Grigori Rasputin

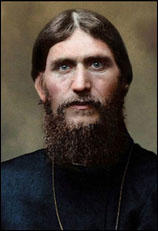

Grigori Yefimovich Rasputin, the son of a Russian peasant, was born in Pokrovskoye, Siberia, on 10th January 1869. His mother gave birth to seven other children but they all died in childbirth. His father, Yefim Rasputin, was described as "a typical Siberian peasant... chunky, unkempt and stooped". He served as an elder in the village church, and one local spoke of his "learned conversations and wisdom". (1)

Although he briefly attended school he failed to learn how to read or write. As a child he went with his parents to nearby monasteries and it is claimed that he wanted to become a monk. One biographer, Joseph T. Fuhrmann, points out: "Grigori's personality embodied divergent and contrasting strains - the religious seeker and the debauched hell-raiser." (2)

In 1886, Rasputin met the 20 year-old Praskovia Dubrovina. They were married five months later on 2nd February 1887, three weeks after his 18th birthday: "She was plump with dark eyes, small features and thick blonde hair. Though short, she was strong, an important asset in a wife expected to bear children while tackling the harvest." The first child was born the following year, but died at six months of scarlet fever. They then had twins, who both died of whooping cough. Another child also died but three children survived childhood: Dimitri (1895), Maria (1898) and Varya (1900). (3)

Rasputin became a "holy wanderer" and a visitor to holy sites. On his return he developed a small group of followers. He became a vegetarian and argued against drinking alcohol. He also built a chapel in his father's cellar. It was rumoured that female followers were ceremonially washing him before each meeting and that the group was involved self-flagellation and sexual orgies. (4)

Grigori Rasputin and the Royal Court

It has been claimed that he visited "Jerusalem, the Balkans and Mesopotamia". (5) He claimed he had special powers that enabled him to heal the sick and lived off the donations of people he helped. Rasputin also made money as a fortune teller. In about 1902 he travelled to the city of Kazan on the Volga river, where he acquired a reputation as a holy man. Despite rumors that Rasputin was having sex with some of his female followers, he gained the support of senior figures of the church and was given a letter of recommendation to Bishop Sergei, the rector of the St. Petersburg Theological Seminary. (6)

Soon after arriving in St. Petersburg in 1903, Rasputin met Hermogen, the Bishop of Saratov. He was impressed by Rasputin's healing powers and introduced him to Nicholas II and his wife, Alexandra Fedorovna. The Tsar's only son, Alexei, suffered from haemophilia (a disease whereby the blood does not clot if a wound occurs). When Alexei was taken seriously ill in 1908, Rasputin was called to the royal palace. He managed to stop the bleeding and from then on he became a member of the royal entourage. (7)

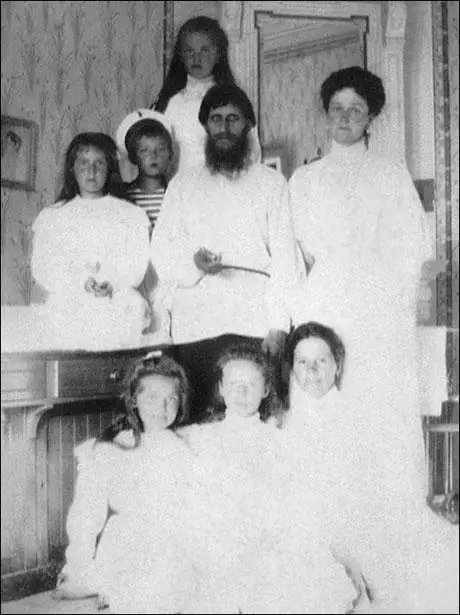

the family nurse Maria Ivanova Vishnyakova (1908)

The Tsarina was completely convinced by the supernatural power of Rasputin. "In their despair at the inability of orthodox medicine to overcome or alleviate the disease, the imperial couple turned with relief to Rasputin... She attached physical power to objects handled by Rasputin. She sent Rasputin's stick and comb to the tsar so that he might benefit from Grigori's vigour when attending ministerial councils." (8)

The Tsarina became very dependent on Rasputin. One one occasion, when he had to spend time outside St. Petersburg, she wrote: "How distraught I am without you. My soul is only at peace, I only rest, when you, my teacher, are seated beside me and I kiss your hands and lean my head on your blessed shoulders... Then I only have one wish: to sleep for centuries on your shoulders, in the embraces." (9)

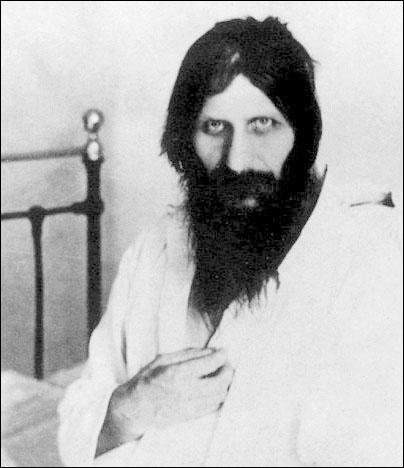

Ariadna Tyrkova, the wife of the British journalist, Harold Williams, wrote: "Throughout Russia, both at the front and at home, rumour grew ever louder concerning the pernicious influence exercised by the Empress Alexandra Feodorovna, at whose side rose the sinister figure of Gregory Rasputin. This charlatan and hypnotist had wormed himself into the Tsar’s palace and gradually acquired a limitless power over the hysterical Empress, and through her over the Sovereign. Rasputin’s proximity to the Tsar’s family proved fatal to the dynasty, for no political criticism can harm the prestige of Tsars so effectually as the personal weakness, vice, or debasement of the members of a royal house." (10)

Rasputin and the Triple Entente

On 12 July, 1914, a 33-year-old peasant woman named Chionya Guseva attempted to assassinate Grigori Rasputin by stabbing him in the stomach outside his home in Pokrovskoye. Rasputin was seriously wounded and a local doctor who performed emergency surgery saved his life. Guseva claimed to have acted alone, having read about Rasputin in the newspapers and believing him to be a "false prophet and even an Antichrist." (11)

In February 1914, Tsar Nicholas II accepted the advice of his foreign minister, Sergi Sazonov, and committed Russia to supporting the Triple Entente. Sazonov was of the opinion that in the event of a war, Russia's membership of the Triple Entente would enable it to make territorial gains from neighbouring countries. Sazonov sent a telegram to the Russian ambassador in London asking him to make clear to the British government that the Tsar was committed to a war with Germany. "The peace of the world will only be secure on the day when the Triple Entente, whose real existence is not better authenticated than the existence of the sea serpent, shall transform itself into a defensive alliance without secret clauses and publicly announced in all the world press. On that day the danger of a German hegemony will be finally removed, and each one of us will be able to devote himself quietly to his own affairs." (12)

In the international crisis that followed the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand, the Tsar made it clear that he was willing to go to war over this issue, Rasputin was an outspoken critic of this policy and joined forces with two senior figures, Sergei Witte and Pyotr Durnovo, to prevent the war. Durnovo told the Tsar that a war with Germany would be "mutually dangerous" to both countries, no matter who won. Witte added that "there must inevitably break out in the conquered country a social revolution, which by the very nature of things, will spread to the country of the victor." (13)

Sergei Witte realised that because of its economic situation, Russia would lose a war with any of its rivals. Bernard Pares met Witte and Rasputin several times in the years leading up to the First World War: "Count Witte never swerved from his conviction, firstly, that Russia must avoid the war at all costs, and secondly, that she must work for economic friendship with France and Germany to counteract the preponderance of England. Rasputin was opposed to the war for reasons as good as Witte's. He was for peace between all nations and between all religions." (14)

Outbreak of the First World War

On the outbreak of the First World War General Alexander Samsonov was given command of the Russian Second Army for the invasion of East Prussia. He advanced slowly into the south western corner of the province with the intention of linking up with General Paul von Rennenkampf advancing from the north east. General Paul von Hindenburg and General Erich Ludendorff were sent forward to meet Samsonov's advancing troops. They made contact on 22nd August, 1914, and for six days the Russians, with their superior numbers, had a few successes. However, by 29th August, Samsanov's Second Army was surrounded. (15)

General Samsonov attempted to retreat but now in a German cordon, most of his troops were slaughtered or captured. The Battle of Tannenberg lasted three days. Only 10,000 of the 150,000 Russian soldiers managed to escape. Shocked by the disastrous outcome of the battle, Samsanov committed suicide. The Germans, who lost 20,000 men in the battle, were able to take over 92,000 Russian prisoners. On 9th September, 1914, General von Rennenkampf ordered his remaining troops to withdraw. By the end of the month the German Army had regained all the territory lost during the initial Russian onslaught. The attempted invasion of Prussia had cost Russia almost a quarter of a million men. (16)

By December, 1914, the Russian Army had 6,553,000 men. However, they only had 4,652,000 rifles. Untrained troops were ordered into battle without adequate arms or ammunition. "Untrained troops were ordered into battle without adequate arms or ammunition. And because the Russian Army had about one surgeon for every 10,000 men, many wounded of its soldiers died from wounds that would have been treated on the Western Front. With medical staff spread out across a 500 mile front, the likelihood of any Russian soldier receiving any medical treatment was close to zero". (17)

Rasputin and Empress Alexandra

Tsar Nicholas II decided to replace Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolayevich Romanov as supreme commander of the Russian Army fighting on the Eastern Front. He was disturbed when he received the following information from General Alexei Brusilov: "In recent battles a third of the men had no rifles. These poor devils had to wait patiently until their comrades fell before their eyes and they could pick up weapons. The army is drowning in its own blood." (18)

Alexander Kerensky complained that: "The Tsarina's blind faith in Rasputin led her to seek his counsel not only in personal matters but also on questions of state policy. General Alekseyev, held in high esteem by Nicholas II, tried to talk to the Tsarina about Rasputin, but only succeeded in making an implacable enemy of her. General Alexseyev told me later about his profound concern on learning that a secret map of military operations had found its way into the Tsarina's hands. But like many others, he was powerless to take any action." (19)

As the Tsar spent most of his time at GHQ, Alexandra Fedorovna now took responsibility for domestic policy. Rasputin served as her adviser and over the next few months she dismissed ministers and their deputies in rapid succession. In letters to her husband she called his ministers as "fools and idiots". According to David Shub "the real ruler of Russia was the Empress Alexandra". (20)

On 7th July, 1915, the Tsar wrote to his wife and complained about the problems he faced fighting the war: "Again that cursed question of shortage of artillery and rifle ammunition - it stands in the way of an energetic advance. If we should have three days of serious fighting we might run out of ammunition altogether. Without new rifles it is impossible to fill up the gaps.... If we had a rest from fighting for about a month our condition would greatly improve. It is understood, of course, that what I say is strictly for you only. Please do not say a word to anyone." (21)

In 1916 two million Russian soldiers were killed or seriously wounded and a third of a million were taken prisoner. Millions of peasants were conscripted into the Tsar's armies but supplies of rifles and ammunition remained inadequate. It is estimated that one third of Russia's able-bodied men were serving in the army. The peasants were therefore unable to work on the farms producing the usual amount of food. By November, 1916, food prices were four times as high as before the war. As a result strikes for higher wages became common in Russia's cities. (22)

The Assassination of Rasputin

Rumours began to circulate that Rasputin and Alexandra Fedorovna were leaders of a pro-German court group and were seeking a separate peace with the Central Powers. This upset Michael Rodzianko, the President of the Duma, and he told Nicholas II: "I must tell Your Majesty that this cannot continue much longer. No one opens your eyes to the true role which this man (Rasputin) is playing. His presence in Your Majesty's Court undermines confidence in the Supreme Power and may have an evil effect on the fate of the dynasty and turn the hearts of the people from their Emperor." (23)

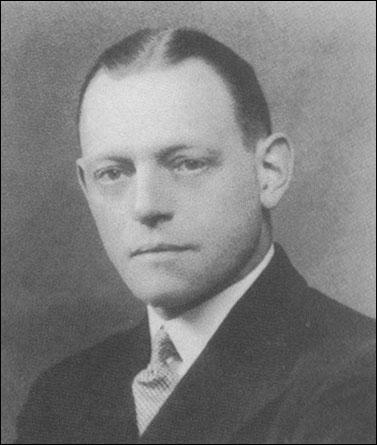

Mansfield Smith-Cumming, the head of MI6, became very concerned by the influence Rasputin was having on Russia's foreign policy. Samuel Hoare was assigned to the British intelligence mission with the Russian general staff. Soon afterwards he was given the rank of lieutenant-colonel and Mansfield Smith-Cumming appointed him as head of the British Secret Intelligence Service in Petrograd. Other members of the unit included Oswald Rayner, Cudbert Thornhill, John Scale and Stephen Alley. One of their main tasks was to deal with Rasputin who was considered to be "one of the most potent of the baleful Germanophil forces in Russia." (24)

The main fear was that Russia might negotiate a separate peace with Germany, thereby releasing the seventy German divisions tied down on the Eastern Front. One MI6 agent wrote: "German intrigue was becoming more intense daily. Enemy agents were busy whispering of peace and hinting how to get it by creating disorder, rioting, etc. Things looked very black. Romania was collapsing, and Russia herself seemed weakening. The failure in communications, the shortness of foods, the sinister influence which seemed to be clogging the war machine, Rasputin the drunken debaucher influencing Russia's policy, what was to the be the end of it all?" (25)

Samuel Hoare reported in December 1916 that poor leadership and inadequate weaponry had led to Russian war fatigue: "I am confident that Russia will never fight through another winter." In another dispatch to headquarters Hoare suggested that if the Tsar banished Rasputin "the country would be freed from the sinister influence that was striking down to natural leaders and endangering the success of its armies in the field." Giles Milton, the author of Russian Roulette: How British Spies Thwarted Lenin's Global Plot (2013) argues that it was at this point that MI6 made plans to assassinate Rasputin. (26)

At the same time Vladimir Purishkevich, the leader of the monarchists in the Duma, was also attempted to organize the elimination of Rasputin. He wrote to Prince Felix Yusupov: "I'm terribly busy working on a plan to eliminate Rasputin. That is simply essential now, since otherwise everything will be finished... You too must take part in it. Dmitri Pavlovich Romanov knows all about it and is helping. It will take place in the middle of December, when Dmitri comes back... Not a word to anyone about what I've written." (27)

Yusupov replied the following day: "Many thanks for your mad letter. I could not understand half of it, but I can see that you are preparing for some wild action.... My chief objection is that you have decided upon everything without consulting me... I can see by your letter that you are wildly enthusiastic, and ready to climb up walls... Don't you dare do anything without me, or I shall not come at all!" (28)

Eventually, Vladimir Purishkevich and Felix Yusupov agreed to work together to kill Rasputin. Three other men Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich Romanov, Dr. Stanislaus de Lazovert and Lieutenant Sergei Mikhailovich Sukhotin, an officer in the Preobrazhensky Regiment, joined the plot. Lazovert was responsible for providing the cyanide for the wine and the cakes. He was also asked to arrange for the disposal of the body. (29)

Yusupov later admitted in Lost Splendor (1953) that on 29th December, 1916, Rasputin was invited to his home: "The bell rang, announcing the arrival of Dmitri Pavlovich Romanov and my other friends. I showed them into the dining room and they stood for a little while, silently examining the spot where Rasputin was to meet his end. I took from the ebony cabinet a box containing the poison and laid it on the table. Dr Lazovert put on rubber gloves and ground the cyanide of potassium crystals to powder. Then, lifting the top of each cake, he sprinkled the inside with a dose of poison, which, according to him, was sufficient to kill several men instantly. There was an impressive silence. We all followed the doctor's movements with emotion. There remained the glasses into which cyanide was to be poured. It was decided to do this at the last moment so that the poison should not evaporate and lose its potency." (30)

Vladimir Purishkevich supported this story in his book, The Murder of Rasputin (1918): "We sat down at the round tea table and Yusupov invited us to drink a glass of tea and to try the cakes before they had been doctored. The quarter of an hour which we spent at the table seemed like an eternity to me.... Yusupov gave Dr Lazovert several pieces of the potassium cyanide and he put on the gloves which Yusupov had procured and began to grate poison into a plate with a knife. Then picking out all the cakes with pink cream (there were only two varieties, pink and chocolate), he lifted off the top halves and put a good quantity of poison in each one, and then replaced the tops to make them look right. When the pink cakes were ready, we placed them on the plates with the brown chocolate ones. Then, we cut up two of the pink ones and, making them look as if they had been bitten into, we put these on different plates around the table." (31)

Lazovert now went out to collect Rasputin in his car on the evening of 29th December, 1916. While the other four men waited at the home of Yusupov. According to Lazovert: "At midnight the associates of the Prince concealed themselves while I entered the car and drove to the home of the monk. He admitted me in person. Rasputin was in a gay mood. We drove rapidly to the home of the Prince and descended to the library, lighted only by a blazing log in the huge chimney-place. A small table was spread with cakes and rare wines - three kinds of the wine were poisoned and so were the cakes. The monk threw himself into a chair, his humour expanding with the warmth of the room. He told of his successes, his plots, of the imminent success of the German arms and that the Kaiser would soon be seen in Petrograd. At a proper moment he was offered the wine and the cakes. He drank the wine and devoured the cakes. Hours slipped by, but there was no sign that the poison had taken effect. The monk was even merrier than before. We were seized with an insane dread that this man was inviolable, that he was superhuman, that he couldn't be killed. It was a frightful sensation. He glared at us with his black, black eyes as though he read our minds and would fool us." (32)

Vladimir Purishkevich later recalled that Felix Yusupov joined them upstairs and exclaimed: "It is impossible. Just imagine, he drank two glasses filled with poison, ate several pink cakes and, as you can see, nothing has happened, absolutely nothing, and that was at least fifteen minutes ago! I cannot think what we can do... He is now sitting gloomily on the divan and the only effect that I can see of the poison is that he is constantly belching and that he dribbles a bit. Gentlemen, what do you advise that I do?" Eventually it was decided that Yusupov should go down and shoot Rasputin. (33)

Yusupov later recalled : "I looked at my victim with dread, as he stood before me, quiet and trusting.... Rasputin stood before me motionless, his head bent and his eyes on the crucifix. I slowly raised the crucifix. I slowly raised the revolver. Where should I aim, at the temple or at the heart? A shudder swept over me; my arm grew rigid, I aimed at his heart and pulled the trigger. Rasputin gave a wild scream and crumpled up on the bearskin. For a moment I was appalled to discover how easy it was to kill a man. A flick of a finger and what had been a living, breathing man only a second before, now lay on the floor like a broken doll." (34)

Stanislaus de Lazovert agrees with this account except that he was uncertain who fired the shot: "With a frightful scream Rasputin whirled and fell, face down, on the floor. The others came bounding over to him and stood over his prostrate, writhing body. We left the room to let him die alone, and to plan for his removal and obliteration. Suddenly we heard a strange and unearthly sound behind the huge door that led into the library. The door was slowly pushed open, and there was Rasputin on his hands and knees, the bloody froth gushing from his mouth, his terrible eyes bulging from their sockets. With an amazing strength he sprang toward the door that led into the gardens, wrenched it open and passed out." Lazovert added that it was Vladimir Purishkevich who fired the next shot: "As he seemed to be disappearing in the darkness, Purishkevich, who had been standing by, reached over and picked up an American-made automatic revolver and fired two shots swiftly into his retreating figure. We heard him fall with a groan, and later when we approached the body he was very still and cold and - dead." (35)

Felix Yusupov added: "Rasputin lay on his back. His features twitched in nervous spasms; his hands were clenched, his eyes closed. A bloodstain was spreading on his silk blouse. A few minutes later all movement ceased. We bent over his body to examine it. The doctor declared that the bullet had struck him in the region of the heart. There was no possibility of doubt: Rasputin was dead. We turned off the light and went up to my room, after locking the basement door." (36)

The Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich Romanov drove the men to Varshavsky Rail Terminal where they burned Rasputin's clothes. "It was very late and the grand duke evidently feared that great speed would attract the suspicion of the police." They also collected weights and chains and returned to Yusupov's home. At 4.50 a.m. Romanov drove the men and Rasputin's body to Petrovskii Bridge. that crossed towards Krestovsky Island. According to Vladimir Purishkevich: "We dragged Rasputin's corpse into the grand duke's car." Purishkevich claimed he drove very slowly: "It was very late and the grand duke evidently feared that great speed would attract the suspicion of the police." (37) Stanislaus de Lazovert takes up the story when they arrived at Petrovskii: "We bundled him up in a sheet and carried him to the river's edge. Ice had formed, but we broke it and threw him in. The next day search was made for Rasputin, but no trace was found." (38)

The following day the Tsarina wrote to her husband about the disappearance of Rasputin: "We are sitting here together - can you imagine our feelings - our friend has disappeared. Felix Yusupov pretends he never came to the house and never asked him." (39) The next day she wrote: "No trace yet... the police are continuing the search... I fear that these two wretched boys (Felix Yusupov and Dmitri Romanov) have committed a frightful crime but have not yet lost all hope." (40)

Rasputin's body was found on 19th December by a river policeman who was walking on the ice. He noticed a fur coat trapped beneath, approximately 65 metres from the bridge. The ice was cut open and Rasputin's frozen body discovered. The post mortem was held the following day. Major-General Popel carried out the investigation of the murder. By this time Dr. Stanislaus de Lazovert and Lieutenant Sergei Mikhailovich Sukhotin had fled from the city. He did interview Felix Yusupov, Dmitri Pavlovich Romanov and Vladimir Purishkevich, but he decided not to charge them with murder. (41)

Tsar Nicholas II ordered the three men to be expelled from Petrograd. He rejected a petition to allow the conspirators to stay in the city. He replied that "no one had the right to commit murder." Sophie Buxhoeveden later commented: "Though patriotic feeling was supposed to have been the motive of the murder, it was the first indirect blow at the Emperor's authority, the first spark of insurrection. In short, it was the application of lynch law, the taking of law and judgment forcibly into private hands." (42)

Several historians have questioned the official account of the death of Rasputin. They claim that the post mortem of Rasputin carried out by Professor Dmitrii Kosorotov, does not support the evidence provided by the confessions of Felix Yusupov, Dr. Stanislaus de Lazovert and Vladimir Purishkevich. For example, the "examination reveals no trace of poison". It also appears that Rasputin suffered a violent beating: "the victim's face and body carry traces of blows given by a supple but hard object. His genitals have been crushed by the action of a similar object." (43)

Kosorotov also claims that Rasputin was shot by men using three different guns. One of these was a Webley revolver, a gun issued to British intelligence agents. Michael Smith, the author of Six: A History of Britain's Secret Intelligence Service (2010), argues that Oswald Rayner took part in the assassination: "He (Rasputin) was shot several times, with three different weapons, with all the evidence suggesting that Rayner fired the fatal shot, using his personal Webley revolver." (44)

Primary Sources

(1) Michael Rodzianko, the President of the Duma, later wrote about the role of Rasputin during the First World War in his book, The Fall of the Empire (1973).

Profiting by the Tsar's arrival at Tsarskoe I asked for an audience and was received by him on March 8th. "I must tell Your Majesty that this cannot continue much longer. No one opens your eyes to the true role which this man (Rasputin) is playing. His presence in Your Majesty's Court undermines confidence in the Supreme Power and may have an evil effect on the fate of the dynasty and turn the hearts of the people from their Emperor". My report did some good. On March 11th an order was issued sending Rasputin to Tobolsk; but a few days later, at the demand of the Empress, the order was cancelled.

(2) Ariadna Tyrkova, From Liberty to Brest-Litovsk (1918)

The Duma gradually became the authoritative centre of patriotic and therefore opposition elements. It was an opposition rallied around the motto, “Defence of the Fatherland.” The mere shadow of an agreement with Germany provoked the sharp protest of these circles. For the purpose of a more energetic carrying-on of the war the people’s representatives persistently demanded “a Ministry of confidence,” i.e. that the blind, unpopular, incapable, and unintelligent Ministers should be replaced by universally respected, honourable public men. Nicholas II. remained deaf to these demands, treating them as an insolent infringement of his prerogative as an autocrat. His tenacity augmented the opposition. Throughout Russia, both at the front and at home, rumour grew ever louder concerning the pernicious influence exercised by the Empress Alexandra Feodorovna, at whose side rose the sinister figure of Gregory Rasputin. This charlatan and hypnotist had wormed himself into the Tsar’s palace and gradually acquired a limitless power over the hysterical Empress, and through her over the Sovereign. Rasputin’s proximity to the Tsar’s family proved fatal to the dynasty, for no political criticism can harm the prestige of Tsars so effectually as the personal weakness, vice, or debasement of the members of a royal house.

Rumours were current, up to now unrepudiated, but likewise unconfirmed, that the Germans were influencing Alexandra Feodorovna through the medium of Rasputin and Stürmer. Haughty and unapproachable, she lacked popularity, and was all the more readily suspected of almost anything, even of pro-Germanism, since the crowd is always ready to believe anything that tends to augment their suspicions. In November the Duma made an emphatic demand for a change in the Government’s policy. On the 14th of November the leader of the opposition, P.N. Milyukov, made a historical speech, which is considered by many as marking the first day of the revolution. Characterising the policy of the Prime Minister, Stürmer, P.N. Milyukov pointed out that in dwelling upon the conduct of the head of the Government one could not refrain from putting the question, “ What is it, folly or treason ? ”

In those days these words were upon everybody’s lips. The incapacity of the authorities became ever more apparent. Government circles were incapable of realising the necessity of granting concessions. Meanwhile only in unison with trusted statesmen could the Government bring the war with Germany to a victorious end.

The assassination of Rasputin came as a first consequence of the speeches uttered in the Duma. This was a society revolt, a protest of aristocrats and monarchists against the degradation of the Tsar’s dignity. The circles which planned this assassination had not the habit of political reflection. They did not realise that Rasputin was not a casual phenomenon, but the sign of the profound dissolution of the autocratic principle, which the monarchists aspired to save. The leading part in Rasputin’s murder was played by the young Count Yusupov-Sumarokov-Elston, one of the wealthiest of Russian aristocrats, a relative of the Tsar by his marriage with the daughter of Nicholas II’s sister.

His chief assistant and accomplice was one of the most gifted and energetic defenders of the autocracy, a member of the Duma, Vl. Purishkevich. By exterminating the evil genius of the Tsar’s family these men hoped to purify the principle of autocracy itself and save the old regime. But nothing was changed with Rasputin’s removal, nothing improved either in affairs of the State or in the Tsar’s situation. Formerly the Tsar’s various mistakes and weaknesses were attributed to Rasputin’s evil influence - now the last veil had been withdrawn and the insignificant little officer, slightly educated, unintelligent, incapable of following and grasping all the complexity of contemporary social and political life - stood out, a lonely figure attracting the ever more malevolent attention of public opinion. Rasputin was no more, but the Ministers appointed by this half-illiterate rascal remained at their posts and conducted the affairs of the State as if still guided by his shadow.

(3) Alexander Kerensky, Russia and History's Turning Point (1965)

The Tsarina's blind faith in Rasputin led her to seek his counsel not only in personal matters but also on questions of state policy. General Alekseyev, held in high esteem by Nicholas II, tried to talk to the Tsarina about Rasputin, but only succeeded in making an implacable enemy of her. General Alexseyev told me later about his profound concern on learning that a secret map of military operations had found its way into the Tsarina's hands. But like many others, he was powerless to take any action.

On January 19, Goremykin was replaced by Sturmer, an extreme reactionary who hated the very idea of any form of popular representation or local self-government. Even more important, he was undoubtedly a believer in the need for an immediate cessation of the war with Germany.

During his first few months in office, Sturmer was also Minister of Interior, but the post of Minister of Foreign Affairs was still held by Sazonov, who firmly advocated honouring the alliance with Britain and France and carrying on the war to the bitter end, and who recognized the Cabinet's obligation to pursue a policy in tune with the sentiments of the majority in the Duma.

On August 9, however, Sazonov was suddenly dismissed. His portfolio was taken over by Sturmer, and on September 16, Protopopov was appointed acting Minister of the Interior. The official government of the Russian Empire was now entirely in the hands of the Tsarina and her advisers.

(4) Bernard Pares, a British academic, met Gregory Rasputin several times before his death in 1916.

Count Witte never swerved from his conviction, firstly, that Russia must avoid the war at all costs, and secondly, that she must work for economic friendship with France and Germany to counteract the preponderance of England. Nicholas detested him, and now more than ever; but on March 13th Witte died suddenly.

The other formidable opponent still remained. Rasputin was opposed to the war for reasons as good as Witte's. He was for peace between all nations and between all religions. He claimed to have averted was both in 1909 and in 1912, and his claim was believed by others.

(5) Gregory Rasputin, in conversation with Felix Yusupov (29th December, 1916)

The aristocrats can't get used to the idea that a humble peasant should be welcome at the Imperial Palace. They are consumed with envy and fury. But I'm not afraid of them. They can't do anything to me. I'm protected against ill fortune. There have been several attempts on my life but the Lord has always frustrated these plots. Disaster will come to anyone who lifts a finger against me.

(6) Felix Yusupov, Lost Splendor (1953)

I looked at my victim with dread, as he stood before me, quiet and trusting. What had become of his second-sight? What good did his gift of foretelling the future do him? Of what use was his faculty for reading the thoughts of others, if he was blind to the dreadful trap that was laid for him? It seemed as though fate had clouded his mind. But suddenly, in a lightening flash of memory, I seemed to recall every stage of Rasputin's infamous life. My qualms of conscience disappeared, making room for a firm determination to complete my task.

"Grigory Yefimovich," I said, "you'd better look at the crucifix and say a prayer." Rasputin cast a surprised, almost frightened glance at me. I read in it an expression which I had never known him to have: it was at once gentle and submissive. He came quite close to me and looked me full in the face.

I realized that the hour had come. "O Lord," I prayed, "give me the strength to finish it." Rasputin stood before me motionless, his head bent and his eyes on the crucifix. I slowly raised the crucifix. I slowly raised the revolver. Where should I aim, at the temple or at the heart? A shudder swept over me; my arm grew rigid, I aimed at his heart and pulled the trigger. Rasputin gave a wild scream and crumpled up on the bearskin. For a moment I was appalled to discover how easy it was to kill a man. A flick of a finger and what had been a living, breathing man only a second before, now lay on the floor like a broken doll.

On hearing the shot my friends rushed in. Rasputin lay on his back. His features twitched in nervous spasms; his hands were clenched, his eyes closed. A bloodstain was spreading on his silk blouse. A few minutes later all movement ceased. We bent over his body to examine it. The doctor declared that the bullet had struck him in the region of the heart. There was no possibility of doubt: Rasputin was dead. We turned off the light and went up to my room, after locking the basement door.

Our hearts were full of hope, for we were convinced that what had just taken place would save Russia and the dynasty from ruin and dishonour. As we talked I was suddenly filled with a vague misgiving; an irresistible impulse forced me to go down to the basement.

Rasputin lay exactly where we had left him. I felt his pulse: not a beat, he was dead. All of a sudden, I saw the left eye open. A few seconds later his right eyelid began to quiver, then opened. I then saw both eyes - the green eyes of a viper - staring at me with an expression of diabolical hatred. The blood ran cold in my veins. My muscles turned to stone.

Then a terrible thing happened: with a sudden violent effort Rasputin leapt to his feet, foaming at the mouth. A wild roar echoed through the vaulted rooms, and his hands convulsively thrashed the air. He rushed at me, trying to get at my throat, and sank his fingers into my shoulder like steel claws. His eyes were bursting from their sockets. By a superhuman effort I succeeded in freeing myself from his grasp.

"Quick, quick, come down!" I cried, "He's still alive." He was crawling on hands and knees, grasping and roaring like a wounded animal. He gave a desperate leap and managed to reach the secret door which led into the courtyard. Knowing that the door was locked, I waited on the landing above grasping my rubber club. To my horror I saw the door open and Rasputin disappear. Purishkevich sprang after him. Two shots echoed through the night. I heard a third shot, then a fourth. I saw Rasputin totter and fall beside a heap of snow.

(7) Stanislaus de Lazovert, testimony (undated)

The shot that ended the career of the blackest devil in Russian history was fired by my close and beloved friend, Vladimir Purishkevich, Reactionary Deputy of the Duma.

Five of us had been arranging for this event for many months. On the night of the killing, after all details had been arranged, I drove to the Imperial Palace in an automobile and persuaded this black devil to accompany me to the home of Prince Yusupov, in Petrograd.

Later that night M. Purishkevich followed him into the gardens adjoining Yusupov's house and shot him to death with an automatic revolver. We then carried his riddled body in a sheet to the River Neva, broke the ice and cast him in.

The story of Rasputin and his clique is well known. They sent the army to the trenches without food or arms, they left them there to be slaughtered, they betrayed Rumania and deceived the Allies, they almost succeeded in delivering Russia bodily to the Germans.

Rasputin, as a secret member of the Austrian Green Hand, had absolute power in Court. The Tsar was a nonentity, a kind of Hamlet, his only desire being to abdicate and escape the whole vile business.

Rasputin continued his life of vice, carousing and passion. The Grand Duchess reported these things to the Tsarina and was banished from Court for her pains.

This was the condition of affairs when we decided to kill this monster. Only five men participated in it. They were the Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich, Prince Yusupov, Vladimir Purishkevich, Captain Sukhotin and myself.

Prince Yusupov's palace is a magnificent place on the Nevska. The great hall has six equal sides and in each hall is a heavy oaken door. One leads out into the gardens, the one opposite leads down a broad flight of marble stairs to the huge dining room, one to the library, etc.

At midnight the associates of the Prince concealed themselves while I entered the car and drove to the home of the monk. He admitted me in person.

Rasputin was in a gay mood. We drove rapidly to the home of the Prince and descended to the library, lighted only by a blazing log in the huge chimney-place. A small table was spread with cakes and rare wines - three kinds of the wine were poisoned and so were the cakes.

The monk threw himself into a chair, his humour expanding with the warmth of the room. He told of his successes, his plots, of the imminent success of the German arms and that the Kaiser would soon be seen in Petrograd.

At a proper moment he was offered the wine and the cakes. He drank the wine and devoured the cakes. Hours slipped by, but there was no sign that the poison had taken effect. The monk was even merrier than before.

We were seized with an insane dread that this man was inviolable, that he was superhuman, that he couldn't be killed. It was a frightful sensation. He glared at us with his black, black eyes as though he read our minds and would fool us.

And then after a time he rose and walked to the door. We were afraid that our work had been in vain. Suddenly, as he turned at the door, some one shot at him quickly.

With a frightful scream Rasputin whirled and fell, face down, on the floor. The others came bounding over to him and stood over his prostrate, writhing body.

It was suggested that two more shots be fired to make certain of his death, but one of those present said, "No, no; it is his last agony now."

We left the room to let him die alone, and to plan for his removal and obliteration.

Suddenly we heard a strange and unearthly sound behind the huge door that led into the library. The door was slowly pushed open, and there was Rasputin on his hands and knees, the bloody froth gushing from his mouth, his terrible eyes bulging from their sockets. With an amazing strength he sprang toward the door that led into the gardens, wrenched it open and passed out.

As he seemed to be disappearing in the darkness, F. Purishkevich, who had been standing by, reached over and picked up an American-made automatic revolver and fired two shots swiftly into his retreating figure. We heard him fall with a groan, and later when we approached the body he was very still and cold and - dead.

We bundled him up in a sheet and carried him to the river's edge. Ice had formed, but we broke it and threw him in. The next day search was made for Rasputin, but no trace was found.

Urged on by the Tsarina, the police made frantic efforts, and finally a rubber was found which was identified as his. The river was dragged and the body recovered.

I escaped from the country. Purishkevich also escaped. But Prince Yusupov was arrested and confined to the boundaries of his estate. He was later released because of the popular approval of our act.

Russia had been freed from the vilest tyrant in her history; and that is all.

(8) Vladimir Mitrofanovich Purishkevich, The Murder of Rasputin (1918)

These were my recollections as I sat in the rear of the car, with the lifeless corpse of the "venerable old man", which we were taking to its eternal resting place, lying at my feet. I looked out of the window. To judge by the surrounding houses and the endless fences, we had already left the city. There were very few lights. The road deteriorated and we hit bumps and holes which made the body lying at our feet bounce around (despite the soldier sitting on it). I felt a nervous tremor run through me at each bump as my knees touched the repulsive, soft corpse which, despite the cold, had not yet completely stiffened. At last the bridge from which we were to fling Rasputin's body into the hole in the ice appeared in the distance. Demitrii Pavlovich slowed down, drove onto the left side of the bridge and stopped by the guard rail....

I opened the car doors quietly and, as quickly as possible, jumped out and went over to the railing. The soldier and Dr Lazovert followed me and then Lieutenant S., who had been sitting by the grand duke, joined us and together we swung Rasputin's corpse and flung it forcefully into the ice hole just by the bridge. (Dmitrii Pavlovich stood guard in front of the car.) Since we had forgotten to fasten the weights on the corpse with a chain, we hastily threw these, one after another, after it. Likewise, we stuffed the chains into the dead man's coat and threw it into the same hole. Next, Dr Lazovert searched in the dark car and found one of Rasputin's boots, which he also flung off the bridge. All of this took no more than two or three minutes. Then Dr Lazovert, Lieutenant S. and the soldier got into the back of the car, and I got in next to Dmitrii Pavlovich. We turned on the headlights again and crossed the bridge.

How we failed to be noticed on the bridge is still amazing to me to this day. For, as we passed the sentry-box, we noticed a guard next to it. But he was sleeping so deeply that he had apparently not woken up even when... we had inadvertently not only lit up his sentry-box, but had even turned the lights on him.

(9) Professor Dmitrii Kosorotov, post mortem of Grigory Rasputin (20th December 1916)

The body is that of a man of about fifty years old, of medium size, dressed in a blue embroidered hospital robe, which covers a white shirt. His legs, in tall animal skin boots, are tied with a rope, and the same rope ties his wrists. His dishevelled hair is light brown, as are his long moustache and beard, and it's soaked with blood. His mouth is half open, his teeth clenched. His face below his forehead is covered in blood. His shirt too is also marked with blood. There are three bullet wounds. The first has penetrated the left side of the chest and has gone through the stomach and the liver...

Examination of the head: the cerebral matter gave off a strong smell of alcohol. Examination of the stomach: the stomach contains about twenty soup spoons of liquid smelling of alcohol. The examination reveals no trace of poison. Wounds: his left side has a weeping wound, due to sonic sort of slicing object or a sword. His right eye has come out of its cavity and falls down onto his face. At the corner of the right eye the membrane is torn. His right ear is hanging down and torn. His neck has a wound from some sort of' rope tie. The victim's face and body carry traces of blows given by a supple but hard object. His genitals have been crushed by the action of a similar object...

Haemorrhage caused by the wound to the liver and the wound to the right kidney must have started the rapid decline of his strength. In this case, he would have died in ten or twenty minutes. At the moment of death the deceased was in a state of drunkenness. The first bullet passed through the stomach and the liver. This mortal blow had been shot from a distance of 20 centimetres. The wound on the right side, made at nearly exactly the same time as the first, was also mortal; it passed through the right kidney. The victim, at the time of the murder, was standing. When he was shot in the forehead, his body was already on the ground.

(10) General Globachyov, the head of Okhrana, report on the murder of Grigory Rasputin (December, 1916)

On the night from the sixteenth to the seventeenth the point duty policeman heard several shots near 94 Moika, owned by Prince Yusupov. Soon after that the policeman was invited to the study of the young Prince Yusupov, where the prince and a stranger who called himself Purishkevich were present. The latter said: "I am, Purishkevich. Rasputin has perished. If you love the Tsar and fatherland you will keep silent." The policeman reported this to his superiors. The investigation conducted this morning established that one of Yusupov's guests had fired a shot in the small garden adjacent to No. 94 at around 3 a.m. The garden has a direct entrance to the prince's study. A human scream was heard and following that a sound of a car being driven away. The person who had fired the shot was wearing a military field uniform.

Traces of blood have been found on the snow in the small garden in the course of close examination. When questioned by the governor of the city, the young prince stated that he had had a party that night, but that Rasputin was not there, and that Grand Duke Dmitrii Pavlovich had shot a watchdog. The dog's body was found buried in the snow. The investigation conducted at Rasputin's residence at 64 Gorokhovava Street established that at 10 p.m. on 16 December Rasputin said that he was not going to go out any more that night and was going to sleep. He let off his security and the car in his normal fashion. Questioning the servants and the yard keeper allowed police to establish that at 12:30 a.m, a large canvas-top car with driver and a stranger in it arrived at the house. The stranger entered Rasputin's apartment through the back door. It seemed that Rasputin was expecting him because he greeted him as somebody he knew and soon went outside with him through the same entrance. Rasputin got into the car, which drove of along Gorokhovava Street towards Morskava Street. Rasputin has not returned home and has not been found despite the deployed measures.

(11) General Peter Wrangel was on the Eastern Front when he heard of Rasputin's death. He wrote about this incident in his Memoirs (1929)

During the march an orderly came to inform me that General Krymov, who was marching at the head of our column, wanted me. I found him with our General Staff busily reading a letter which had just come. Whilst I was still some way off he called out to me: "Great news! At last they have killed that scoundrel Rasputin.!"

The newspapers announced the bare facts, letters from the capital gave the details. Of the three assassins, I knew two intimately. What had been their motive? Why, having killed a man whom they regarded as a menace to the country, had they not admitted their action before everyone? Why had they not admitted their action before everyone? Why had they not relied on justice and public opinion instead of trying to hide all trace of the murder by burying the body under the ice? we thought over the news with great anxiety.

(12) Richard Norton-Taylor, The Guardian (22nd September, 2010)

Jeffery said he found no evidence to support recent claims that MI6 was involved in the assassination in 1916 of Rasputin, the notorious "mad monk" who had insinuated himself into the Russian royal family. "All I can tell is what I found in the archives … If MI6 had a part in the killing of Rasputin, I would have expected to have found some trace of that," Jeffery said. The book does, however, refer to a colourful account of the murder by MI6's man in Moscow, Sir Samuel Hoare – a future government minister – who said he was "writing in the style of the Daily Mail" because it was "so sensational that one cannot describe it as one would if it were an ordinary episode of the war".

Hoare wrote: "True to his nickname ('the rake') it was at an orgy that Rasputin met his death." Jeffery notes simply that Rasputin "was murdered in the early hours of the morning of Saturday 30 December". In his recently published book Six, the author and journalist Michael Smith refers to a number of claims that Rasputin was shot several times with three different weapons "with all the evidence suggesting that [MI6 officer Oswald] Rayner fired the fatal shot, using his personal Webley revolver".

(13) Richard Cullen, Rasputin: The Role of Britain's Secret Service in his Torture and Murder (2010)

Questions have also been raised about why Alley should write such a letter and how it would reach Scale. The days of mobile phones were many decades away, of course, and communication was generally either by telegram or letter so a letter is a reasonable way to communicate, sent either by courier or by normal military dispatches.

In the absence of evidence to the contrary the letter has to be accepted as genuine or else - and the spectre of this concerns me created ex post facto for the purpose of financial gain, a view which I do not accept and in the absence of proof reject. I have seen criticism of the content of the letter that suggests it does not conclusively show British involvement, the logic of which eludes me. Let me dissect it.

"Dear Scale, No response has thus far been received from London in respect of your oilfields proposal.' There is clear evidence to show Scale's involvement in the destruction of the Romanian oil fields in face of the advancing German troops.

"Although matters have not proceeded entirely to plan, our objective has clearly been achieved." Well, we know things had not gone to plan: the body had been recovered from the Nevka when the intention was that it would never he seen again; Yusupov had been detained at the station on the way to the Crimea, the police had attended the Yusupov Palace as a result of hearing "shots". But if the objective was, as I suggest, to prevent a separate peace with Germany by removing Rasputin, then yes, it had been achieved.

"Reaction to the demise of Dark Forces has been well received by all, although a few awkward questions have already been asked about wider involvement." We know that Purishkevich referred to Rasputin as Dark Forces, and we know from the Scale papers and from his daughter's evidence that her father used the same term when referring to Rasputin - this was the accepted code word for him. This issue is not in doubt and William Queux used the term Dark Forces to describe Rasputin as early as 1918. Brian Moynahan provides more information about how commonly the term was applied to Rasputin when he tells us:

On December 8 the Union of Towns, an important municipal body, went into secret session. It passed a resolution: "The government, now become an instrument of the dark forces, is driving Russia to her ruin and is shattering the imperial throne. In this grave hour the country requires a government worthy of a great people. There is not a clay to lose!' Secrets were no longer kept. The resolution was circulated in Roneo script in thousands of copies. Dark forces was simple code for Grigorii Rasputin and those about him.

And I hope no one would doubt he died and therefore it was his "demise". We know that awkward questions had been asked: the Tsar confronted the British ambassador and accused Rayner (although not by name) of being involved. Hoare had become involved in the debate and there were some very tricky questions to be answered.

Alley's letter goes on: "Rayner is attending to loose ends and will no doubt brief you on your return." We know that Rayner was with Yusupov the morning after the murder, and we also know he was with Yusupov at the station when Yusupov was arrested.

It is very difficult to see how anyone, given the analysis of the letter and the facts I have outlined above, cannot say that it provides primary evidence of British involvement and that the "accepted version" of the events was in fact a cynical conspiracy to pervert the course of justice.

(14) Michael Smith, Six: A History of Britain's Secret Intelligence Service (2010)

The key link between the British secret service bureau in Petrograd and the Russians plotting Rasputin's demise was Rayner through his relationship with Prince Yusupov, the leader of the Russian plotters. Yusupov enticed Rasputin to his family's palace on the banks of the river Neva in Petrograd for a "party", with the prospect of sex apparently high on the agenda. Yusupov told his wife Princess Irina, the Tsar's niece, that she was to be used as "the lure" to entice Rasputin to attend the party, a suggestion that appears to have persuaded her to extend a holiday in the Crimea so she was not in Petrograd at the time. Those known to have been present for the "party" in the Yusupov palace, apart from Rasputin, include Yusupov himself; the Grand Duke Dmitry Pavlovich, the Tsar's second cousin; Purishkevich; Lieutenant Sergei Sukhotin, a friend of Yusupov's; Dr Stanislaus de Lazovert, the medical officer of Purishkevich's military unit, who was recruited as the driver; plus Rayner.

Once there Rasputin was plied with drink and then tortured in order to discover the truth of his alleged links with a German attempt to persuade Russia to leave the war. The torture was carried out with an astonishing level of violence, probably using a heavy rubber cosh - the original autopsy report found that his testicles had been "crushed" flat and there is more than a suspicion that the extent of the damage was fuelled by sexual jealousy. Yusupov, who is believed to have had a homosexual relationship with another of the plotters, the Grand Duke Dimitri, is also alleged to have had a previous sexual liaison with Rasputin. Whatever Rasputin actually told the conspirators, and someone in his predicament could be expected to say anything that might end the ordeal, they had no choice then but to murder him and dispose of the body. He was shot several tunes, with three different weapons, with all the evidence suggesting that Rayner fired the final fatal shot, using his personal Webley revolver. Rasputin's body was then dumped through an ice hole in the Neva.

(15) Giles Milton, Russian Roulette: How British Spies Thwarted Lenin's Global Plot (2013)

Yusupov's account details not only his own role in the murder, but also that of Grand Duke Dmitri, Vladimir Purishkevich and Dr Lazovert, as well as Captain Sergei Soukhatin. However, in the days that followed, there were rumours of a sixth conspirator in the palace. Someone else was said to have been present that night - a professional assassin who was working in the shadows.

What Yusupov was at pains to conceal was that Oswald Rayner, a key member of the Russian bureau's secret inner circle, had also been there that night. His critical role in the killing might have remained a secret for all time had it not been for a fatal mistake on the part of the murderers.

The mistake occurred in the aftermath of the murder, when the plotters were disposing of the body. Yusupov and his friends had assumed that the corpse would sink beneath the ice and be flushed out into the Gulf of Finland. There, trapped under the ice for the rest of the winter, it would be lost forever. What they had never expected was that Rasputin's corpse would be found and plucked from the icy waters.

Rasputin's corpse was spotted in the Neva River on the second full day after his death. A river policeman noticed a fur coat lodged beneath the ice and ordered the frozen crust to be broken. The body was carefully prised from its icy sepulchre and taken to the mortuary room of Chesmenskii Hospice. Here, an autopsy was undertaken by Professor Dmitrii Kosorotov.

The professor noted that the corpse was in a terrible state of mutilation: "his left side has a weeping wound, due to some sort of slicing object or a sword. His right eye has come out of its cavity and falls down onto his face... His right ear is hanging down and torn. His neck has a wound from some sort of rope tie. The victim's face and body carry traces of blows given by a supple but hard object: These injuries suggest that Rasputin had been garrotted and repeatedly beaten with a heavy cosh.

Even more horrifying was the damage to his genitals. At some point during the brutal torture, his legs had been wrenched apart and his testicles had been "crushed by the action of a similar object." In fact, they had been flattened and completely destroyed.

Other details gleaned by Professor Kosorotov suggest that Yusupov's melodramatic account of the murder was nothing more than fantasy. Yet it was fantasy with a purpose. It was imperative for Yusupov to depict Rasputin as a demonic, superhuman figure whose malign hold over the tsarina was proving disastrous for Russia. The only way he could escape punishment for the murder was to present himself as the saviour of Russia: the man who had rid the country of an evil force.

The story of the poisoned cakes was almost certainly an invention: the postmortem included an examination of the contents of Rasputin's stomach: "The examination," wrote the professor, "reveals no trace of poison."

Professor Kosorotov also examined the three bullet wounds in Rasputin's body. "The first has penetrated the left side of the chest and has gone through the stomach and liver," he wrote. "The second has entered into the right side of the back and gone through the kidney." Both of these would have inflicted terrible wounds. But the third bullet was the fatal shot. "It hit the victim on the forehead and penetrated into his brain."

It was most unfortunate that Professor Kosorotov's post-mortem was brought to an abrupt halt on the orders of the tsarina. But the professor did have time to photograph the corpse and to inspect the bullet entry wounds. He noted that they "came from different calibre revolvers."

On the night of the murder, Yusupov was in possession of Grand Duke Dmitrii's Browning, while Purishkevich had a Sauvage. Either of these weapons could have caused the wounds to Rasputin's liver and kidney. But the fatal gunshot wound to Rasputin's head was not caused by an automatic weapon: it could only have come from a revolver. Forensic scientists and ballistic experts agree that the grazing around the wound was consistent with that which is left by a lead, non-jacketed bullet fired at point-blank range.

They also agree that the gun was almost certainly a British-made .455 Webley revolver. This was the favourite gun of Oswald Rayner, a close friend of Yusupov since the days when they had both studied at Oxford University.

Student Activities

Russian Revolution Simmulation

Bloody Sunday (Answer Commentary)

1905 Russian Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Russia and the First World War (Answer Commentary)

The Life and Death of Rasputin (Answer Commentary)

The Coal Industry: 1600-1925 (Answer Commentary)

Women in the Coalmines (Answer Commentary)

Child Labour in the Collieries (Answer Commentary)

Child Labour Simulation (Teacher Notes)

The Chartists (Answer Commentary)

Women and the Chartist Movement (Answer Commentary)

Road Transport and the Industrial Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Canal Mania (Answer Commentary)

Early Development of the Railways (Answer Commentary)

Health Problems in Industrial Towns (Answer Commentary)

Public Health Reform in the 19th century (Answer Commentary)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)

The Luddites: 1775-1825 (Answer Commentary)

The Plight of the Handloom Weavers (Answer Commentary)

1832 Reform Act and the House of Lords (Answer Commentary)

Benjamin Disraeli and the 1867 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

William Gladstone and the 1884 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)