Christopher Feake

Christopher Feake, the eldest of five children of Edward Feake, of Godstone was probably born in 1612. He entered Emmanuel College, University of Cambridge, in 1628, aged sixteen, graduated BA in 1632. This was followed with a MA in 1635. By 1637 he had married Jane Man, who over the next few years gave birth to eight children. (1)

In the year of his marriage he became vicar of Elsham, North Lincolnshire. In January 1646 he moved to All Saints Church in Hertford. By this time he was a Fifth Monarchists and he dispensed with psalm-singing and the Lord's prayer, and preached against monarchy and aristocracy, asserting that there was in them "an enmity against Christ" which he intended to destroy. (2)

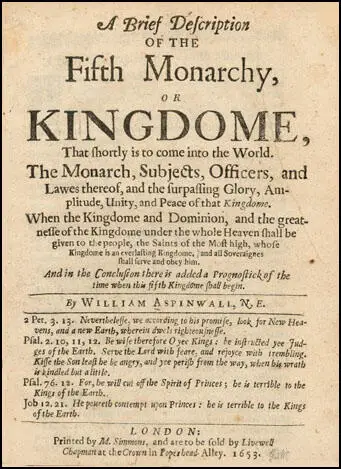

The Fifth Monarchists believed that the overthrow of Charles I was a prophetic moment, signalling the coming of the new millennium and the reign of Christ and the saints on earth. This was as a result of their close reading of the prophecies of the Book of Daniel, in which the fall of the four earthly empires (Assyrian, Persian, Greek and Roman) would be followed by the rule of "King Jesus" and his saints. (3)

Christopher Feake and Oliver Cromwell

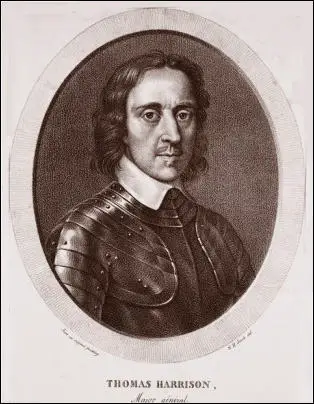

In 1647, Christopher Feake became vicar of Christ Church Greyfriars, and shortly thereafter lecturer at both St Ann Blackfriars and All Hallows-the-Great. In 1652, on the recommendation of Major-General Thomas Harrison, he preached before the House of Commons. In 1654 he was removed from his posts on account of being "obnoxious to the government". It was from these pulpits that his descent into notoriety may be said to have commenced in earnest. (4)

Feake had became one of the movement's recognized leaders and one of the most hostile and outspoken critics of Oliver Cromwell and his government, which he had with some reservation initially supported. In 1653 Feake denounced Cromwell as "the man of sin". (5) Cromwell found these comments unacceptable and both Feake and Vavasour Powell, another Fifth Monarchist was arrested and imprisoned but was released after a few weeks. (6)

In January 1654 Feake was arrested again and imprisoned in Windsor Castle, for "the preservation of the peace of this nation". Feake, however, continued to lead the Fifth Monarchy movement from prison, notably through his pen, and he quickly published fourteen letters he had sent to followers urging the faithful, among other things, to be ready to raise an army "for the King of saints". (7)

John Rogers, another Fifth Monarchists took up Feake's case. He sent a letter to Cromwell opposing the rule of government by one person. Having been weaned from monarchy, England must be governed by parliaments elected annually or biennially, but with royalists excluded from the franchise. Rogers also renounced the use of weapons to oppose the protectorate and called for the release of Christopher Feake and other Fifth Monarchists in prison. (8)

Leader of the Fifth Monarchists

In 1654 Feake published two of his most influential works, The New Non-Conformist and The Oppressed Close Prisoner, where he reluctantly conceded that Cromwell was the de facto but not the de jure ruler, an admission that was insufficient to obtain his release. He also preached from his cell window until he could scarcely speak for hoarseness, and teaching his young son to sing "the Protector is a fool". (9) However, he did say "tyranny itself is not so ugly a monster by many degrees… as is anarchy". (10)

In September 1655 Feake was removed to the Isle of Wight, where he remained in prison first with Major General Thomas Harrison and later with Sir Henry Vane (the younger), until his release from Carisbrooke Castle on 31st December 1656. Feake returned without permission to London, where he resumed his public opposition to Cromwell. At a meeting the following year he denounced the government as being "as Babylonish as ever". (11)

In April 1657 Thomas Venner planned a rising that was backed by a manifesto, a flag that depicted a red lion and the motto "Who shall rouse him up?" The rebels intended to rendezvous at Mile End Green and then march into East Anglia, where they expected many recruits to join them. Venner and about 25 other men were arrested in London before "their plans for a theocracy and government according to biblical lore had been put to much of a test." (12) Feake refused to join the rebellion but when he condemned the arrest of its leaders and was briefly imprisoned in the Tower. (13)

Restoration

On the Restoration the two leading Fifth Monarchists, Thomas Harrison and John Carew were obvious targets for the Royalists. Harrison and Carew refused to flee the country and was therefore like other Regicides arrested and brought to the Tower of London. At his trial in October 1660 Harrison asserted that he had acted in the name of the parliament of England and by their authority. "Maybe I might be a little mistaken, but I did it all according to the best of my understanding, desiring to make the revealed will of God in his holy scriptures as a guide to me". (14)

Harrison claimed he had been acting on the authority of the House of Commons: Denzil Holles rejected this argument. "You do very well know that this that you did, this horrid, detestable act which you committed, could never be perfected by you till you had broken the Parliament. That House of Commons, which you say gave you authority, you know what yourself made of it when you pulled out the speaker; therefore do not make the Parliament to be the author of your black crimes." (15)

Harrison was found guilty of treason and was sentenced to be hung, drawn and quartered. On 13th October 1660 he was taken on a sledge to Charing Cross, the place of his execution. On the way to his execution, Harrison said: "I go to suffer upon the account of the most glorious cause that ever was in the world." (16) Harrison said on the scaffold: "Gentleman, by reason of some scoffing, that I do hear, I judge that some do think I am afraid to die... I tell you no, but it is by reason of much blood I have lost in the wars, and many wounds I have received in my body which caused this shaking and weakness in my nerves." (17)

John Carew was also arrested and at his trial denied being "moved by the devil" and professed obedience to God's "holy and righteous laws" and the authority of an act of parliament. Found guilty, he was executed at Charing Cross on 15 October, although his family was granted his body for private burial rather than having to suffer the ignominy of its public display. Carew went to the scaffold confident that his prosecutors would be destroyed by the wrath of God, and by the "resurrection of this cause". He said that his own blood would "warm the blood that had been shed, and cause notable execution to come down upon the head of their enemy" (18)

After the execution of Harrison and Carew, Feake kept a low profile. He is recorded as a teacher at Dorking in 1662. The following year he was arrested in Dorking and taken back to London for questioning, but was released on a good-behaviour bond. In 1672 he was licensed as an Independent. The date of Christopher Feake's death is unknown. (19)

Primary Sources

(1) Bryan W. Ball, Christopher Feake: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (January, 2000)

Christopher Feake's clerical career began uneventfully as vicar of Elsham, Lincolnshire, about 1637. In January 1646 he obtained the sequestered vicarage of All Saints, Hertford, where his leanings to unorthodoxy soon became apparent. He dispensed with psalm-singing and the Lord's prayer, and preached against monarchy and aristocracy, asserting that there was in them "an enmity against Christ" which he intended to destroy. In 1647, upon the sequestration of the incumbent, William Jenkyn, Feake became vicar of Christ Church, Newgate, and shortly thereafter lecturer at both St Ann Blackfriars and All Hallows-the-Great, livings which by 1654 he had forfeited on account of being "obnoxious to the government".. It was from these pulpits that his descent into notoriety may be said to have commenced in earnest.

Early in the 1650s Feake's oratorical skills and use of the pulpit to incite as well as to instruct were recognized as useful tools in attempts to destabilize the government. In 1650 he preached before the lord mayor of London in support of the fifth monarchy prophesied by Daniel, and in 1652, on the recommendation of Major-General Harrison, before the House of Commons. By the end of 1651 Feake, now an Independent, was one of a group in London beginning to organize the Fifth Monarchists, a movement which felt itself called to establish the latter-day fifth kingdom of Daniel's prophetic visions, using force if necessary. Feake's own interest in the prophecies of Daniel and Revelation is said to have been provoked by the anti-prayer-book riots in Edinburgh in 1637. Feake soon became one of the movement's recognized leaders and one of the most hostile and outspoken critics of Cromwell and his government, which he had with some reservation initially supported.