Road Transport

The blackout caused serious problems for people travelling by motor car. In 1939 only car sidelights were allowed. The results were alarming. Car accidents increased and the number of people killed on the roads almost doubled. The government was forced to change the regulations. Dipped headlights were permitted as long as the driver had headlamp covers with three horizontal slits. To help drivers see where they were going in the dark, white lines were painted along the middle of the road. Curb edges and car bumpers were also painted white. To reduce accidents a 20 mph speed limit was imposed on night drivers.

Three weeks after the outbreak of the Second World War the government introduced petrol rationing. Critics claimed that the basic civilian monthly ration was so low that it could be used up in a day. However, this measure was successful at reducing the number of cars on the road.

The railways were also blacked out. Blinds on passenger trains were kept drawn and light-bulbs were painted blue. During air-raids all lights were extinguished on the trains. There were no lights on railway stations and although platform edges were painted white, a large number of accidents took place. It was very difficult to see when a train had arrived at a station and, even when this was established, to discover the name of the station. It became fairly common for passengers to get off at the wrong station - and sometimes for them to leave the carriage where there was no station at all.

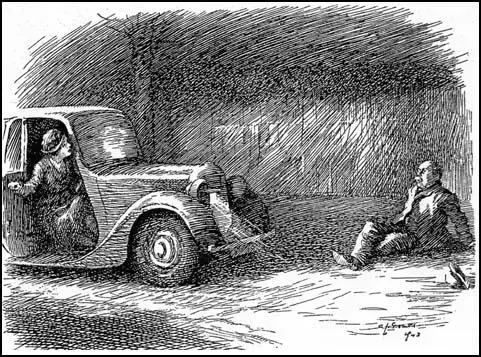

Cartoon published in March, 1943

Primary Sources

(1) Vera Brittain, England's Hour (1941)

Trains became slow, crowded and devoid of restaurants. Before nightfall the blinds are drawn down, and the railway carriage, if lighted at all, is illuminated by a blue pinpoint of light not strong enough to enable me to distinguish the features in the pale ovals which are my neighbours' faces.

(2) Evelyn Waugh, Put Out More Flags (1942)

The first-class carriage was quite full, four a side, and the racks were piled high with baggage. Black funnel-shaped shields cast the light on to the passengers' laps; their faces in the surrounding darkness were indistinguishable; a naval paymaster-commander slept peacefully in one corner, two civilians strained their eyes over the evening papers; the other four were soldiers.

(3) Anthony Powell, The Valley of Bones (1964)

The train, long, grimy, closely packed, subject to many delays . . . pushed south towards London. Within the carriages cold fug stiflingly prevailed, dimmed bulbs, just luminous .... At a halt in the Midlands, night without (outside) still dark as the pit, the Lancashire Fusilier next to me, who had remarked earlier he was going on leave in this neighbourhood, at once guessed the name of the totally blacked-out station, collected his kit and quitted the compartment hurriedly. His departure was welcome, even the more crowded seat now enjoying improved leg-room.

"Is there a breakfast car on this train?" asked the Green Howard. "No", said the Durham Light Infantryman. "Where do you think you are - the Ritz?"

One of the Signals said there was hope of a cup of tea, possibly food in some form, at the next stop, a junction where the train was alleged to remain for ten minutes or more.

(4) Angus Calder, The People's War (1969)

The first impact of war was felt, not like a hammer blow at the head, to be warded off, but as a mass of itches, to be scratched and pondered. Most of the discomforts and frustrations of the period were very minor foretastes of the

years of regulations and austerity which followed. The blackout, however, was an exception. Its impact was comprehensive and immediate. One of the most impassive official historians of the British effort observes, without exaggeration, that it 'transformed conditions of life more thoroughly than any other single feature of the war'.

In the first place, most people had to spend five minutes or more every evening blacking out their homes. If they left a chink visible from the streets, an impertinent air raid warden or policeman would be knocking at their door, or ringing the bell with its new touch of luminous paint. There was an understandable tendency to neglect skylights and back windows. Having struggled with drawing pins and thick paper, or with heavy black curtains, citizens might contemplate going out after supper - and then reject the idea and settle down for a long read and an early night.

For to make one's way from back street or suburb to the city centre was a prospect fraught with depression and even danger. In September 1939 the total of people killed in road accidents increased by nearly one hundred per cent. This excludes others who walked into canals, fell down steps, plunged through glass roofs and toppled from railway platforms. A Gallup Poll published in January 1940 showed that by that stage about one person in five could claim to have sustained some injury as a result of the blackout - not serious, in most cases, but it was painful enough to walk into trees in the dark, fall over a kerb, crash into a pile of sandbags, or merely cannonade off a fat pedestrian.