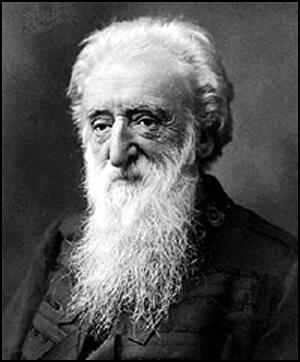

William Booth

William Booth, son of a builder, was born in Nottingham in 1829. At the age of fifteen he was converted to Christianity and became a revivalist preacher. In 1849 he moved to London where he found work in a pawnbroker's shop at Walworth. Booth developed strong views on the role of church ministers believing they should be "loosing the chains of injustice, freeing the captive and oppressed, sharing food and home, clothing the naked, and carrying out family responsibilities."

In 1852 Booth met Catherine Mumford. Catherine shared William's commitment to social reform but disagreed with his views on women. On one occasion she objected to William describing women as the "weaker sex". William was also opposed to the idea of women preachers. When Catherine argued with William about this he added that although he would not stop Catherine from preaching he would "not like it". Despite their disagreements about the role of women in the church, the couple married on 16th June 1855, at Stockwell New Chapel.

It was not until 1860 that Catherine Booth first started to preach. One day in Gateshead Bethseda Chapel, a strange compulsion seized her and she felt she must rise and speak. Catherine's sermon was so impressive that William Booth changed his mind about women's preachers. Catherine soon developed a reputation as an outstanding speaker but many Christians were outraged by the idea. As Catherine pointed out at that time it was believed that a woman's place was in the home and "any respectable woman who raised her voice in public risked grave censure."

In 1865 William and Catherine founded the Whitechapel Christian Mission in London's East End to help feed and house the poor. The mission was reorganized in 1878 along military lines, with the preachers known as officers and Booth as the general. After this the group became known as the Salvation Army.

William Booth sought to bring into his worship services an informal atmosphere that would encourage new converts. Joyous singing, instrumental music, clapping of hands and an invitation to repent characterized Salvation Army meetings.

General Booth was deeply influenced by his wife Catherine Booth, who believed that women were equal to men and it was only inadequate education and social custom that made them men's intellectual inferiors. She was an inspiring speaker and helped to promote the idea of women preachers. The Salvation Army gave women equal responsibility with men for preaching and welfare work and on one occasion William Booth remarked that: "My best men are women!"

The Church of England were at first extremely hostile to Booth's activities. Lord Shaftesbury, a leading politician and evangelist, described William Booth as the "Anti-Christ". One of the main complaints against Booth was his "elevation of women to man's status". Members of the Salvation Army were imprisoned for open-air preaching and their support for the Temperance Society made them the target for gangs of men who became known as the Skeleton Army.

William and Catherine Booth were also active in the campaign to improving the working conditions of women working at the Bryant & May factory in the East End. Not only were these women only earning 1s. 4d. for a sixteen hour day, they were also risking their health when they dipped their match-heads in the yellow phosphorus supplied by manufacturers such as Bryant & May. A large number of these women suffered from 'Phossy Jaw' (necrosis of the bone) caused by the toxic fumes of the yellow phosphorus. The whole side of the face turned green and then black, discharging foul-smelling pus and finally death.

William Booth pointed out that most other European countries produced matches tipped with harmless red phosphorus. Bryant & May responded that these matches were more expensive and that people would be unwilling to pay these higher prices.

In 1891 the Salvation Army opened its own match-factory in Old Ford, East London. Only using harmless red phosphorus, the workers were soon producing six million boxes a year. Whereas Bryant & May paid their workers just over twopence a gross, the Salvation Army paid their employees twice this amount.

William Booth organised conducted tours of MPs and journalists round this 'model' factory. He also took them to the homes of those "sweated workers" who were working eleven and twelve hours a day producing matches for companies like Bryant & May. The bad publicity that the company received forced the company to reconsider its actions. In 1901, Gilbert Bartholomew, managing director of Bryant & May, announced it had stopped used yellow phosphorus.

Gradually opinion on William Booth's activities changed. He was made a freeman of London, granted a honorary degree from Oxford University and in 1902 was invited to attend the coronation of Edward VII. When William Booth died in 1912, his eldest son, William Bramwell Booth, became the leader of the Salvation Army.

Primary Sources

(1) William Booth, In Darkest England (1890)

The citizens in Darkest England, for whom I appeal, are (1) those who, having no capital or income of their own, would in a month be dead with sheer starvation were they exclusively dependent upon the money earned by their own work; and (2) those who by their utmost exertions are unable to attain the regulation allowance of food which the law prescribes as indispensable even for the worst criminals in our gaols.

According to Lord Brabazon "between two and three millions of our population are always pauperised and degraded." Mr. Chamberlain says there is a "population equal to that of the metropolis" that is between four and five millions "which has remained constantly in a state of abject destitution and misery". Darkest England, then, has a vast despairing multitude in a condition nominally free, but really enslaved - these it is whom we have to say.

(2) William Booth, In Darkest England (1890)

The town-bred child is at a thousand disadvantages compared with his cousin in the county. But every year there are more town-bred children and fewer cousins in the county. To rear healthy children you want first a home; secondly, milk; thirdly, fresh air; and fourthly, exercise under the green trees and blue sky. All these things every country labourer's child possesses, or used to possess. In towns tea and slops and beer take the place of milk, and the bone and sinew of the next generation are sapped from the cradle.

(3) William Booth, In Darkest England (1890)

The home is largely destroyed where the mother follows the father into the factory, and where the hours of labour are so long that they have no time to see their children. The omnibus drivers of London, for instance, what time have they for discharging the daily duties of parentage to their little ones? How can a man who is on his omnibus from fourteen to sixteen hours a day have time to be a father to his children in any sense of the word? He has hardly a chance to see them except when they are asleep. Many of the new industries which have been started or developed since I was a boy ignore man's need to one day's rest in seven. the railway, the post-office, the tramway all compel some of the employees to be content with less than the divinely appointed minimum of leisure.

(4) William Booth, In Darkest England (1890)

Whatever may be thought of the possibility of doing anything with the adults, it is universally admitted that there is hope for the children. "I regard the existing generation as lost," said a leading Liberal statesman. "Nothing can be done with men and women who have grown up under the present demoralising conditions. My only hope is that the children may have a better chance. Education will do much." But unfortunately the demoralising circumstances of the children are not being improved - are, indeed, rather, in many respects, being made worse.

It will be said, the child today has the inestimable advantage of education. No; he has not. Educated the children are not. They are pressed through "standards", which exact a certain acquaintance with A B C and pothooks and figures, but educated they are not in the sense of the development of their latent capacities so as to make them capable for the discharge of their duties in life.

(5) Philip Gibbs, a journalist for the Daily Mail met General Booth in 1902.

His spirit was like a white flame. He had a burning fire within him. There was nothing of the gentle saint about him, and sometimes he had a terrifying anger, as once I saw, which scorched and blasted those who had betrayed him or had done some dirty work.

On the day I went to see him, on behalf of the Daily Mail, he started by being angry, and then softened. Presently he seized me by the wrist and dragged me down to my knees besides him. "Let us pray for Alfred Harmsworth," he said. He prayed long and earnestly for Harmsworth, and Fleet Street, and the newspaper Press that it might be inspired by the love of truth and charity and the Spirit of the Lord.

(6) William Booth, In Darkest England (1890)

Category

Description

East London

Rest of London

Total

Paupers

inmates of workhouses, asylums, etc. 17,000

34,000

51,000

Homeless

loafers, casuals, etc. 11,000

22,000

33,000

Starving

casual earnings between 18s and below 100,000

200,000

300,000

Very Poor

intermittently earning 18s. to 21s. per week 74,000

148,000

222,000

(7) William Booth published details In Darkest England of a survey into the reasons why young unmarried women in his rescue homes had become pregnant.

Cause of Pregnancy

Percentage of those interviewed

alcohol

14%

seduced by man

33%

willful choice

24%

bad company

27%

poverty

2%