The Blackout in the Second World War

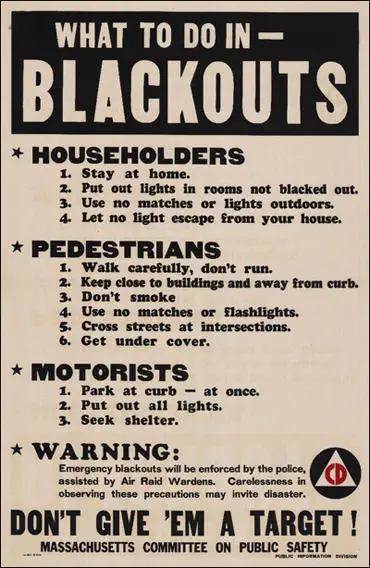

To make it difficult for the German bombers, the British government imposed a total blackout during the war. Every person had to make sure that they did not provide any lights that would give clues to the German pilots that they were passing over built-up areas. All householders had to use thick black curtains or blackout paint to stop any light showing through their windows. Shopkeepers not only had to black out their windows, but also had to provide a means for customers to leave and enter their premises without letting any light escape. (1)

Most people had to spend five minutes or more every evening blacking out their homes. "If they left a chink visible from the streets, an impertinent air raid warden or policeman would be knocking at their door, or ringing the bell with its new touch of luminous paint. There was an understandable tendency to neglect skylights and back windows. Having struggled with drawing pins and thick paper, or with heavy black curtains, citizens might contemplate going out after supper - and then reject the idea and settle down for a long read and an early night." (2)

At first lighting restrictions were enforced with improbable severity. On 22nd November 1940, a Naval Reserve officer was fined at Yarmouth for striking matches in a telephone kiosk so that a woman could see the dial. Ernest Walls from Eastbourne was fined for striking a match to light his pipe. In another case a man was arrested because his cigar glowed alternately brighter and dimmer, so that he might be signalling to a German aircraft. A young mother was prosecuted for running into a room, where the baby was having a fit, and turning on the light without first securing the blackout curtains." (3)

No light whatsoever was allowed on the streets. All street lights were turned off. Even the red glow from a cigarette was banned, and a man who struck a match to look for his false teeth was fined ten shillings. Later, permission was given for small torches to be used on the streets, providing the beam was masked by tissue paper and pointed downwards. There were several cases where the courts appeared to act unfairly. George Lovell put up his blackout curtain and then went outside to make sure they were effective. They were not and while he was checking he was arrested and later fined by the courts for breaking blackout regulations. One historian has argued that the blackout "transformed conditions of life more thoroughly than any other single feature of the war". (4)

Jean Lucey Pratt, who lived in Slough, got into trouble with the authorities for blackout offences: "Not only left light on in bedroom in February but again about four weeks later and the whole performance of policemen climbing in after dark when I was out, to turn out light, was repeated. Excused myself from attending court for first summons and was fined 30 shillings. On the second occasion was charged with breaking blackout regulations and wasting fuel.... I attended court as bidden last Monday morning, quaking. I was expecting to have to pay out £5; at least £3 for the second blackout offence and £2 for the fuel charge. I pleaded guilty, accepted the policeman's evidence and explained in a small voice that I worked from 8.30 to 6 every day, was alone in the cottage, had no domestic help, had to get myself up and off in the morning by 8 o'clock, had not been well and in the early morning rush it was easy to forget the light. The bench went into a huddle and then I heard the chairman saying, '£1 for each charge'. £2 in all! I paid promptly." (5)

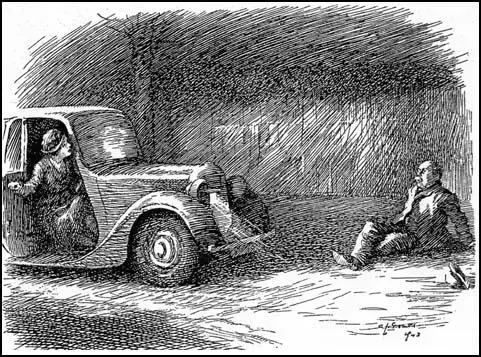

The blackout caused serious problems for people travelling by motor car. In September 1939 it was announced that the only car sidelights were allowed. The results were alarming. Car accidents increased and the number of people killed on the roads almost doubled. The king's surgeon, Wilfred Trotter, wrote an article for the British Medical Journal where he pointed out that by "frightening the nation into blackout regulations, the Luftwaffe was able to kill 600 British citizens a month without ever taking to the air, at a cost to itself of exactly nothing." (6)

Harold Nicolson wrote about the problem in his diary: "Motor up ... to London. There are few signs of any undue activity beyond a few khaki figures at Staplehurst and some schoolboys filling sandbags at Maidstone. When we get near London we see a row of balloons hanging like black spots in the air. Go down to the House of Commons at 5.30. They have already darkened the building and lowered the lights... I dine at the Beefsteak (Club).... When I leave the Club, I am startled to find a perfectly black city. Nothing could be more dramatic or give one more of a shock than to leave the familiar Beefsteak and to find outside not the glitter of all the sky-signs, but a pall of black velvet." (7)

The Daily Telegraph reported in October, 1939: "Road deaths in Great Britain have more than doubled since the introduction of the black-out, it was revealed by the Ministry of Transport accident figures for September, issued yesterday. Last month 1,130 people were killed, compared with 617 in August and 554 in September last year. Of these, 633 were pedestrians." The Transport Minister Euan Wallace, "made an earnest appeal to all motor-drivers to recognise the need for a general and substantial reduction of speed in blackout conditions." (8)

The government was eventually forced to change the regulations. Dipped headlights were permitted as long as the driver had headlamp covers with three horizontal slits. To help drivers see where they were going in the dark, white lines were painted along the middle of the road. Curb edges and car bumpers were also painted white. To reduce accidents a 20 mph speed limit was imposed on night drivers. Ironically, the first man to be convicted for this offence was driving a hearse. Hand torches, were now allowed, if they were dimmed with a double thickness of white tissue paper and were switched off during elerts. (9)

The cities, without neon signs were utterly transformed after dark. According to Joyce Storey: "The cinema was a bible black bob. No bright neon emblazoned the names of the stars and the feature film revolving round and round in a star-studded endless silver square. These had been extinguished at the onset of the war. There wasn't even the all important grey liveried attendant with the gold braid epaulets on his shoulder shouting on the steps the number of seats available in the balcony. A very full, pleated blackout curtain now draped the great doors at the entrance to the foyer. Once inside their voluptuous folds, you came face to face with a high plywood partition forming a corridor along which the patrons shuffled. A sharp turn to the right at the end of this makeshift entrance led to the dimly lit paybox. So low was the light in that gloom, that it was advisable to have the right amount of money for the ticket; sometimes the keenest eye found it difficult to discern whether the right change had been given." (10)

The railways were also blacked out. Blinds on passenger trains were kept drawn and light-bulbs were painted blue. During air-raids all lights were extinguished on the trains. There were no lights on railway stations and although platform edges were painted white, a large number of accidents took place. It was very difficult to see when a train had arrived at a station and, even when this was established, to discover the name of the station. It became fairly common for passengers to get off at the wrong station - and sometimes for them to leave the carriage where there was no station at all. According to an official source these measures were causing "anxieties of women and young girls in the darkened streets at night or in blacked-out trains." (11)

In November 1939 the government agreed that churches, markets and street stalls could be partially illuminated. It was also agreed that restaurants and cinemas could use illuminated signs but these had to be put out when the air raid sirens sounded. The government also gave permission for local authorities to introduce glimmer lighting. This was specially altered street lamps that gave limited light in city centres and at road junctions. Winston Churchill issued a memorandum explaining that these changes were necessary in order to raise the "people's spirits". (12)

Primary Sources

(1) British government circular Lighting Restrictions (July, 1939)

All windows, skylights, glazed doors or other openings which would show a light, will have to be screened in wartime with dark blinds or brown paper on the glass so that no light is visible from outside. You should now obtain any materials you may need for this purpose. Instructions will be issued about the dimming of lights on vehicles. No street lighting is allowed.

(2) Henry (Chips) Channon, diary entry (14th September, 1939)

We are on the very verge of war, as Poland was this morning invaded by Germany, who will now carve up the country with the help of the Russians. At home there were more 'goodbyes', and Honor (Channon) has gone to Kelvedon. There is a blackout, complete and utter darkness, and all day the servants had been frantically hanging black curtains.

(3) Kenneth Sinclair Loutit, Very Little Luggage (2009)

London was a very heartening place during the Blitz. A week later, for a split second, I thought I was being blown up, because I did leave the ground. I had beens driving along King's Cross Road in the black-out during a raid. Bombs were dropping, but you were no safer stationary than moving. I had no lights on because they bothered people; there was no moon; it was cloudy. The Luftwaffe had no special need to aim. London was a large enough target tto be hard to miss. There was a lot of noise, some of it from rail mounted AA. Then, suddenly, my car became airborne, it seemed to rise and came down with a fantastic crash. A little later, as I came to my senses, I heard a voice saying "Are you all right?" I found myself still in the driver’s seat with my hands on the steering wheel. I could not see a thing; the window was open. Looking through it I saw earth, looking up I could just identify a man looking down from three of four feet higher. I've no idea what I said, but he and his mate came down to my level. "Sure you'r OK Guv?" "You gave us a scare, never seen a car do the long jump before." said the other. They were Gas, Light and Coke Company men. The night before there had been some bad Gas ruptures; they had opened up a very big pit to get at the mains for re-routing. Bowling along without headlamps, alone in the middle of an empty totally dark road, I had not seen any difference in the quality of the black in front of my car, so I had driven smartly over the edge into the pit. The car's roof was just below street level, but there was no ramp up; there was plenty of room but no way out. Like many other Blitz problems this was instantly solved. Pure muscle power did it; the car was lifted up by some twenty willing hands and received by twenty others. Placed on its wheels beyond the pit, I started the engine. It worked; I arrived at Finsbury where we found that the steering had been badly damaged and that I had a few bruises.

(4) Harold Nicolson, diary entry (1st September, 1939)

Motor up ... to London. There are few signs of any undue activity beyond a few khaki figures at Staplehurst and some schoolboys filling sandbags at Maidstone. When we get near London we see a row of balloons hanging like black spots in the air. Go down to the House of Commons at 5.30. They have already darkened the building and lowered the lights... I dine at the Beefsteak (Club).... When I leave the Club, I am startled to find a perfectly black city. Nothing could be more dramatic or give one more of a shock than to leave the familiar Beefsteak and to find outside not the glitter of all the sky-signs, but a pall of black velvet.

(5) Joyce Storey, Joyce's War (1992)

The cinema was a bible black bob. No bright neon emblazoned the names of the stars and the feature film revolving round and round in a star-studded endless silver square. These had been extinguished at the onset of the war. There wasn't even the all important grey liveried attendant with the gold braid epaulets on his shoulder shouting on the steps the number of seats available in the balcony. A very full, pleated blackout curtain now draped the great doors at the entrance to the foyer. Once inside their voluptuous folds, you came face to face with a high plywood partition forming a corridor along which the patrons shuffled. A sharp turn to the right at the end of this makeshift entrance led to the dimly lit paybox. So low was the light in that gloom, that it was advisable to have the right amount of money for the ticket; sometimes the keenest eye found it difficult to discern whether the right change had been given.

(6) Lord Chief Justice Caldecote criticised the Lighting Restrictions Order in a judgement made on 19th November, 1942.

This order... ran to some thirty-three articles and innumerable sub-paragraphs which everybody concerned with lighting in its various forms is required to understand ... I find it impossible to believe that the regulations could not have been in a simpler and more intelligible form.

(7) The East Grinstead Observer (30th September, 1944)

Susan Home of 33 West Street, East Grinstead, was charged with a breach of blackout regulations. The light was showing through the scullery window. The window had not been blacked out. The light, added Inspector Fry, had been burning for 14 hours or so and consequently the defendant was also summoned for wasting fuel. Susan Home was fined 10s. for each offence.

(8) The East Grinstead Observer (23rd October, 1944)

Delay in replacing windows broken through enemy action led to the appearance of Laura Miller of 10 High Street, East Grinstead at the local Petty Sessions on Monday for causing an unscreened light to be displayed at her premises at 8.30 on 26th September and for wasting fuel. P.C. Jeal stated that he saw a bright light shining from a window at number 10, High Street. As he did not receive any reply, he forced an entry through the bathroom window and extinguished an electric lamp.

Laura Miller explained "I went out in a hurry about 7 p.m. and must have forgotten to turn out the light." She added that some of the windows which were broken recently by enemy action had been blacked-out with felt, and if it had not been for that, the light would not have been see. Mr. E. Blount said taking all the circumstances into consideration, only small penalties would be imposed. The defendant was fined 10s. on each summons.

(9) Angus Calder, The People's War: Britain 1939-45 (1969)

The first impact of war was felt, not like a hammer blow at the head, to be warded off, but as a mass of itches, to be scratched and pondered. Most of the discomforts and frustrations of the period were very minor foretastes of the years of regulations and austerity which followed. The blackout, however, was an exception. Its impact was comprehensive and immediate. One of the most impassive official historians of the British effort observes, without exaggeration, that it 'transformed conditions of life more thoroughly than any other single feature of the war'.

In the first place, most people had to spend five minutes or more every evening blacking out their homes. If they left a chink visible from the streets, an impertinent air raid warden or policeman would be knocking at their door, or ringing the bell with its new touch of luminous paint. There was an understandable tendency to neglect skylights and back windows. Having struggled with drawing pins and thick paper, or with heavy black curtains, citizens might contemplate going out after supper - and then reject the idea and settle down for a long read and an early night.

For to make one's way from back street or suburb to the city centre was a prospect fraught with depression and even danger. In September 1939 the total of people killed in road accidents increased by nearly one hundred per cent. This excludes others who walked into canals, fell down steps, plunged through glass roofs and toppled from railway platforms. A Gallup Poll published in January 1940 showed that by that stage about one person in five could claim to have sustained some injury as a result of the blackout - not serious, in most cases, but it was painful enough to walk into trees in the dark, fall over a kerb, crash into a pile of sandbags, or merely cannonade off a fat pedestrian.