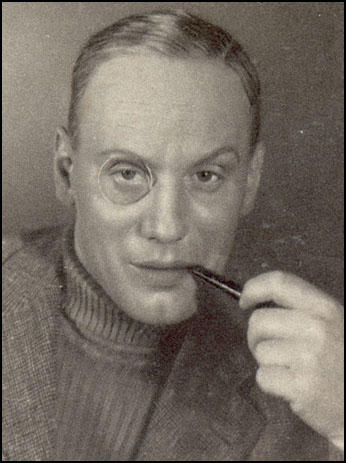

Gustaf Gründgens

Gustaf Gründgens, the son of a prosperous businessman, was born in Düsseldorf on 22nd December 1899. He served in the German Army during the First World War. After demobilization Gründgens attended acting school. According to Stefan Steinberg: "As a young man Gründgens was determined to make a name for himself. At 18 he sent a postcard to a friend advising the latter to hold on to the item because one day he, Gründgens, would be famous and the card would be valuable". (1)

Gustaf Gründgens formed an experimental theater troupe, the Laienbund Deutscher Mimiker. Other members included Klaus Mann, Erika Mann, and Pamela Wedekind, the daughter of the playwright Frank Wedekind. In 1924 Klaus wrote Anja and Esther, a play about "a neurotic quartet of four boys and girls" who "were madly in love with each other".

Gründgens decided to direct the play with himself in one of the male roles, Klaus in the other; Erika and Pamela Wedekind would be the two young women. "Klaus planned to marry Pamela, with whom Erika fell in love, while Erika arranged to marry Gustaf, with whom Klaus began an affair." (2)

Gustaf Gründgens and Erika Mann

The play, which opened in Hamburg in October 1925, attracted vast amounts of publicity, partly because of its scandalous content and partly because it starred three children of two famous writers. A photograph appeared on the cover of Berliner Illustrierte Zeitung. It created a great deal of controversy as "Klaus's lipstick gave him the look of a transvestite". (3)

Gustaf Gründgens, Erika Mann, Pamela Wedekind, and Klaus Mann (1925)

On 24th July, 1926, Gustaf Gründgens, married Erika Mann, even though both were gay. (4) The marriage was not successful and in 1927, she and Klaus traveled around the world. (5) Andrea Weiss, the author of In the Shadow of the Magic Mountain: The Erika and Klaus Mann Story (2008) has explained why the marriage failed: "A cynical explanation would point out that Erika’s theatrical career had flourished to the point where she no longer needed Gustaf as stepping-stone; that Gustaf had finally realised his marriage to Erika would not bestow on him her father’s impeccable social credentials." (6)

During this period Gründgens, like Erika and Klaus, were left-wing activists, and associated with members of the German Communist Party (KPD). In 1926 he talked about creating a "Revolutionary Theatre" and Klaus claims that he was "always ready to exchange a clenched-fist welcome on his way to rehearsals". At the same time Gründgens did not hide his abhorrence for Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party. (7)

Gründgens went to work for Germany's most prominent director Max Reinhardt. In 1932 he had his first opportunity to play the role with which he was to become closely identified - Mephistopheles in Goethe's Faust. Later that year he voted for the Social Democratic Party (SDP) and was known "to help gay friends, colleagues and left Jewish acquaintances". (8)

Nazi Germany

Gründgens was out of the country when Adolf Hitler came to power in early 1933. As his biographer has pointed out: "We have no way of knowing what went through his head. We do know that he was apprehensive about returning to Germany. He had not, after all, made his feelings about the Nazis a secret and he was wise enough to know that he could also encounter problems as someone, despite his short-lived marriage, known to be a homosexual." (9)

Gründgens did go back and he received the patronage of Hermann Göring. He was appointed the artistic director of the Prussian State Theatre and was later became a member of the Prussian state council. He was also director of Berlin's principal theatre, the Staatstheater. In 1934, his lawyer, a member of the Sturmabteilung (SA), arranged for Gründgens to move into a luxurious villa owned by a Jewish banker who had fled the country. Erika Mann, his former wife, suggested that Hitler had treated Gründgens well because of his sexuality: "Hitler's interest in him is interpreted as erotic." (10)

Gustaf Gründgens meeting Joseph Goebbels (1936)

Joseph Goebbels was openly hostile to him, as he was to all homosexuals (whom he referred to as 175ers according to the appropriate clause of the Weimar Constitution), but Gründgens was protected by Hitler and Göring. In 1936 Gründgens sealed a deal securing an annual average income of Reichsmark 200,000. Gründgens also starred in several propaganda films during this period earning on average RM80,000 per picture. In comparison a state secretary in Nazi Germany earned on average RM20,000. One critic claimed that "Gründgens is emblematic of the intellectual who chooses ego and career, even in the service of monsters, over principle." (11)

Gründgens's wife, Erika Mann, like many on the left, had been forced to flee Nazi Germany. So had his brother-in-law, Klaus Mann, who was living in Amsterdam. Klaus wrote to his mother that his publisher, Fritz Helmut Landshoff, had made him a "relatively generous offer", where he was to receive a monthly wage to write a novel. (12) Klaus originally intended to write a utopian novel about Europe in the 22nd century. The author Hermann Kesten suggested that he write a novel about a homosexual who is willing to compromise his ideals in order to have a successful career under Hitler. (13)

Klaus accepted his advice and based his novel on Gustaf Gründgens. (14) The novel, Mephisto (1936), portrays an actor Hendrik Höfgen (Gustaf Gründgens), who in his youth was a communist. However, unlike, Gründgens, he is not homosexual as Klaus was himself gay. He decided to use "negroid masochism" as the main character's sexual preference. In 1933, when Hitler gains power, he flees to Paris, because he expects to be persecuted for his left-wing activities. However, he is persuaded to return to Germany and takes the role of Mephisto. There are situations where Höfgen tries to help his friends or to complain about concentration camps, but he is always concerned not to lose his Nazi patrons. (15)

Post-War

In September,1944 Goebbels issued an order closing all German theatres until the end of the war. All available artistic personal were assigned to vital war production. However, Gründgens was allowed to sit out the rest of the war in his Berlin home. In April 1945 he was captured by the Red Army but eventually he was released and allowed to use his theatre talents in East Germany. In 1946 he managed to move to West Germany and over the next few years established himself as the best known actor-director in the country. (16)

Gustaf Gründgens

Klaus Mann, who was now living in Los Angeles, attempted to get Mephisto published in Germany. In April, 1949, he received a letter from his publisher to say that his novel could not be published in the country because of the objections of Gustaf Gründgens. (17) Klaus wrote to Erika Mann about his problems with his publisher and his financial difficulties. "I have been luck with my family. One cannot be entirely lonely if one belongs to something and is part of it." (18) Klaus Mann died in of an overdose of sleeping pills on 21st May 1949. (19)

Gustaf Gründgens remained in great demand as an actor-director until he died of an an overdose of sleeping tablets while on holiday in Manila on 7th October, 1963. (20)

Primary Sources

(1) Colm Tóibín, London Review of Books (6th November, 2006)

At the end of 1924, Klaus Mann wrote Anja and Esther, a play about "a neurotic quartet of four boys and girls" who "were madly in love with each other". The following year he was approached by the actor Gustaf Gründgens, who wanted to direct the play with himself in one of the male roles, Klaus in the other; Erika Mann and Pamela Wedekind, the daughter of the playwright Frank Wedekind, would be the two young women. The ambitious Gründgens, who was born in 1899, had a reputation in Hamburg but not in Berlin. At one point, as they worked on the play, Klaus planned to marry Pamela, with whom Erika fell in love, while Erika arranged to marry Gustaf, with whom Klaus began an affair. At Erika and Gustaf’s wedding reception, Erika noted that her mother’s brother was, as she wrote to Pamela, "flirting with Gustaf". The honeymoon was spent in a hotel where Erika and Pamela had stayed not long before as man and wife (Pamela had checked in dressed as a man).

Anja and Esther, which opened in Hamburg in October 1925, attracted vast amounts of publicity, partly because of its scandalous content and partly because it starred three children of two famous writers. One magazine put them on the cover, cropping out Gründgens’s face, making a point of his status as outsider amid all this fame. His marriage to Erika ended soon after it began. "A cynical explanation," Weiss writes, "would point out that Erika’s theatrical career had flourished to the point where she no longer needed Gustaf as stepping-stone; that Gustaf had finally realised his marriage to Erika would not bestow on him her father’s impeccable social credentials."

Pamela Wedekind married a man old enough to be her father, and the foursome returned to being the twosome of Erika and Klaus Mann. Although Erika played the part of Queen Elisabeth in Schiller’s Don Carlos at the State Theatre in Munich, she longed for greater excitement. And since Klaus was bored and his next play a flop, they decided to go to America, where they were ready to have their genius fully recognised. To amuse themselves, they told the US press that they were twins and thus began the American myth of The Literary Mann Twins. They went on a tour of the country. "Whenever they were stuck for funds," Weiss writes, "Klaus would write articles and Erika would write letters to organisations, seeking lecture engagements. They often arrived in town with no change in their pockets." Soon, they decided to tour the world. They stayed at the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo for more than six weeks – ‘kept in that luxurious prison by the evil spell of our unpaid bill’ – and, on being rescued by their father’s publisher, agreed to write a book about their travels as a way of paying him back.

Student Activities

Adolf Hitler's Early Life (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler and the First World War (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler and the German Workers' Party (Answer Commentary)

Sturmabteilung (SA) (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler and the Beer Hall Putsch (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler the Orator (Answer Commentary)

An Assessment of the Nazi-Soviet Pact (Answer Commentary)

British Newspapers and Adolf Hitler (Answer Commentary)

Lord Rothermere, Daily Mail and Adolf Hitler (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler v John Heartfield (Answer Commentary)

The Hitler Youth (Answer Commentary)

German League of Girls (Answer Commentary)

Night of the Long Knives (Answer Commentary)

The Political Development of Sophie Scholl (Answer Commentary)

The White Rose Anti-Nazi Group (Answer Commentary)

Kristallnacht (Answer Commentary)

Heinrich Himmler and the SS (Answer Commentary)

Trade Unions in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)

Hitler's Volkswagen (The People's Car) (Answer Commentary)

Women in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)

References

(1) Stefan Steinberg, The Rehabilitation of Gustav Gründgens (29th December 1999)

(2) Colm Tóibín, London Review of Books (6th November, 2006)

(3) Anthony Heilbut, Thomas Mann: Eros and Literature (1995) page 437

(4) Britta Probol, Norddeutscher Rundfunk (10th July, 2013)

(5) Time Magazine (10th October, 1938)

(6) Andrea Weiss, In the Shadow of the Magic Mountain: The Erika and Klaus Mann Story (2008) page 55

(7) Stefan Steinberg, The Rehabilitation of Gustav Gründgens (29th December 1999)

(8) Jacques Schuster, Die Welt (18th February, 2013)

(9) Stefan Steinberg, The Rehabilitation of Gustav Gründgens (29th December 1999)

(10) Anthony Heilbut, Thomas Mann: Eros and Literature (1995) page 529

(11) Stefan Steinberg, The Rehabilitation of Gustav Gründgens (29th December 1999)

(12) Klaus Mann, letter to Katia Mann (21st July 1935)

(13) Andrea Weiss, In the Shadow of the Magic Mountain: The Erika and Klaus Mann Story (2008) page 126

(14) Stefan Steinberg, The Rehabilitation of Gustav Gründgens (29th December 1999)

(15) Andrea Weiss, In the Shadow of the Magic Mountain: The Erika and Klaus Mann Story (2008) page 126

(16) Stefan Steinberg, The Rehabilitation of Gustav Gründgens (29th December 1999)

(17) Colm Tóibín, London Review of Books (6th November, 2006)

(18) Klaus Mann, letter to Erika Mann (20th May, 1949)

(19) Andrea Weiss, In the Shadow of the Magic Mountain: The Erika and Klaus Mann Story (2008) page 239

(20) Stefan Steinberg, The Rehabilitation of Gustav Gründgens (29th December 1999)