Feiner. He laughed, and said "That must be a cheerful party when you three get together." I suppose it would be cheerful, but we have never all three been together!During these four hours he never smoked, and never even drank a cup of tea. I have never worked so long on end before, and at 3.45 I could hold out no longer. I was blind with weariness and hunger, and said good-bye. He promised to sit on the revolving stand tomorrow. If all goes well, I think I ought to be able to finish him. I do hope it is good. I think it looks more like him than any of the busts I have seen yet. He has a curious Slav face, and looks very ill.

When I asked for news of England, he offered me the three latest Daily Heralds he had, dated September 21, 22 and 23. I brought them back and we all fell upon them, Russians and American alike. As for me, I have spent a blissful evening reading about the Irish Rebellion and the Miners' dispute, as if it were yesterday's news, and the Irene Munro and Bamberger cases. Goodness, one feels as though one had looked through a window and seen home on the horizon.

(20) Clare Sheridan, Russian Portraits (1921)

8th October, 1920: Started work again in Lenin's room. I went by myself this time, and got past all the sentries with the pass that I had been given. I took my kodak with me, although I had not the necessary kodak permission. I put a coat over my arm, which hid it.

I don't know how I got through my day. I had to work on him from afar. My real chance came when a Comrade arrived for an interview, and then for the first time Lenin sat and talked facing the window, so that I was able to see his full face and in a good light.

The Comrade remained a long time, and conversation was very animated. Never did I see anyone make so many faces. Lenin laughed and frowned, and looked thoughtful, sad, and humorous all in turn. His eyebrows twitched, sometimes they went right up, and then again they puckered together maliciously.

I watched these expressions, waited, hesitated, and then made my selection with a frantic rush - it was his screwed-up look. Wonderful! No one else has such a look, it is his alone. Every now and then he seemed to be conscious of my presence, and gave a piercing, enigmatical look in my direction. If I had been a spy pretending not to understand Russian, I wonder whether I should have learnt interesting things! The Comrade, when he left the room, stopped and looked at my work, and said the only word that I understand, which is carascho, it means "good", and then said something about my having the character of the man, so I was glad.

After that Lenin consented to sit on the revolving stand. It seemed to amuse him very much. He said he never had sat so high. When I kneeled down to look at the glances from below, his face adopted an expression of surprise and embarrassment.

I laughed and asked: "Are you unaccustomed to this attitude in woman?" At that moment a secretary came in, and I cannot think why they were both so amused. They talked rapid Russian together, and laughed a good deal.

When the secretary had gone, he became serious and asked me a few questions. Did I work hard in London? I said it was my life. How many hours a day? An average of seven. He made no comment on this, but it seemed to satisfy him. Until then, I had the feeling that, although he was charming to me, he looked upon me a little resentfully as a bourgeoise. I believe that he always asks people, if he does not know them, about their work and their origin, and makes up his mind about them accordingly. I showed him photographs of some of my busts and also of "Victory". He was emphatic in not liking the "Victory", his point being that I had made it too beautiful.

I protested that the sacrifice involved made Victory beautiful, but he would not agree. "That is the fault of bourgeois art, it always beautifies."

I looked at him fiercely. "Do you accuse me of bourgeois art?"

"I accuse you!" he answered, then held up the photograph of Dick's bust. "I do not accuse you of embellishing this, but I pray you not to embellish me."

He then looked at Winston. "Is that Churchill himself? You have embellished him." He seemed to have this on the brain.

I said: "Give me a message to take back to Winston."