On this day on 12th April

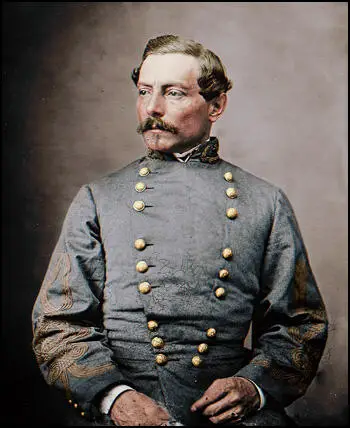

On this day in 1861 General Pierre T. Beauregard demanded that Major Robert Anderson surrender Fort Sumter in Charleston harbour. Anderson replied that he would be willing to leave the fort in two days when his supplies were exhausted. Beauregard rejected this offer and ordered his Confederate troops to open fire. After 34 hours of bombardment the fort was severely damaged and Anderson was forced to surrender.

On hearing the news, Abraham Lincoln called a special session of Congress and proclaimed a blockade of Gulf of Mexico ports. This strategy was based on the Anaconda Plan developed by General Winfield Scott, the commanding general of the Union Army. It involved the army occupying the line of the Mississippi and blockading Confederate ports. Scott believed if this was done successfully the South would negotiate a peace deal. However, at the start of the war, the US Navy had only a small number of ships and was in no position to guard all 3,000 miles of Southern coast.

On 15th April, 1861, President Lincoln called on the governors of the Northern states to provide 75,000 militia to serve for three months in order to put down the insurrection. Virginia, North Carolina, Arkansas and Tennessee, all refused to send troops and joined the Confederacy. Kentucky and Missouri were also unwilling to supply men for the Union Army but decided not to take sides in the conflict.

Some states responded well to Lincoln's call for volunteers. The governor of Pennsylvania offered 25 regiments, whereas Ohio provided 22. Most men were encouraged to enlist by bounties offered by state governments. This money attracted the poor and the unemployed. Many African Americans also attempted to join the army. However, the War Department quickly announced that it had "no intention to call into service of the Government any coloured soldiers." Instead, black volunteers were given jobs as camp attendants, waiters and cooks.

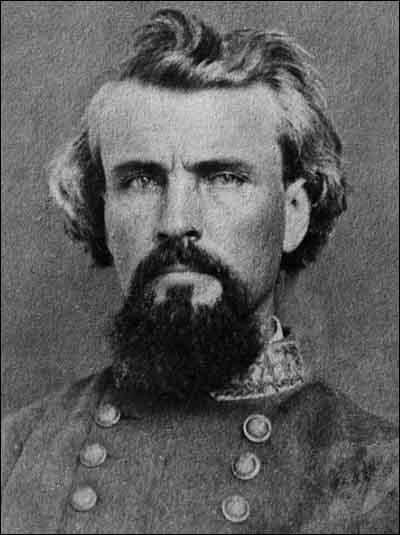

On this day in 1864 General Nathan Forrest attacked Fort Pillow in Jackson, Tennessee. The fort contained 262 African American and 295 white soldiers. It was afterwards claimed that most of these soldiers were killed after they surrendered. After the war an official investigation discovered evidence that "the Confederates were guilty of atrocities which included murdering most of the garrison after it surrendered, burying Negro soldiers alive, and setting fire to tents containing Federal wounded."

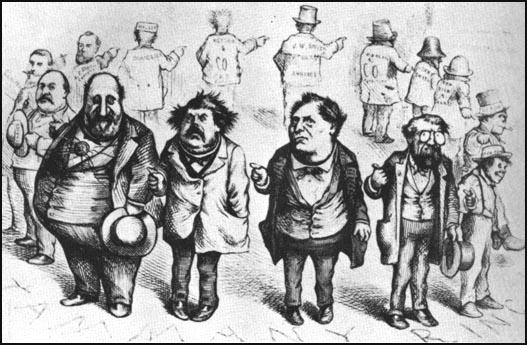

On this day in 1878 William M. Tweed died. Tweed was born in New York in 1823. A chairmaker he eventually became involved in politics and served as a alderman (1852-53) and as a congressman (1853-55). A member of the powerful Tammany Society, by 1865 Tweed and his three loyal companions, Peter Sweeney, Richard Connolly and Oakley Hall, ruled New York like despots.

In 1870 Tweed was appointed as commissioner of public works in New York. This enabled Tweed to carry out wholesale corruption. For example, he purchased 300 benches for $5 each and resold them to the city for $600. Tweed also organised the building of City Hall Park. Originally estimated to cost $350,000, by the time it was finished, expenditure had reached $13,000,000.

Information about Tweed's corrupt activities were passed to Thomas Nast, a cartoonist working for Harper's Weekly. Nast now began a campaign to expose Tweed's corruption. Tweed was furious and told the editor: "I don't care a straw for your newspaper articles, my constituents don't know how to read, but they can't help seeing them damned pictures."

Pressure was put on Harper Brothers, the company that produced the magazine, and when it refused to sack Thomas Nast, the company lost the contract to provide New York schools with books. Nast himself was offered a $500,000 bribe to end his campaign. This was hundred times the salary of $5,000 that the magazine paid him but Nast still refused to back-down.

On 21st July, the New York Times published the contents of the New York County ledger books. This revealed that thermometers were costing $7,500 and brooms were being charged at a staggering $41,190 apiece. Tweed's friends were commissioned to do the work. George Miller, a carpenter, was paid $360,747 for a month's labour, whereas James Ingersoll received $5,691,144 for furniture and carpets.

In 1871 Samuel Tilden established a committee to look into Tweed's activities. Other prominent political figures in New York such as Joseph Seligman and Richard Croker now became involved in the campaign against Tweed. Jimmy O'Brien, the sheriff of New York, believed Tweed was not paying him enough money for his services. Disgruntled, he passed documents to Tilden's committee.

Tweed was arrested and found guilty of corruption, was sentenced to 12 years in jail. Tweed, who had made an estimated $200,000,000 from his activities, was able to use his wealth to escape from prison. Tweed fled to Cuba, before moving on to Spain. An American in Spain recognised Tweed from one of Nast's cartoons that he had. He used the cartoon to convince the authorities and Tweed was arrested and sent back to the United States. William Tweed died in prison in 1878.

Sweeney, Richard Connolly and Oakley Hall that appeared in Harper's Weekly (19th August, 1871)

On this day in 1912 Clara Barton, died. Barton was born in Oxford, Massachusetts, on 25th December, 1821. The daughter of a farmer, Barton began work as a schoolteacher at the age of fifteen.

In 1850 Barton moved to New York where she attended the Clinton Liberal Institute. Two years later she moved to Bordentown, New Jersey, where she established a free school. The school was very popular and grew rapidly. This upset the local men in the town and they tried to insist that the school should be run by a man. Barton refused and moved to Washington where she found work as a clerk in the U.S. Patent Office. In doing so, Barton became one of the first women to join the civil service.

On the outbreak of the American Civil War, Barton became a strong supporter of the Union cause. After hearing about the heavy casualties at Bull Run, Barton advertised in newspapers for medical supplies for the wounded. The response was so good that she was able to set up an agency distributing goods to soldiers. This involved the hiring of mules and wagons to take the supplies to the battlefields.

In July, 1862, Clara Barton went to the front-line where she worked as an unpaid nurse for the Army of the Potomac. Barton continued as a freelance nurse until June, 1864, when she was employed as superintendent of nurses for the Army of the James. The following year President Abraham Lincoln appointed her as head of the Bureau of Records, a unit that attempted to search for missing soldiers.

After the war Barton toured Europe and when the Franco-German War broke out in 1870, she organized the distribution of supplies to the French Army. During this period she became associated with the International Red Cross and after her return to the United States in 1873, Barton campaign to persuade the USA to sign the Geneva Convention. This was an agreement which established rules for the care of the sick and wounded in war.

In 1877 Barton organized the American National Committee, which three years later became the American Red Cross. The USA signed the Geneva Convention in 1884 and Congress agreed to support Barton's efforts to distribute relief during floods, earthquakes, famines, cyclones and other peacetime disasters.

The author of the History of the Red Cross (1882), Barton served as president of the American Red Cross between 1882 and 1904. Other books by Barton include The Red Cross in Peace and War (1899) and The Story of My Childhood (1907).

On this day in 1930 Marcus Garvey publishes an article for Pittsburgh Courier on racism. "From early youth I discovered that there was prejudice against me because of my colour, a prejudice that was extended to other members of my race. This annoyed me and helped to inspire me to create sentiment that would act favorably to the black man. It was with this kind of inspiration that I returned from my trip to Europe to Jamaica in 1914, where I organized the Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League. When I organized this movement in Jamaica it was treated with contempt and scorn by a large number of the highly coloured and successful black people. In Jamaica the coloured and successful black people regard themselves as white. This is also true of the other British West Indian islands. The result is that racial movements tending to the betterment of the Negro have to undergo great difficulties. Such difficulties I encountered with the new organization. I labored in Jamaica with the hope of making the movement successful for two years. Seeing how difficult it was to succeed with only a limited amount of money at my disposal, I communicated with Dr. Booker T. Washington of Tuskegee. He encouraged me to go to the United States on a lecture tour and promised me his help. Unfortunately he died before I was able to reach America."

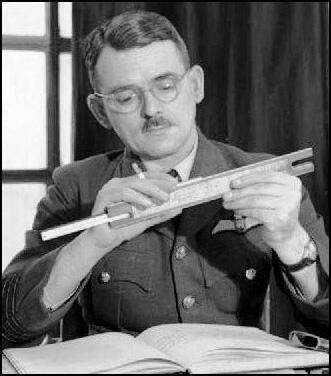

On this day in 1937 Frank Whittle tests the first prototype jet engine.rank. Whittle, the son of a mechanic, was born in Coventry, England, on 1st June, 1907. He joined the Royal Air Force as an apprentice in 1923. He showed outstanding ability as a scientist and in 1929 took out a patent on a turbo-jet engine. However, the Air Ministry rejected his ideas as impractical.

Whittle studied at Cambridge University (1934-37) before forming the Power Jets Company. The Royal Air Force became more interested in Whittle's ideas in 1939 when they heard the news that Hans Ohain in Nazi Germany had developed the world's first jet plane, the HE 178. At first, it was thought that Ohain must have stolen Whittle's ideas but in fact they had both been working independently of each other.

Whittle's jet-propelled Gloster E28 took its first flight on 15th May, 1941 and travelled at speeds of 350 mph. This was followed by the Gloster Meteor that was used to intercept German V1 Flying Bomb. Power Jets Company was taken over by the British government in 1944.

Whittle retired from the Royal Air Force in 1948 with the rank of air commodore. He was knighted and granted a tax-free gift of £100,000 in recognition of his role in developing the jet-engine. He wrote about his experiences in his book, Jet: The Story of a Pioneer (1953).

In 1977 Whittle was appointed research professor at the US Naval Academy in Annapolis. Frank Whittle died in Columbia, Maryland, on 8th August, 1996.

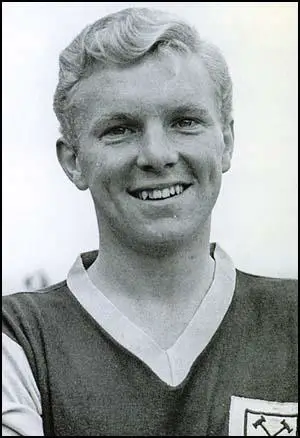

On this day in 1941 Bobby Moore, the only son of Robert (Bob) and Doris Moore, was born in Upney Hospital during the Blitz. His aunt, Ena Herbert, recalled: "Little Robert was delivered in Upney hospital... Doris stayed in the hospital that night and came home to Waverley Gardens the next day... That night there was a very heavy German bombing raid and an explosion in the neighbourhood blasted ceilings down and blew windows in... Bob's mother and Bob laid across the baby and Doris to protect them from injury. The raid was so bad they had to evacuate Doris and little Robert from Waverley Gardens, which was near the industrial area, close to the power station on the river, which was a target for the German bombs."

The Moore family lived at 43 Waverley Gardens in Barking and Bobby attended Westbury Primary School. His parents supported Barking Football Club and attended all their home and away games. Moore passed his 11-plus and went to Tom Hood Technical High School in Leyton. Moore later recalled: "The first two months were murder. I was the only boy from my district. Up at seven a.m., on my own on the bus from home to Barking station, train to Wanstead, trolleybus to Leyton, long walk to the school. I was sick with it. I went to the doctor pining for any sort of school in Barking and got a certificate for a transfer on the grounds of travel sickness." However, Moore decided to continue at the school.

Joan Wright, one of his teachers at Tom Hood Technical High School later recalled: "At school he was a prefect... He was very popular. It was a technical and commercial school and Bobby passed the equivalent of nearly half a dozen 'O' levels in one go. whenever there were pupils who wanted to become footballers and thought they didn't have to try at academic work. I'd point out Bobby Moore as an example to show it is possible to do both."

While at secondary school Moore played for Leyton District Under-13s. During one game he was seen by a West Ham United scout and he was invited to train at Upton Park. Moore found the experience difficult: "I was ordinary. I was lucky to be there. and every time I looked at one of the other lads I knew it. Every one of them had played for Essex or London, and at least been for trials with England Schoolboys. I had nothing. All around me were players with unbelievable ability. They were the same age as me and I was looking up at them and wishing I was that good, that skillful."

Moore later pointed out: "The first time I got a representative game I played for Essex over-15s because they needed a makeshift centre forward. I kept lumbering down the middle until our keeper hit a big up-and-under clearance which their keeper caught as I bundled him into the net... The referee was weak and gave the goal for Essex. Everyone knew it was a joke. Most of all, the lads who knew they were better than me." During this period Moore suffered from an inferiority complex. "The best quality I had was wanting to succeed."

Moore was invited to train with the West Ham Colts. His ability was noticed by Malcolm Allison, the West Ham United defender who had been asked by Ted Fenton, the club manager, to coach the young players. "Fenton used to pay me £3 extra for training the schoolboys at night. It was then that I found I had a bit of a gift for spotting the boys most likely to make it as professionals.... After a fortnight of training the boys Fenton called me into his office to ask my opinion of the intake." Fenton asked him about Georgie Fenn, who had scored nine goals in one match for England Schoolboys: "I said that I didn't give him much of a chance. I didn't like his attitude, he wasn't interested enough. There didn't seem much of a commitment... At the same time I said that Bobby Moore was going to be a very big player indeed. Everything about his approach was right. He was ready to listen. You could see that already he was seeking perfection."

In August 1950, Bobby Moore signed amateur forms for West Ham United. He joined the club full-time after leaving school on 19th July, 1957. Ron Greenwood, was with Fulham when he first saw Bobby Moore play: "I saw Bobby play for London Schoolboys against Glasgow at Stamford Bridge. Even at 16 he had stature, a certain appearance, an awareness of the game others did not possess." When Greenwood became manager of the England Youth team he selected Moore as his captain: "He was thirsty for knowledge and I spent hours talking to him about the game, whenever there was a free moment. When we had trips away he almost raided you for knowledge."

Malcolm Allison also noticed his leadership qualities. "He was very inquisitive. Even then I had spotted his awareness for the game, his ability to recognise things so easily. He had a clever memory and he was very bright. Allison told Moore: "You can read the game, you know what to do... Be in control of yourself. Take control of everything around you. Look big. Think big. Tell people what to do. Be in command." Noel Cantwell was one of the senior players at the club at the time: "Bobby didn't have exceptional ability as an apprentice, although he was always immaculate. He never said very much but was a great listener and a dedicated trainer, always very curious, inquisitive guy who wanted answers. He fastened on to Malcolm Allison and myself because we talked football all the time."

Bobby Moore recalled in his autobiography: "When Malcolm was coaching schoolboys he took a liking to me when I don't think anyone else at West Ham saw anything special in me... I looked up to the man. It's not too strong to say I loved him." Eddie Lewis was a member of the West Ham squad during this period. He observed the help that Allison gave to Moore: "The man deserves a great deal of credit for bringing on the likes of Bobby Moore. As a kid, Bobby was slow, he couldn't head a ball and he couldn't tackle, but such was Malcolm's dedication he was able to help Bobby to become the player he was." Harry Redknapp claims that Allison valued Moore so much that "Malcolm would bring him to training and drive him home."

Moore put a lot of effort into his training. Geoff Hurst recalled: "I remember how impressed I'd been with this blond-haired youngster from Barking when I first started training at West Ham. When we were doing exercises to strengthen the stomach muscles we had to lie on our backs, raise our legs in the air and hold them there. Try it yourself. If you are not used to it you will quickly discover how painful this can be. Of the 50 or so players doing this exercise the last to lower his legs was Bobby Moore. Always." Frank Lampard agreed: "You could see how some trained better than others, some were good runners, some were bad, but every time you looked over at the first team training, Bobby was the one training hard." John Bond was another player who was impressed with Bobby Moore: "Bobby's ability to intake information was tremendous, he wanted to learn and allowed nothing to interfere with his football. People used to tell him things and he would learn very quickly."

Moore played in a youth match against Chelsea where he marked the highly talented Barry Bridges: "I marked Bridges and followed him all over the field, wherever he went. We drew 0-0 and I was really pleased with myself and I thought Malcolm would give me a pat on the back at the end of the game." Instead Malcolm Allison came into the dressing-room and shouted: "If I ever see you play like that again, I'll never talk to you again. You just followed Bridges all over the field. When your goalkeeper got the ball, you never dropped back and made the goalkeeper roll it out so you could start attacks from the back, did you? When your left-back got it, you didn't drop inside so he could pass it square, so you could chip the ball up to the centre-forward, did you? I want to see you do those things and if you can't, don't talk to me. I'm not giving you any more lifts home."

Moore told Harry Redknapp that this outburst completely changed the way he played the game: "If you look at Bobby's game, he would come and get it off the goalie and play it out, starting attacks, and he would drop off, get the ball from the left-back and chip it into Hurstie's chest. That was an essential part of his game."

On 16th September, 1957, Malcolm Allison was taken ill after a game against Sheffield United. Moore later recalled: "I'd even seen him the day he got the news of his illness. I was a groundstaff boy and I'd gone to Upton Park to collect my wages. I saw Malcolm standing on his own on the balcony at the back of the stand. Tears in his eyes. Big Mal actually crying. He'd been coaching me and coaching me and coaching me but I still didn't feel I knew him well enough to go up and ask what was wrong. When I came out of the office I looked up again and Noel Cantwell was standing with his arm round Malcolm. He'd just been told he'd got T.B."

Allison was suffering from tuberculosis and he had to have a lung removed. Noel Cantwell became the new captain. That season West Ham United won the Second Division championship. The authors of The Essential History of West Ham United point out that Allison was the main reason the club had won promotion: "A footballing visionary who in six short years would revolutionise the club's archaic regime and transform training, coaching techniques and tactics to secure promotion to the first division in 1958".

Allison returned to the club and played several games for the reserves but with only one lung he struggled with his fitness. West Ham had an injury crisis for its home game against Manchester United on 8th September 1958. Malcolm Pyke, Bill Lansdowne and Andy Nelson were all injured. The manager, Ted Fenton asked Noel Cantwell who he should select for the game. Cantwell told Brian Belton, the author of Days of Iron: The Story of West Ham United in the Fifties (1999): "The game against Manchester United was on a Monday night. Fenton called me into the office asking who should play left-half, Allison or Moore. He didn't really want the burden of the decision."

Cantwell added in another interview for the book, Moore than a Legend (1997): "Malcolm came out of hospital and trained while Bobby was cruising along in the reserves. Malcolm was ready for the United game but the vacancy was for a left-half. Malcolm was more of a stopper and it needed someone more mobile. When Ted asked me who to pick, it was a hard decision. The sorcerer or his apprentice?" Cantwell eventually selected Moore over Allison.

Bobby Moore later talked about this decision to Jeff Powell for this book, Bobby Moore: The Life and Times of a Sporting Hero (1997): "The Allison connection could only be dredged up from the bottom of a long, long glass. Even then, Moore probed gingerly at the memory". Eventually Moore told him: " After three or four matches they were top of the First Division, due to play Manchester United on the Monday night, and they had run out of left halves. Billy Lansdowne, Andy Nelson, all of them were unfit. It's got to be me or Malcolm. I'd been a professional for two and a half months and Malcolm had taught me everything I knew. For all the money in the world I wanted to play. For all the money in the world I wanted Malcolm to play because he'd worked like a bastard for this one game in the First Division."

Bobby Moore added: "It somehow had to be that when I walked into the dressing room and found out I was playing, Malcolm was the first person I saw. I was embarrassed to look at him. He said Well done. I hope you do well. I knew he meant it but I knew how he felt. For a moment I wanted to push the shirt at him and say Go on, Malcolm. It's yours. Have your game. I can't stop you. Go on, Malcolm. My time will come. But he walked out and I thought maybe my time wouldn't come again. Maybe this would be my only chance. I thought: you've got to be lucky to get the chance, and when the chance comes you've got to be good enough to take it. I went out and played the way Malcolm had always told me to play."

Malcolm Musgrove was a member of the West Ham side that played against Manchester United: "He played in the game as though he'd been in the side for years. I was a lot older than Bobby at the time and I was still a novice, nervous as hell. At the kickoff Bobby stood in the left-half position just looking round. He had an unbelievable temperament. Lots of players have ability, but they haven't got the temperament to make them go even further, as far as they might want to go - Bobby had that temperament."

Moore did a good job marking Ernie Taylor and West Ham won the game 3-2. After the game Malcolm Allison stormed into the dressing-room and confronted Noel Cantwell about the advice he had given Ted Fenton. Cantwell later commented: "How he got to know I had influenced Ted's decision for Bobby to play, I'll never know. I didn't say any more. It was an embarrassing position for me and it soured the night, although I had answered Ted's question with the right choice for the particular match. Later, Malcolm admitted I was right to choose Bobby."

The next game was against Nottingham Forest at home. Moore was dropped from the team after West Ham United lost 4-0. He played only three more games that season as John Smith became the regular left-half. Moore had the same problem in the 1960-61 season. Moore later told Jeff Powell that he "doubted he would ever have broken through had West Ham not sold John Smith to Tottenham". Moore added: "You've got to be lucky even if you know you're good enough to take the chance if it comes. If John hadn't gone to Spurs I might have been a reserve footballer who threw in the towel, gave up the game."

On this day in 1945 General Alan Brooke, Chief of Imperial General Staff writes an assessment of Winston Churchill. "We had to consider this morning one of Winston's worst minutes I have ever seen. I can only believe that he must have been quite tight when he dictated it. My God! How little the world at large knows what his failings and defects are!"

In August 1939 Brooke was appointed head of Southern Command and on the outbreak of the Second World War went to France as a member of the British Expeditionary Force under General John Gort. In June 1940 Brooke played a leading role in the evacuation of British troops at Dunkirk. General Brian Horrocks argued in his autobiography, A Full Life (1960): "The more I have studied this campaign the clearer it becomes that the man who really saved the B.E.F. was our own corps commander, Lieutenant-General A. F. Brooke. I felt vaguely at the time that this alert, seemingly iron, man without a nerve in his body, whom I met from time to time at 3rd Division headquarters and who gave out his orders in short, clipped sentences, was a great soldier, but it is only now that I realise fully just how great he was. We regarded him as a highly efficient military machine. It is only since I have read his diaries that I appreciate what a consummate actor he must have been. Behind the confident mask was the sensitive nature of a man who hated war."

Brooke returned to Britain and in July 1940 he replaced Edmund Ironside as commander of the Home Forces. In this post Brooke had several major disagreements with Winston Churchill about military strategy. It therefore came as a surprise when Churchill appointed him Chief of Imperial Staff in December 1941. General Harold Alexander believed it was a good appointment: "Brookie, as we always call him, was the outstanding and obvious man for the job; a fine soldier in every sense, and trusted and admired by the whole Army."

Although the two men continued to disagree about a large number of issues, for example, Brooke favoured an early invasion of Europe on order to take pressure off the Red Army on the Eastern Front, he gradually became Churchill's most important military adviser in the war.

Alan Brooke was offered command of the British troops in the Middle East in August 1942 but turned it down suggesting General Harold Alexander for the post. In his diary Brooke recorded that it was more important for him to remain in Britain in order to stop Winston Churchill making any major military mistakes. He wrote in his diary: "We had to consider this morning one of Winston's worst minutes I have ever seen. I can only believe that he must have been quite tight when he dictated it. My God! How little the world at large knows what his failings and defects are!"

Churchill had promised Brooke command of Operation Overlord in 1944. However, President Franklin D. Roosevelt insisted that General Dwight Eisenhower should be given this important task. Promoted to field marshal in January 1944 he was created Baron Alanbrooke of Brookeborough in September 1945. After retiring from the British Army he was a director of Midland Bank. Alan Brooke died on 17th June 1963.

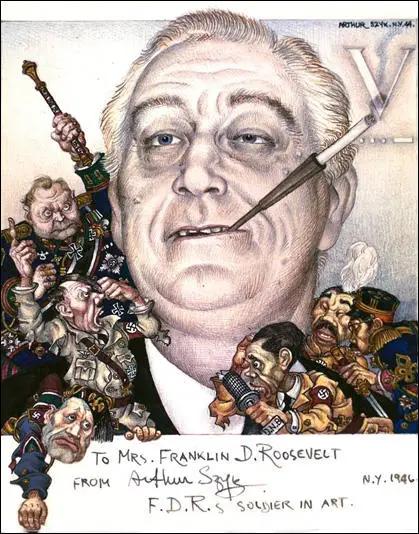

On this day in 1945 President Franklin D. Roosevelt died three weeks before Germany surrendered on 7th May, 1945. Frances Perkins later claimed that Eleanor Roosevelt told her that people would stop her on the street and say "they missed the way the President used to talk to them". They would say "he used to talk to me about my government". Eleanor added: "There was a real dialogue between Franklin and the people. That dialogue seems to have disappeared from the government since he died."