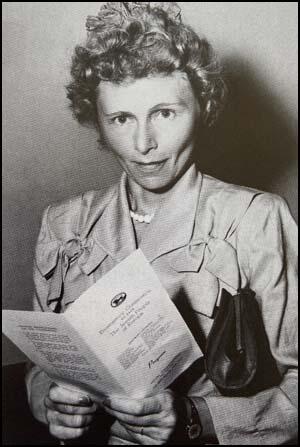

Frances Fineman

Frances Fineman, the second daughter of Dennis Fineman, a shopkeeper, and Sonia Fineman, was born on 13th September 1897. Her mother Sonia Fineman, fearing the date to be unlucky, insisted that her father register the birth three days later. An older brother, Bernard, had been born in 1896. (1)

Sonia, a blonde haired, blue-eyed Jew, had escaped from persecution from Russia and soon after arriving in New York City married her first husband. Although she was practically illiterate, she was a successful businesswoman. In her fabric store on Second Avenue, Sonia Fineman, sold the finest silks and velvets. Her father sold cigars and newspapers. Frances' parents divorced when she was three. (2)

In 1911 Sonia met a Texan named Morris Brown. After their marriage they moved to Galveston. Ken Cuthbertson has pointed out: "Frances had been deeply attached to her natural father. Her feelings of betrayal at the breakup of her parents' marriage turned to hatred for a stepfather who sexually abused her. The depth of Frances's emotional trauma manifested itself in later life in the form of a self-destructive ambivalence towards men. She was filled with a seething mistrust and resentment of males, yet she craved the paternal affection that had been denied her." (3)

Education

After finishing her high-school education in Texas she moved back to New York and enrolled at Barnard College in 1916. Frances joined the Socialist Club and the Journalism Club in her first year. She apposed the United States participation in the First World War. After being deeply influenced by the work of Karl Marx she agitated against militarism and for world peace and became associated with ant-war protesters at Columbia University, such as the historian, Charles Beard. Columbia's president, Nicholas Murray Butler defined pacifism as sedition: "What had been folly, was now treason." Beard resigned his position in protest, denouncing Columbia's leadership as "reactionary and visionless in politics, narrow and medieval in religion." (4)

Butler insisted that Frances should be expelled from Barnard College because of her anti-war protests. He claimed that it was unwise to waste a Barnard education on such an "undesirable person". (5) She enrolled for a year at the Rice Institute in Houston until they discovered the circumstances of her dismissal from Barnard. Frances did not mind as she was unhappy at the college because of its silly rules: "Tennis shoes shall be put on and taken off in the building and not in the Quadrangle. Students must not go off the College grounds without hats on." Then she studied at Radcliffe College, before returning to Barnard to complete her Bachelor of Arts degree in June 1921. (6)

In 1924 Frances Fineman and a girlfriend decided to travel to Europe and the Soviet Union. In Moscow she wrote an article on the theatre scene for the New York Times. She was especially impressed by the work of Vsevolod Meyerhold: "Meyerhold has made of The Destruction of Europe one of the most exciting productions of his career. Dramatized with wide modifications from a recent novel by the popular modernist Erenborg, the play deals with the plot of an American trust to wipe out the whole of Europe. The seventeen lively episodes on board an American steamer, in the French Chamber of Deputies, the drawing room of the Polish Premier, satirizing Paderewski, a Berlin cabaret, an ethnological meeting in London, a Moscow trades union hall, the centre of an exploding transatlantic tunnel, and others afford Meyerhold the widest scope for the scenic use of his dynamic 'murs mobiles'. These moving walls, aided by the masterly use of spot lighting, give a Twentieth Century Limited rush of movement to the play. As theatre even more strikingly than as propaganda Meyerhold's production is the most revolutionary to be seen in Russia." (7)

John Gunther

In 1925 she moved to France and lived in a small flat in Paris. It was here that she met the American journalist, John Gunther, who was the foreign correspondent for Chicago Daily News. Gunther was entranced by Frances who he described as "a small corn-colored haired creature". He admitted that "she tantalized him, excited him more than he'd been excited before". His friends started to call her the "fatal Frances" (8) Gunther told Helen Hahn: "This Francis girl is fun. She is small and blond and has just returned from six months alone in Moscow whither she went looking for adventure." (9)

Despite their contrasting personalities, Francis was attracted towards Gunther: "He was bright, warm, generous, amicable, and seemed bound for a successful career in journalism. What's more, his commanding physical presence promised a physical security she craved. She was irresistibly drawn to him. The irony was that his mannerisms and fair hair reminded her of her hatred stepfather. (10)

John Gunther married Frances Fineman at the old city hall in Rome on 16th March, 1927. Neither bride nor groom had any relatives present at the ceremony. Lizette Gunther, his mother, would only learn of her son's marriage third-hand: "John Gunther is Wed After Cable Romance" read the headline in the Chicago Daily News. (11)

In August 1928 Frances and her husband travelled to the Soviet Union and spent time with Walter Duranty who had been the New York Times correspondent in the Soviet Union since the Russian Revolution. Gunther was fascinated by the Moscow's street life. "He described in vivid detail the colourful scenes at the small, free-enterprise markets and on the street corners, where buskers, hawkers, and a myriad of itinerant sidewalk tradesmen gathered nightly to sell their wares". (12) As he wrote in the Chicago Daily News: "Perhaps the first impression is the almost total absence of automobiles. The few that we do see are relics of an almost neolithic past, strange monsters with distorted body lines, paintless fenders, grotesquely fanciful hoods." (13)

John Gunther later admitted that in his articles he had relied too heavily on information provided by Walter Duranty. It has been argued by James William Crowl, the author of Angels in Stalin's Paradise (1982) that Duranty had been corrupted by the Soviet government. He had been given a rent free building in central Moscow. In his new home he entered visitors like Gunther, Sinclair Lewis and George Bernard Shaw. (14)

Frances Fineman believed that John Gunther was easily fooled because of his inability to analyse. Her criticisms began with her husband's lack of interest in politics. "What about those interviews of yours? You ask a man what he ate for breakfast and you write about the contours of his waxed moustache, but why? Does any of it matter? If you're going to understand anything, she insisted, you can't glide along the surface." (15)

Chicago

John and Frances returned to live in Chicago. Judith Gunther was born on 25th September, 1928. Unfortunately she died four months later. An autopsy revealed that she was a victim of an undiagnosed thymus ailment known as status thymicolymphaticus. Ken Cuthbertson has pointed out: "Tortured by feelings of guilt at having aborted several unwanted pregnancies, she now became obsessed with the notion that Judy's death was a cruel form of divine retribution for her past indiscretions." (16)

"It's Judy's day," Frances would write on the baby's birthday in the years that followed. "Whenever you do anything grand, I always want to tell her," she told John. "I'd have been so much happier if my sweet little daughter hadn't died, she said of herself later. They buried Judy in Chicago. Then they went to Carmel for a holiday. It was there, in a cottage by the sea, that their second child, Johnny, was conceived. (17)

Vienna

In June 1930, John Gunther became the Chicago Daily News journalist based in Vienna. He soon became close friends with Marcel Fodor, who worked for the Manchester Guardian. Another friend working in the city was William L. Shirer. The two men played tennis together. They also explored the city together and Gunther later recalled that it was "the friendliest city in Europe". Shirer argued that Gunther was an excellent journalist: "John Gunther would go to a country and he'd immediately want to know who had the power, who made the decisions, who had the money, those sorts of things. Wherever he went, he'd always want to interview the king, or the president, or the prime minister." (18)

Dorothy Thompson and Sinclair Lewis in Vienna in 1930.

Dorothy Thompson, Hubert Knickerbocker, Edgar Ansel Mowrer, Marcel Fodor and George Seldes were other newspaper friends who also spent a lot of time in the city during this period. They used to meet at the Café Louvre. A student, J. William Fulbright, on a visit to the city, later recalled: "You could find a group of journalists there most evenings. I remember hearing Fodor hold forth, and he and I became friends. Fodor was a short, stocky man with a mustache, and it was obvious that he was very intelligent; he spoke with great authority on an astounding range of subjects... He had an insatiable curiosity about everything and was a natural teacher." (19)

Frances Fineman became the Vienna correspondent for the News Chronicle. In April 1934 Fineman was arrested while reporting a political meeting being held by Dr. Karl Winter, Commissary Deputy Mayor of Vienna. According to the The New York Times: "When Mrs. Gunther got outside a policeman seized her by the shoulder and marched her off to the police station despite her protest that she was an American journalist. At the police station she found fourteen others, all Austrians, who had been arrested.... The other Austrians were locked in cells, but Mrs. Gunther, after she had warned the police against imprisoning an American journalist, was only detained in the police common room. She was roughly treated there, however, and despite her protests was detained for more than three hours. Her request that Chancellor Dollfuss, to whom she is well known, should be communicated with met with roars of laughter. Finally, after midnight, Dr. Winter's protests had some effect and after the prisoners had been questioned with a view to prosecution they were all released." (20)

Frances Fineman gained a reputation for fearless reporting and she was accused of spreading "atrocity stories". In April 1935, she was forced to leave her job when her husband took a job in London. Her editor, Cecil Gabbertas, said he was sad to see her go: "If every foreign correspondent were of your caliber my life would be a bed of roses." (21)

Inside Europe

In 1934 Cass Canfield of Harper & Brothers approached Hubert Knickerbocker, who had recently won the Pulitzer Prize for reporting, and suggested that he wrote a serious and comprehensive book about Europe. Knickerbocker was in the middle of another project and replied: "Try John Gunther. He's the only one with the brains, the brass, and the gusto to write the book you want." (22)

John Gunther also said he was too busy. In his book, A Fragment of Autobiography (1962) Gunther wrote: "I continued to say no. In those days I was more interested in fiction than in journalism and my dreams were tied up in a long novel about Vienna that I hoped to write... I persisted in saying no to the project, and finally Miss Baumgarten asked me what, if any, financial advance would induce me to change my mind. To cut the whole matter off, I named the largest sum I had ever heard of - $5,000." (23)

Canfield said yes and in his autobiography, Up, Down and Around (1972) argued: "I had the strong feeling that the book would not only sell but blaze a new trail." (24) Gunther later recalled how he did his research for the book in the Atlantic Magazine: "I should equip myself to be able to give information, since it's always easier to ask for something if you offer something in exchange. Journalism is really a process of barter between two people who each know something and find it to their advantage to exchange or pool their knowledge." (25)

Frances Fineman Gunther helped her husband with the research and it has been claimed that she should have been recorded as the co-author. In 1935 he visited London, Paris, Rome, Berlin, Warsaw and Moscow. Gunther also met Hubert Knickerbocker who was based in Nazi Germany at the time. Knickerbocker shared his vast store of firsthand inside information on Adolf Hitler, Joseph Stalin and Benito Mussolini. (26)

The 510-page Inside Europe was published in January 1936. Harold Nicholson, reviewed the book for The Daily Telegraph and argued: "I regard this book as a serious contribution to contemporary knowledge... Fair, intelligent, balanced and well-informed... It will provide the intelligent reader with exactly that sort of information on current affairs which he desires to possess and which he can acquire from no other equally readable source... This is one of the most educative as well as one of the most exciting books which I have read for years." (27)

Indian Independence

Frances Fineman was a strong critic of the British Empire. She upset readers of the British newspaper, Sunday Referee, with her views on the quality of life of people in England: "Nowhere I have seen such poor ugly wretched miserable deformed decrepit low grade physical specimens of humanity." (28) The readers retorted by pointing out that America was also deeply flawed. She replied: "The fact that America is selfish, corrupt, stupid, puritanical, unjust, intolerant, gangsteric, goldhoarding, lynching, and poignantly incapable of talk is No Excuse for the fact that England is a lot of unpleasant things." (29)

Frances also become involved in the struggle for Indian independence. She had first met Jawaharial Nehru in London. Ken Cuthbertson has argued: "Francis was still groping for an elusive something that she felt John was unwilling - or incapable - of giving her. She found what she thought she was seeking in the person of the romantic, strikingly handsome Indian dissident named Jawaharlal Nehru." (30)

In October 1940, Gandhi and Nehru decided to launch a limited civil disobedience campaign in which leading advocates of Indian independence were selected to participate one by one. Nehru was arrested and sentenced to four years imprisonment. Frances decided to support the campaign for Indian independence and joined the executive of the Indian League of America. Other members included Vincent Sheean, William L. Shirer, Pearl S. Buck and Clare Boothe Luce. (31)

Frances Fineman was one of the fiercest and most visible campaigners for Indian independence in the United States. She wrote a series of articles on India for the progressive magazine, Common Sense. She pointed out that Winston Churchill had said that Britain could not afford to give up India. Frances commented that the idea that Britain had to depend on India was "rather a humiliating confession". (32)

In her book, Revolution in India (1944) Frances argued that India was not a boon for the British but a weakness. The possession of India had deformed the British economy as much as the Indian one. Worse, it had created a "political psycho-pathology" of "power and pride, violence, shame, compulsion and much concealed bloodshed" that made Britain cling to its Indian confession?" (33)

Divorce

In the autumn of 1941 John Gunther moved to London where he resumed his affair with Lee Miller, who had been photographing the Blitz for Vogue Magazine. He interviewed Winston Churchill, David Lloyd George, Ernest Bevin, Charles de Gaulle and Juan Negrin, He also met up with old friends, Aneurin Bevan, Harold Nicholson, Rebecca West and Edward Murrow. They all asked Gunther the same question, "Were the Americans going to be in - or out?" (34)

John Gunther found living in London exciting. He wrote in his diary the sense of collective purpose was infectious. In the cinemas, British audiences cheered the Red Army louder than they did their own, and to his surprise, Joseph Stalin got more applause than Churchill. In British factories, workers were producing at top speed, they told him, for the defence of their Russian comrades. (35)

Frances Fineman Gunther remained in America. John Gunther had a series of affairs. This included long relationships with actress Miriam Hopkins and journalist Clare Boothe Luce, the wife of Henry Luce, the owner of Time and Life magazines. He was also a regular at Polly Adler's midtown brothel. According to Deborah Cohen: "John kept lists of girls and sexual ventures the way he'd once enumerated the varieties of battleships or epochal moments in history... Eleven orgasms in the last eight days, he wrote down." (36)

John and Frances Gunther were divorced in March 1944. The New York Times reported that "John Gunther, author and foreign correspondent, obtained a divorce today from Frances Gunther. He charged that she deserted him in 1941. Judge George E. Marshall awarded to Mrs. Gunther custody of their child, John Jr. 15, together with $200 a month for his support and $600 monthly allowance." (37)

In the early months of 1946 Johnny Gunther became seriously ill. At first they thought he was suffering from polio. Later it was discovered that he had a tumor pressing on Johnny's right optic nerve. On 29th April, 16 year-old Johnny went into the operating room for six hours of exploratory surgery. The doctor found a tumor the size of an orange growing in the right occipital parietal lobe but was only able to remove half of it. (38)

The doctor left the boy's skull open, covering the incision in the bone with a bandaged flap of scalp. The technique was intended to give the tumor room to bulge outwards without exerting killing pressure on the rest of Johnny's brain. John Gunther wrote: "All that goes into a brain - the goodness, the wit, the sum total of enchantment in a personality, the very will, indeed the ego itself - was being killed inexorably, remorselessly, by an evil growth." (39)

On 30th June, 1947, Johnny suffered a cerebral hemorrhage. The tumor had eroded a blood vessel inside his head. "John and Frances were alone in the room with Johnny when he died that night. The doctors and nurses were all tending to an emergency elsewhere when Johnny suddenly began to fight for breath. He gasped, and trembled. Then he was still. Johnny's suffering had ended." (40)

Israel

Frances Fineman was also a passionate campaigner for a Jewish state. Her long-term lover, Jawaharial Nehru, disagreed with her on this issue. Nehru believed the idea of a Jewish state in Palestine as a violation of Arab rights to self-determination. John Gunther agreed and argued the Indian Independence movement and Irgun were at "opposite ends of the conventional left-right spectrum: Jabotinsky's Irgun militaristic and right-wing, the Indian National Congress liberal, even socialistic, and pledged to Gandhian nonviolence." (41)

Over this issue Frances was willing to advocate violence to establish the state of Israel. She helped Peter Bergson to get a visa to the United States and then joined his campaign to raise money for a Jewish Army. This upset American Jewish organisations who were worried about stirring up more anti-Semitism in the United States. In reply to Nehru she argued that the Arabs of Palestine could settle elsewhere; they had seven countries ready to welcome them. The Jews only had one homeland. (42)

Frances did get support from her brother, Bernard P. Fineman, who used his contacts to acquire armaments for Irgun. Bernie was eventually indicted by a Grand Jury for his crimes. According to Frances: "I believe the State Department sort of winked at all this because they knew that if Israel wasn't getting arms from us, they'd have gotten them from the communist countries. Evidently this was embarrassing for Washington, and so Bernie was allowed to skip out (went to live in Israel)". (43)

On the founding of Israel in the summer of 1948, Frances sold her house and moved to Jerusalem. "It's quite little, compared to some of the enormous old places, but it has turned out quite comfortable; tiny kitchen and very small bedroom, little study, and long graceful living room." (44) In her apartment she held a salon to try and reconcile her Israeli and Palestinian friends. (45)

Frances managed to find some work writing press releases for the Israeli information office. However, she did not enjoy the experience. (46) Frances turned to freelance writing. In the early 1950s her byline appeared on a regular basis in the Jerusalem Post, the local English language daily. Mostly she wrote articles and book reviews. Frances also lectured on Indian affairs. She also became involved in Hebrew education, which was designed to immerse immigrants in all aspects of life in Israel. (47)

According to her friend Dr. Alexander Rafaeli, Frances had several brief relationships: "Frances was a very lonely woman. She was divorced, and had lost her children. She suffered a great deal during those years. All of her friends here tried to help her, although probably not enough. She had always been a very active woman, who loved people and company." (48)

Frances Fineman's health deteriorated steadily in late 1963 By February, 1964, she was bedridden. She died, aged sixty-seven, on 6th April at the Notre Dame Hospital for the terminally ill in Jerusalem. Her last words were, "I am so tired. Let me sleep." (49)

Primary Sources

(1) Francis Fineman, New York Times (11th January, 1925)

Outstanding events of the present theatrical season in Moscow are Meyerhold's production of a new Russian play, "The Destruction of Europe"; Shaw's "Saint Joan," produced by Tairov; Aristophanes's "Lysistrata." produced by the Moscow Art Theatre, and a new production of "Hamlet" by the Second Moscow Art Theatre, with Chehov, nephew of the dramatist, playing the Prince.

Meyerhold has made of "The Destruction of Europe" one of the most exciting productions of his career. Dramatized with wide modifications from a recent novel by the popular modernist Erenborg, the play deals with the plot of an American trust to wipe out the whole of Europe. The seventeen lively episodes on board an American steamer, in the French Chamber of Deputies, the drawing room of the Polish Premier, satirizing Paderewski, a Berlin cabaret, an ethnological meeting in London, a Moscow trades union hall, the centre of an exploding transatlantic tunnel, and others afford Meyerhold the widest scope for the scenic use of his dynamic "murs mobiles." These moving walls, aided by the masterly use of spot lighting, give a Twentieth Century Limited rush of movement to the play. As theatre even more strikingly than as propaganda Meyerhold's production is the most revolutionary to be seen in Russia.

Shaw might find the "Saint Joan" of the Kamerny Theatre an Interesting play, but he would hardly take a bow to cries of "Author! Author!" Tairov, by changing the emphasis and cutting the text-some cuts are his own and some are the censors'-has remodeled Joan completely. Not only are the court and church characters played in a high pitch of burlesque throughout - even when Shaw grants them their moments of rationalization - but Joan herself is farced. As the leader of the army, she appears in a comic operetta costume consisting of a permanently waved bob, tight breeches, white riding boots with high heels, and white kid gloves. She slaps her thighs, clicks her heels and makes movie eyes. Alice Koonen, wife of Tairov, plays the rôle. The scenery is Impressionistic and economic, the architectural illusions being effectively created by the use of narrow columns of bare wood. Screen slides of Rheims. Notre Dame and sculptured Joans are introduced in the epilogue.

Aristophanes would be better pleased with Nemirovitch-Dantchenko's handling of "Lysistrata." The translation is free and unexpurgated. The play is set in an extraordinarily beautiful circular white temple against a changing sky. At the dress rehearsal of "Hamlet,' which was attended by critics, artists and members of the Government, Chehov was made a People's Artist of the Republic, the highest honor that can be bestowed. Chaliapin, Meyerhold and Stanislavsky are among the few who have received this title. "Hamlet" will undoubtedly be in the répertoire of the Second Moscow Art Theatre when Morris Gest brings the company to America within the next year or two. The theatre was formerly known as the First Studio of the parent organization, and bears its new name for the first time this year. The production was staged by three regisseurs, and shows a consequent lack of unity. The scenic design on the whole is conservatively impressionistic, but there is a single scene, that of Laertes's return, done after Meyerhold's most dynamic manner.

Chehov's Hamlet is the passive, Inert, morbidly introspective hero of the old Russian realism. The King, on the other hand, plays the bloody villain of bloodiest melodrama. And the courtiers furnish the note of satiric caricature which shows the influence of the revolution. They are all costumed alike, and move like puppets in mechanical unison. As to the Ghost, Hamlet himself speaks his lines, on a dark stage, to the dimly heard accompaniment of the music of muffled drums. Press comment on the production has been lively and varied. The Izvestia asks whether "Hamletism is necessary or living to us?" The conservative critic of the Pravda speaks of the universality of Hamlet, who does not think, but feels. Blum, critic of the Novi Zritel, and one of the State censors, says this is not feeling, but hysteria. "We see his sickness with cold eyes. He gives us the dying world, but we want a living one."

(2) Francis Fineman, New York Times (27 September 1925)

Oliver Sayler in the September "Vanity Fair" wrote a pretty good press agent yarn about the Moscow Art Theatre's "Carmencita," but a pretty poor news story. The exciting thing about this production is not that the play is fifty years old, or that Galli-Marié played it in 1875, or even that the restless Gest sent a grand petition to the tranquil Anatol V. Lunacharsky. The exciting thing is the work done by one Isaac Rabinovitch, whom Mr. Sayler tucks away in a single sentence in the penultimate paragraph as the deviser of "costumes simple and yet startling in cut and contour and flaming in intense reds and yellows."

Rabinovitch's set and costumes are, as a matter of fact, the most interesting and original part of the production. To Nemirovitch-Dantchenko, the partner of Stanislavsky, belongs the credit of having the courage to accept them. Not an easy thing to do when you consider Stanislavsky's almost paralytic rigidity in maintaining the strict classic tradition of his theatre, one of the few survivors of that tradition in Moscow today. As one critic put it to me: "Stanislavsky is a great artist, but Dantchenko has his ear to the ground." During Stanislavsky's absence in America, Dantchenko, realizing that if the theatre were to go on, it would have to adapt itself to changing conditions, inaugurated the Musical Studio, permitting a more or less free hand to young talent. Stanislavsky has never quite forgiven his partner for this departure, and the resultant coolness in their old friendship is one of the many tragic by-products of adjustment to the revolution.

Rabinovitch is about 30. He studied at the Kiev Art School (which was also attended by Alexandra Exter of Tairov-cubist-Salome fame). He has been designing for the theatre for the past six or seven years and is recognized as the most talented of the younger scene artists.

New York will have an excellent opportunity of judging the versatility of his work this Winter. The Art Theatre will present his designs in "Carmencita" and "Lysistrata." And - unless plans made in Moscow this Spring have miscarried�a third and entirely different angle of his work will be seen in the production of "Koldunia" ("The Sorceress") by Granovsky's Moscow Jewish Theatre.

(3) The New York Times (April 25, 1934)

The experiment of "free speech on sufferance" attempted by Dr. Karl Winter, Commissary Deputy Mayor of Vienna, culminated last night in a raid on his meeting by the police, who arrested fifteen of those present, including an American woman journalist, Mrs. Frances Gunther, whose husband is the correspondent of The Chicago Daily News in Vienna.

Dr. Winter's meeting was raided without his authority, although he is an official of the Fascist government. Before the raid a man who had made an interjection during a speech by Dr. Winter was arrested by one of the police spies posted in all parts of the hall. Thereupon the workers sang the forbidden "Internationale" and demanded his release before the speeches were continued. Dr. Winter promised to make good his guarantee of immunity and obtain the man's release subsequently. In the midst of the speech made by the second worker to address the meeting the police broke into the hall, drew their clubs and drove the workers into the street.

When Mrs. Gunther got outside a policeman seized her by the shoulder and marched her off to the police station despite her protest that she was an American journalist.

At the police station she found fourteen others, all Austrians, who had been arrested. Among them were two white-haired old women and a man well over 60 years old. None of them had any idea why they had been arrested. One girl had fallen to the floor in a fit when the police raided the meeting. The other Austrians were locked in cells, but Mrs. Gunther, after she had warned the police against imprisoning an American journalist, was only detained in the police common room. She was roughly treated there, however, and despite her protests was detained for more than three hours. Her request that Chancellor Dollfuss, to whom she is well known, should be communicated with met with roars of laughter. Finally, after midnight, Dr. Winter's protests had some effect and after the prisoners had been questioned with a view to prosecution they were all released.

Tonight's newspapers announce the end of Dr. Winter's courageous experiment to establish free speech under Fascism. In the future he will not be allowed to hold any open meetings. Only selected persons specially invited will be allowed to attend, and before any one speaks full particulars about him will be registered from his identity card so that if he makes any remarks unpalatable to the government he can be suitably dealt with.

Mrs. Gunther is one of several Anglo-Saxons who have been summarily arrested since the Fascist triumph in Austria. Among others were two Englishwomen, one of whom, Mrs. Betty Waddington, a connection of the British royal family by marriage, had been giving charitable aid to the family of an imprisoned Socialist out of her private purse.

Another was the Canadian diplomat Percival Price, who, despite his diplomatic passport, was arrested, taken handcuffed through the main streets of Vienna to police headquarters and there imprisoned for thirteen hours, merely because by looking hurriedly into the barber shop where Chancellor Dollfuss is shaved daily and departing without saying he had been attended, he had awakened the suspicion of the secret police, who imagined he was plotting to murder the Chancellor.

(4) The New York Times (7th April, 1964)

Frances Gunther, a writer and former wife of John Gunther, the author, died in Jerusalem today. She was 67 years old. Her brother, Bernard P. Fineman of Los Angeles, was at her bedside.

Mrs. Gunther, who was born in New York, attended Radcliffe College and was graduated from Bernard College. She wrote books and articles for newspapers and magazines and was a former foreign correspondent.

At her death, she had been writing a book on the impact of Judaism, Christianity and Islam on politics and history.

Mrs. Gunther, who was a member of the executive committee of American Friends of a Jewish Palestine, long campaigned for the Zionist cause.

(5) Ken Cuthbertson, Inside: The Biography of John Gunther (1992)

Frances had been deeply attached to her natural father. Her feelings of betrayal at the breakup of her parents' marriage turned to hatred for a stepfather who sexually abused her. The depth of Frances's emotional trauma manifested itself in later life in the form of a self-destructive ambivalence towards men. She was filled with a seething mistrust and resentment of males, yet she craved the paternal affection that had been denied her. Frances was haunted by a sense of guilt that she had somehow been responsible for Brown's misdeeds. Incest being a crime not spoken of in 1911, Frances was left to wonder at the meaning of it all. It was a burden that no fourteen-year-old could bear alone, and the scars never fully healed.

References

(1) Ken Cuthbertson, Inside: The Biography of John Gunther (1992) page 65

(2) Deborah Cohen, Last Call at the Hotel Imperial: The Reporters Who Took on a World at War (2022) pages 26-27

(3) Ken Cuthbertson, Inside: The Biography of John Gunther (1992) page 69

(4) Richard Hofstadter and Walter P. Metzger, The Development of Academic Freedom in the United States (1955) pages 498-502

(5) Frances Fineman, student file (23rd July 1918)

(6) Deborah Cohen, Last Call at the Hotel Imperial: The Reporters Who Took on a World at War (2022) page 30

(7) Frances Fineman, New York Times (11th January, 1925)

(8) Deborah Cohen, Last Call at the Hotel Imperial: The Reporters Who Took on a World at War (2022) page 52

(9) John Gunther, letter to Helen Hahn (3rd June, 1925)

(10) Ken Cuthbertson, Inside: The Biography of John Gunther (1992) page 70

(11) Deborah Cohen, Last Call at the Hotel Imperial: The Reporters Who Took on a World at War (2022) page 30

(12) Ken Cuthbertson, Inside: The Biography of John Gunther (1992) page 82

(13) John Gunther, Chicago Daily News (23rd August, 1928)

(14) James William Crowl, Angels in Stalin's Paradise (1982) pages 33-34

(15) Deborah Cohen, Last Call at the Hotel Imperial: The Reporters Who Took on a World at War (2022) page 124

(16) Ken Cuthbertson, Inside: The Biography of John Gunther (1992) page 87

(17) Deborah Cohen, Last Call at the Hotel Imperial: The Reporters Who Took on a World at War (2022) pages 109-110

(18) William L. Shirer, interview with Ken Cuthbertson (10th November, 1986)

(19) William L. Shirer, interview with Ken Cuthbertson (6th June, 1986)

(20) The New York Times (April 25, 1934)

(21) Cecil Gabbertas, letter to Frances Fineman (8th April, 1935)

(22) Cass Canfield, Up, Down and Around (1972) page 123

(23) John Gunther, A Fragment of Autobiography (1962) page 7

(24) Cass Canfield, Up, Down and Around (1972) page 123

(25) John Gunther, Atlantic Magazine (April, 1937)

(26) Ken Cuthbertson, Inside: The Biography of John Gunther (1992) pages 130-133

(27) Harold Nicholson, The Daily Telegraph (17th January, 1936)

(28) Frances Fineman, Sunday Referee (18th August 1935)

(29) Deborah Cohen, Last Call at the Hotel Imperial: The Reporters Who Took on a World at War (2022) page 217

(30) Ken Cuthbertson, Inside: The Biography of John Gunther (1992) page 165

(31) M.S. Venkataramani and B. K. Shrivastava, Quit India: The American Response to the 1942 Struggle (1979) pages 290-293

(32) Frances Fineman, Common Sense (January 1943)

(33) Frances Fineman, Revolution in India (1944) page 11

(34) Deborah Cohen, Last Call at the Hotel Imperial: The Reporters Who Took on a World at War (2022) page 327

(35) John Gunther, diary entry (27th November 1941)

(36) Deborah Cohen, Last Call at the Hotel Imperial: The Reporters Who Took on a World at War (2022) page 329

(37) The New York Times (9th March, 1944)

(38) John Gunther, Death Be Not Proud (1949) page 42

(39) John Gunther, Death Be Not Proud (1949) page 107

(40) Ken Cuthbertson, Inside: The Biography of John Gunther (1992) page 280

(41) Deborah Cohen, Last Call at the Hotel Imperial: The Reporters Who Took on a World at War (2022) page 334

(42) Frances Fineman, letter to Jawaharial Nehru (March, 1938)

(43) Ken Cuthbertson, Inside: The Biography of John Gunther (1992) page 351

(44) Frances Fineman, letter to John Gunther (4th July 1953)

(45) Deborah Cohen, Last Call at the Hotel Imperial: The Reporters Who Took on a World at War (2022) page 402

(46) Frances Fineman, letter to John Gunther (22nd July 1951)

(47) Ken Cuthbertson, Inside: The Biography of John Gunther (1992) page 357

(48) Ken Cuthbertson, interview with Dr. Alexander Rafaeli (24th October, 1991)

(49) Ken Cuthbertson, Inside: The Biography of John Gunther (1992) page 361