Herbert Gough

Herbert John Gough, the son of a lowly civil servant in the Post Office, was born in Bermondsey, London, on 26th April, 1890. Gough attended the Regent Street Polytechnic, and won a scholarship to University College. In 1909, he became an apprentice at Vickers in 1913. He eventually graduated from the University of London, with a BSc, a DSc and PhD in engineering. (1)

Gough learned to draw, design and construct gun mountings and fire control gear and in 1914 he joined the Engineering Department of the National Physical Laboratory (NPL), the country's leading research institute for the practical application of physics. (2)

On the outbreak of the First World War he joined the Royal Engineers. He was sent to the Western Front and in 1916 was commissioned as a lieutenant. He commanded a signal section and was in charge of communications, including at the Somme. He was twice mentioned in dispatches, and was awarded the MBE. He married Sybil Holmes in 1918, and they had a son and a daughter. (3)

Herbert Gough and Metal Fatigue

Gough returned to the National Physical Laboratory and became a specialist in metal fatigue. "This was a common problem in industry, which had need of practical solutions to the problem of failures in chains and cables. Gough was to make numerous contributions to the understanding of stresses in hooks, rings and other lifting gear, as well as to the causes of fretting and corrosion. His particular interest was in fatigue failure: that due to repeated applications of loads much lower than needed to induce immediate failure." (4)

In 1938 Gough was appointed as Director-General of Scientific Research at the Ministry of Supply. According to his biographer: "Gough's colleagues speak of the energy, drive, and enthusiasm that he brought to all that he did. He was by all accounts a strong and forceful personality and applied himself with equal energy to the study of the fatigue of metals and to an analysis of his golf score." (5)

Director-General of Scientific Research

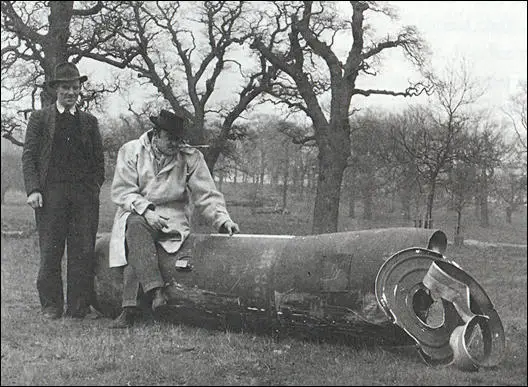

On the outbreak of the Second World War the post of Director-General of Scientific Research became more important. Gough and three other colleagues from the Royal Engineers, dealt with the first two unexploded bombs dropped on England in November 1939. (6)

One of the consequences of the Blitz was that by September 1940 there were 3,759 unexploded bombs in London. At first the main reason for this was faulty mechanism. However, within a few weeks it became clear that Germany had changed its strategy. Some bombs had been fitted with a sophisticated time-delay mechanism instead of a simple impact fuse. This was to ensure that the bombs would cause maximum havoc in the area where they fell, with premises evacuated and roads closed until they could be defused or moved to the "bomb cemetery". (7)

The government decided that a Unexploded Bomb Committee (UXBC) should be formed under the chairmanship of Dr. Herbert Gough, who then set-up a Research Sub-Committee (RSC), a weekly conference of scientists from the key ministries and laboratories that could react more swiftly to technical problems requiring rapid solutions. This included the co-ordinating of experimentation on fuzes. (8)

The Germans began dropping bombs with two fuze pockets. The first being the time delay (fuze 17) and the second the anti-handling fuze 50 that required a movement of less than a millimetre to activate the trembler switch. The process of attaching the unwieldy clock-stopper was more than enough to cause the 50 fuze to detonate. Scientists working on the problem developed a BD discharger. A mixture of alcohol, benzine and salt was forced into the fuze and if left for thirty minutes, the fuze would become inert and the clock-stopper could be attached. (9)

In September, 1940, George VI announced that "in order that they (Civil Defence workers) should be worthily and promptly recognised, I have decided to create, at once, a new mark of honour for men and women in all weeks of civilian life" for valour on the home front, as there were medals for those at the battlefront. The George Cross was intended to be the civilian equivalent of the Victoria Cross, which was awarded for "acts of the greatest heroism or of the most conspicuous courage in circumstances of extreme danger" Most of the medals went to members of the bomb disposal squads. (10)

Charles Howard, the 20th Duke of Suffolk

Charles Howard, the 20th Duke of Suffolk, attempted to join the Scots Guards but was rejected because he had previously had rheumatic fever. (11) He used family connections to be granted an interview with Herbert Gough, at the Ministry of Supply. He later recalled: "I was frightened at being landed with a titled member of Society about whom I knew so little. Such work as ours could carry no one who was not there on technical merit. In that frame of mind I saw Suffolk. His enthusiasm was tremendous. Before long his infectious personality, his gay buccaneering spirit won me completely." (12)

The government decided that a Unexploded Bomb Committee (UXBC) should be formed under the chairmanship of Gough. He then set-up a Research Sub-Committee (RSC), a weekly conference of scientists from the key ministries and laboratories that could react more swiftly to technical problems requiring rapid solutions. This included the co-ordinating of experimentation on fuzes. One of the RSC's first decisions was to commission a company to produce a "fuze discharger". (13)

Charles Howard became aware of the UXBC and asked Gough if he could get involved in this work. When an unexploded bomb fell on Deptford Power Station Gough took Suffolk with him. "The highly-dangerous 'game' of removing fuses became the young earl's new occupation. Dr. Gough formed the first and only Experimental Field Unit, and put Suffolk in charge of it. As raid after raid left in his wake deadly unexploded bombs, Suffolk and his men would remove the fuses and send more interesting examples to H.Q. for examination." (14)

M. J. Jappy, the author of Danger UXB (2001) has pointed out: "Dr Gough at the Ministry of Supply set Lord Suffolk out on what was to be his most daring venture yet: the world of bomb disposal. His health had prevented him going on active service but with characteristic disregard for rules and regulations, he bought himself a large van and kitted it out with the necessary equipment to investigate methods of defuzing unexploded bombs. His high level connections aided his maverick approach and eventually a small team of soldiers was seconded to him to help him with his work." (15)

The Duke of Suffolk's detachment consisted of himself, his secretary Eileen Beryl Morden, and his chauffeur, Fred Hards. The first scheme that Gough asked Suffolk to devise was a method for burning out the filling from bombs that could be steamed out, or where corrosion prevented the removal of the base plate by hand. To do this a "beaked crucible containing about six pounds of thermite was placed about three or four inches above the nose weld of the bomb casting". (16)

Over the next few months successfully dealt with 34 unexploded bombs. He was described as being "tall and debonair, often wearing a stetson, fawn duffel coat and sporting a matinee idol moustache, Howard would smoke with his 9-inch cigarette holder as he pondered the latest UXB." (17) Harold Macmillan later recalled: "I have had the good fortune to meet many gallant officers and brave men, but I have never known such a remarkable combination in a single man of courage, expert knowledge and indefinable charm." (18)

James Owen, the author of Danger UXB: The Heroic Story of the WWII Bomb Disposal Teams (2010), has pointed out that his bomb disposal work was sometimes criticised: "One officer accused him of carelessness after a five-hundred-kilogram bomb half wrecked a house while Suffolk was trying to neutralise its fuze with gelignite. The Earl did his best to defend himself against the charge that his team were meddlers. A few weeks later, however, a detachment of the East Surreys stationed in Richmond Park complained about several violent explosions set off by Suffolk that had, without warning, sprayed red-hot metal close to the guard room and officers' mess." (19)

Herbert Gough admitted that "he (Suffolk) gave the appearance of being slapdash at times". Lieutenant John Hudson of the bomb disposal unit, was another person who had misgivings about the Duke of Suffolk's approach: "He was a very colourful, very odd man. He used to have a pistol in a holster under his arm and when he wanted his van he would fire his pistol twice in the air, that sort of thing. He had a very pretty girl as a sort of secretary, we all envied him her... We didn't care for Suffolk at all. He wasn't disciplined, and he wasn't one of us." (20)

One of the major criticisms of Suffolk was that he took unnecessary risks: "His apparent disregard for the safety of those around him was anathema to the officers of the Royal Engineers. The regulations were clear: only those who were absolutely necessary should be in the vicinity when defuzing was taking place. It was very rare indeed for there to be any more than one person anywhere near the bomb after it had been uncovered." (21)

On Tuesday, 12th May, 1941, a bomb for examination by Lord Suffolk's squad was taken to the Belvedere Marshes, just outside south-east London. It was an aged bomb, about 18 months old, and very rusty. A stethoscope was called for and preparations were made to sterilize the bomb. The bomb exploded at 3.20 pm and created a crater 5 ft in diameter. Suffolk and seven sappers were killed immediately. Rescuers found "Beryl Morden in an extremely serious condition. Fred Hands had managed to drag himself a few yards and died calling for Suffolk... Beryl, who had been in the service of the Earl for eleven months, sadly succumbed to her injuries and died in the ambulance." (22)

There were fourteen people around the bomb when it exploded. No trace at all could afterwards be found of four of them. "Some fragments of clothing and feet were identified as belonging to Suffolk, but in essence all that survived of him was the silver cigarette case." Among the dead were Staff Sergeant Jim Atkins, who had been operating the stethoscope, as well as Sappers Jack Hardy, Reg Dutson and Bert Gillett, and Driver David Sharratt. Six other soldiers had very serious injuries. (23)

A bomb disposal expert, William Wells, later argued: "It seemed a blunder on the part of the higher authorities to employ Lord Suffolk on bomb disposal experiments. He was a courageous man, but too adventurous, too much the showman for the cold-bloodied business of bomb disposal experimental work." Lieutenant John Hudson agreed: "We were all very thankful to have him off our chests, but we were very sorry that he took a lot of our chaps with him... He was an amateur, the one and only amateur bomb disposer... I mean, to have people standing around watching you in bomb disposal just wasn't done." (24)

Unilever

In 1945 Gough joined Unilever as engineer-in-chief. Gough's responsibilities at the ministry were very wide, for they concerned physical research, signals, and chemical research, and included the Radar Research Station, under John Cockcroft, the chemical station at Porton Down, under Davidson Pratt, and the Aberporth Rocket Station, under Alwyn Crow. Gough retired from Unilever in 1955. (25)

Herbert John Gough died suddenly at the Royal Sussex County Hospital, Brighton, on 1st June 1965.

Primary Sources

(1) Herbert Gough : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (23rd September, 2004)

In 1914 Gough joined the staff of the National Physical Laboratory (NPL), Teddington, Middlesex, in the engineering department, where he stayed until 1938, becoming superintendent of the department in 1930 in succession to Sir Thomas Stanton. During the First World War Gough served in the Royal Engineers (signals) from 1914 until May 1919, rose to the rank of captain, and was twice mentioned in dispatches. He was appointed MBE (military) in 1919.

During his period at the NPL Gough established the science of the behaviour of materials under fatigue conditions. Fatigue failure is failure due to repeated application of a load much lower than that necessary to produce failure in a single application and is one of the most frequent causes of breakage in service. Gough, working initially under the inspiration of Stanton and with many able young scientists and engineers such as D. Hanson, H. L. Cox, A. J. Murphy, C. E. Elam, and W. A. Wood, established that fatigue failure occurs because the metal undergoes plastic deformation. He discovered that this was due to slippage inside the metal crystals and, using X-rays (a new tool at the time), showed how safe ranges of stress could be forecast. He also attacked the problem of fatigue under conditions when differently directed stresses are applied simultaneously, explaining how to predict ‘lives’ under these conditions. Having developed means of estimating stresses in chains, hooks, and rings, Gough applied the principles to the design of lifting gear. He also demonstrated how the designer of mechanical structures needs to allow for the increased stresses arising at fillets, lubrication holes, keyways, and splines. All of this work was of immense practical significance for it enabled designs to be much more economic, replacing rule of thumb by quantitative procedures. Gough also investigated fretting corrosion where moving metal parts touch, cold pressing of metals, lubrication, and welding. He published The Fatigue of Metals in 1924 but much of his later work was not widely known until the publication of his presidential address to the Institution of Mechanical Engineers in 1949.

(2) The Liverpool Echo (2nd July, 1955)

All through World War II, and four a long time after it, countless lives were saved by a group of selfless, silent men - the volunteer heroes of bomb disposal units, the scientists and engineers who worked continuously in the shadow of sudden death. Many of these brave men did lose their lives in the pursuit of their hazardous work, but there were always others ready and willing to take their place.

Between 1940 and 1945, no fewer than 50,000 unexploded bombs were examined and disposed of in Great Britain alone. Among the fearless pioneers whose sensitive hands unravelled the mysteries of each new and terrifying fuse was Charles Henry Howard, 20th Earl of Suffolk and 13th Earl of Berkshire...

When war came in 1939, Lord Suffolk was rejected as unfit for military service: his earlier illness had left its mark. However, a close friend recommended him to the Ministry of Suupply, and his character, enthusiasm and learning made a deep impression on Dr. Herbert J. Gough, Director-General of Scientific Research. Dr. Gough was not concerned with titles; he simply wanted the best man he could get.

Lord Suffolk wanted impatiently for a new opportunity to serve his country. It came when an unexploded bomb fell on Deptford Power Station. Dr. Gough went to see it and Suffolk joined him. The highly-dangerous "game" of removing fuses became the young earl's new occupation. Dr. Gough formed the first and only Experimental Field Unit, and put Suffolk in charge of it. As raid after raid left in his wake deadly unexploded bombs, Suffolk and his men would remove the fuses and send more interesting examples to H.Q. for examination.

Suffolk revelled in his work, but was always conscious of its extreme danger. Often, he would order his men to a safe distance while he worked on alone.

At home, he never mentioned his own efforts, but sang the praises of his team of seven assistants. Off duty, he would often entertain them at a private party, and its says much of his leadership and discipline was never relaxed. A wonderful spirit bound him and his men together - whether working with fuses, burning into bombs, experimenting with oxy-acetylene burning, or sawing bombs in two.

But on Tuesday, May 12, 1941, a bomb for examination by Lord Suffolk's squad was taken to the "Marshes", just outside south-east London. It was an aged bomb, about 18 months old, and very rusty Dr. Gough was a little nervous about it, and drove to the "Marshes" to assure himself that Lord Suffolk was taking every possible precaution. When he got back to his office, however, he was greeted with the tragic news that the bomb had exploded and that Suffolk and his gallant men were dead.