Hede Massing

Hede Tune (Hede Massing), the daughter of a Polish father and an Austrian mother was born in Vienna in 1900. "Mother was the daughter of a well-to-do and highly respected rabbi in Poland. Her parents had died when she was seven, and she had then joined her older brother, Max, in Vienna." (1)

Soon after he birth her parents emigrated to the United States. Her father established a business in Fall River, Massachusetts. "He was in partnership with a caterer. By then he had started to gamble and to philander. When his business failed, they moved to New York. She (my mother) could never quite tell me what they did in New York and how they lived, except that she was painfully lonely and homesick for Vienna." (2) The family returned to Austria in 1907.

Hede was frustrated by the lack of interest her parents took in her education: "My parents, so occupied with their own problems, never paid much attention to any of my successes or failures in school... In 1914, my last year in high school and the time to decide whether I was to go on with school or learn a trade." Hede obtained a job in a millinery shop. "My apprenticeship in the millinery shop proved to be a complete failure. I was again, as I had been in school and as was going to be ever so often in life, quite out of place. I did not like hats (I still have the aversion), and I did not like the girls in the shop. And I am sure that they did not like me. They thought me pretentious and stand-offish." (3)

Hede never got on well with her father: "My father was a handsome man. I inherited from him only his height, his reddish curly hair, and, alas!, probably some of his less attractive character traits. Whenever I have become aware of them, I have tried to tear them out of me. Long after I had left home, my sister Elli once remarked that I danced like Papa. I stopped dancing for years.... He is, to me, the personification of flightiness, instability, and insecurity. It is in reaction to him that I have never in my life gambled in any form whatsoever, that I do not know how to play cards or any other competitive game.... He left my mother shortly before the end of the first world war. I have not heard from him since." (4)

Gerhart Eisler

That summer Hede met a left-wing law student, Victor Stadler. He introduced her to the work of Karl Kraus. "At that time Karl Kraus seemed to a number of us young people the most influential and outstanding thinker and writer of Vienna. He was editor and publisher of the magazine, Die Fackel, or The Torch, and had great influence in forming the attitude and thinking of my generation. His most effective medium was satire, but he was a fine poet and dramatist. He was also a superb actor. During his performances (one could not call them lectures), which were held regularly in the Kleinen Konzerthaussaal, a small, graceful auditorium, he read, or better, dramatized the Austrian classics." (5) Kraus also promoted the work of left-wing playwrights, Bertolt Brecht, Frank Wedekind and Gerhart Hauptmann.

During this period she met Gerhart Eisler a member of the Austrian Communist Party. His brother Hans Eisler. and sister, Ruth Fischer, were also members of the party. "It began one evening, when tall, handsome Stachek came to my table in the cafe with a short, but appealing young man and introduced him, proudly, as the famous Gerhart. Of course, I had imagined him very differently. I probably thought him tall and dashing but instead he was small, squat and had a slight lisp which irritated at first, but which I later came to think of as something exquisitly charming. This slight imperfection softened his otherwise complete, undeniable perfection. He did have very beautiful eyes. Even in later years, when he had become a tough politician, his eyes contrasted sharply with his whole personality. They were large blue eyes, with heavy eyebrows and long, curving dark eyelashes." (6)

A few days later Gerhart Eisler told her, "Hede, I am going to tell you something quite different from what all the other young men around you have told you. I love you; I want you to share my life. It is not going to be a soft and easy one. I am a revolutionary. I have dedicated my life to a great idea, the greatest, in fact, the idea of socialism. When you understand more about it, you will know that there will be little time for anything but this one great cause! I will take you away from your home right now. I shall take you to my family and you will stay with them until we can set up house for ourselves, wherever that may be....How do you feel about that?"

Hede recalled in her autobiography, This Deception: KBG Targets America (1951): "It was hard for me to say how I felt. I was pleased and happy that Gerhart loved me. But the thing that was much more important and that still stands out as the important gesture of a Communist, even in retrospect, was that he wanted to take me away from the misery and unhappiness of my own family and bring me to his sweet and gentle mother, as he said, and his shy and professorial father. They were to give me the feeling of a family, that I had missed so deeply." (7)

Hede married Eisler in December 1920. They went to live with his parents in Vienna. They made her feel very welcome: "Soon I was a full-fledged member of the Eisler household. I shared the duties and the pleasures of the Eislers. It was a completely new life, the life of an intellectual family, with constant discussions about books and music and politics. I was very happy. I went to the café much less frequently; instead I attended meetings of the small and select groups of the Communist party in Vienna... Under Gerhart's influence, I started to read more serious books than I had read until then." (8)

German Communist Party

Gerhart Eisler became editor of The Communist, the party's serious theoretical journal. In January 1921 he was asked to be associate editor of the Die Rote Fahne, a newspaper founded by Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht. It was Germany's leading left-wing newspaper. The couple married and moved to Berlin and joined the German Communist Party (KPD). Hede Eisler found work as an actress. Her first part was as Gwendolyn in The Importance of Being Earnest.

(If you are enjoying this article, please feel free to share. You can follow John Simkin on Twitter and Google+ or subscribe to our monthly newsletter.)

Hede became more involved in politics and spent hours discussing politics with her husband and sister-in-law, Ruth Fischer. She claimed later that her hero was Vera Figner, who had been involved in the assassination of Tsar Alexander II in 1881. "I read about the Russian Revolution, about Lenin and Vera Figner, who became my idol; and I learned to love the idea of socialism the idea of a better life for everyone. True, I never faced the reality of everyday work within the movement. I moved only among the upper crust of the Communists... I was imbued with the rather snobbish attitude of Gerhart to people who were not as bright as he was."

Julian Gumperz

Hede Eisler left Gerhart Eisler and in 1923 she moved in with Julian Gumperz. In her autobiography she described him as being refined, softspoken, and a sensitive young man, not hardened by politics although he too then belonged to the left circle." (10) Gumperz also joined forces with Wieland Herzfelde and John Heartfield to establish the left-wing publishing company, Malik Verlag. Massing explained the thinking behind the business venture: "Their aim was to bring inexpensive good books to the masses. They put out handsome paper-bound editions of all left or progressive literature and created quite a furor in the German publishing world. The design of their books was extremely original and was in later years copied by many of the more conservative publishing firms. In fact, it was they who introduced the paper-bound book... Though it employed many Communists and published many of their works, it was financially and politically independent of the Party. As a matter of fact, they had many disagreement with the Party, which made every attempt to incorporate the Malik Verlag into its orbit." Malik Verlag was so successful that it also opened a bookshop and art gallery in Berlin. (11)

Alexander Ludwig, Konstantin Zetkin, Georg Lukács, Julian Gumperz,

Richard Sorge, Karl Alexander (child), Felix Weil, unknown; sitting: Karl August

Wittfogel, Rose Wittfogel, unknown, Christiane Sorge, Karl Korsch, Hedda Korsch,

Käthe Weil, Margarete Lissauer, Bela Fogarasi, Gertrud Alexander (1922)

Hede married Gumperz and his mother bought them a house in Lichterfelde-West, a suburb of Berlin. Hede's sister, Elli Tune, who was fifteen at the time, moved in with them. Gerhart Eisler, lost his job with Die Rote Fahne as a result of a factional disagreement. Hede later recalled: "He (Gerhart) was not only psychologically disturbed but in financial straits, and Julian, always ready to help, suggested that Gerhart move to our house until he had regained his bearings and found himself a new job."

Gerhart Eisler eventually got a new job at the Soviet embassy in Berlin. His official job was as a political analyst but he had actually been recruited as a spy. According to Hede he now met many Russians and gradually obtained their trust: "But he was not in the power of the Russians yet. He was still independent in his thinking, an honest revolutionary, with due respect to the Russians, and sympathy for their difficulties, but the faith of the German party was his main concern." (12)

While living in Gumperz's home, Gerhart Eisler began a relationship with Hede's sister, Elli Tune: "Gerhart assumed the father role for Elli and me, and Julian was my husband. The world was fine. Gerhart was completely in charge of Elli and I considered her fortunate to have such a tutor. Now, I have come to realize that I am fairly observant of many things, but extremely stupid and unimaginative when it comes to other people's love affairs... So I did not notice at all that Gerhart and Eli were lovers until I was told that they were." (13)

In 1925 Julian Gumperz was asked to supervise all the publishing of the German Communist Party (KPD). As part of his new responsibility he had to make regular visits to the Soviet Union, as all publishing of the KPD had to be approved by Moscow. He gradually became disillusioned with the way that the country had changed since the death of Lenin. In 1926 he decided to return to the United States. Hede and Julian Gumperz arrived in New York City in August 1926.

Soon after arriving in America they met Michael Gold, a journalist who worked for The New Masses. Gold arranged for Hede to work in an orphanage in Pleasantville. "It was a wonderful experience. It was my first job of that kind with children, underprivileged children at that, and I loved it. Had I been smarter, I would have stuck to this sort of work and gone on to school to become a social worker." In December 1927 Hede Gumperz was granted American citizenship.

Paul Massing

In January 1928, Hede and Julian Gumperz returned to Germany. Julian had obtained a job teaching at the Institute of Social Research in Frankfurt am Main. They associated with members of a Marxist student group and during this period they met Paul Massing. "At the time I met him, he had just spent a year at the Sorbonne in Paris preparing for his Ph.D. and was about to finish.... Julian thought him a rare combination of peasant boy and intellectual and was so interested in him that he helped to tutor him in preparation for the orals before his doctor's examinations. These sessions were at our house and it was then that I got to know him better. I did not think him so exceedingly good looking at first. Neither did I think him so outstandingly brilliant as I had been led to expect. He had a quick wit and a great capacity for laughter - a loud and attractive sort of laughter. I liked his rakish way of wearing his little French cap, and the way he walked; the seriousness of his face with the high cheekbones that gave him a Slavic look, and that sudden change of expression to a boyish devilishness when he was amused or ironical."

It was not long before Hede had fallen in love with Massing: "My relationship with Paul grew like something so natural and so completely uncontrollable that it is almost impossible to recall how it started. Its beginning is clouded and veiled, as is, I suppose, the beginning of all great passions; something that should not be probed or searched for, but left complete and untouched as in sacred keeping. I remember our first walk, arm in arm, and how pleased he was that we were both tall and kept the same step; the warmth and happiness I felt when I looked up to his face.... When he spoke of his mother, the tenderness and warmth that came from him. The love he had for his schoolfriends. The strength and earthiness he conveyed. Yes, Paul was different, he was made of a different fiber. I was awed. He did not have a ready made answer to everything. He was not so sure that the world would be better with communism, though he was preoccupying himself with finding out about it. He was not sure of anything much. Nothing was cut and dried. One had to find out about things. He was bright, inquisitive, enterprising, and truly, honestly modest." (14)

Hede now left Julian Gumperz and went to live with Paul Massing who had found a job writing for the International Agrarian Problems, a scientific monthly that financed and edited by the Agrarian Institute in Moscow. In 1929 Massing went to work for the Agrarian Institute. Hede remained in Germany and later that year she met her old friend, Richard Sorge. Over the next few weeks she spent a lot of time with Richard Sorge and his wife Christine. "There was a fine collection of modern paintings and rare lithographs. I was impressed by the easy atmosphere and grace with which the household was run. I liked the combination of serious talk, and lust for living that was shown."

According to Robert J. Lamphere it was Sorge who recruited her as a Soviet agent: "Sorge, formerly a Comintern man like Gerhart, had spirited his wife away from an older man, just as Paul had taken Hede from Julian. At dinner he convinced Hede that espionage was heroic and glamorous and that she, too, could do important things for the Party." Sorge introduced her to Ludwig (Ignaz Reiss), a senior figure in Comintern. "Ignace Reiss, a charming, erudite man who inspired near-fanatic loyalty on the part of Hede and many other agents. Together with his childhood friend Walter Krivitsky, Ludwig was a mainstay of Russian intelligence and had been so since the early 1920s. On his instructions Hede dropped her attendance at local Party meetings." (15)

Before she became an active spy, Hede joined Paul Massing in the Soviet Union. In 1930 she taught advanced German in the foreign-language school in Moscow. She was shocked by the shortage of food in Russia. "It was the time of the collectivization, the first Five-Year Plan, the mass arrests of kulaks and great gnawing hunger; the general misery was obvious... I learned and relearned continuously, at school through pupils, and at home with the Russian family. Careful and cautious as they were, they could not help but betray the great secret that they had almost nothing to eat." (16)

Hede Massing in Moscow

Hede and Paul Massing became disillusioned with life in the Soviet Union under Joseph Stalin. "In 1930 and 1931 everybody was hungry, had no clothes, no decent beds, no decent linen... True, there were some exceptions - the GPU (today the MVD) and the foreigners. It was also about this time when children were called upon to spy on their parents; to report negativism, derogatory remarks, religious inclinations, or religious services attended; to tell whether their mother really had been sick or had really just washed her clothes, cleaned her miserable dwelling, or even relaxed, instead of attending those endless, ludicrous meetings." (17)

While in Moscow the Massings became friends with Louis Fischer, the journalist who worked for The Nation. At the time he was still a strong supporter of Stalin and believed he was about to introduce democracy: "Though I violently dislike the raucous paeans of praise for Stalin which are repeated in this country with benumbing frequency and monotony. I must add mv voice to the chorus. Democratization is not a whim inspired by a moment or a bit of opportunism provoked by a temporary situation. Stalin apparently thought this out years ago. He has been preparing it ever since 1931. Forward-looking people abroad will hail the change toward democracy." (18)

Hede Massing also met her former husband, Gerhart Eisler, and his wife, Elli Eisler, who was also her sister, in Moscow. Eisler had recently been into exile because of his role in the Wittorf Scandal. In 1928 John Wittorf, an official of the German Communist Party (KPD), and a close friend and protégé of Ernst Thälmann, was discovered to be stealing money from the KPD. Thälmann tried to cover up the embezzlement. When this was discovered by Gerhart Eisler, Hugo Eberlein and Arthur Ewert, they arranged for Thälmann to be removed from the leadership. Joseph Stalin intervened and had Thälmann reinstated, signaling the removal of people of power of people like Eisler and completing the Stalinization of the KPD. Rose Levine-Meyer commented: "To make him the indisputable leader of the German Communism was to behead the movement and at the same time transform a highly attractive, able personality into a mere puppet." (19)

Stalin ordered Eisler to Moscow. He was now sent to China as the representative of the Comintern as a punishment for his attempts to remove Thälmann from the leadership. "I had also seen Gerhart Eisler and my sister Elli in Moscow.... I saw both of them when they had come back from China. Gerhart was sent to China as punishment. He was involved in the Wittdorf affair, a political maneuver to dethrone Ernst Thälmann, who was supported by Stalin. The maneuver miscarried, and the three instigators were dealt with in the following manner: After they had been kept in Moscow for some time, all three were completely divorced from German politics. Hugo Eberlein was kicked upstairs and became auditor of all European party funds. At that time, Stalin probably still respected the fact that Eberlein was married to Lenin's adopted daughter; later he was purged like all the other old-timers. Arthur Ewert was sent to Brazil, where he was caught in the putsch of Carlos Prestes. He was arrested, pitilessly tortured and lost his mind. He was supposedly freed a few years ago and taken to the Eastern zone of Germany where he disappeared. Gerhart was, after a time, in complete isolation in Moscow, forbidden to read German papers in order to get Germany out of his system, and then sent as Comintern representative to China where, according to many reports, he achieved great success through his ruthless policy. He stepped back into Stalin's favor." (20)

Hede Massing believed that this experience turned Gerhart Eisler into a loyal supporter of Joseph Stalin: "Gerhart was a different Gerhart. And it was China that had changed him. Today, I know that people become toughened by experience, that they take on habits, expressions, and mannerisms that life imposes on them. But Gerhart used to be so smart and observant! He would size up a situation in a flash and act accordingly. It was so very unlike him to be rude and a show-off. His modesty was gone and with it his interest in other people. I was shocked by his display of being in the know and his poorly veiled indications of how important a job he thought he had done. His insensitivity toward Paul and me, and toward the general situation in Russia which we attempted to point out to him, was so upsetting that I simply could not bear to listen to him. I asked him to leave. Paul, so much better mannered than I could ever hope to be, was furious, thought me hysterical; did not think that this was the way to behave or to settle any issues. The Eislers and the Massings were not on speaking terms for some time in Moscow. It was only when I learned that Gerhart had suffered a serious heart attack that I went to see him at the Kremlin hospital. (21)

Nazi Germany

In the spring of 1931 Hede and Paul Massing returned to Germany. He had been offered a contract to teach at the Marxistische Arbeiter Schule. "During the rear and a half that we had been away from Germany fascism had grown by leaps and bounds." Hede Massing recalled that the Völkischer Beobachter was displayed in every railway station and "people would pick them up and read them unashamedly". She noticed that there were continuous demonstations of the Nazi Party and the Hitler Youth.

Hede Massing was soon contacted by Ignaz Reiss, a senior figure in Comintern. Using the code name of Ludwig, he asked her to become a Soviet spy in the fight against Adolf Hitler. He told her: "Hede, times have changed; we will have to get busy. The first thing you must do is to drop out of the local party unit. And do not give them any explanation." At first she was reluctant: "It was the beginning of my work with Ludwig. There were still preliminaries, such as meeting him once a week to be retrained. All principal issues, tactics, behavior patterns were gone over. I used to come home and ask Paul what he thought about it, why there was nothing Ludwig would give me to do, just this endless, endless talk. He, too, wondered. Then followed a complete report on everybody I had known in the past and my new friends as well. This procedure is typical of the preliminary steps in the work of any new agent of the apparatus. Slowly, slowly, he had me set up the first mail drop, the first social contact, the first apartment for work, and finally he sent me on my first scouting trip." Massing had a great deal of respect for Reiss. "He was suave and gracious... I came to admire him immensely and to trust his judgments implicitly... I was always pleased to see him! His small, firm steps, the gesture of his hand greeting me, his smile, his bright blue eyes dancing when he thought I said something amusing." (22)

Massing was asked by another Comintern agent, Hugo Eberlein, to go to London to inspect the books of the Communist Party of Great Britain. "The party books had been deposited in a private home outside London... From time to time I called on party officials for explanation of various items in the accounts. As far as I can recall, everything balanced well enough. How glad the English comrades were when our mission was ended... In light of that experience, I am always amused when people debate as to whether individual individual Communist parties are really financed and controlled from Moscow headquarters. What did our mission amount to but an audit of a foreign branch house by the main business office?" (23)

In 1932 Hede Massing was asked to meet a senior figure in the NKVD in Berlin. "He was a dark, unimpressive little man whom Ludwig (Ignaz Reiss) treated with great deference... I gathered that he was looking me over for some special assignment. Evidently I did not pass muster, since the matter was not mentioned again." Massing later discovered that the man was General Walter Krivitsky, head of all Soviet intelligence in Western Europe.

Adolf Hitler was made Chancellor of the Reich on 30th January, 1933. The new government immediately suppressed the German Communist Party (KPD): "The city of Berlin changed its face. Comrades stayed away from the streets and from each other... All leading party members that had not fled were arrested and beaten to pulp in Columbia House. The first and best-known of all the Nazi torture chambers, Columbia House has become history. It is described in all the accounts of the plights of millions of Nazi victims." (24)

Paul Massing decided to stay in Berlin: "Paul had organized a small group of professors and scientists in the anti-fascist fight. He hoped to organize, with their help, a student body opposing Hitler at the universities. He was convinced that one must stay and do what one could. All my arguments in which I pointed out that he had been making speeches against the Nazis on so many platforms, that he was too well known in spite of the assumed name he had spoken under, were to no avail."

Hede Massing reached Paris but soon afterwards she had a telegram from Louis Fischer telling her that Paul had been arrested by the Gestapo. Hede, who was with Ignaz Reiss, decided to return to Nazi Germany. Paul was being held in Camp Oranienburg. Every day the prisoners were marched through the streets of Oranienburg. "He limped. He must have been crippled from the beatings. Nothing but his eyes and his nose were the same. His mouth was a line, thin and narrow, in his pitful shorn head." (25)

Hede Massing in the USA

Unable to help her husband, she was persuaded by the NKVD to join a spy network in the United States. She arrived in New York City in October 1933. She went to stay with Helen Black, the wife of Michael Gold, and the Soviet Photo Agency representative in America. Earl Browder visited Hede who told her "I want to make you feel at home here." Browder was disappointed when he discovered that Hede had not brought him money from the Soviet Union.

Hede Massing was put into contact with Harold Ware who introduced her to other members of the Communist underground. "Harold Ware, the son of the famous Communist leader, Mother Bloor, who also helpful in widening my capitol contacts. I did not know until many years later that he was the key operator in a Soviet network extending from the Department of Agriculture, where he worked, into the Treasury, State Department and the other government branches." (26)

Valentine Markin

Valentine Markin eventually made contact with Hede Massing. "Arthur Walter (Valentine Markin) was a youngish man, with high cheekbones, bad teeth, and a brushlike mop of mud-brown hair. His complexion was gray, his eyes cold. He struck one from the very beginning as a man who, with great energy, withheld his real self from observation, who surrounded himself with a thick, impregnable veneer. He was young to hold so commanding a position. He was the personification of a Russian careerist. I met many later, but none of them was as perfectly designed as was Markin. It was a fascinating character combination, one of extreme sentimentality when drunk and relaxed, and extreme cruelty when sober and on the job. His moral and ethical standards were typical of the young Soviet man; it is not the human being who counts, but the idea!" (27)

Markin had been involved in a dispute with General Yan Berzin, the head of the GRU. According to General Walter Krivitsky, head of all Soviet intelligence in Western Europe, Markin went to see Vyacheslav Molotov and exposed the incompetence of General Berzin and all his lieutenants in Military Intelligence. Gary Kern, the author of A Death in Washington: Walter G. Krivitsky and the Stalin Terror (2004), confirms this story: "Markin was a pushy egotist when sober and a slobbering sentimentalist when drunk, which was often, and he saw an opportunity to advance his career. He came back to Moscow with a report laying all the blame on the Fourth Department and with unprecedented effrontery took his case to higher-ups in the Kremlin, speaking directly with Vyacheslav Molotov, Stalin's right-hand man." (28) As a result of this meeting Joseph Stalin transferred military intelligence organization in America to the espionage machine of the GPU under Genrikh Yagoda, the head of the NKVD.

In December 1933, Paul Massing was released by the Nazi government. Hede returned to Europe and met him in Paris and they arrived in the United States in January 1934. Massing was the first person to be freed from a Nazi concentration camp to reach America and he was asked by John C. Farrar to write an account of his experiences. The couple took a cottage for the summer in Cos Cob, Connecticut. Massing's book, Fatherland was published the following year.

Valentine Markin died in August 1934. According to David Dallin, the author of Soviet Espionage (1955), he was found at the Luxor Baths on 46th Street in New York City "with an ugly head wound in a 52nd Street hallway in New York; he died the next day." (29) Whittaker Chambers was told by one of his agents that "Herman (Valentine Markin) had been drinking heavily. Late at night, he went, alone, into a cheap bar somewhere in midtown Manhattan. He drank more and flashed a big roll of bills. Two toughs followed him out of the saloon, and, on the deserted street, beat him up, robbed him and left him lying in the gutter. Herman died in a hospital of a fractured skull complicated by pneumonia." (30)

General Walter Krivitsky was initially told that Valentine Markin "had been slain in a New York nightclub by gangsters." However, in May, 1937, Abram Slutsky, the head of the Foreign Department of NKVD, told Krivitsky that Markin had been murdered because of his support of Leon Trotsky: "You know, it turned out that your friend, Valentine Markin, who was killed in New York three years ago, was a Trotzkyite, and filled the GPU services in the United States with Trotzkyites." (31)

Laurence Duggan & Noel Field

In her autobiography, This Deception: KBG Targets America (1951), Massing explained how Soviet espionage worked in the United States. "When I was an apparatchik I thought there were three separate Soviet espionage machines abroad. These I knew were kept carefully apart. One was Military Intelligence, the so-called Third Department. The second was the Comintern apparatus, guiding and guarding the Communist movement all over the world. Finally, there was the secret police apparatus, the Foreign Division of the GPU, with which I was connected. I have since been informed... that in 1934 the GPU became a department of the Commissariat of the Interior, the NKVD. It became the GUBG of the NKVD. In May, 1943, the GUBG of the NKVD was made an independent Commissariat of State Security and was called NKGB. In March, 1946, NKVD became a ministry, MVD, and NKGB became a ministry, MGB.... Naturally, I was never informed in so many words which of these machines I served, and it would have been an unthinkable blunder for me to inquire. But I knew, all the same, through a process of elimination." (32)

Iskhak Akhmerov arrived in New York City to replace Valentine Markin. He decided that Boris Bazarov should be the one to work with Hede Massing. She first met him in May 1935. He told her that that they wanted her to help recruit Laurence Duggan and Noel Field. The plan, suggested by Peter Gutzeit, the Soviet Consulate in New York City, was to use Duggan to draw Field into the network. Gutzeit wrote on 3rd October, 1934, that Duggan "is interesting us because through him one will be able to find a way toward Noel Field... of the State Department's European Department with whom Duggan is friendly." (33)

Hede Massing later recalled: "Of the conquests I made while a Soviet agent, the one I regret most is Larry Duggan... Larry and Helen lived in the same house, on the floor below the Fields and were their most intimate friends.... Larry was, when I first heard of him, in the Latin American Division of the State Department... Larry impressed me as being an extremely tense, high-strung, intellectual young man... His wife, Helen, beautiful, well balanced, capable and sure of herself, seemed the perfect counterpart to him. An excellent housekeeper and busy woman, she was an attentive and loving companion to Larry." (34)

Massing argued that "every decent liberal has a duty to participate in the fight against" Adolf Hitler. He agreed and then she told him she was a Soviet agent and suggested that he should give her "anything of interest" in his department. Duggan said that he "doubted that there would be anything and he showed some reluctance, but promised to think it over and let me know." They had lunch together a week later: "Much to my surprise, he not only consented to work with us, but developed a complete plan, and explicit technical details of how he would collaborate with us. He was not going to hand over any document to us - that he made clear beyond a doubt. But he was willing to meet me, provided that I knew shorthand, every second week and give me verbal reports on issues of interest." (35)

Over the next few months Massing and other NKVD agents worked to recruit Duggan. One report by Norman Borodin stated: "Our relations with Duggan continue being friendly. He would like very much to give us more urgent stuff, but asks us to recognize his more or less isolated position (in the State Department) with regard to the materials in which we are interested." (36) Duggan eventually passed very important documents to the Soviets. (37)

Boris Bazarov now told Hede Massing to concentrate on Noel Field. Massing wrote in This Deception: KBG Targets America (1951): "To 'develop' Noel Field was the task I was to concentrate on. I was to keep my eyes open, meet other people and report on whatever could be of value to us; but Noel was my main assignment.... I met them one evening at their own home. We hit it off extremely well. Not only was Herta Field from Germany, but the atmosphere, the whole household, was very similar to any intellectual German household that I had known. Herta and Noel were deeply concerned about fascism in Germany and were very well informed on all the political issues of importance. It was quite obvious that the first evening that Noel was a learned and astute student of Marxism." (38)

In April 1936 Massing's reported to her controller that Field had been recently approached by Alger Hiss just before he left to attend a conference in London: "Alger Hiss (she used his real name because she was unaware of his codename) let him know that he was a Communist, that he was connected with an organization working for the Soviet Union and that he knew Ernst (Field) also had connections but he was afraid they were not solid enough, and probably, his knowledge was being used in a wrong way. Then he directly proposed that Ernst give him an account of the London conference." The memorandum continued: "In the next couple of days, after having thought it over, Alger said that he no longer insisted on the report. But he wanted Ernst to talk to Larry and Helen (Duggan) about him and let them know who he was and give him (Alger Hiss) access to them. Ernst again mentioned that he had contacted Helen and Larry. However, Alger insisted that he talk to them again, which Ernst ended up doing. Ernst talked to Larry about Alger and, of course, about having told him 'about the current situation' and that 'their main task at the time was to defend the Soviet Union' and that 'they both needed to use their favorable positions to help in this respect.' Larry became upset and frightened, and announced that he needed some time before he would make that final step; he still hoped to do his normal job, he wanted to reorganize his department, try to achieve some results in that area, etc. Evidently, according to Ernst, he did not make any promises, nor did he encourage Alger in any sort of activity, but politely stepped back. Alger asked Ernst several other questions; for example, what kind of personality he had, and if Ernst would like to contact him. He also asked Ernst to help him to get to the State Department. Apparently, Ernst satisfied this request. When I pointed out to Ernst his terrible discipline and the danger he put himself into by connecting these three people, he did not seem to understand it." (39)

Boris Bazarov

On 26th April, 1936, Boris Bazarov reported back to Moscow: "The result has been that, in fact, Field and Hiss have been openly identified to Duggan. Apparently Duggan also understands clearly her (Hede Massing) nature... Helen Boyd (Duggan's wife), who was present at almost all of these meetings and conversations, is also undoubtedly briefed and now knows as much as Duggan himself... I think that after this story we should not speed up the cultivation of Duggan and his wife. Apparently, besides us, the persistent Hiss will continue his initiative in this direction. In a day or two, Duggan's wife will come to New York, where she (Hede Massing) will have a friendly meeting with her. At Field's departure from Washington, Helen expressed a great wish to meet her again. Perhaps Helen will tell her about her husband's feelings." (40)

Headquarters instructed Bazarov to be certain that none of his agents undertook similar meetings across jurisdictional boundaries without your knowledge". Bazarov was particularly concerned about the behaviour of Hede "knowing that her drawbacks include impetuousness". They made it very clear that they were very keen to recruit Laurence Duggan and his wife: "Therefore we believe it necessary to smooth over skillfully the present situation and to draw both of them away from Hiss... It is our fault, however, that Field, who is already our agent, has been left in her (Hede Massing) charge, a person who is unable to educate either an agent or even herself."

Allen Weinstein, the author of The Hunted Wood: Soviet Espionage in America (1999) that Hede Massing concentrated on recruiting New Deal officials. This included Alger Hiss. According to recently released document this upset her masters in Moscow: "We do not understand Gumperz's motives in having met with Hiss. As we understand, this occurred after our instruction that Hiss was (working with military intelligence) and that one should leave him alone. Such experiments may lead to undesirable results." Gumperz was described as being "impetuousness". (41)

Another Soviet agent, Itzhak Akhmerov, defended Hede Massing: "She (Massing) met with Hiss only once." He quotes, Joszef Peter (the man that Whittaker Chambers identified as a Soviet agent in his testimony before the House of Un-American Activities Committee on 3rd August, 1948) as saying: “You in Washington came across my guy (Hiss)… You better not lay your hands on him.” (42)

The NKVD was able to recruit Duggan. Massing reported back to Moscow in May 1936: "He (Duggan) said he preferred... being connected directly with us (he mentioned our country by name) because he could be more useful... and that the only thing which kept him at his hateful job in the State Department where he did not get out of his tuxedo for two weeks, every night attending a reception (he has almost 20 countries in his department), was the idea of being useful for our cause."

It was suggested that Duggan should be paid money for his information. Boris Bazarov reported back to Moscow: "You ask whether it is timely to switch him to a payment? Almost definitely he will reject money and probably even consider the money proposal as an insult. Some months ago Borodin wanted to give Duggan a present on his birthday. He purchased a beautiful crocodile toiletries case with (Duggan's) monograms, engraved. The latter categorically refused to take this present, stating that he was working for our common ideas and making it understood that he was not helping us for any material interest." (43)

Noel Field, was eventually recruited. He later recalled: "We (Noel and Herta Field) made friends with Alger Hiss – an official of the New Deal brought about by Roosevelt – and his wife. After a couple of meetings we mutually realized we were Communists. Around the summer of 1935 Alger Hiss tried to induce me to do service for the Soviets. I was indiscreet enough to tell him he had come too late. Naturally I didn't say a word about the Massings."

Hede Massing got on very well with Boris Bazarov: "Fred (Boris Bazarov) was a small man, shy and soft-spoken, partly bald and crowding fifty, unassuming and of good education. He was unobtrusive sort who would not draw a second look in a crowd, a valuable asset in his occupation. In Europe, during my frequent courier journeys, I heard that he came from an aristocratic family and had been an officer in the Tsar's army, but I could not confirm this... His wife was with him in New York. But in all our years of cordial relations I never met her nor did I know where they lived." (44) On one occasion he sent her fifty long-stemmed red roses. The note said: "Our lives are unnatural, but we must endure it for humanity. Though we cannot always express it, our little group is bound by love and consideration for one another. I think of you with great warmth."

Hede Massing also worked with Joszef Peter. Her former husband, Gerhart Eisler, had suggested that Peter was the man to obtained false passports for agents: "And so at an early breakfast in Childs restaurant on 23rd Street and Fifth Avenue and a few days later he introduced me to J. Peters, a dark, heavy-set Hungarian with a clipped mustache whom I had known until then only by reputation. He was amiable and soft-spoken.... It was the same Peters who was informed by Whittaker Chambers of my solicitation of Noel Field, the same Peters who had been informed by Chambers about my meeting with Hiss. But he gave no sign of his knowledge." (45)

Disillusioned with NKVD

By the summer of 1937, over forty intelligence agents serving abroad were summoned back to the Soviet Union. Walter Krivitsky realised that his life was in danger. Alexander Orlov, who was based in Spain, had a meeting with fellow NKVD officer, Theodore Maly, in Paris, who had just been recalled to the Soviet Union. He explained his concern as he had heard stories of other senior NKVD officers who had been recalled and then seemed to have disappeared. He feared being executed but after discussing the matter he decided to return and take up this offer of a post in the Foreign Department in Moscow. General Yan Berzin, Dmitri Bystrolyotov and Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko, were also recalled. Maly, Antonov-Ovseenko and Berzen were all executed. (46)

Ignaz Reiss became concerned that he would also be eliminated. Richard Deacon, the author of A History of the Russian Secret Service (1972) has pointed out: "Ignace Reiss suddenly realised that before long he, too, might well be next on the list for liquidation. He had been loyal to the Soviet Union, he had carried out all tasks assigned to him with efficiency and devotion, but, though not a Trotskyite, he was the friend of Trotskyites and opposed to the anti-Trotsky campaign. One by one he saw his friends compromised on some trumped-up charge, arrested and then either executed or allowed to disappear for ever. When Reiss returned to Europe he must already have known that he had little choice in future: either he must defect to safety, or he must carry on working until he himself was liquidated." (47)

In July 1937 Ignaz Reiss received a letter from Abram Slutsky and was warned that if he did not go back to Moscow at once he would be "treated as a traitor and punished accordingly". It was therefore decided to defect. Reiss wrote a series of letters that he gave in to the Soviet Embassy in Paris explaining his decision to break with the Soviet Union because he no longer supported the views of Stalin's counter-revolution and wanted to return to the freedom and teachings of Lenin. "Up to this moment I marched alongside you. Now I will not take another step. Our paths diverge! He who now keeps quiet becomes Stalin's accomplice, betrays the working class, betrays socialism. I have been fighting for socialism since my twentieth year. Now on the threshold of my fortieth I do not want to live off the favours of a Yezhov. I have sixteen years of illegal work behind me. That is not little, but I have enough strength left to begin everything all over again to save socialism. ... No, I cannot stand it any longer. I take my freedom of action. I return to Lenin, to his doctrine, to his acts." These letters were addressed to Joseph Stalin and Abram Slutsky. (48) Reiss also sent a copy to Hede Massing.

Allen Weinstein, the author of The Hunted Wood: Soviet Espionage in America (1999) has pointed out that both Hede and Paul Massing had worked for Reiss and that he had "been informed about various American agents of the NKVD... Protecting Soviet agents in the U.S. government as well as in Europe, therefore, required killing Ignatz Reiss before he denounced figures such as Duggan and Field." (49)

Murder of Ignace Reiss

Hede Massing informed Boris Bazarov that she was no longer willing to work for the NKVD. Bazarov arranged for Hede and Paul Massing to meet with his boss, Elizabeth Zarubina. Massing described her as having strange, beautiful eyes - large, and dark, heavy-browed, with long, curled eyelashes. They shone from a face of small, delicate features, dark skinned, and narrow of mouth. Her warm and engaging smile which she gave so sparingly, exposed large, beautiful teeth. The exquisite head belonged to a small, frail body. Her posture was poor, however, and she had large, painfully bad feet, and ugly hands. She was polite and completely self-assured. She had an authoritative air about her without being annoying or aggressive. Her English was flawless as was her German."

Zarubina explained to Massing that Reiss posed to the Soviet Union: "In case you have not been advised. Ludwig (Reiss) has betrayed us, he has gone over to the bourgeoisie, he is a Trotzkyite. You know that he was critical of the Soviet Union." Paul replied "He is not more critical than I am. He is no more a traitor than I am." Hede added: "He (Reiss) is not a traitor. He cannot be a traitor!" Zarubina responded by claiming that "Ludwig has joined the enemy, he ran away from us, he did not come home to discuss his doubts, to get contact again with the workers and the revolution. He left the service without permission. He is dangerous."

Massing, who heard about NKVD agents such as Theodore Maly, Yan Berzin, Dmitri Bystrolyotov and Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko, being recalled and murdered commented: "You don't make it very inviting for comrades to go home to discuss their doubts, as you put it, at a time when all the old friends and fighters are liquidated as enemies of the people. Trotzkyites, and Gestapo agents." Paul added: "A man of Ludwig's status within the organization does not have a chance to be let go - if a small and comparatively unimportant functionary like Hede could not be released easily?"

Zarubina eventually told them "Nobody here has the authority to release you. Hede. You know that. That can only be done at home (Moscow). A comrade who has problems goes home and faces his superiors and discusses his problems. He does not run away, like Ludwig!" (50)

Elizabeth Zarubina called another meeting with Paul Massing. She told him that Ignaz Reiss had been assassinated on 4th September, 1937. (51) Paul said to Hede: "Do you realize that Ludwig's death means immediate danger for us?" However, amazingly, they both agreed to visit Moscow to discuss the purging of Soviet agents. She later recalled: "That we ventured on this trip in spite of the fact we had heard that during the first five months of 1937, 350,000 political arrests had been made by the GPU, was fantastic as I look back on it." (52)

Moscow

Paul and Hede Massing sailed on the Kungsholm. "We had obtained a large and lovely stateroom. It was winter, and there were not many people on board. We decided to make the best of the situation and at least enjoy the trip on that beautiful ship. At the very first meal we spotted Helen (Elizabeth Zarubina). She had, of course, not told us that she would be on board with us. It was not a pleasant surprise. But there was little we could do except to maintain a relationship on good terms. It was a long trip that faced us and we would be together a long time." (53)

They arrived in Leningrad at the end of October, 1937. "Later that evening we walked through the streets of Leningrad. It was the end of October, 1937. Paul had not seen Russia since 1931, and I had been there last in 1933. Not a thing had changed. People looked sad, poorly dressed, impoverished, worried, miserable. Stores had poor goods, if any; streetcars were crowded, houses were dilapidated-slums on a large scale. The same potted palms that are to be seen in every Russian hotel; the same frightened, subservient waiters and chambermaids; the same smiling hotel director, who was, as always, an NKVD man." (54)

Paul and Hede Massing arrived in Moscow on 5th November, 1937. Two days later Elizabeth Zarubina introduced the couple to a man she called "Peter". He was in fact, Vassili Zarubin, her husband. "Helen (Zarubina) would sit quietly and simply elaborate once in a while upon a point that Paul or I had mentioned. She seemed matter of fact. Her relationship with Peter was businesslike, with a slight indication that he was a man of higher military rank than she. At some of my stories, especially my description of certain people, for example, when I dramatized Walter's drunken escapades or Bill's bureaucratic pettiness, Peter roared with laughter. He never restrained me in my critical attitude toward some of my Russian co-workers. He never seemed to think as highly as I did, however, of Fred or Ludwig. That did not deter me from speaking of Ludwig as I always had - with admiration and devotion. When it came to the issue of Ludwig, his whole attitude changed. He would be extremely eager to draw every possible bit of information from me." (55)

In January 1938 they were interrogated by Mikhail Shpiegelglass. "Peter (Vassilli Zarubin) brought a man with him one night whom we both liked very much. He seemed as European as Peter was Russian: cultured, civilized, pleasant. He spoke German almost fluently, with a slight eastern intonation that reminded me of Ludwig and Felik; and made me feel at home with him. They had come many hours later than they had announced themselves, and I accordingly was set to be as cross as possible... His manner had a way of putting one on the defensive. He shook hands heartily and said, 'I am Comrade Spiegelglass.' Somehow we knew that this was his real name, the significance of which we learned many years later when Krivitsky's book was published. This charming comrade was responsible for the murder of Ludwig! (Ignaz Reiss). In keeping with routine procedure, he must have earned a medal for it. Obviously, he had come into the last phase of our initial interrogation and wanted a few points elaborated upon. It was as though it was his job to pull in all the loose strings and weave them tightly, securely, together. After he had finished with us we were taken into the social and family life of the NKVD. Their purpose in doing this was to express their gratitude, their esteem and trust of us." (56)

Hede Massing asked Vassili Zarubin if they could have an exit visa so that they could leave the Soviet Union. He said that he did not have the authority to do that. A few days later he arranged a meeting with Nikolai Yezhov, the head of the NKVD. Zarubin warned her: "Hede, be careful when you talk to this man; don't tell him what you said to me, but tell him that you want to go out-and don't stress the point that you want to leave our service. He knows that. He is very important."

"The meeting took place in the Sloutski apartment, the same one where I had been at our first party. When we arrived, the important man was not yet there. There was an atmosphere of expectation. There was no vodka, as was usual before meetings. We sat and waited. There was not even flippant conversation. Finally he arrived. He, too, was in uniform. Though he had little glitter, still it was obvious that he was of a higher rank than my two companions. He was a man of about thirty-five, a Georgian, and fairly good looking in a foreign kind of way; to me, from the very first second, he was despicable. He took a seat on the other side of the room from me, crossed his legs, pulled out a heavy gold tabatiere, slowly tapped a cigarette on it - scrutinizing me throughout the process. Then he said in Russian what amounted to, Let her talk."

Zarubin told Hede Massing, "Tell your story, and I will interpret." Hede was so angry by Yezhov's attitude that she replied: "There is no story to tell. I'm tired of my story. I understood that I was brought here to ask this gentleman for my exit visa. All I am concerned with at this point is that my husband and I be able to leave for home. I've told my story time and again; I am sure that Mr. X can have access to it. So all I have to say now is - when am I going to leave?" Yezhov laughed out loud. "It infuriated me! I mimicked his laugh and said, 'It is not that funny, is it? I mean what I say!' He got up, said in Russian that the conference was ended, and without a word or a nod toward me, he left." (57)

Hede and Paul Massing appeared to have no chance now of getting an exit visa. Boris Bazarov, who was back in Moscow, was unable to help. Soon afterwards they met Noel Field who was also visiting the country. She decided to use this opportunity to get out of the Soviet Union. She telephoned Bazarov and told him: "When I had been connected and heard his answer at the other end of the wire, I said in a loud and clear voice, 'Boris, I have been asking you for our exit visas long enough! We have guests, Herta and Noel Field. I want them to be witness to my request. I am asking you for our exit visas for the last time... I should like to have our passports with the visas today. If we do not get them today, I shall have to make use of my rights as an American citizen. I will then go with my friends, the Fields, to the American Legation to ask for help.' I hung up. I was shaking."

Several hours later there was a knock on the door. It was Bazarov and in his hand he held a large envelope. "Here are your passports and the visas and a slip for Intourist, with which you can pick up your tickets tomorrow morning. We have made reservations for you on the evening train, via Leningrad." Hede Massing later recalled: "No further comment. He left. I held the envelope out to Paul. All strength had left me, I could not have opened it. It was true. It was really true. We could leave!" (58) Soon afterwards Bazarov was executed.

The Second World War

On their return to America, Hede and Paul Massing purchased Courtney Farm in Haycock Township in Bucks County and ran it as a paying guest farm. "I thought of it as a great priviledge; I developed a pride in our possessions, a knack for the paying-guest business. Our earnings were modest but sufficient to let me start collecting ironstone and old glass and some good pieces of furniture. Life was pleasant. We had a good library, music, evenings in front of the fireplace, discussions with people we liked (we did not take any others). (59)

In 1942 Paul Massing began working at the Institute of Social Research at Columbia University in New York City. In August he notified NKVD that his friend, Franz Neumann, had recently joined the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). Massing reported to Moscow that Neumann had told him that he had produced a study of the Soviet economy for the OSS's Russian Department. (60) In April 1943, Elizabeth Zarubina, a Soviet spy in the United States, and the wife of Vassily Zarubin, met with Neumann: "(Zarubina) met for the first time with (Neumann) who promised to pass us all the data coming through his hands. According to (Neumann), he is getting many copies of reports from American ambassadors... and has access to materials referring to Germany."

Neumann promised to cooperate fully during his initial meeting with Zarubina, after becoming a naturalized American citizen later that year he appeared to become reluctant to pass secret information. One memorandum sent to Moscow in early January 1944 described a conversation between Neumann and his friends Paul and Hede Massing, in which they "directly asked him about the reasons for his ability to work" and tried to determine whether he had changed his mind. Neumann responded: "I did not change my mind. If there is something really important, I will inform you without hesitation." (61)

Gerhart Eisler and the HUAC

Gerhart Eisler appeared before the House of Un-American Activities Committee on 6th February, 1947. He was accompanied by his attorney Carol Weiss King and a "phalanx of reporters". J. Parnell Thomas, the chairman of the HUAC stated: "Mr. Gerhart Eisler, take the stand." Eisler replied: "That is where you are mistaken. I have to do nothing. A political prisoner has to do nothing." Walter Goodman, the author of The Committee: The Extraordinary Career of the House Committee on Un-American Activities (1964), commented: "He (Eisler) and Thomas yelled at one another for a quarter of an hour without getting anywhere. He was cited for contempt on the spot, and escorted back to his cell on Ellis Island." (62)

FBI agent Robert J. Lamphere was put in charge of the case. He decided that it would be important to interview Eisler's former wife and her husband. According to their records both of them had a left-wing background. First of all he interviewed Paul Massing. Lamphere later recalled: "An economist at a social research institute, Paul was distinguished, erect and completely uncooperative. He believed that the FBI had kept him from becoming a citizen by giving derogatory information on him to the Immigration and Naturalization Service. Actually, Paul was right about that, but when the interview was drawing to a close and he had told us nothing of value, this talk of citizenship made me a bit hot under the collar. Standing to leave, I said with some vehemence that becoming a citizen was a privilege, not a right, and that Paul had lived safe and secure in the United States during the war, whereas if he'd stayed in Germany the Nazis would long since have killed him." (63)

Paul talked to Hede about this experience: "Paul and I thought the problem out, slowly, carefully. We decided to tell our story. Two polite efficient men asked me for some specific information regarding Gerhart Eisler. They not only understood and respected my rights, but made it clear that my co-operation was purely voluntary. There was no coercion, no tricks; they had a job to do and they thought that I could be of help if I cared to. It was entirely up to me whether I did. They were intelligent, observant, well-informed - as I could judge by the questions asked - and pleasantly unemotional. They did not underestimate the individual under suspicion, on the contrary, they seemed to respect him and understand him in his own environment. This impressed me indeed. It was most unexpected. The two agents, to whom I spoke the first few times, were Lamphere and a kindly, graying, middle-aged man, whose name was Hugh Finzel." (64)

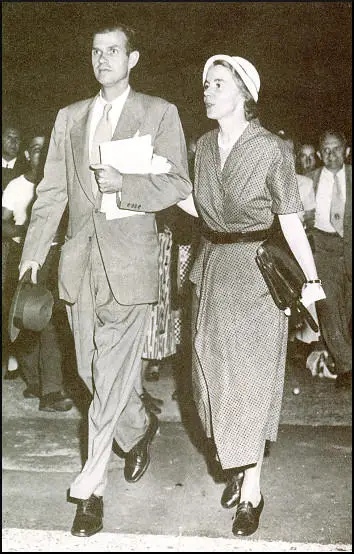

Robert J. Lamphere later wrote about his impressions of Hede Massing in his book, The FBI-KGB War (1986): "A tall, middle-aged, carefully dressed woman, no longer the striking beauty she had obviously been in her youth, Hede was still attractive... Languishing in Berlin, Hede had dinner with Richard Sorge, who later became one of the most successful Communist spies of the era. Sorge, formerly a Comintern man like Gerhart, had spirited his wife away from an older man, just as Paul had taken Hede from Julian. At dinner he convinced Hede that espionage was heroic and glamorous and that she, too, could do important things for the Party. He took her to meet 'Ludwig,' a man she discovered she already knew as a regular customer of the Gumperz bookstore, where she had worked for a time. Ludwig... was sometimes known as Ignace Reiss, a charming, erudite man who inspired near-fanatic loyalty on the part of Hede and many other agents. Together with his childhood friend Walter Krivitsky, Ludwig was a mainstay of Russian intelligence and had been so since the early 1920s. On his instructions Hede dropped her attendance at local Party meetings, provided details and evaluations of promising prospects, located 'safe' apartments for agents and set up 'mail drops' where messages could be exchanged - in short, she learned the rudiments of courier work." (65)

Massing told Lamphere that she joined a spy network that included Vassili Zarubin, Boris Bazarov, Elizabeth Zarubina, Joszef Peter, Earl Browder and Noel Field. However, she decided not to tell the FBI about Laurence Duggan and Alger Hiss. "The two most important names I did not mention in my confidential sessions with the FBI were Larry Duggan and Alger Hiss.... I was absolutely convinced that Duggan had left the organization, if, indeed, he had ever belonged to it at all. Alger Hiss had not worked with me, the relationship was a fleeting one, important only in connection with Noel Field. But more than that, he, too, I was convinced, must have broken with whatever his organization might have been. I had watched his career with great interest." (66)

On 3rd August, 1948, Whittaker Chambers appeared before the House of Un-American Activities Committee. He testified that he had been "a member of the Communist Party and a paid functionary of that party" but left after the signing of the Nazi-Soviet Pact in August 1939. He explained how the Ware Group's "original purpose" was "not primarily espionage," but "the Communist infiltration of the American government." Chambers claimed his network of spies included Alger Hiss, Harry Dexter White, Lauchlin Currie, Abraham George Silverman, John Abt, Lee Pressman, Nathan Witt, Henry H. Collins and Donald Hiss. (67)

Hede Massing wrote: "On the morning of August 3, 1949, when the Hiss-Chambers story broke, my worries began. Had I been all wrong in my rationizations? No, I couldn't have been... The Hiss-Chambers story unfolded. Every one of Chambers' statements sounded a familiar note. Though I had never met Whittaker Chambers, I knew a great deal about him. I remembered how enthusiastic American party member friends were about him, and about his intelligence, his courage, and his loyalty to the Party. I grew exceedingly uneasy... I was very much concerned. I did know about Hiss. Was it my duty to tell." (68)

Trial of Gerhart Eisler

The trial of Gerhart Eisler opened in July 1947. Louis Budenz once again told of Eisler's inflammatory activities in the 1930s and 1940s. Hede Massing and Eisler's sister, Ruth Fischer testified about his long history as a Communist and Comintern man. Helen R. Bryan, executive secretary of the Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee (JAFRC), admitted that she had paid Eisler a monthly sum of $150, under the name of Julius Eisman. The FBI also provided information on the false passports that Eisler used in the 1930s. During this evidence Eisler's lawyer, Carol Weiss King, pointed at Robert Lamphere and shouted, "This is all a frame-up by you." (69)

Louis Budenz told the HUAC that Eisler's role in the Communist Party of the United States was to lay down Comintern discipline to "straying functionaries". However, the most powerful evidence against Eisler came from his sister, Ruth Fischer. She described her brother as "the perfect terrorist type". Fischer had not been on speaking terms with her brother since she was expelled from the German Communist Party (KPD) in 1926 after attacking the policies of Joseph Stalin. (70) She told the HUAC that Eisler had carried out purges in China in 1930 and had been involved in the deaths of numerous comrades, including Nikolay Bukharin. (71)

Time Magazine reported: "One of the witnesses who denounced him was his sister, sharp-chinned, black-haired ex-German Communist Ruth Fischer, the person who hates him most. In the beginning, as children of a poverty-stricken Viennese scholar, they had adored each other. Ruth, the older, became a Communist first. Gerhart, who won five decorations as an officer of the Austrian Army in World War I, joined the party in the fevered days of 1918. They worked together. When Ruth, then a bundle of sex appeal and intellectual fire, went to Berlin, Gerhart followed. She became a leader of the German Communist Party, and a member of the Reichstag. But Gerhart took a different ideological tack, began to covet power for himself. He applauded when Ruth was banished from the party by the Stalinist clique." (72)

On 9th August, 1947, Gerhart Eisler "took the stand, dressed in his shapeless gray suit and blue shirt with its too-large collar." (73) Eisler argued: "I never in my life was a member of the Communist International. I never in my life went anyplace in the whole world as a representative of the Comintern." (74) Eisler denied he was a member of a group that advocated the overthrow of the United States government. He was a member of the German Communist Party (KPD) and this was not one of its policies. After only a few hours of deliberation, the jury brought in a guilty verdict and he was sentenced to a year in prison.

Alger Hiss Perjury Trial

On 15th December, 1948, the grand jury asked Alger Hiss whether he had known Whittaker Chambers after 1936, and whether he had passed copies of any stolen government documents to Chambers. As he had done previously, Hiss answered no to both questions. The grand jury then indicted him on two counts of perjury. The New York Times reported that he "appeared solemn, anxious, and unhappy" with a grim and worried look". It added that to "observers it seemed obvious that he had not expected to be indicted".

The trial began in May 1949. The first piece of evidence concerned a car purchased by Chambers for $486.75 from a Randallstown car dealer on 23rd November, 1937. Chambers claimed that Hiss had given him $400 to buy the car. The prosecution was able to show that on 19th November Hiss had withdrawn $400 from his bank account. Hiss claimed that this was to buy furniture for a new house. But the Hisses had not signed a lease on any house at that time, and could produce no receipts for the furniture.

The main evidence that the prosecution produced consisted of sixty-five pages of re-typed State Department documents, plus four notes in Hiss's handwriting summarizing the contents of State Department cables. Chambers claimed Alger Hiss had given them to him in 1938 and that Priscilla Hiss had retyped them on the Hisses' Woodstock typewriter. Hiss initially denied writing the note, but experts confirmed it was his handwriting. The FBI was also able to show that the documents had been typed on Hiss's typewriter.

In the first trial Thomas Murphy stated that if the jury did not believe Chambers, the government had no case, and, at the end, four jurors remained unconvinced that Chambers had been telling the truth about how he had obtained the typed copies of documents. They thought that somehow Chambers had gained access to Hiss's typewriter and copied the documents. The first trial ended with the jury unable to reach a verdict.

The second trial began in November 1949. Hede Massing was now one of the main witnesses against Alger Hiss. She claimed that at a dinner party in 1935 Hiss told her that he was attempting to recruit Noel Field, then an employee of the State Department, to his spy network. Whittaker Chambers claims in Witness (1952) that this was vital information against Hiss: "At the second Hiss trial, Hede Massing testified how Noel Field arranged a supper at his house, where Alger Hiss and she could meet and discuss which of them was to enlist him. Noel Field went to Hede Massing. But the Hisses continued to see Noel Field socially until he left the State Department to accept a position with the League of Nations at Geneva, Switzerland-a post that served him as a 'cover' for his underground work until he found an even better one as dispenser of Unitarian relief abroad. (75)

Hede Massing published a book on her spying activities, This Deception: KBG Targets America in 1951. Morris L. Ernst wrote on its publication: "This is the moving and extraordinary story of a woman's life... I imagine she is one of the few Communists who was sent for to go to Moscow to be purged and nevertheless got out alive.... By some it will be read as an absorbing and touching love story. To others it will take on the cloaks and daggers of a thriller, although its pace is quieter and subtler than one might expect. It is an important book as well as a readable one; in many ways it is typical of the life of a European Communist and, moreover, it explicity touches on a very sensitive spot in the culture of our own nation. Why do people join the Communist party? What, then, impels them to renounce it? Above all, what is our attitude toward encouraging them to leave the Communist party? (76)

Confession of Noel Field

Noel Field was arrested on the orders of Lavrenti Beria. It was claimed that he had been spying on behalf the United States. Field was tortured and held in solitary confinement for five years. In East Germany, in August 1950, six members of the Communist Party were arrested and accused of "special connections with Noel Field, the American spy." Field was also named as a spy in the trial of Rudolf Slansky, the Secretary General of the Communist Party, and 13 other officials. Slansky was executed on 2nd December, 1952.

While in prison he claimed that like him, Alger Hiss had been a Soviet spy during the 1930s. According to Major Szendy of the Hungarian Interior Ministry: "Field confessed … only now recognizing that he had become a tool for the American intelligence and that he had also handed over other people to the American intelligence. Field emphasized repeatedly, that decades ago, while he was in the USA, he had approached the Communist Party and had cooperated with the Soviet intelligence agencies for a long period of time; he did not know why this connection was cut off. Furthermore, he emphasized that the House Committee on Un-American Activities was investigating him in connection with the case of Alger Hiss. Field stated that he had been trying to clarify his membership in the Communist Party since 1938 (when he travelled to Moscow) and that he was promised, last time in Poland, that this would happen." Noel Field admitted that he had been recruited by Hede Massing in 1934: "In the year 1934 (as far as I remember) I got in touch with the German communists Paul Massing and Hede Gumpertz who informed me that they were spying for the Soviet Union. I handed over lots of information to them – orally as well as in writing - about the State Department." (77)

Hede Massing died on 8th March, 1981. Robert J. Lamphere pointed out "she passed away, at age eighty-one, and I was annoyed to note that the New York Times, which claims to be both accurate and the newspaper of record, printed, instead of a photograph of Hede, a 1949 photo of Brunhilda Eisler, Gerhart's third wife." (78)

Primary Sources

(1) Hede Massing, This Deception: KBG Targets America (1951)

My parents, so occupied with their own problems, never paid much attention to any of my successes or failures in school. I never could discuss anything with mother. My brother Walter, born when I was seven years old, shortly after we had come back from America, was too young to be a companion or even to talk to. And still I do not remember any intense friendships with girls of my class which would have seemed natural for a lonely child like me. It must have been about the last year of Burgerschule that I met Ida Ehre and was accepted by her family. Mrs. Ehre, a charming, handsome woman of culture with a great love for music, was the first person I told of my unhappy home life; of my father's weakness for gambling and women, and of my mother's helplessness. It was at the Ehres' where I first spent simple, gay evenings, where I learned to listen to music. This was the sort of family that I longed for, kindhearted, generous, interested in the arts, and particularly in music. It was to become my real home for some time.

This was 1914, my last year in high school and the time to decide whether I was to go on with school or learn a trade.

At this time it was the fad to send girls to Hohere Tdchterschule, precollege schools where they learned homemaking and the appreciation of the fine arts. Very few girls went to college during those years. A business school would have been more appropriate for my economic status. My parents wanted me to learn a trade since my mother thought that I would marry very quickly, so why spend the time and the money, of which she had very little by then, to continue school?I have always been sensitive about my lack of formal education. I find it very difficult to reconstruct my feelings at that time. As nearly as I remember, I was most eager to continue school and to learn. I had come to love to read, and had even started my own modest library. But there was nothing I could do to convince my family and so I started as an apprentice in a small millinery shop in the fashionable section of town.

That was just a few months after the beginning of World War I. This did not affect us immediately, except that my father was drafted. That was a good day in my life! Not only was he not around any more, but he gave me a chance to be proud of him. Any girl of fifteen is proud to have a father in the armed forces; and he had indeed given me little chance to be proud of him before that. Hard as it was to live without any warmth or attention from my mother, it was nothing compared to the agony and shame my father's escapades caused me. I learned in later years, however, to forget the painful incidents and to remember the amusing ones.

(2) Hede Massing, This Deception: KBG Targets America (1951)

My father was a handsome man. I inherited from him only his height, his reddish curly hair, and, alas!, probably some of his less attractive character traits. Whenever I have become aware of them, I have tried to tear them out of me. Long after I had left home, my sister Elli once remarked that I danced like Papa. I stopped dancing for years. I still become tense when my brother tells me that I walk or smile "just like Papa." He is, to me, the personification of flightiness, instability, and insecurity. It is in reaction to him that I have never in my life gambled in any form whatsoever, that I do not know how to play cards or any other competitive game. To be thought "as charming as your father" used to make me wild with panic. My Polish father, seemingly an adaptable man, had easily acquired all the virtues accredited to the "Viennese." Dancing, singing, speaking several languages (though he never spent a minute studying them), gambling and the other things which would not be nice for a daughter to say; in these things he was most adept. And so, in reaction to him, I am not and do not want ever to be thought a "charming Viennese." He left my mother shortly before the end of the first world war. I have not heard from him since.

(3) Hede Massing, This Deception: KBG Targets America (1951)

My apprenticeship in the millinery shop proved to be a complete failure. I was again, as I had been in school and as was going to be ever so often in life, quite out of place. I did not like hats (I still have the aversion), and I did not like the girls in the shop. And I am sure that they did not like me. They thought me pretentious and stand-offish.

That summer I met a young law student at the Gaensehaufel, a public bathing place on the Danube. He took me to some lectures by Karl Kraus. At that time Karl Kraus seemed to a number of us young people the most influential and outstanding thinker and writer of Vienna. He was editor and publisher of the magazine, Die Fackel, or The Torch, and had great influence in forming the attitude and thinking of my generation. His most effective medium was satire, but he was a fine poet and dramatist. He was also a superb actor. During his performances (one could not call them lectures), which were held regularly in the Kleinen Konzerthaussaal, a small, graceful auditorium, he read, or better, dramatized the Austrian classics. One of his favorites, and also mine, was Nestroy, whom he interpreted as I have never heard it before or since. But his greatest hold on young people was his biting, hard-hitting criticism of society, his championship of the poor, his mockery of dishonest journalism. He was sharp, witty and kind at the same time.

A small man, slightly hunchbacked, he had a fine, aristocratic head and expressive hands which he used with a great flair in his dramatic performances. He was the father of most of the great contemporary Austrian writers and poets of the time, printing their first works in his magazine, helping them in many ways.It was natural for him to be a pacifist during the war. His magazine was verboten for some time. The few meetings he held during the war were memorable dramatic demonstrations against it. Although he was definitely against communism, he can be considered a forerunner and molder of many of the young people who later joined the Communist party. I am grateful to him for all the interests he wakened in me. To him, and to Victor Stadler, the young lawyer, who first introduced me to Karl Kraus, I owe my thanks for my love of chamber music, for Bach, Beethoven and Haydn, for Heine, Balzac, and Stendhal.

Karl Kraus died July 17, 1936. The girls in the modiste shop had never heard Karl Kraus and did not want to listen to my praise of him. And since I still did not like hats, we were really rather unhappy together.

(4) Hede Massing, This Deception: KBG Targets America (1951)

I fell into the Bohemian life of the Vienna cafes with great ease. And I had soon chosen the Café Herrenhof as my headquarters, so to speak. I had acquired a stammtisch and I could order on the cuff, which for one of my financial status was of great importance. Yet it had even a more important significance; it meant that one was recognized as trustworthy even by the waiters in the Café Herrenhof, who were of a very suspicious species. In short, I had begun to be an individual, away from the realm of my family.

This whole setup, the conservatory and life in Café Herrenhof with no family to supervise me, was partly a war phenomenon and not entirely my own doing. I also acquired a circle of admiring young men. And though there was quite a turnover among them, I usually managed to keep three or four believing at the same time that I was in love with them. My hectic compulsion to be recognized as a lovable person, to be reassured continuously that though my family did not love me, there were others who did, was being generously helped along.