The Longbow

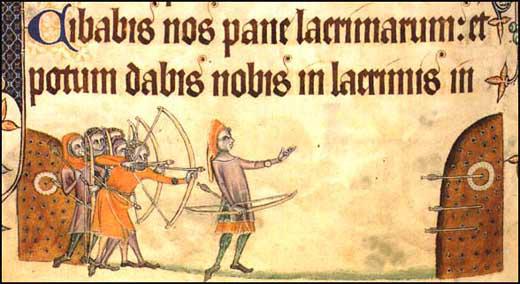

Bows had been used for thousands of years, but the first record of the longbows being employed in warfare was in South Wales during the late 12th century. In 1188 William de Braose, an English knight fighting the Welsh, reported that an arrow had penetrated his chain mail and clothing, passed through his thigh and saddle and finally entered his horse. The English now realised that even mail-clad knights were not safe from the power of the longbow.

The longbow was soon adopted by the English army. Unlike previous bows, the longbow was longer than the man who used it. Depending on the size of the archer, the longbow could be over 1.85 metres (6 feet) long. Another feature of the longbow was that the string was pulled back to the ear rather than to the front of the chest. This increased both the range and power of the arrow. As well as penetrating armour, the longbow arrow cold hit a target 320 metres (350 yards) away. Archers could therefore kill enemy soldiers before they were in a position to attack.

When the longbowmen entered the battlefield, they usually carried several sheaths holding 24 arrows. The arrowheads were made of iron and were about 5 centimetres (2 inches) long. The sheath would contain a variety of arrows of different lengths, weights and feathers. The arrow selected by the archer depended on the weather conditions and the distance of the intended victim. If longbowmen were captured, the opponents would cut off their thumbs and the first two fingers on the right hand to ensure that they never used a longbow again.

In an attempt to make the English the best longbowmen in the world, a law was passed ordering all men earning less than 100 pence a year to own a longbow. Every village had to arrange for a space to be set aside for men to practice using their longbows.

It was especially important for boys to take up archery at a young age. It was believed that to obtain the necessary rhythm of "laying the body into the bow" the body needed to be young and flexible. It was said that when a young man could hit a squirrel at 100 paces he was ready to join the king's army.

In 1314, Edward II became concerned by reports that young people were more interested in playing a new game called football than practising archery. King Edward's answer to this problem was to ban football in England.

Edward II also banned the playing of the game. His father, Edward III, reintroduced the ban in 1331 in preparation for an invasion of Scotland. Henry IV was the next monarch who tried to stop England's young men from playing football when he issued a new ban in 1388. This was ineffective and in 1410 his government imposed a fine of 20s and six days' imprisonment on those caught playing football. In 1414, his son, Henry V, introduced a further proclamation ordering men to practise archery rather than football. The following year Henry's archers played an important role in the defeat of the French at Agincourt.

Edward IV was another strong opponent of football. In 1477 he passed a law that stipulated that "no person shall practise any unlawful games such as dice, quoits, football and such games, but that every strong and able-bodied person shall practise with bow for the reason that the national defence depends upon such bowmen."