Domestic System

In the 18th Century the production of textiles was the most important industry in Britain. As A. L. Morton, the author of A People's History of England (1938) has pointed out: "Though employing far fewer people than agriculture, the clothing industry became the decisive feature of English economic life, what which marked it off sharply from that of most other European countries and determined the direction and speed of its development." (1)

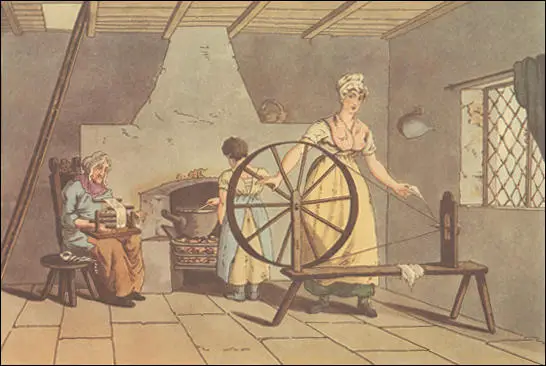

During this period most of the cloth was produced in the family home and therefore became known as the domestic system. (2) There were three main stages to making cloth. Carding was usually done by children. This involved using a hand-card that removed and untangled the short fibres from the mass. Hand cards were essentially wooden blocks fitted with handles and covered with short metal spikes. The spikes were angled and set in leather. The fibres were worked between the spikes and, be reversing the cards, scrapped off in rolls (cardings) about 12 inches long and just under an inch thick. (3)

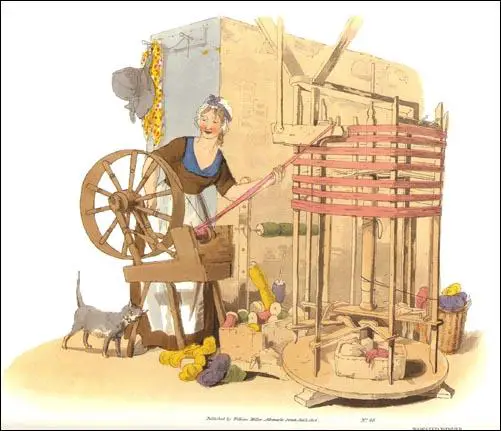

The mother turned these cardings into a continuous thread (yarn). The distaff, a stick about 3 ft long, was held under the left arm, and the fibres of wool drawn from it were twisted spirally by the forefinger and thumb of the right hand. As the thread was spun, it was wound on the spindle. The spinning wheel was invented in Nuremberg in the 1530s. It consisted of a revolving wheel operated by treadle and a driving spindle. (4)

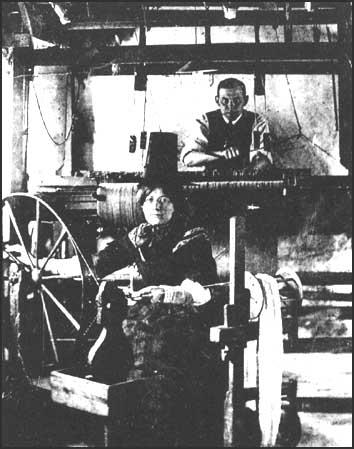

Finally, the father used a handloom to weave the yarn into cloth. The handloom was brought to England by the Romans. The process consisted of interlacing one set of threads of yarn (the warp) with another (the weft). The warp threads are stretched lengthwise in the weaving loom. The weft, the cross-threads, are woven into the warp to make the cloth. Daniel Defoe, the author of A Tour Through the Whole Island of Great Britain (1724) "Among the manufacturers' houses are likewise scattered an infinite number of cottages or small dwellings, in which dwell the workmen which are employed, the women and children of whom, are always busy carding, spinning, etc. so that no hands being unemployed all can gain their bread, even from the youngest to the ancient; anyone above four years old works." (5)

The woven cloth was sold to merchants called clothiers who visited the village with their trains of pack-horses. These men became the first capitalists. To increase production they sometimes they sold raw wool to the spinners. They also sold yarn to weavers who were unable to get enough from family members. Some of the cloth was made into clothes for people living in this country. However, a large amount of cloth was exported to Europe. (6)

The production and export of cloth continued to grow. In order to protect the woolen cloth industry the import of cotton goods was banned in 1700. In the time of Charles II the export of woolen cloth was estimated to be valued at £1 million. By the beginning of the 18th century it was almost £3 million and by 1760 it was £4 million. However, this was all changed when James Hargreaves invented the spinning-jenny in 1764. The machine used eight spindles onto which the thread was spun from a corresponding set of rovings. By turning a single wheel, the operator could now spin eight threads at once. (7)

George Walker pointed out: "The manufacture of cloth affords employment to the major part of the lower class of people in the north-west districts of the West Riding of Yorkshire. These cloth-makers reside almost entirely in the villages, and bring their cloth on market-days for sale in the great halls erected for that purpose at Leeds and Huddersfield." (8)

Samuel Bamford was involved in the domestic system: "The farming was generally done by the husband and other males of the family, whilst the wife and daughters attended the churning, cheese-making, and household work; and when that was finished, they busied themselves with carding and spinning wool or cotton, as well as forming it into warps for the looms. The husbands and sons would next, at times when farm labour did not call them, size the warp, dry it, and beam it in the loom. A farmer would generally have three or four looms in the house, and then - what with the farming, the housework, the carding, spinning and weaving - there was ample employment for the family." (9)

According to William Radcliffe the standard of living of people improved during this period: "In the year 1770... the father of the family would earn from eight to ten shillings at his loom, and his sons... along side of him, six to eight shillings per week... it required six to eight hands to prepare and spin yarn for each weaver... every person from the age of seven to eighty years (who retained their sight and could move their hands) could earn... one to three shillings per week". (10) As one observer pointed out: "Their little cottages seemed happy and contended... it was seldom that a weaver appealed to the parish for relief." (11)

In 1733 John Kay devised the Flying Shuttle. By pulling a string, the shuttle was rapidly sent from one side of the loom to the other. This invention not only doubled the speed of cloth production, but also enabled large looms to be operated by one person. When Kay showed his invention to the local weavers it received a mixed reception. Some saw it as a way to increase their output. Other weavers were very angry as they feared that it would put them out of work. (12)

By the 1760s, weavers all over Britain were using the Flying Shuttle. However, the increased speed of weaving meant there was now a shortage of yarn. Kay therefore set himself the task of improving the traditional spinning-wheel. When local spinners heard about Kay's plans, his house was broken into and the machine he was working on was destroyed.

Kay was so upset by what had, happened that he left Britain and went to live in France. Others continued with his work and eventually James Hargreaves, a weaver from Blackburn, invented the Spinning-jenny. By turning a single wheel, the operator could now spin eight threads at once. Later, improvements were made that enabled this number to be increased to eighty. By the end of the 1780s there were an estimated 20,000 of these machines being used in Britain. (7)

Adam Hart-Davis has explained the way the new machine worked: "Several spinning machines were designed at about this time, but most of them tried to do the stretching and the spinning together. The problem is that the moment you start twisting the roving you lock the fibres together. Arkwright's idea was to stretch first and then twist. The roving passed from a bobbin between a pair of rollers, and then a couple of inches later between another pair that were rotating at twice the speed. The result was to stretch the roving to twice its original length. A third pair of rollers repeated the process... Two things are obvious the moment you see the wonderful beast in action. First, there are 32 bobbins along each side of each end of the water frame - 128 on the whole machine. Second, it is so automatic that even I could operate it." (13)

The woven cloth was sold to merchants called clothiers who visited the village with their trains of pack-horses. Some of the cloth was made into clothes for people living in this country. However, a large amount of cloth was exported. In the last quarter of the 18th century, the spinning of thread and the making of cloth was the single most important industry in Britain. (14)

As A. L. Morton has pointed out: "Once the production of cloth was carried out on a large scale for the export market the small independent weaver fell inevitably under the control of the merchant who alone had the resources and the knowledge to tap the market... The clothier, as the wool capitalist came to be called, began by selling yarn to the weavers and buying back the cloth from them. Soon the clothiers had every process under control. They bought raw wool, gave it out to the spinners, mostly women and children working in their cottages, collected it again, handed it on to the weavers, the dyers, the fullers and the shearmen." (15)

Primary Sources

(1) Daniel Defoe, A Tour Through the Whole Island of Great Britain (1724)

The nearer we came to Halifax, we found the houses thicker, and the villages greater. The sides of hills, which were very steep, were spread with houses; for the land being divided into small enclosures, that is to say, from two acres to six or seven acres each, seldom more; every three or four pieces of land had a house belonging to it.

Their business is the clothing trade. Each clothier must keep a horse, perhaps two, to fetch and carry for the use of his manufacture, to fetch home his wool and his provisions from the market, to carry his yarn to the spinners, his manufacture to the fulling mill, and, when finished, to the market to be sold.

Among the manufacturers' houses are likewise scattered an infinite number of cottages or small dwellings, in which dwell the workmen which are employed, the women and children of whom, are always busy carding, spinning, etc. so that no hands being unemployed all can gain their bread, even from the youngest to the ancient; anyone above four years old works.

(2) William Radcliffe, The Origin of the New System of Manufacture (1828) page 59

In the year 1770... the father of the family would earn from eight to ten shillings at his loom, and his sons... along side of him, six to eight shillings per week... it required six to eight hands to prepare and spin yarn for each weaver... every person from the age of seven to eighty years (who retained their sight and could move their hands) could earn... one to three shillings per week.

(3) Richard Guest, A History of the Cotton Manufacture (1823)

The cotton, after being picked and cleaned, was spread upon a hand card, and was brushed, scraped or combed with the other, until the fibres of the cotton went in one direction; it was then taken off in soft fleecy rolls, about twelve inches long, and three quarters of an inch in diameter. These rolls, called cardings, were converted into a coarse thread, by twisting one end to the spindle of a hand-wheel, turning the wheel which moved the spindle with the right hand, and at the same time drawing out the carding with the left.

(4) Samuel Bamford, Early Days (1849)

The farming was generally done by the husband and other males of the family, whilst the wife and daughters attended the churning, cheese-making, and household work; and when that was finished, they busied themselves with carding and spinning wool or cotton, as well as forming it into warps for the looms. The husbands and sons would next, at times when farm labour did not call them, size the warp, dry it, and beam it in the loom. A farmer would generally have three or four looms in the house, and then - what with the farming, the housework, the carding, spinning and weaving - there was ample employment for the family.

(5) George Walker, The Costume of Yorkshire (1814)

The manufacture of cloth affords employment to the major part of the lower class of people in the north-west districts of the West Riding of Yorkshire. These cloth-makers reside almost entirely in the villages, and bring their cloth on market-days for sale in the great halls erected for that purpose at Leeds and Huddersfield.

Student Activities

Child Labour Simulation (Teacher Notes)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)

The Luddites: 1775-1825 (Answer Commentary)

The Plight of the Handloom Weavers (Answer Commentary)

Road Transport and the Industrial Revolution (Answer Commentary)