Anti-Semitism in Britain

The unpopularity of the Jewish community in modern times and the growth of anti-Semitism, can be traced back to an event that took place in Russia. On 13th March, 1881, Tsar Alexander II was assassinated by the People's Will group. One of those convicted of the attack was a young Jewish woman, Gesia Gelfman. Along with Sophia Perovskaya, Andrei Zhelyabov, Nikolai Kibalchich, Nikolai Rysakov, and Timofei Mikhailov, Gelfman was sentenced to death. (1)

The People's Will contacted the Russian government and claimed they would call off the terror campaign if the Russian people were granted a constitution that provided free elections and an end to censorship. Tsar Alexander III rejected this proposal and instead decided to blame the Jews for his father's death. The government claimed that 30% of those arrested for political crimes were Jewish, as were 50% of those involved in revolutionary organisations, even though Jews were a mere 5% of the overall population. (2)

As one Jewish historian has pointed out, the assassination of Alexander II heralded an outbreak of Anti-Semitism: "Within a few weeks, impoverished and vulnerable Jewish communities suffered a wave of pogroms - random mob attacks on their villages and towns, which the authorities were unwilling to prevent and were accused of unofficially instigating. In 1881, pogroms were recorded in 166 Russian towns." (3)

Over the next 25 years, more than a third of Russia's Jews left the country, many of them settling in Britain. These people received a hostile reception from the right-wing press. (4) Even traditional trade unions were hostile to the Jewish immigrants. Ben Tillett, described them as the "dregs and scum of the continent" who made overcrowded slums "more foetid, putrid and congested". William Morris, Eleanor Marx, Ernest Belfort Bax and other members of the Socialist League defended them and encouraged Jewish workers to form their own unions. (5)

Three times during the 1890s, the TUC passed resolutions calling for immigration controls. A group of Jewish trade unionists, led by Joseph Finn, published a document called Voice from the Aliens to counter one such resolution at the 1895 congress. "It is, and always has been, the policy of the ruling class to attribute the sufferings and miseries of the masses (which are natural consequences of class rule and class exploitation) to all sorts of causes except the real ones. The cry against the foreigner is not merely peculiar to England, it is international. Everywhere he is the scapegoat for other's sins. Every class finds in him an enemy. So long as the Anti-Alien settlement in this country was confined to politicians, wire-pullers, and to individual working-men, we, the organised aliens, took no heed; but when this ill-founded sentiment has been officially expressed by the organised working men of England, then we believe that it is time to lift our voices and argue the matter out."

The document pointed out: "The average annual immigration of Aliens in England according to the report of the Board of Trade for 1891-1893 has been 24,688, whilst the average annual emigration is put down by the Dictionary of Statistics at 164,000. In face of these figures, we repeat our argument. If immigration over-guts the market then emigration must logically relieve it. And, seeing that emigration is more than six times the immigration, we cannot see why England should cry out so loudly about the foreigner."

Finn states that: "We, the Jewish workers, have been spoken of as a blighting blister upon the English trades and workers, as men to whose hearts it is impossible to appeal, and were it not for us, the conditions of the native worker would be much improved. He would have plenty of work, good wages and what not. Well, let us look at the facts, let us examine the condition of such workers with whom the Jew never comes in contact, such as the agricultural labourer, the docker, the miner, the weaver, the chainmaker, shipbuilder, bricklayer and many others. Examine their condition, dear reader, and answer: is there any truth in the remark that we are a 'blighting blister' upon the English worker?” (6)

Despite these logical arguments The Daily Mail continued its campaign against the arrival of Jews being persecuted in Russia: "On 2nd February, 1900, a British liner called the Cheshire moored at Southampton, carrying refugees from anti-semitic pogroms in Russia... There were all kinds of Jews, all manner of Jews. They had breakfasted on board, but they rushed as though starving at the food. They helped themselves at will, they spilled coffee on the ground in wanton waste.... These were the penniless refugees and when the relief committee passed by they hid their gold, and fawned and whined, and in broken English asked for money for their train fare." (7)

British Brothers' League

Several Conservative Party members of the House of Commons from East London, including Major William Evans-Gordon (Stepney), Samuel Forde Ridley (Bethnal Green South West), Claude Hay (Hoxton), Walter Guthrie (Bow and Bromley), Spencer Charrington (Mile End) and Thomas Dewar (Tower Hamlets, St George) launched an anti-alien campaign in 1901. Two Jewish MPs, Harry Samuel (Limehouse) and Benjamin Cohen (Islington East) also called for restrictions on immigration. Evans-Gordon argued against "the settlement of large aggregations of Hebrews in a Christian land". In another article he argued that "east of Aldgate one walks into a foreign town" and the development of a separate community, "a solid and permanently distinct block - a race apart, as it were, in an enduring island of extraneous thought and custom". (8)

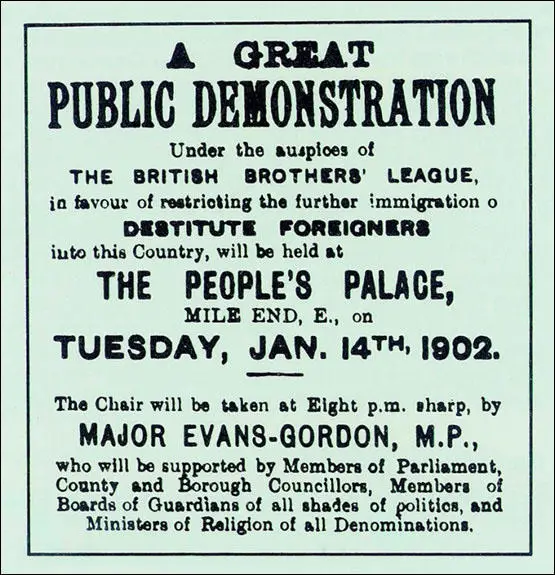

According to his biographer, Marc Brodie, Evans-Gordon "was instrumental in the establishment of" the British Brothers' League (BBL), "a purportedly working-class anti-immigration body". (9) Evans-Gordon and other Tory MPs in the area galvanised the poorer local populace into angry street marches calling for an end to Jewish immigration. It was stated that the government "would not have this country made the dumping ground for the scum of Europe" and complained that England should be "the heart of the Empire not the dustbin of Austria and Russia". (10)

William Stanley Shaw was elected President of the organisation. He later recalled "that the first manifesto of the British Brothers' League was issued in February, 1901, but we did not commence enrolling members until May, 1901." In the first year Shaw claimed that BBL had "between ten and twelve thousand members, of which some fifteen hundred had paid the sixpence subscription." (11)

Mancherjee Bhownagree, the Tory MP for Bethnal Green North-East, who had been born in India but had moved to London in 1882, also gave his support to the anti-immigrant campaign and endorsed "any action which might stop this undesirable addition to our population". Most members were "mostly local factory workers and unemployed, convinced by BBL propaganda that their precarious work situation, low pay, overcrowded housing and poor sanitation was caused by immigration. The BBL marched through impoverished East End districts, voicing working class concerns, but wealthier elements ran the organisation from its Gracechurch Street offices nestled comfortably within the City." (12)

The leaders of the British Brothers' League convinced many local workers that the influx of migrants willing to work long hours for low pay undermined their struggle for better conditions. Instead of unionising migrants, the BBL called for restriction of entry. The Liberal MP, Henry Norman of Wolverhampton South, also joined the campaign and advised other nations to "disinfect their own sewage". As a result of their campaign the BBL were able to present a petition to Parliament with 45,000 signatures, mostly collected in east London, calling for immigration control." (13)

Holding "Britain for the British" banners and Union Jacks, the British Brothers' League took part in intimidating marches through the East End. The Jewish Chronicle observed derisively that "there appears to be very little British and nothing brotherly in the new league." The 1900 General Election campaign saw several Conservative candidates stating their support of the British Brothers League. As a result "the brought into the House of Commons a cadre of Tory MPs representing East End constituencies who were committed to restricting immigration." (14)

Church leaders also joined the campaign against Jews (also referred to as Aliens). In 1902, the Bishop of Stepney, Cosmo Gordon Lang (later the Archbishop of Canterbury) had accused Jewish immigrants of only speaking three English words - "Board of Guardians". Lang went on to say: "I recognize the vigour and intelligence among the aliens but the fact remains that they are swamping whole areas once populated by English people and our churches are continually being left like islands in a sea of aliens." (15)

William Stanley Shaw, the original president of the British Brothers' League resigned in April 1902, and was replaced by Howard Vincent, the Conservative Party MP for Sheffied Central. He claimed that right-wing politicians had turned it into an anti-Semitic organisation. He pointed out in a letter to the East London Observer three months later that the "first condition that I made on starting the movement was the word 'Jew' should never be mentioned and that as far as possible the agitation should be kept clear of racial and religious animosity". He added that other members of the BBL were trying to make people believe that "alien" means "Jew" whereas he insisted it meant "foreigner". According to Shaw "religion had nothing to do with it". (16)

In a letter to the newspaper in September he explained his decision to resign in more detail. He criticised those Tory MPs who were exploiting the subject of immigration and questioned the reasons why "those noble personages who suddenly develop a burning interest in the troubles and perplexities of the masses." Shaw argued that the BBL had "started with the object of benefiting British workers" but had recently become "the pray of outside politicians". He went on to point out that "British workers should remember that this alien influx has been going on for twenty years, to a greater or lesser extent. It is no new discovery. The fault, too lies not with the immigrants in coming here, but with the British Government in allowing them to come. Do not blame the wrong people." (17)

1905 Alien Act

Major William Evans-Gordon was now the main figure in the British Brothers' League, an organisation that now had 12,000 members. Evans-Gordon toured eastern Europe to study the Jewish immigration question, and wrote of his journey in his book The Alien Immigrant (1903). It has been described as an "exhaustively researched and well-received treatise focused on the social political, and economic effects of the mass emigration of Eastern Europeans into Britain." (18) Evans-Gordon concluded his study with the words: "it is a fact that the settlement of large aggregations of Hebrews in a Christian land has never been successful". (19)

Members of the recently formed Labour Party and Jewish trade unionists formed the Aliens Defence League to counteract the British Brothers' League. Evans-Gordon responded by forming a committee of MPs pledged to vote for restriction (the parliamentary pauper immigration committee) and this played an important part in forcing the government to establish a royal commission on alien immigration in 1902. As a member of the commission, Evans-Gordon was "the individual who dominated the whole investigation". Many of the witnesses called by the commission were organized by the BBL. (20)

The commission's report was presented in August 1903 and recommended a range of measures to restrict immigration. It argued that: "Immigrants arrived impoverished, destitute and dirty; practised insanitary habits; spread infectious diseases; were a burden on the rates; dispossessed native dwellers; caused native tradesmen to suffer a loss of trade; worked for rates below the 'native workman'; included criminals, prostitutes and anarchists; formed a compact non-assimilating community, that didn't intermarry; and interfered with the observance of Christian Sunday." (21)

After the publication of this report the government, under pressure from right-wing elements in the Conservative Party, and reactionary newspapers such as the Daily Mail, to do something about immigration controls. Eventually, Arthur Balfour, the prime minister, agreed to introduce an Aliens Act. Aside from anti-semitic sentiments, the act was also driven by the economic and social unrest in the East End of London where most immigrants settled. According to the government, the undercutting of British labour was therefore a central driving force to the passing of the legislation. (22)

In a leading article on 11th December, 1903, The Jewish Chronicle protested that the proposed Alien Act really had nothing to do with the Jews, but was a protectionist measure intended to appease the working classes at a time of unemployment and so help to retain the seats of Conservative MPs. (23) In the next few weeks the newspaper published several articles showing that immigration was declining and pressure on the housing market was easing. (24)

The first attempt to pass the Alien Act in 1904 ended in failure. Howard Vincent, the president of the British Brothers League, complained that members of the Labour Party and the left-wing of the Liberal Party had blocked the measure: "To kill the bill by talk was the avowed object of the Radical obstructionists, and, thanks to them, Stepney and Whitechapel, Hoxton and Tower Hamlets, Poplar and Limehouse, Shoreditch and Bethnal Green, must continue for a while to suffer the evils of unrestricted alien immigration, driving the working-classes from employment and from home, and the townspeople into bankruptcy." However, Vincent claimed that Balfour had assured William Evans-Gordon and Samuel Forde Ridley, two members of the BBL, that he intended to try again to get the measure passed: "From every point of view I think a measure dealing with the subject is of great importance, and no time shall be lost in making an effort, and I think a more successful effort, to grapple with its difficulties." (25)

The novelist, Marie Corelli, gave her support to the campaign of the British Brothers' League: "The evils of overcrowding in London, as well as the large provincial cities, are steadily increasing, and it is hard to see why Great Britain should alone, out of all the countries in the world, be made a refuge for destitute foreigners. The size of the British Islands on the map, as compared with the rest of Europe, is so out of all proportion to the influx of alien population which annually floods our coasts, that this fact alone ought to be sufficient to press home to all reasoning and reasonable minds the necessity of enforcing legislation in such a way that a proper restriction may be set on the immigration of aliens to a country which has not sufficient room for the growth of its own people... Our first duty is to ourselves and the maintaining of our position with honour. British work, British wages and British homes should be among the first considerations of the British Government." (26)

When the Alien Bill was introduced again in 1905, Arthur Balfour claimed that the measure would save money for the country. "Why should we admit into this country people likely to become a public charge? Many countries which exclude immigrants have no Poor Laws they have not those great charities of which we justly boast. The immigrant comes in at his own peril and perishes if he cannot find a living. That is not the case here. From the famous statute of Elizabeth we have taken on ourselves the obligation of supporting every man, woman, and child in this country and saving them from starvation. Is the statute of Elizabeth to have European extension? Are we to be bound to support every man, woman, and child incapable of supporting themselves who choose to come to our shores? That argument seems to me to be preposterous. When it is remembered that some of these persons are a most undesirable element in the population, and are not likely to produce the healthy children... but are afflicted with disease either of mind or of body, which makes them intrinsically undesirable citizens, surely the fact that they are likely to become a public charge is a double reason for keeping them out of the country." (27)

Stuart Samuel, the Liberal Party MP for Whitechapel, accused the government of proposing legislation that would stop Jews who were suffering from religious persecution from entering the country. "The Prime Minister... had laid it down that we were bound by out historical past to refuse admission to the victims of religious persecution upon the ground that to admit them would cost this country a certain sum of money. That sordid and unworthy argument he believed the people of this country would not approve of.... If the right hon. Gentleman thought that he represented the opinions of the people of this country, why did he not appeal to them in that case? The right hon. Gentleman knew perfectly well that up and down the country the people were in favour of religious freedom.... said that if they refused asylum in this country to the victims of religious persecution and threw them back into the country where they were religiously persecuted, they were participating in the wrong." (28)

Balfour claimed that this legislation would help to protect the working-class from immigrants willing to accept lower-wages. This idea was completely rejected by Kier Hardie, the leader of the Labour Party: "The right hon. Gentleman (Arthur Balfour) replied that the Bill proposed to give protection to underpaid British labour against the competition of foreigners. At the present time the workman knew he had no such protection, but if this Bill became law he would relatively be worse off than he was now, because he would have a nominal protection. He would be more liable to competition under the Bill than he was now. Under the Bill no poor workman could come in unless he brought a contract of employment with him, and therefore the whole machinery would be set up for importing foreign workmen under a contract of employment, and it would be easier for the employers who wanted to obtain a gang of foreign workmen to obtain them. Consequently a British workman who was being threatened with a strike or a lock-out would find his position worse under the Bill than he did at present. The Government, had no right to so legislate as to give the employer an unfair advantage over his workman during a trade dispute." (29)

Although the word "Jew" was absent from the legislation, Jews formed the vast bulk of the "aliens" category. Speaking during the committee stage of the Alien Bill, Balfour argued that Jews should be prevented from arriving in Britain because they were not "to the advantage of the civilisation of this country... that there should be an immense body of persons who, however patriotic, able and industrious, however much they threw themselves into the national life, they are a people apart and not only had a religion differing from the vast majority of their fellow countrymen but only intermarry amongst themselves." (30)

The Liberal Party believed that the Alien Act was popular with the electorate and decided not to oppose the bill with any great effort. However, a couple of its more left-wing members, Charles Trevelyan and Charles Wentworth Dilke did warn of the dangers of this legislation. All four Jewish MPs who represented the Conservative Party, including Benjamin Cohen and Harry Samuel, voted for the legislation. Of the four Jewish Liberal MPs, one abstained and three voted against. (31)

As Geoffrey Alderman, the author of Modern British Jewry (1998) has pointed out the role of Chief Hermann Adler in this dispute: "It was not at the Jewish Board of Deputies that the principle of the legislation was condemned, but at the Jewish Working Men's Club, Great Alie Street, Aldgate, and by the Jewish Socialist-Zionist party, Poale Zion... Chief Rabbi Adler was reluctant to condemn it... At the general election of January 1906, in at least one constituency (Leeds Central) Adler's influence was discreetly employed by the Conservative interest." (32)

The Aliens Act was given royal assent in August 1905. With a great deal of justification, William Evans-Gordon was regarded by Chaim Weizmann, later the first president of Israel, as the "father of the Aliens Act". (33) It was the first time the government introduced immigration controls and registration, and gave the Home Secretary overall responsibility for immigration and nationality matters. The government argued that the act was designed to prevent paupers or criminals from entering the country and set up a mechanism to deport those who slipped through. Alfred Eckhard Zimmern, was one of many who opposed the legislation as being anti-Semitic, commented: "It is true that it does not specify Jews by name and that it is claimed that others besides Jews will be affected by the Act, but that is only a pretence." (34)

1906 General Election

In the 1906 General Election Tory MPs attempted to use the subject of immigration to win them votes. David Hope Kyd, the prospective MP for Whitechapel, told the electorate that Stuart Samuel, the sitting member, was pro-alien and it was "no good sending to Parliament a man who stands up... for the foreign Jews" and what was needed was "someone who could speak for the English in Whitechapel." (35) He was not the only Tory to mount a racist campaign as they appealed to "the British working man" to vote against "Pro-Alien Radical Jews" and "push back this intolerable invasion". (36)

The passing of the Alien Act did not help the Conservative Party in the 1906 General Election. The Liberal Party won 397 seats (48.9%) compared to the Conservative Party's 156 seats (43.4%). The Labour Party, led by Keir Hardie did well, increasing their seats from 2 to 29. In the landslide victory, the prime minister, Arthur Balfour, also lost his seat. Others who failed to get elected included supporters of the British Brothers League such as Samuel Forde Ridley (Bethnal Green South West), Walter Guthrie (Bow and Bromley), Thomas Dewar (Tower Hamlets, St George), Claude Hay (Hoxton), Harry Samuel (Limehouse), Benjamin Cohen (Islington East) and Mancherjee Bhownagree (Bethnal Green North-East). In Whitechapel, its Jewish MP, Stuart Samuel, who campaigned against the legislation, increased his majority over his racist opponent, David Hope Kyd. Margot Asquith wrote: "When the final figures of the Elections were published everyone was stunned, and it certainly looks as if it were the end of the great Tory Party as we have known it." (37)

However, the Alien Act was not repealed by the new Liberal government. As David Rosenberg has pointed out: "The Alien's Act drastically reduced the numbers of Jews seeking economic betterment in Britain who were permitted to enter; it also prevented greater numbers of asylum-seekers, escaping harrowing persecution, from finding refuge. In 1906, more than 500 Jewish refugees were granted political asylum. In 1908 the figure had fallen to twenty and by 1910, just five. During the same period, 1,378 Jews, who had been permitted to enter as immigrants but were found to be living on the streets without any visible means of support, had been rounded up and deported back to their country of origin." (38)

Russian Revolution and the Jews

This campaign against the Jews intensified after the Russian Revolution in 1917. On 5th June, 1918, The Daily Mail launched a campaign against the Home Office's aliens policy. Other sections of Fleet Street quickly joined the bandwagon. This forced the government to take strong measures against those people fleeing from Russia. This included a recommendations of 257 fresh internments and 220 repatriations. (39)

The connection between Jews and international communism was stressed by Winston Churchill in an article in The Illustrated Sunday Herald. He accused them of being part of "this worldwide conspiracy for the overthrow of civilization and the reconstruction of society on the basis of arrested development, of envious malevolence, and impossible equality." He added: "This movement amongst the Jews is not new... It has been the mainspring of every subversive movement during the 19th Century; and now at last this band of extraordinary personalities has gripped the Russian people by the hair of their heads and have become practically the undisputed masters of that enormous empire."

Churchill argued that the revolution would not have taken place without the involvement of Jewish leaders: "There is no need to exaggerate the part played in the creation of Bolshevism and in the actual bringing about of the Russian Revolution, by these international and for the most part atheistic Jews, it is certainly a very great one; it probably outweighs all others. With the notable exception of Lenin, the majority of the leading figures are Jews." (40)

Right-wing newspapers continued to publish propaganda against the Jewish community. In November 1932, the Daily Express, granted space for a sizeable article by Joseph Goebbels, head of the Berlin section of the Nazi Party, and later its Minister of Propaganda, in which he set out his party's case against the Jews. The newspaper justified its action by saying it gave "utmost freedom of expression to both sides of all vital social and political issues." (41)

Even literary figures on the left criticised the Jews in Britain during the 1930s. H. G. Wells claimed that Jewish culture was narrow and racially egotistical, and that Jewish insistence on separation provided a justification for anti-Semitism. "It may not be a bad thing if they (the Jews) thought themselves out of existence altogether." George Bernard Shaw offered the following advice for Jews: "Those Jews who still want to be the chosen race - chosen by the late Lord Balfour - can go to Palestine and stew in their own juice. The rest had better stop being Jews and start being human beings." (42)

References

(1) Cathy Porter, Fathers and Daughters: Russian Women in Revolution (1976) page 276

(2) Michael Burleigh, Blood & Rage: A Cultural History of Terrorism (2008) page 58

(3) David Rosenberg, Battle for the East End: Jewish Responses to Fascism in the 1930s (2011) page 20

(4) Lionel Morrison, A Century of Black Journalism in Britain (2007) page 170

(5) David Rosenberg, The Guardian (4th March, 2015)

(6) Joseph Finn, Voice from the Aliens (1895)

(7) The Daily Mail (3rd February, 1900)

(8) Colin Holmes, Anti-Semitism in British Society, 1876-1939 (1979) page 27

(9) Marc Brodie, William Evans-Gordon: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004)

(10) David Rosenberg, Battle for the East End: Jewish Responses to Fascism in the 1930s (2011) page 23

(11) East London Observer (19th October, 1901)

(12) David Rosenberg, The Guardian (4th March, 2015)

(13) David Rosenberg, Rebel Footprints: A Guide to Uncovering London's Radical History (2015) page 94

(14) David Cesarani, The Jewish Chronicle and Anglo-Jewry, 1841–1991 (1994) page 74

(15) Stephen Aris, But there are no Jews in England (1970) page 32

(16) Colin Holmes, Anti-Semitism in British Society, 1876-1939 (1979) page 94

(17) William Stanley Shaw, letter to the East London Observer (27th September, 1902)

(18) Lara Trubowitz, Civil Antisemitism, Modernism, and British Culture, 1902-1939 (2012) pages 29-30

(19) William Evans-Gordon, The Alien Immigrant (1903) page 248

(20) Marc Brodie, William Evans-Gordon: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004)

(21) David Rosenberg, Rebel Footprints: A Guide to Uncovering London's Radical History (2015) pages 94-95

(22) Bernard Gainer, The Alien Invasion: The Origins of the Aliens Act of 1905 (1972) pages 19-20

(23) The Jewish Chronicle (11th December, 1903)

(24) David Cesarani, The Jewish Chronicle and Anglo-Jewry, 1841–1991 (1994) page 99

(25) East London Observer (27th August, 1904)

(26) Marie Corelli, letter in The Morning Post (2nd May 1905)

(27) Arthur Balfour, speech in the House of Commons (2nd May 1905)

(28) Stuart Samuel, speech in the House of Commons (10th July, 1905)

(29) Kier Hardie, speech in the House of Commons (10th July, 1905)

(30) Geoffrey Alderman, Modern British Jewry (1998) page 133

(31) House of Commons vote on the Alien Act (5th May, 1905)

(32) Geoffrey Alderman, Modern British Jewry (1998) page 137

(33) Bernard Gainer, The Alien Invasion: The Origins of the Aliens Act of 1905 (1972) page 182

(34) Alfred Eckhard Zimmern, The Economic Journal (April, 1911)

(35) Colin Holmes, Anti-Semitism in British Society, 1876-1939 (1979) page 28

(36) Paul Thompson, Socialists, Liberals and Labour: the Struggle for London, 1885–1914 (1967) page 29

(37) Margot Asquith, The Autobiography of Margot Asquith (1962) page 245

(38) David Rosenberg, Battle for the East End: Jewish Responses to Fascism in the 1930s (2011) page 114

(39) David Cesarani, The Internment of Aliens in the 20th Century (1993) page 61

(40) Winston Churchill, The Illustrated Sunday Herald (8th February, 1920)

(41) The Daily Express (6th November, 1932)

(42) David Rosenberg, Battle for the East End: Jewish Responses to Fascism in the 1930s (2011) page 43

John Simkin