Sándor Ferenczi

Sándor Fränkel (later changed to Ferenczi), the son of Baruch Fränkel and Rosa Eibenschütz, both Polish Jews, was born in Budapest on 7th July 1873. His father was a bookseller and publisher. According to Peter Gay, "he wrestled all his life with his insatiable appetite for love; as one of eleven children, with his father dying young and his mother busy with the store and her sizable brood, he felt from the start sadly deprived of affection." (1) Lou Andreas-Salomé, who became very close to Ferenczi, claimed that "as a child he suffered under inadequate appreciation of his accomplishments". (2)

Ferenczi studied medicine in Vienna in the early 1890s and settled down in Budapest to practice as a psychiatrist. He first became aware of Sigmund Freud when he read his book, The Interpretation of Dreams in 1900. The book is Freud's most original work. "Freud believed that in his opinion, he had done what no person before him had been able to do: break the code of dreams. He knew this was an important achievement in its own right; in addition, he was convinced that it unlocked the key to understanding and treating neurosis. If a therapist did not interpret dreams, Freud had come to believe, he or she was not doing psychoanalysis." (3)

Ferenczi pupil and friend the Hungarian psychoanalyst Michael Balint, later recalled that "Ferenczi bought a stop watch and no one was safe from him. Whomever he ran into in the Budapest coffee houses - novelists, poets, painters, the hat-check girl, waiters, etc. - was subjected to the association experiment". (4) In January 1908 Ferenczi wrote to Freud for an interview. Freud invited Ferenczi to meet him at his house. (5)

Wednesday Psychological Society

Although he came under attack for the ideas expressed in his books, Freud had a small loyal group of followers. They used to meet on Wednesday evenings and became known as the "Wednesday Psychological Society". Wilhelm Stekel claimed that it was his idea to form this group: "Gradually I became known as a collaborator of Freud. I gave him the suggestion of founding a little discussion group; he accepted the idea, and every Wednesday evening after supper we met in Freud's home... These first evenings were inspiring." (6)

Each week someone would present a paper and, after a short break for black coffee and cakes, a discussion would be held. Over the years to group included Sándor Ferenczi, Alfred Adler, Otto Rank, Max Eitingon, Wilhelm Stekel, Karl Abraham, Hanns Sachs and Fritz Wittels. It was clear that Freud was the dominant character in the group that were mostly Jews. Hanns Sachs said he was "the apostle of Freud who was my Christ". Another member said "there was an atmosphere of the foundation of a religion in that room. Freud himself was its new prophet... Freud's pupils - all inspired and convinced - were his apostles." Another member remarked that the original group was "a small and daring group, persecuted now but bound to conquer the world". (7) Fritz Wittels argued that Freud did not like members of his group to be too intelligent: "It did not matter if the intelligences were mediocre. Indeed, he had little desire that these associates should be persons of strong individuality, that they should be critical and ambitious collaborators. The realm of psychoanalysis was his idea and his will, and he welcomed anyone who accepted his views. What he wanted was to look into a kaleidoscope lined with mirrors that would multiply the images he introduced into it." (8)

The Wednesday meetings sometimes ended in conflict. However, Freud was very good at controlling the situation: "His diplomatic skill in modifying both his own demands and those of rivals was married to a determined effort to remain scientifically detached. Time and again his cool voice and calming influence broke into heated discussions and a volcanic situation was checked before it erupted. Considerable wisdom and tolerance marked many of his utterances and occasionally there was a tremendous sense of a figure, Olympian beside the pigmies around him, who quietened the waters with the wand of reason. Unfortunately, this side of Freud's character was heavily qualified by another. When someone put forward a proposition which seriously disturbed his own views, he first found it hard to accept and then became uneasy at this threat to the scientific temple he had so painfully built with his own hands." (9)

Freud originally found Wilhelm Stekel's ideas concerning dream symbolism interesting. He was also intuitive and indefatigable and entertaining company. However, he alienated members of the group with his boastfulness and his unscrupulousness in the use of scientific evidence. (10) Ernest Jones, who was present at some of these meetings claimed that Stekel had a "serious flaw in his character that rendered him unsuitable for work in an academic field: he had no scientific conscience at all." (11) On one occasion Stekel commented that a dwarf on the shoulder of a giant could see further than the giant himself. Freud replied: "That may be true, but a louse on the head of an astronomer does not." (12)

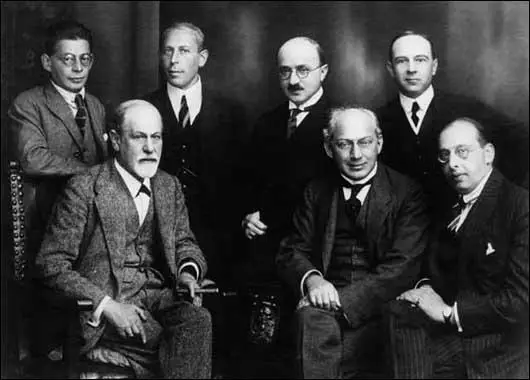

Seated, left to right, Sigmund Freud, Sándor Ferenczi and Hanns Sachs.

Sigmund Freud also clashed with Alfred Adler who openly questioned Freud's fundamental thesis that early sexual development is decisive for the making of character. Adler forcefully evolved a distinctive family of ideas. According to Peter Gay, the author of Freud: A Life for Our Time (1989), "Adler... secured an ascendancy among his colleagues second only to Freud." However, Freud disliked his socialist approach to the subject, "as a Socialist and social activist interested in the amelioration of humanity's lot through education and social work." (13) Freud once told Karl Abraham that "politics spoils the character". (14)

Sándor Ferenczi and Sigmund Freud

Sándor Ferenczi and Sigmund Freud became good friends. In the summer of 1908, they were so close that Freud arranged to have Ferenczi stay at a hotel near the family in Berchtesgaden. "Our house is open to you. But you should keep your freedom." (15) By October 1909, he began to head his letters to Ferenczi "Dear Friend". This was something he only did with a small number of people. (16)

In the summer of 1910 the two men went on holiday together in Sicily. Freud accused Ferenczi of turning him into a "father figure". He told him that while he looked back at the time in his company with "warm and sympathetic feelings," he "wished that you had torn yourself from your infantile role to place yourself next to me as an equal companion - which you did not succeed in doing." (17)

Despite these comments, Freud often addressed Ferenczi in his letters as if he was his son: "I am of course familiar with your 'complex troubles', and must admit I should prefer to have a self-confident friend, but when you make such difficulties then I have to treat you as a son. Your struggle for independence need not take the form of alternating between rebellion and submission. I think you are also suffering from the fear of complexes that has got associated with Jung's complex-mythology. A man should not strive to eliminate his complexes but to get into accord with them: they are legitimately what directs his conduct in the world." (18)

Ernest Jones claimed that Ferenczi was "the senior member of the group, the most brilliant member, and the one who stood closest to Freud". He pointed out: "What we saw was the sunny, benevolent, inspiring leader and friend. He had a great charm for men, though less so for women. He had a warm and lovable personality and a generous nature. He had a spirit of enthusiasm and devotion which he also expected and aroused in others. He was a highly gifted analyst with a remarkable flair for divining the manifestations of the unconscious. He was above all an inspiring lecturer and teacher." (19)

Visit to North America

Granville Stanley Hall, the President of Clark University, in Worcester, Massachusetts, had done much to popularize psychology, especially child psychology, in in the United States, and was the author of Adolescence: Its Psychology and Its Relations to Physiology, Anthropology, Sociology, Sex, Crime, Religion and Education (1904). Hall was a great supporter of Freud and in December, 1908, he invited him to deliver a series of lectures at the university. Freud invited Sándor Ferenczi and Carl Jung to accompany him on the trip. (20)

In August 1909, Ferenczi, Freud and Jung sailed to America. Ernest Jones travelled from Toronto, where he was working, to join them. While watching the waving crowds from the deck of his ship as it docked in New York, he turned to Jung and said, "Don't they know we're bringing them the plague?" (21) The following month Freud gave five lectures in German. He later recalled: "At that time I was only fifty-three. I felt young and healthy, and my short visit to the new world encouraged my self-respect in every way. In Europe I felt as though I were despised; but over there I found myself received by the foremost men as an equal." (22)

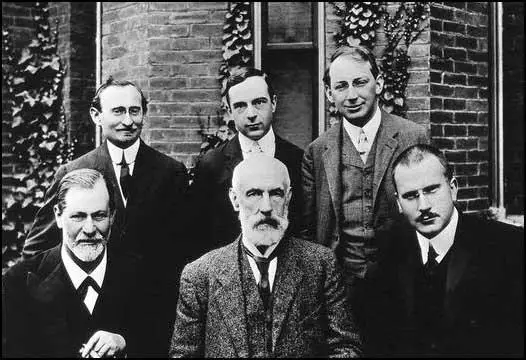

Front row, Sigmund Freud, Granville Stanley Hall and Carl Jung (September 1909)

Freud admitted that he had not expected the reception he received. "We found to our great surprise that the unprejudiced men in that small but reputable university knew all the psychoanalytic literature... In prudish America one could, at least in academic circles, freely discuss and scientifically treat everything that is regarded as improper in ordinary life.... Psychoanalysis was not a delusion any longer; it had become a valuable part of reality." (23)

Dispute with Carl Jung

During the boat trip to the United States Freud and Jung spent a lot of time discussing different psychological theories. Ernest Jones reported the two men began to argue about the importance of the Oedipus complex. Freud and Jung were also involved in the study of religion: "The revival of his interest in religion was to a considerable extent connected with Jung's extensive excursion into mythology and mysticism. They brought back opposite conclusions from their studies." (24)

Freud found this very disturbing as he treated Jung as his favourite son. He told him in a letter that "I am very fond of you" but he added "I have learned to subordinate that element." Freud admitted to Jung that it was his "egotistical intention, which I confess frankly" to "install" Jung as the person who would continue and complete "my work". As a "strong independent personality" he seemed best equipped for the task. (25)

Peter Gay, the author of Freud: A Life for Our Time (1989), explains the three reasons why he chose Jung as the future leader of the movement. "Jung was not Viennese, not old, and, best of all, not Jewish, three negative assets that Freud found irresistible." (26) Over and over, in his letters to his Jewish intimates, he praised Jung for doing "splendid, magnificent" work in editing, theorizing, or attacking the enemies of psychoanalysis. He told Sándor Ferenczi: "Now don't be jealous, and include Jung in your calculations. I am more convinced than ever that he is the man of the future." (27)

In a series of letters Jung questioned Freud's definition of libido. Jung believed that the word should not only stand for the sexual drives, but for a general mental energy. Freud wrote to Ferenzi that things were "storming and raging again" about Jung's "erotic and religious realm". (28) However, two weeks later he said he had "rapidly made it up with him, since, after all, I was not angry but only concerned." (29) Freud did what he could to keep Jung's loyalty. On 6th March, 1910, he wrote that his "dear son" should "rest easy" and told him of the great triumphs he would enjoy. "I leave you more to conquer than I could manage myself, all of psychiatry and the approval of the civilized world, which is accustomed to regard me as a savage." (30)

Jung continued to disagree with Freud and in a plea for autonomy he quoted the words of Friedrich Nietzsche: "One poorly repays a teacher if one remains only the pupil." (31) Freud responded with sadness: "If a third party should read this passage, he would ask me when I had undertaken to suppress you intellectually, and I would have to say: I do not know.... Rest assured of the tenacity of my affective interest, and keep thinking of me in a friendly way, even if you write only rarely." (32)

In May 1912 Freud and Jung became involved in a dispute over the meaning of the incest taboo. Freud now realised that his relationship was at breaking point. Freud now had a meeting with his loyal followers, Sándor Ferenczi, Ernest Jones, Otto Rank, Karl Abraham, Max Eitingon, and Hanns Sachs and it was decided to form a "united small body, designed... to guard the kingdom and policy of the master". (33)

The final break came when Jung made a speech at Fordham University where he rejected Freud's theories of childhood sexuality, the Oedipus complex and the role of sexuality in the formation of neurotic illness. In a letter to Freud, he argued that his vision of psychoanalysis had managed to win over many people who had hitherto been put off by "the problem of sexuality in neurosis". He said that he hoped that friendly personal relations with Freud would continue, but in order for that to happen he did not want resentment but objective judgments. "With me this is not a matter of caprice, but of enforcing what I consider to be true." (34)

Sándor Ferenczi died on 22nd May 1933

Primary Sources

(1) Ernest Jones, The Life and Work of Sigmund Freud (1961)

Ferenczi -.to use the name he and his tamily had adopted m place of their original surname, Fraenkel - was the senior member of the group, the most brilliant member, and the one who stood closest to Freud. On all counts, therefore, we must consider him first. Of his past history and of how he came to Freud I have already said something. Of the darker side of his life, hinted at above, we knew little until many years later when it could no longer be concealed. It was reserved for communion with Freud. What we saw was the sunny, benevolent, inspiring leader and friend. He had a great charm for men, though less so for women. He had a warm and lovable personality and a generous nature. He had a spirit of enthusiasm and devotion which he also expected and aroused in others. He was a highly gifted analyst with a remarkable flair for divining the manifestations of the unconscious. He was above all an inspiring lecturer and teacher.

Like all other human beings, however, he had his weaknesses. The only one apparent to us was his lack of critical judgement. He would propound airy, usually idealistic, schemes with little thought of their feasibility, but when his colleagues brought him down to earth he always took it good-naturedly. Two other qualities, of which we then knew little, were probably interrelated. He had an insatiable need to be loved, and when years later this met with inevitable frustration he gave way under the strain. Then, perhaps as a screen for his over-great love of others and the wish to be loved by them, he had developed a somewhat hard exterior in certain situations, which tended to degenerate into a masterful or even domineering attitude. This became more manifest in later years.

Ferenczi, with his open, childlike nature, his internal difficulties, and his soaring phantasies, made a great appeal to Freud. He was in many ways a man after his own heart. Daring and unrestrained imagination always stirred Freud. It was an integral part of his own nature to which he rarely gave full rein, since there it had been tamed by a sceptical vein quite absent in Ferenczi and a much more balanced judgement than his friend possessed. Still the sight of this unchecked imagination in others was something Freud could seldom resist, and the two men must have had enjoyable times together when there was no criticizing audience. At the same time, Freud's attitude toward Ferenczi was always fatherly and encouraging. He worked hard to get Ferenczi over his neurotic difficulties and to train him to deal with life to an extent he never felt impelled to with his own sons.

(2) Sigmund Freud, letter to Sándor Ferenczi (17th November, 1911)

You ask for a quick response to your emotional letter, and today I should very much like to work, being cheerful on account of good news which I shall presently tell you of. I shall answer you briefly and not say much new. I am of course familiar with your "complex troubles", and must admit I should prefer to have a self-confident friend, but when you make such difficulties then I have to treat you as a son. Your struggle for independence need not take the form of alternating between rebellion and submission. I think you are also suffering from the fear of complexes that has got associated with Jung's complex-mythology. A man should not strive to eliminate his complexes but to get into accord with them: they are legitimately what directs his conduct in the world.

Besides you are scientifically on the best road to make yourself independent. A proof of it is in your occult studies, which perhaps because of this striving contain an element of undue eagerness. Don't be ashamed of being for the most part more than I am willing to give. One must be glad when as a great exception someone manages to get on terms with himself without any help. You surely know the old saying: "The untoward things that don't happen are to be counted on the credit side."

Student Activities

References

(1) Peter Gay, Freud: A Life for Our Time (1989) page 187

(2) Lou Andreas-Salomé, Sa vie de confidente de Freud, de Nietzsche et de Rilke et ses écrits sur la psychanalyse, la religion et la sexualité (1958) page 193

(3) Michael Kahn, Basic Freud (2002) pages 155-156

(4) Peter Gay, Freud: A Life for Our Time (1989) page 188

(5) Sigmund Freud, letter to Sándor Ferenczi (8th July, 1908)

(6) Bernhard Handlbauer, The Freud-Adler Controversy (1998) page 13

(7) Frederick Crews, Freud: The Making of An Illusion (2017) page 621

(8) Fritz Wittels, Sigmund Freud (1924) page 134

(9) Vincent Brome, Freud and the Early Circle: The Struggles for Psycho-Analysis (1967) page 40

(10) Peter Gay, Freud: A Life for Our Time (1989) page 213

(11) Ernest Jones, The Life and Work of Sigmund Freud (1961) page 403

(12) Stephen Wilson, Sigmund Freud (1997) page 70

(13) Peter Gay, Freud: A Life for Our Time (1989) page 216

(14) Sigmund Freud, letter to Karl Abraham (1st January, 1913)

(15) Sigmund Freud, letter to Sándor Ferenczi (30th January, 1908)

(16) Peter Gay, Freud: A Life for Our Time (1989) page 188

(17) Sigmund Freud, letter to Sándor Ferenczi (2nd October, 1910)

(18) Sigmund Freud, letter to Sándor Ferenczi (17th November, 1911)

(19) Ernest Jones, The Life and Work of Sigmund Freud (1961) page 418

(20) Granville Stanley Hall, letter to Sigmund Freud (15th December, 1908)

(21) Christopher Turner, New York Times (23rd September, 2011)

(22) Sigmund Freud, Autobiography (1923) page 15

(23) Peter Gay, Freud: A Life for Our Time (1989) page 207

(24) Ernest Jones, The Life and Work of Sigmund Freud (1961) page 367

(25) Sigmund Freud, letter to Carl Jung (13th August, 1908)

(26) Peter Gay, Freud: A Life for Our Time (1989) page 202

(27) Sigmund Freud, letter to Sándor Ferenczi (29th December, 1910)

(28) Sigmund Freud, letter to Sándor Ferenczi (13th February, 1910)

(29) Sigmund Freud, letter to Sándor Ferenczi (3rd March, 1910)

(30) Sigmund Freud, letter to Carl Jung (6th March, 1910)

(31) Carl Jung, letter to Sigmund Freud (3rd March, 1910)

(32) Sigmund Freud, letter to Carl Jung (5th March, 1912)

(33) Ernest Jones, letter to Sigmund Freud (7th August, 1912)

(34) Carl Jung, letter to Sigmund Freud (11th November, 1912)