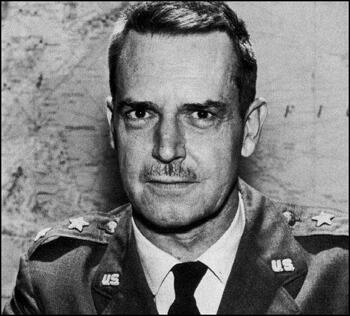

Edward Lansdale

Edward Lansdale was born in Detroit, Michigan, on 6th February, 1908. During the Second World War Lansdale was a member of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), an organization that was given the responsible for espionage and for helping the resistance movement in Europe.

According to Sterling Seagrave, Lansdale was sent by General Charles Willoughby to the Philippines after the war. Lansdale "joined the torture sessions of Major Kojima Kashii "as an observer and participant". As Seagrave explains: "Since Yamashita had arrived from Manchuria in October 1944 to take over the defense of the Philippines, Kojima had driven him everywhere."

In charge of Kojima’s torture was an intelligence officer named Severino Garcia Diaz Santa Romana (Santy). He wanted Major Kojima to reveal each place to which he had taken General Tomoyuki Yamashita, where bullion and other treasure were hidden." Ray Cline argues that between 1945 and 1947 the gold bullion recovered by Santy and Lansdale was moved by ship to 176 accounts at banks in 42 countries. Robert Anderson and CIA agent Paul Helliwell set up these black gold accounts "providing money for political action funds throughout the noncommunist world."

Promoted to the rank of major Lansdale was appointed Chief of the Intelligence Division in the Philippines. His main task was to rebuild the country's security services.

On his return to the United States in 1948 Lansdale became a lecturer at the Strategic Intelligence School in Colorado. However, in 1950, Elpidio Quirino, the president of the Philippines, requested Lansdale's help in his fight against the communist insurrection taking place in his country.

In the early 1950s, Allen Dulles gave Lansdale $5-million to finance CIA operations against the Hukbalahap movement, the rural peasant farmers fighting for land-reform in the Philippines.

According to Sterling Seagrave Lansdale "was in and out of Tokyo on secret missions with a hand-picked team of Filipino assassins, assassinating leftists, liberals and progressives." CIA Director William Colby later commented: "Lansdale helped and perhaps created the best president the Philippines ever had...turned American policy away from support of French colonial rule in Vietnam to support of a non-Communist nationalist leader...he preached for Americans to support those willing to fight for themselves... He was one of the greatest spies in history... the stuff of legends."

In 1953 Lansdale was sent to Vietnam to advise the French in their struggle with the Vietminh. Dulles told President Dwight Eisenhower that he was sending one of his “best men”. The following year Lansdale and a team of twelve intelligence agents were sent to Saigon. The plan was to mount a propaganda campaign to persuade the Vietnamese people in the south not to vote for the communists in the forthcoming elections.

In the months that followed they distributed targeted documents that claimed the Vietminh and Chinese communists had entered South Vietnam and were killing innocent civilians. The Ho Chi Minh government was also accused of slaying thousands of political opponents in North Vietnam.

Colonel Lansdale also recruited mercenaries from the Philippines to carry out acts of sabotage in North Vietnam. This was unsuccessful and most of the mercenaries were arrested and put on trial in Hanoi. Finally, Lansdale set about training the South Vietnamese army (ARVN) in modem fighting methods. For it was coming clear that it was only a matter of time before the communists would resort to open warfare.

In 1955 Graham Greene published The Quiet American. The novel is set in Vietnam and involves the relationship between Thomas Fowler and Alden Pyle. Fowler is a veteran British journalist in his fifties, who has been covering the war in Vietnam for over two years. Pyle, the “Quiet American” of the title, is officially an aid worker, but is really employed by the CIA. It is believed that the Pyle character is partly based on that of Edward Lansdale.

Greene had worked for the British Secret Service during the Second World War. Although a fairly successful novelist at the time, Greene was also employed by The Times and Le Figaro as a journalist. Between 1951 to 1954 spent a long period of time in Saigon. In 1953 Lansdale became a CIA advisor on special counter-guerrilla operations to French forces against the Viet Minh.

While it is true that Graham Greene admitted that he never had the "misfortune to meet" Lansdale, the two men did know a lot about each other. Lansdale recalls that in 1954 he had dinner with Peg and Tilman Durdin at the Continental Hotel in Saigon. Greene was also there having a meal with several French officers. Lansdale claims that after he and the Durdins were leaving, Greene said something in French to his companions and the men began booing him.

Lansdale definitely thought that Pyle was based on him. He told Cecil B. Currey on 15th February, 1984: "Pyle was close to Trinh Minh Thé, the guerrilla leader, and also had a dog that went with him everywhere - and I was the only American close to Trinh Minh Thé and my poodle Pierre went everything with me."

In the book Pyle is sent to Vietnam by his government, ostensibly as a member of the American Economic Mission, but that assignment was only a cover for his real role as a CIA agent. According to one critic "Pyle was the embodiment of well-meaning American-style politics, and he blundered through the intrigue, treachery, and confusion of Vietnamese politics, leaving a trail of blood and suffering behind him." As Fowler points out in the novel, Pyle was attempting to "win the East for Democracy". However, according to Fowler, what the people of Vietnam really wanted was "enough rice" to eat. What is more: "They don't want to be shot at. They want one day to be much the same as another. They don't want our white skins around telling them what they want."

When the book was published in the United States in 1956 it was condemned as anti-American. Pyle (Lansdale) is portrayed as someone whose belief in the justice of American foreign policy allows him to ignore the appalling consequences of his actions. It was criticized by The New Yorker for portraying Americans as murderers.

The director, producer and screenwriter, Joseph L. Mankiewicz was chosen to make the film of The Quiet American. He visited Saigon in 1956 and was introduced to Edward Lansdale, whose cover was working at the International Rescue Committee’s office. The most controversial scene in the book is the bombing of a Saigon square in 1952 by a Vietnamese associate of Lansdale’s, General Trinh Minh Thé. In the novel, Greene suggests that Pyle/Lansdale, was behind the bombing. Lansdale suggested to Mankiewicz that the film should show that the bombing was “actually having been a Communist action”.

When he returned home Mankiewicz wrote to John O’Daniel, the chairman of the American Friends of Vietnam that he intended to completely change the anti-American attitude of Greene’s book. This included the casting of Second World War hero, Audie Murphy, as Alden Pyle.

In a letter that Edward Lansdale wrote to Ngo Dinh Diem he praised Mankiewicz’s treatment of the story as “an excellent change from Mr. Greene’s novel of despair” and “that it will help win more friends for you and Vietnam in many places in the world where it is shown."

As Hugh Wilford pointed out: “It was a brilliantly devious maneuver of postmodern literary complexity: by helping to rewrite a story featuring a character reputedly based on himself, Lansdale had transformed an anti-American tract into a cinematic apology for U.S. policy - and his own actions-in Vietnam.”

Graham Greene was furious with Mankiewicz’s treatment ofhis novel. "Far was it from my mind, when I wrote The Quiet American that the book would become a source of spiritual profit to one of the most corrupt governments in Southeast Asia."

In October, 1955, the South Vietnamese people were asked to choose between Bo Dai, the former Emperor of Vietnam, and Ngo Dinh Diem for the leadership of the country. Lansdale suggested that Diem should provide two ballot papers, red for Diem and green for Bao Dai. Lansdale hoped that the Vietnamese belief that red signified good luck whilst green indicated bad fortune, would help influence the result.

When the voters arrived at the polling stations they found Diem's supporters in attendance. One voter complained afterwards: "They told us to put the red ballot into envelopes and to throw the green ones into the wastebasket. A few people, faithful to Bao Dai, disobeyed. As soon as they left, the agents went after them, and roughed them up... They beat one of my relatives to pulp."

After the election Ngo Dinh Diem informed his American advisers that he had achieved 98.2 per cent of the vote. Lansdale warned him that these figures would not be believed and suggested that he published a figure of around 70 per cent. Diem refused and as the Americans predicted, the election undermined his authority.

Another task of Lansdale and his team was to promote the success of the rule of President Ngo Dinh Diem. Figures were produced that indicated that South Vietnam was undergoing an economic miracle. With the employment of $250 millions of aid per year from the United States and the clever manipulating of statistics, it was reported that economic production had increased dramatically.

Lansdale left Vietnam in 1957 and officially went to work for the Secretary of Defence in Washington. However, he was also employed as a senior officer in the Central Intelligence Agency. Posts held included: Deputy Assistant Secretary for Special Operations (1957-59), Staff Member of the President's Committee on Military Assistance (1959-61).

In March 1960, President Dwight Eisenhower of the United States approved a CIA plan to overthrow Fidel Castro. The plan involved a budget of $13 million to train "a paramilitary force outside Cuba for guerrilla action."

When President John F. Kennedy took office, Lansdale was appointed as Assistant Secretary of Defence for Special Operations. He argued that the CIA should work closely with exiles in Cuba, particularly those with middle-class professions, who had opposed Fulgencio Batista and had then become disillusioned with Fidel Castro because of his betrayal of the democratic process. Lansdale was also opposed to the Bay of Pigs operation because he knew that it would not trigger a popular uprising against Castro. Kennedy respected the advice of Lansdale and selected him to become project leader of Operation Mongoose.

Over 400 CIA officers were employed full-time on this project. Sidney Gottlieb of the CIA Technical Services Division was asked to come up with proposals that would undermine Castro's popularity with the Cuban people. Plans included a scheme to spray a television studio in which he was about to appear with an hallucinogenic drug and contaminating his shoes with thallium which they believed would cause the hair in his beard to fall out.

These schemes were rejected and instead Richard Bissell decided to arrange the assassination of Fidel Castro. In September 1960, Bissell and Allen W. Dulles, the director of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), initiated talks with two leading figures of the Mafia, Johnny Roselli and Sam Giancana. Later, other crime bosses such as Carlos Marcello, Santos Trafficante and Meyer Lansky became involved in this plot against Castro.

Robert Maheu, a veteran of CIA counter-espionage activities, was instructed to offer the Mafia $150,000 to kill Fidel Castro. The advantage of employing the Mafia for this work is that it provided CIA with a credible cover story. The Mafia were known to be angry with Castro for closing down their profitable brothels and casinos in Cuba. If the assassins were killed or captured the media would accept that the Mafia were working on their own.

The Federal Bureau of Investigation had to be brought into this plan as part of the deal involved protection against investigations against the Mafia in the United States. Castro was later to complain that there were twenty ClA-sponsered attempts on his life. Eventually Johnny Roselli and his friends became convinced that the Cuban revolution could not be reversed by simply removing its leader. However, they continued to play along with this CIA plot in order to prevent them being prosecuted for criminal offences committed in the United States.

Lansdale later claimed that John F. Kennedy asked him to draft a contingency plan to overthrow Fidel Castro. But he added that the idea had not been viable because it depended on recruiting Cuban exiles to generate an uprising in Cuba, something that he said was impossible.

In 1963 Kennedy asked Lansdale to concentrate on the situation in Vietnam. However, it was not long before Lansdale was in conflict with General Maxwell Taylor, who was the military representative to the president. Taylor took the view that the war could be won by military power. He argued in the summer of 1963 that 40,000 US troops could clean up the Vietminh threat in Vietnam and another 120,000 would be sufficient to cope with any possible North Vietnamese or Chinese intervention.

Lansdale disagreed with this viewpoint. He had spent years studying the way Mao Zedong had taken power in China. He often quoted Mao of telling his guerrillas: "Buy and sell fairly. Return everything borrowed. Indemnify everything damaged. Do not bathe in view of women. Do not rob personal belongings of captives." The purpose of such rules, according to Mao, was to create a good relationship between the army and its people. This was a strategy that had been adopted by the National Liberation Front. Lansdale believed that the US Army should adopt a similar approach. As Cecil B. Currey, the author of Edward Lansdale: The Unquiet American pointed out: "Lansdale was a dedicated anticommunist, conservative in his thoughts. Many people of like persuasion were neither as willing to study their enemy nor as open to adopting communist ideas to use a countervailing force. If for no other reason, the fact makes Lansdale stand out in bold relief to the majority of fellow military men who struggled on behalf of America in those intense years of the cold war."

Lansdale also argued against the overthrow of Ngo Dinh Diem. He told Robert McNamara that: "There's a constitution in place… Please don't destroy that when you're trying to change the government. Remember there's a vice president (Nguyen Ngoc Tho) who's been elected and is now holding office. If anything happens to the president, he should replace him. Try to keep something sustained."

It was these views that got him removed from office. The pressure to remove Lansdale came from General Curtis LeMay and General Victor Krulak and other senior members of the military. As a result it was decided to abolish his post as assistant to the secretary of defence. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal for counter-insurgency work and became consultant to the the Food for Peace programme.

Lansdale continued to argue against Lyndon Johnson's decision to try and use military power to win the Vietnam War. When General William Westmoreland argued that: "We're going to out-guerrilla the guerrilla and out-ambush the ambush… because we're smarter, we have greater mobility and fire-power, we have more endurance and more to fight for… And we've got more guts." Lansdale replied: "All actions in the war should be devised to attract and then make firm the allegiance of the people." He added "we label our fight as helping the Vietnamese maintain their freedom" but when "we bomb their villages, with horrendous collateral damage in terms of both civilian property and lives… it might well provoke a man of good will to ask, just what freedom of what Vietnamese are we helping to maintain?"

Lansdale quoted Robert Taber (The War of the Flea): "There is only one means of defeating an insurgent people who will not surrender, and that is extermination. There is only one way to control a territory that harbours resistance, and that is to turn it into a desert. Where these means cannot, for whatever reason, be used, the war is lost." Lansdale thought this was the situation in Vietnam and wrote to a friend that if the solution was to "kill every last person in the enemy ranks" then he was "not only morally opposed" to this strategy but knew it was "humanly impossible".

Lansdale added "No idea can be bombed or beaten to death. Military action alone is never enough." He pointed out that since 1945 the Vietminh had been willing to fight against the strength of both France and the United States in order to ensure success of their own. "Without a better idea, rebels will eventually win, for ideas are defeated only by better ideas."

Lansdale was anti-communist because he really believed in democracy. Lansdale had been arguing since 1956 that the best way of dealing with the National Liberation Front was to introduce free elections that included the rights of Chams, Khmers, Montagnards and other minorities to participate in voting. Lansdale said that he went into Vietnam as Tom Paine would have done. He was found of quoting Paine as saying: "Where liberty dwells not, there is my country."

He also distanced himself from the Freedom Studies Center of the Institute for American Strategy when he discovered it was being run by the John Birch Society. He told a friend: "I refused to have anything more to do with it… That isn't what our country is all about." Lansdale considered himself a "conservative moderate" who was tolerant of all minorities.

Lansdale continued to advocate a non-military solution to Vietnam and in 1965, under orders from President Lyndon B. Johnson, the new US ambassador in Saigon, Henry Cabot Lodge, put Lansdale in charge of the "pacification program" in the country. As Newsweek reported: " Lansdale is expected to push hard for a greater effort on the political and economic fronts of the war, while opposing the recent trend bombing and the burning of villages."

One of those who served under him in this job was Daniel Ellsberg. He liked Lansdale because of his commitment to democracy. Ellsberg also agreed with Lansdale that the pacification program should be run by the Vietnamese. He argued that unless it was a Vietnam project it would never work. Lansdale knew that there was a deep xenophobia among Vietnamese. However, as he pointed out, he believed "Lyndon Johnson would have been just as xenophobic if Canadians or British or the French moved in force into the United States and took charge of his dreams for a great Society, told him what to do, and spread out by thousands throughout the nation to see that it got done."

In February 1966 Lansdale was removed from his position in control of the pacification program. However, instead of giving the job to a Vietnamese, William Porter, was given the post. Lansdale was now appointed as a senior liaison officer, with no specific responsibilities.

Unlike most Americans in Vietnam, Lansdale believed it was essential for Vietnamese leaders to claim credit for any changes and reforms. His attitude aroused antagonism in the hearts of many within the U.S. bureaucracy who didn't like the idea of allowing others to receive credit for successful programs – although they did not object to blaming Vietnamese leaders for projects that failed.

Most importantly, Lansdale thought that the military should be careful to avoid causing civilian casualties. As his biographer, Cecil B. Currey pointed out: " Lansdale was primarily concerned about the welfare of people. Such a stance made him anathema to those more concerned about search and destroy missions, agent orange, free fire zones, harassing and interdicting fires, and body counts."

According to Lansdale "we lost the war at the Tet offensive". The reason for this was that after this defeat American commanders lost the ability to discriminate between friend and foe. All Vietnamese were now "gooks". Lansdale complained that commanders resorted more and more on artillery barrages that killed thousands of civilians. He told a friend that: "I don't believe this is a government that can win the hearts and minds of the people." Lansdale resigned and returned to the United States in June 1968.

Lansdale retired in 1968 and his book, The Midst of Wars, was published in 1972. Lansdale argued that the United States could still retain control of third-world nations by exporting ''the American way'' through a blend of economic aid and efforts at ''winning the hearts and the minds of the people.''

Edward Lansdale died in McLean, Virginia, on 23rd February, 1987.

Primary Sources

(1) Cecil B. Currey, Edward Lansdale: The Unquiet America (1988)

Lansdale was a dedicated anticommunist, conservative in his thoughts. Many people of like persuasion were neither as willing to study their enemy nor as open to adopting communist ideas to use a countervailing force. If for no other reason, the fact makes Lansdale stand out in bold relief to the majority of fellow military men who struggled on behalf of America in those intense years of the cold war.

(2) Edward Lansdale, interview with Cecil B. Currey (15th February, 1984)

Graham Greene once told someone that he definitely did not have me in mind when he created the character Alden Pyle. I sure hope not... On the other hand Pyle was close to Trinh Minh Thé, the guerrilla leader, and also had a dog that went with him everywhere - and I was the only American close to Trinh Minh Thé and my poodle Pierre went everything with me."

(3) L. Fletcher Prouty, letter to Jim Garrison (6th March, 1990)

It is amazing how things work, I am at home recuperating from a major back operation (to regain my ability to walk); so I was tossing around in bed last night...not too comfortable...and I began to think of Garrison. I thought, "I have got to write Jim a letter detailing how I believe the whole job was done."

By another coincidence I had received a fine set of twenty photos from the Sprague collection in Springfield, Mass. As the odds would have it, he is now living just around the corner here in Alexandria. Why not? Lansdale lived here, Fensterwald lives here, Ford used to live here. Quite a community.

I was studying those photos. One of them is the "Tramps" picture that appears in your book. It is glossy and clear. Lansdale is so clearly identifiable. Why, Lansdale in Dallas? The others don't matter, they are nothing but actors and not gunmen but they are interesting. Others who knew Lansdale as well as I did, have said the same thing, "That's him and what's he doing there?"

As I was reading the paper the Federal Express man came with a book from Jim, that unusual "Lansdale" book. A terrible biography. There could be a great biography about Lansdale. He's no angel; but he is worth a good biography. Currey, a paid hack, did the job. His employers ought to have let him do it right.

I had known Ed since 1952 in the Philippines. I used to fly there regularly with my MATS Heavy Transport Squadron. As a matter of fact, in those days we used to fly wounded men, who were recuperating, from hospitals in Japan to Saigon for R&R on the beaches of Cap St Jacque. That was 1952-1953. Saigon was the Paris of the Orient. And Lansdale was "King Maker" of the Philippines. We always went by way of Manila. I met his team.

He had arrived in Manila in Sept 1945, after the war was over, for a while. He had been sent back there in 1950 by the CIA(OPC) to create a new leader of the Philippines and to get rid of Querino. Sort of like the Marcos deal, or the Noriega operation. Lansdale did it better. I have overthrown a government but I didn't splash it all around like Reagan and Bush have done. Now, who sent him there?

Who sent him there in 1950 (Truman era) to do a job that was not done until 1953 (Ike era)? From 1950 to Feb. 1953 the Director of Central Intelligence was Eisenhower's old Chief of Staff, Gen Walter Bedell Smith. Smith had been Ambassador to Moscow from 1946 to 1949. The lesser guys in the CIA at the time were Allen Dulles, who was Deputy Director Central Intelligence from Aug. 1951 to Feb. 1953. Frank Wisner became the Deputy Director, Plans (Clandestine Activities) when Dulles became DDCI. Lansdale had to have received his orders from among these four men: Truman, Smith, Dulles, and Wisner. Of course the Sec State could have had some input...i.e. Acheson. Who wanted Querino out, that badly? Who wanted HUKS there?

In Jan 1953 Eisenhower arrived. John Foster Dulles was at State and Gen Smith his Deputy. Allen Dulles was the DCI and General Cabel his deputy. None of them changed Lansdale's prior orders to "get" Querino. Lansdale operated with abandon in the Philippines. The Ambassador and the CIA Station Chief, George Aurell, did not know what he was doing. They believed he was some sort of kook Air Force Officer there...a role Lansdale played to the hilt. Magsaysay became President, Dec 30, 1953.

With all of this on the record, and a lot more, this guy Currey comes out of the blue with this purported "Biography". I knew Ed well enough and long enough to know that he was a classic chameleon. He would tell the truth sparingly and he would fabricate a lot. Still, I can not believe that he told Currey the things Currey writes. Why would Lansdale want Currey to perpetuate such out and out bullshit about him? Can't be. This is a terribly fabricated book. It's not even true about me. I believe that this book was ordered and delineated by the CIA.

At least I know the truth about myself and about Gen. Krulak. Currey libels us terribly. In fact it may be Krulak who caused the book to be taken off the shelves. Krulak and his Copley Press cohorts have the power to get that done, and I encouraged them to do just that when it first came out. Krulak was mad!

Ed told me many a time how he operated in the Philippines. He said, "All I had was a blank checkbook signed by the U.S. government". He made friends with many influential Filipinos. I have met Johnny Orendain and Col Valeriano, among others, in Manila with Lansdale. He became acquainted with the wealthiest Filipino of them all, Soriano. Currey never even mentions him. Soriano set up Philippine Airlines and owned the big San Miguel beer company, among other things. Key man in Asia.

Lansdale's greatest strategy was to create the "HUKS" as the enemy and to make Magsaysay the "Huk Killer." He would take Magsaysay's battalion out into a "Huk" infested area. He would use movies and "battlefield" sound systems, i.e. fireworks to scare the poor natives. Then one-half of Magsaysay's battalion, dressed as natives, would "attack" the village at night. They'd fire into the air and burn some shacks. In the morning the other half, in uniform, would attack and "capture" the "Huks". They would bind them up in front of the natives who crept back from the forests, and even have a "firing" squad "kill" some of them. Then they would have Magsaysay make a big speech to the people and the whole battalion would roll down the road to have breakfast together somewhere...ready for the next "show".

Ed would always see that someone had arranged to have newsmen and camera men there and Magsaysay soon became a national hero. This was a tough game and Ed bragged that a lot of people were killed; but in the end Magsaysay became the "elected" President and Querino was ousted "legally."

This formula endeared Ed to Allen Dulles. In 1954 Dulles established the Saigon Military Mission in Vietnam...counter to Eisenhower's orders. He had the French accept Lansdale as its chief. This mission was not in Saigon. It was not military, and its job was subversion in Vietnam. Its biggest job was that it got more than 1,100,000 northern Vietnamese to move south. 660,000 by U.S.Navy ships and the rest by CIA airline planes. These 1,100,000 north Vietnamese became the "subversive" element in South Vietnam and the principal cause of the warmaking. Lansdale and his cronies (Bohanon, Arundel, Phillips, Hand, Conein and many others) did all that using the same check book. I was with them many times during 1954. All Malthuseanism.

I have heard him brag about capturing random Vietnamese and putting them in a Helicopter. Then they would work on them to make them "confess" to being Viet Minh. When they would not, they would toss them out of the chopper, one after the other, until the last ones talked. This was Ed's idea of fun...as related to me many times. Then Dulles, Adm. Radford and Cardinal Spellman set up Ngo Dinh Diem. He and his brother, Nhu, became Lansdale proteges.

At about 1957 Lansdale was brought back to Washington and assigned to Air Force Headquarters in a Plans office near mine. He was a fish out of water. He didn't know Air Force people and Air Force ways. After about six months of that, Dulles got the Office of Special Operations under General Erskine to ask for Lansdale to work for the Secretary of Defense. Erskine was man enough to control him.

By 1960 Erskine had me head the Air Force shop there. He had an Army shop and a Navy shop and we were responsible for all CIA relationships as well as for the National Security Agency. Ed was still out of his element because he did not know the services; but the CIA sent work his way.

Then in the Fall of 1960 something happened that fired him up. Kennedy was elected over Nixon. Right away Lansdale figured out what he was going to do with the new President. Overnight he left for Saigon to see Diem and to set up a deal that would make him, Lansdale, Ambassador to Vietnam. He had me buy a "Father of his Country" gift for Diem...$700.00.

I can't repeat all of this but you should get a copy of the Gravel edition, 5 Vol.'s, of the Pentagon Papers and read it. The Lansdale accounts are quite good and reasonably accurate.

Ed came back just before the Inauguration and was brought into the White House for a long presentation to Kennedy about Vietnam. Kennedy was taken by it and promised he would have Lansdale back in Vietnam "in a high office". Ed told us in OSO he had the Ambassadorship sewed up. He lived for that job.

He had not reckoned with some of JFK's inner staff, George Ball, etc. Finally the whole thing turned around and month by month Lansdale's star sank over the horizon. Erskine retired and his whole shop was scattered. The Navy men went back to the navy as did the Army folks. Gen Wheeler in the JCS asked to have me assigned to the Joint Staff. This wiped out the whole Erskine (Office of Special Operations) office. It was comical. There was Lansdale up there all by himself with no office and no one else. He boiled and he blamed it on Kennedy for not giving him the "promised" Ambassadorship to let him "save" Vietnam.

Then with the failure of the Bay of Pigs, caused by that phone call to cancel the air strikes by McGeorge Bundy, the military was given the job of reconstituting some sort of Anti-Castro operation. It was headed by an Army Colonel; but somehow Lansdale (most likely CIA influence) got put into the plans for Operation Mongoose...to get Castro...ostensibly.

The U.S. Army has a think-tank at American University. It was called "Operation Camelot". This is where the "Camelot" concept came from. It was anti-JFK's Vietnam strategy. The men running it were Lansdale types, Special Forces background. "Camelot" was King Arthur and Knights of the Round Table: not JFK...then.

Through 1962 and 1963 Mongoose and "Camelot" became strong and silent organizations dedicated to countering JFK. Mongoose had access to the CIA's best "hit men" in the business and a lot of "strike" capability. Lansdale had many old friends in the media business such as Joe Alsop, Henry Luce among others. With this background and with his poisoned motivation I am positive that he got collateral orders to manage the Dallas event under the guise of "getting" Castro. It is so simple at that level. A nod from the right place, source immaterial, and the job's done.

The "hit" is the easy part. The "escape" must be quick and professional. The cover-up and the scenario are the big jobs. They more than anything else prove the Lansdale mastery.

Lansdale was a master writer and planner. He was a great "scenario" guy. It still have a lot of his personally typed material in my files. I am certain that he was behind the elaborate plan and mostly the intricate and enduring cover-up. Given a little help from friends at PEPSICO he could easily have gotten Nixon into Dallas, for "orientation': and LBJ in the cavalcade at the same time, contrary to Secret Service policy.

He knew the "Protection" units and the "Secret Service", who was needed and who wasn't. Those were routine calls for him, and they would have believed him. Cabell could handle the police.

The "hit men" were from CIA overseas sources, for instance, from the "Camp near Athena, Greece. They are trained, stateless, and ready to go at any time. They ask no questions: speak to no one. They are simply told what to do, when and where. Then they are told how they will be removed and protected. After all, they work for the U.S. Government. The "Tramps" were actors doing the job of cover-up. The hit men are just pros. They do the job for the CIA anywhere. They are impersonal. They get paid. They get protected, and they have enough experience to "blackmail" anyone, if anyone ever turns on them...just like Drug agents. The job was clean, quick and neat. No ripples.

The whole story of the POWER of the Cover-up comes down to a few points. There has never been a Grand Jury and trial in Texas. Without a trial there can be nothing. Without a trial it does no good for researchers to dig up data. It has no place to go and what the researchers reveal just helps make the cover-up tighter, or they eliminate that evidence and the researcher.

The first man LBJ met with on Nov 29th, after he had cleared the foreign dignitaries out of Washington was Waggoner Carr, Atty Gen'l, Texas to tell him, "No trial in Texas...ever."

The next man he met, also on Nov 29th, was J. Edgar Hoover. The first question LBJ asked his old "19 year" neighbor in DC was "Were THEY shooting at me?" LBJ thought that THEY had been shooting at him also as they shot at his friend John Connally. Note that he asked, "Were THEY shooting at me?" LBJ knew there were several hitmen. That's the ultimate clue...THEY.

The Connallys said the same thing...THEY. Not Oswald.

Then came the heavily loaded press releases about Oswald all written before the deal and released actually before LHO had ever been charged with the crime. I bought the first newspaper EXTRA on the streets of Christchurch, New Zealand with the whole LHO story in that first news...photos and columns of it before the police in Dallas had yet to charge him with that crime. All this canned material about LHO was flashed around the world.

Lansdale and his Time-Life and other media friends, with Valenti in Hollywood, have been doing that cover-up since Nov 1963. Even the deMorenschildt story enhances all of this. In deM's personal telephone/address notebook he had the name of an Air Force Colonel friend of mine, Howard Burrus. Burrus was always deep in intelligence. He had been in one of the most sensitive Attache spots in Europe...Switzerland. He was a close friend of another Air Force Colonel and Attache, Godfrey McHugh, who used to date Jackie Bouvier. DeM had Burrus listed under a DC telephone number and on that same telephone number he had "L.B.Johnson, Congressman." Quite a connection. Why...from the Fifties yet.?

Godfrey McHugh was the Air Force Attache in Paris. Another most important job. I knew him well, and I transferred his former Ass't Attache to my office in the Pentagon. This gave me access to a lot of information I wanted in the Fifties. This is how I learned that McHugh's long-time special "date" was the fair Jacqueline...yes, the same Jackie Bouvier. Sen. Kennedy met Jackie in Paris when he was on a trip. At that time JFK was dating a beautiful SAS Airline Stewardess who was the date of that Ass't Attache who came to my office. JFK dumped her and stole Jackie away from McHugh. Leaves McHugh happy????

At the JFK Inaugural Ball who should be there but the SAS stewardess, Jackie--of course, and Col Godfrey McHugh. JFK made McHugh a General and made him his "Military Advisor" in the White House where he was near Jackie while JFK was doing all that official travelling connected with his office AND other special interests. Who recommended McHugh for the job?

General McHugh was in Dallas and was on Air Force One, with Jackie, on the flight back to Washington..as was Jack Valenti. Why was LBJ's old cohort there at that time and why was he on Air Force One? He is now the Movie Czar. Why in Dallas?

See how carefully all of this is interwoven. Burrus is now a very wealthy man in Washington. I have lost track of McHugh. And Jackie is doing well. All in the Lansdale--deM shadows.

One of Lansdale's special "black" intelligence associates in the Pentagon was Dorothy Matlack of U.S. Army Intelligence. How does it happen that when deM. flew from Haiti to testify, he was met at the National Airport by Dorothy?

The Lansdale story is endless. What people do not do is study the entire environment of his strange career. For example: the most important part of my book, "The Secret Team", is not something that I wrote. It is Appendix III under the title, "Training Under The Mutual Security Program". This is a most important bit of material. It tells more about the period 1963 to 1990 than anything. I fought to have it included verbatim in the book. This material was the work of Lansdale and his crony General Dick Stillwell. Anyone interested in the "JFK Coup d'Etat" ought to know it by heart.

I believe this document tells why the Coup took place. It was to reverse the sudden JFK re-orientation of the U.S. Government from Asia to Europe, in keeping with plans made in 1943 at Cairo and Teheran by T.V. Soong and his Asian masterminds. Lansdale and Stillwell were long-time "Asia hands" as were Gen Erskine, Adm Radford, Cardinal Spellman, Henry Luce and so many others.

In October 1963, JFK had just signalled this reversal, to Europe, when he published National Security Action Memorandum #263 saying...among other things...that he was taking 1000 troops home from Vietnam by Christmas 1963 and ALL AMERICANS out of Vietnam by the end of 1965. That cost him his life.

JFK came to that "Pro-Europe" conclusion in the Summer of 1963 and sent Gen Krulak to Vietnam for advance work. Kurlak and I (with others) wrote that long "Taylor-McNamara" Report of their "Visit to Vietnam" (obviously they did not write, illustrate and bind it as they traveled). Krulak got his information daily in the White House. We simply wrote it. That led to NSAM #263. This same Trip Report is Document #142 and appears on page 751 to 766 of Vol. II of the Gravel Edition of the Pentagon Papers. NSAM #263 appears on pages 769-770 (It makes the Report official). This major Report and NSAM indicated an enormous shift in the orientation of U.S. Foreign Policy from Asia back to Europe. JFK was much more Europe- oriented, as was his father, than pro-Asia. This position was anathema to the Asia-born Luces, etc.

There is the story from an insider. I sat in the same office with Lansdale, (OSO of OSD) for years. I listened to him in Manila and read his flurry of notes from 1952 to 1964. I know all this stuff, and much more. I could write ten books. I send this to you because I believe you are one of the most sincere of the "true researchers". You may do with it as you please. I know you will do it right. I may give copies of this to certain other people of our persuasion. (Years ago I told this to Mae Brussell on the promise she would hold it. She did.)

Now you can see why I have always said that identification of the "Tramps" was unnecessary, i.e. they are actors. The first time I saw that picture I saw the man I knew and I realized why he was there. He caused the political world to spin on its axis. Now, back to recuperating.

(4) Cecil B. Currey, Edward Lansdale: The Unquiet America (1988)

In August 1962, SGA brought intelligence collection to an end. On 10 August, members of SGA met in the office of Dean Rusk, the secretary of state. Others who gathered that day included McNamara, John A. McCone, CIA; Edward R. Murrow, director of USIA; McGeorge Bundy, Kennedy's national security adviser; Edward Lansdale; and others. They met to decide on the next phase of Mongoose. Lansdale suggested they now enter Course B, a plan to "exert all possible diplomatic, economic, psychological and other overt pressures to overthrow the Castro-communist regime, without overt employment of U.S. military." Lansdale told his fellow SGA members, "We want boom and bang on the island.

Those present that day also discussed assassinating Castro. Given the Kennedys' fixation on getting rid of him and the activities of Harvey's Task Force W, it is difficult to believe that no such conversations occurred earlier. But that day is the first for which specific evidence exists. John McCone later recalled that it was one of the topics, although he claimed that he personally opposed any such action. He thought it may have been McNamara who brought it up, although the secretary of defense later claimed he could not recall any talk of assassination. Walter Elder, McCone's executive assistant, was in his boss's office when McCone telephoned McNamara shortly after the meeting broke up. Elder remembered that McCone told McNamara that "the subject you just brought up. I think it is highly improper. I do not think it should be discussed. It is not an action that should ever be condoned. It is not proper for us to discuss and I intend to have it expunged from the record."

Not knowing McCone's reluctance to have anything left on paper, Lansdale prepared an action memorandum, dated 13 August, which called for the preparation of contingency plans for "Intelligence, Political (including liquidation of leaders), Economic (sabotage, limited deception) and Paramilitary. " He sent copies to William Harvey, to the State Department's Robert Hurwith, to General Benjamin Harris of the Defense Department, and to Donald Wilson, USIA.

Thirteen years later, the Church Committee of the United States Senate gave a long, hard look at allegations that the government of this country had been involved in various assassination attempts on leaders in other nations. The principals who were involved in Mongoose were called upon to give testimony. There was suddenly a veritable implosion of recall and memory. Few could remember anything pertinent, and those who did could do so only vaguely and with uncertainty.

William Harvey had died by that time so it was acceptable to remember his efforts at planning Castro's assassination. When asked if Harvey kept him advised of what he was doing - the CIA man mounted at least eight different attempts on Castro's life - Lansdale insisted he never knew any details. "It would," he recalled, "have been highly unusual for me to know." Lansdale testified before the Church Committee that "I had no knowledge of such a thing. I know of no order or permission for such a thing and I was given no information at all that such a thing was going on by people who I have now learned were involved with it."

As a matter of fact, it would have been "highly unusual" had he not known what was planned, given his grasp of detail, his tight control over Task Force W, and his insistence on staying on top of current activity. Yet when grilled by the Church Committee, Lansdale insisted that when the subject was raised on 10 August, "the consensus was ... hell no on this and there was a very violent reaction."

If that was the decision at the 10 August meeting, why then had Lansdale gone ahead to call for "liquidation" of Cuban leaders? He testified that "I thought it would be a possibility someplace down the road in which there would be some possible need to take action such as that [assassination]." His position was simple and straightforward. Every means should be explored for removing the threat posed by Fidel Castro. For that reason he instructed Harvey to develop contingency plans in order to learn if the United States had the capability for "wet" actions.

Why had he circulated his memorandum? Lansdale waffled. "I don't recall that thoroughly. I don't remember the reasons why I would." Was it not his understanding that assassination efforts had already been vetoed at the 10 August meeting? "I guess it is, yes," the general replied. "The way you put it to me now has me baffled about why I did it. I don't know." Lansdale added another disclaimer in his plea of innocence. Although he "had doubts" that assassination was a "useful action, and [was] one I had never employed in the past, during work in coping with revolutions, and I had considerable doubts as to its utility ... I was trying to be very pragmatic." As a good soldier, he admitted that any responsibility must have been his own. General Benjamin Harris was a little more open. He testified that such activities are "not out of the ordinary in terms of contingency planning... it's one of the things you look at."

Harris was correct. It was not shameful for the Special Group Augmented to look into the possibility of assassination. In a committee composed of members of the highest level of government, it would rather be shameful had they not explored the subject, assigned as they were to promote the destabilization of Cuba. Whether destabilization itself was a proper subject for American attention is an altogether different question that could be fruitfully considered. That was not, however, the assignment given those men during 1962 by the American president!

When Harvey received Lansdale's memorandum, his first thought was of the danger of leaving such records for future investigative committees. He immediately called Lansdale's office and pointed out "the inadmissibility and stupidity of putting this type of comment in writing in such documents." He further added that CIA "would write no document pertaining to this and would participate in no open meeting discussing it." On 14 August, Harvey wrote Helms stating that although Secretary McNamara had brought up the topic of assassination and Lansdale had written a memorandum about it, liquidation of foreign leaders was not an appropriate subject for inclusion in official records and he further insisted the offending words be deleted from both Lansdale's memorandum and any minutes of the meeting.

Lansdale later recalled only one additional contact with Harvey. He had one brief conversation with the CIA agent after the 10 August meeting. At that time Harvey stated "he would look into it [the assassination of Castro and] see about developing some plans." That, Lansdale insisted, was the last he ever heard about assassinations.

(5) Daniel Ellsberg, interview with Cecil B. Currey (10th May 1967)

The French saw their mission civilatrice as bringing French culture, language, and history to the world. The British saw themselves as conferring the gift of administration, law, and order. Lansdale ... was pretty much an imperialist in the mold of the British except in his case... it was [to bring] democracy. He did think it was in the interest of the people he was working with, the Filipinos, the Vietnamese. At the same time he believed it was very much in their interest to be within the sphere of American influence... that our interest was to be served... by fostering a kind of nationalism and a relative independence which, however, would need American aid and influence but would be independent. It was a way of extending and ensuring a sphere of American influence for the good of America but also for the good of (other) people and against communism, which he despised.

(6) Lalo J. Gastriani, Fair Play Magazine, The Strange Death of Dorothy Hunt (November, 1994)

In the latest issue of Steam Shovel Press in an article by photo analyst Jack White, L. Fletcher Prouty describes one of several known Tramp photos. This particular photo shows the tramps being escorted along a service entrance to the TSBD wall comprised of two high chain-link gates with large diamond-shapes in the center of each. The tramps are facing the camera and a man is seen walking in the opposite direction, back to the camera. Prouty believes that the man walking away from the camera is Edward Lansdale. Lansdale, a planner with the Air Force Directorate and then the CIA-affiliated Office of Special Operations, worked closely with E. Howard Hunt. Lansdale's specialty, according to Prouty, who claims to have also worked closely with him, was staging real-time covers, diversions, and the general "smoke screens" under which assassinations took place. When asked to explain, Prouty alleges that it was Lansdale's job to provide "actors", and "screenplays" for certain black operations deployed by the covert operatives.

(7) Leroy Fletcher Prouty, An Introduction to the Assassination Business (1975)

Assassination is big business. It is the business of the CIA and any other power that can pay for the "hit" and control the assured getaway. The CIA brags that its operations in Iran in 1953 led to the pro-Western attitude of that important country. The CIA also takes credit for what it calls the "perfect job" in Guatemala. Both successes were achieved by assassination. What is this assassination business and how does it work?

In most countries there is little or no provision for change of political power. Therefore the strongman stays in power until he dies or until he is removed by a coup d'etat - which often means by assassination...

The CIA has many gadgets in its arsenal and has spent years training thousands of people how to use them. Some of these people, working perhaps for purposes and interests other than the CIA's, use these items to carry out burglaries, assassinations, and other unlawful activities - with or without the blessing of the CIA.

(8) Edward Lansdale, quoted by Cecil B. Currey in his book Edward Lansdale: The Unquiet American (1998)

I continue to be surprised to find Fletcher Prouty quoted as an authority. He was my "cross to bear" before Dan Ellsberg came along. Fletch is the one who blandly told the London Times that I'd invented the Huk Rebellion, hired a few actors in Manila, bussed them out to Pampanga, and staged the whole thing as press agentry to get RM (Magsaysay) elected. He was a good pilot of prop-driven aircraft, but had such a heavy dose of paranoia about CIA when he was on my staff that I kicked him back to the Air Force. He was one of those who thought I was secretly running the Agency from the Pentagon, despite all the proof otherwise.

(9) Eric Pace, The New York Times (24th February, 1987)

Edward G. Lansdale, an Air Force officer whose influential theories of counterinsurgent warfare proved successful in the Philippines after World War II but failed to bring victory in South Vietnam, died yesterday at his home in McLean, Va. He was 79 years old and had a heart ailment.

A dashing Californian, Mr. Lansdale is widely thought to have been the model for characters in two novels involving guerrilla warfare in Southeast Asia: ''The Quiet American'' by Graham Greene and ''The Ugly American'' by Eugene Burdick and William J. Lederer. He retired from the Air Force as a major general in 1963.

As an adviser in the newly independent Philippines in the late 1940's and early 1950's the future general came to wield great influence in operations by the Philippine leader Ramon Magsaysay against the Communist-dominated Hukbalahap rebellion. Under the leadership of Mr. Magsaysay, who was elected President while the struggle was going on, the operations succeeded.

It was in the Philippines that General Lansdale framed his basic theory, that Communist revolution was best confronted by democratic revolution. He came to advocate a four-sided campaign, with social, economic and political aspects as well as purely military operations. He put much emphasis on what came to be called civic-action programs to undermine Filipinos' backing for the Huks.

Looking back on what he learned in Asia, he once said: ''The Communists strive to split the people away from the Government and gain control over a decisive number of the population. The sure defense against this strategy is to have the citizenry and the Government so closely bound together that they are unsplittable.''

With that victory behind him, General Lansdale initially commanded great respect in the 1960's as an adviser to South Vietnamese and United States military leaders, and to Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge.

But his efforts to generate popular support for the embattled Saigon Government, at a time when the United States military role in Vietnam remained limited, failed to forestall an escalation of the insurgency to full-scale conventional warfare. Intellectual Direction

Early in the war, General Lansdale was considered to be the individual who provided the intellectual direction to the counterinsurgency and nation-building efforts. But he became less significant when the conflict left the counterinsurgency phase and became a more conventional war.

(10) Georgie Anne Geyer, Washington Monthly (June, 1989)

Who was Lansdale? To Graham Greene, he was Alden Pyle, "The Quiet American," a classic American innocent, not in Paris but in the poisoned, unfinished trouble spots of the world, nothing more than a CIA agent with "an unmistakably young and unused face." To Jean Larteguy, he was Colonel Lionel Teryman, "Le Male Jaune," a tough, brutal new American midwest version of Lawrence of Arabia. To the American writers William Lederer and Eugene Barnum Hillandale, "The Ugly American," practically the only American who understood how to mold with original hands the real and fractious world of new decolonized countries. To his brother, Benjamin Carroll Lansdale, he was always a "revolutionary." Quixotically and finally, Oliver North, totally unlike Lansdale in any sense of realism or proportion, looked upon himself as "Lansdalian"...

Lansdale was no angel. He took an important part in the CIA's "Operation Mongoose" to assassinate Cuban leader Fidel Castro. He strangely went against his own most treasured rules in Vietnam, when he was trying desperately to build support for Diem, by bribing generals of the many sects in Vietnam to bring their men behind Diem. In his own book, he then lied about this, an unpalatable act that was later revealed in the Pentagon Papers. And yet he knew things and he represented ideas and possibilities that were so far beyond the rigid and stratified - and, as it turned out, tragically unsuccessful - military thinking of his time that he remains a lone and original operational giant of modern warfare and America's role in it.

As Lansdale moved toward his death in 1987, he tried to call America to the real world of irregular conflict by recalling Continental troops at Valley Forge, officers and men under American guerilla leaders like Marion or Greene. He talked of the motivation of modern insurgent troops, of the use of propaganda. When Richard Nixon, who respected Lansdale, asked him in 1984 for some of his brief thoughts about modern wars, Lansdale wrote that "conventional operations are more apt to widen the problem or to be more cosmetic than a cure." The people were the true battleground of war and "whoever wins them, wins the war."

(11) Review of Edward Lansdale's Cold War (2004)

A cultural biography of a legendary Cold War figure; The man widely believed to have been the model for Alden Pyle in Graham Greene's The Quiet American, Edward G. Lansdale (1908-1987) was a Cold War celebrity. A former advertising executive turned undercover CIA agent, he was credited during the 1950s with almost single-handedly preventing a communist takeover of the Philippines and with helping to install Ngo Dinh Diem as president of the American-backed government of South Vietnam. Adding to his notoriety, during the Kennedy administration Lansdale was put in charge of Operation Mongoose, the covert plot to overthrow the government of Cuba's Fidel Castro by assassination or other means. In this book, Jonathan Nashel reexamines Lansdale's role as an agent of American Cold War foreign policy and takes into account both his actual activities and the myths that grew to surround him. In contrast to previous portraits, which tend to depict Lansdale either as the incarnation of U.S. imperialist ambitions or as a farsighted patriot dedicated to the spread of democracy abroad, Nashel offers a more complex and nuanced interpretation. At times we see Lansdale as the arrogant "ugly American," full of confidence that he has every right to make the world in his own image and utterly blind to his own cultural condescension. This is the Lansdale who would use any conceivable gimmick to serve U.S. aims, from rigging elections to sugaring communist gas tanks. Elsewhere, however, he seems genuinely respectful of the cultures he encounters, open to differences and new possibilities, and willing to tailor American interests to Third World needs. Rather than attempting to reconcile these apparently contradictory images of Lansdale, Nashel explores the ways in which they reflected a broader tension within the culture of Cold War America. The result is less a conventional biography than an analysis of the world in which Lansdale operated and the particular historical forces that shaped him - from the imperatives of anticommunist ideology and the assumptions of modernization theory to the techniques of advertising and the insights of anthropology.

(12) Andrew J. Rotter, Diplomatic History (2005)

The authorized biography of Lansdale is Cecil Currey's Edward Lansdale: The Unquiet American, published in 1988. Currey had previously written a book critical of the performance of the U.S. military command in Vietnam, and in it he had quoted approvingly Lansdale's lament that the United States had failed in Vietnam despite its use of "overwhelming amounts of men, money, and material"; the implication was that counterinsurgency, including greater and more sympathetic contact with the Vietnamese people, would have been a better strategy. If not quite hagiographic, Currey's treatment of Lansdale was, as Nashel puts it, "adulatory" (p. 3). (Nashel mentions having found a poignant photograph of Currey pushing a wheelchair-bound Lansdale through Disneyworld late in Lansdale's life.) The other key source on Lansdale was Lansdale himself. His memoir, In the Midst of Wars, was published in 1972. Reviewers at the time pointed out that Lansdale had omitted some salient facts about his career, such as his lengthy employment by the CIA. However, the book was full of stories about Lansdale's exploits in the Philippines and Vietnam, disarmingly modest accounts of how he helped Ramon Magsaysay take charge in the Philippines, how he had tried to put some spine into South Vietnamese leader Ngo Dinh Diem and conducted psychological warfare against Diem's enemies in the North, and, most gleefully, how he had frustrated French authorities in their efforts to keep control of some portion of their Indochina colony during the mid-1950s. The memoir was written in the style of an adventure novel, as Nashel notes. It was skillful most of all in its ability to conceal the truth by dint of its seeming candor: Lansdale made himself sound so mischievous that it was impossible to believe that he was not telling the whole story. Readers charmed by his tales, disarmed by his humor and playfulness and mildly confessional tone, were not likely to ask whether there was anything dirtier he was up to, or to question his assumptions at all.

Nashel is hardly unsympathetic to Lansdale, though at times he seems appalled or amused by him. Each of his chapters treats a different facet of Lansdale's identity. Nashel first describes Lansdale as an advertising man, as indeed he was for a time during the 1930s and 1940s. Lansdale wrote ads for food products and blue jeans. He would later advertise democracy and modernity, and use an ad-man's images and slogans to undercut the appeal of the Huks in the Philippines and the Viet Minh in Vietnam. He communicated not only through language but by using gestures, friendly touches, and slaps on the back; he did not speak Tagalog or Vietnamese but never felt burdened by this, for he knew, he said, how to gain a man's confidence by acting confidential. As an advocate for consumerism, Lansdale sold Asians the American dream, or tried to. He was also, of course, a spy. The details of Lansdale's work for the CIA remain classified - when Lansdale's papers appeared at the Hoover Institution in the early 1980s, agents turned up and carted off to Washington all the documents that revealed his connection to the agency - and Lansdale appreciated what Nashel rightly terms "the power of secrets" (p. 77) to manipulate people. Lansdale's loathing of communism and his ad-man's understanding of the importance of communication made him the consummate secret agent, even as he enjoyed pretending that he was no such thing.

(13) Sterling Seagrave, Edward Lansdale (14th November, 2008)

It is an inescapable fact that from the beginning of the US occupation of Japan, General MacArthur, President Truman, John Foster Dulles, and others, knew all about the stolen treasure in Japan and the continuing extraordinary wealth of the Japanese elite, despite losing the war.

In an official report on the occupation prepared by MacArthur’s headquarters and published in 1950, there is a startling admission: “One of the spectacular tasks of the occupation dealt with collecting and putting under guard the great hoards of gold, silver, precious stones, foreign postage stamps, engraving plates, and all currency not legal in Japan.

Even though the bulk of this wealth was collected and placed under United States military custody by Japanese officials, undeclared caches of these treasures were known to exist.”

MacArthur’s staff knew, for example, of $2-billion in gold bullion that had been sunk in Tokyo Bay, later recovered. Another great fortune discovered by U.S. intelligence services in 1946 was $13-billion in war loot amassed by underworld godfather Kodama Yoshio who, as a ‘rear admiral’ in the Imperial Navy working with Golden Lily in China and Southeast Asia, was in charge of plundering the Asian underworld and racketeers. He was also in charge of Japan’s wartime drug trade throughout Asia. Kodama specialized in looting platinum for his own hoard. As this was too heavy to airlift to Japan, Kodama also helped himself to the finest gems looted by his men, taking large bags of gems to Japan each time he flew back during the war.

After the war, to get out of Sugamo Prison and avoid prosecution for war crimes, Kodama gave over $100-million in US currency to the CIA. He was also, amazingly, put on General Willoughby’s payroll, and remained on the CIA payroll for the rest of his life, among other favors brokering the Lockheed aircraft deal that became a major scandal for Japan’s Liberal Demopcratic Party. Kodama personally financed the creation of the postwar political parties that merged into the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), strongly backed to this day by Washington.

Both Kodama and his underworld associate Sasakawa Ryiochi, were then involved with the CIA in joint recoveries of Japanese war-loot from the Philippines.

On September 2, 1945, after receiving official notice of Japan’s surrender, General Yamashita and his staff emerged from their mountain stronghold in the Kiangan Pocket on Luzon, and presented their swords to a group of U.S. Army officers led by Military Police Major A.S. ‘Jack’ Kenworthy, who took them to Bilibad Prison outside Manila. Because of gruesome atrocities committed earlier by Admiral Iwabuchi Kanji’s sailors and marines in the city of Manila (after Yamashita had ordered them to leave the city unharmed), the general was charged with war crimes. During his trial there was no mention of war loot. But there was a hidden agenda.

Because it was not possible to torture General Yamashita physically without this becoming evident to his defense attorneys, members of his staff were tortured instead. His driver, Major Kojima Kashii, was given special attention. Since Yamashita had arrived from Manchuria in October 1944 to take over the defense of the Philippines, Kojima had driven him everywhere.

In charge of Kojima’s torture was a Filipino-American intelligence officer named Severino Garcia Diaz Santa Romana, a man of many names and personalities, whose friends called him ‘Santy’. He wanted Major Kojima to reveal each place to which he had taken Yamashita, where bullion and other treasure were hidden.

Supervising Santy was Captain Edward G. Lansdale, later one of America’s best-known Cold Warriors. In September 1945, Lansdale was 37 years old and utterly insignificant, only an advertising agency copywriter who had spent the war in San Francisco writing propaganda for the 0SS. In September 1945, chance entered Lansdale’s life in a big way when President Truman ordered the OSS to close down. To preserve America’s intelligence assets, and his own personal network, OSS chief Donovan moved personnel to other government or military posts. Captain Lansdale was one of fifty office staff given a chance to transfer to U.S. Army G-2 in the Philippines.

There, Lansdale heard about Santy torturing General Yamashita’s driver, and joined the torture sessions as an observer and participant.

Early that October, Major Kojima broke down and led Lansdale and Santy to more than a dozen Golden Lily treasure vaults in the mountains north of Manila.

While Santy and his teams set to opening the rest of these vaults, Captain Lansdale flew to Tokyo to brief General MacArthur, then on to Washington to brief President Truman. After discussions with his cabinet, Truman decided to proceed with the recovery, but to keep it a state secret.

The treasure – gold, platinum, and barrels of loose gems – was combined with Axis loot recovered in Europe to create a worldwide covert political action fund to fight communism. This ‘black gold’ gave the Truman Administration access to virtually limitless unvouchered funds for covert operations. It also provided an asset base that was used by Washington to reinforce the treasuries of its allies, to bribe political leaders, and to manipulate elections in foreign countries...

After briefing President Truman and others in Washington, including McCloy, Lovett, and Stimson, Captain Lansdale returned to Tokyo in November 1945 with Robert B. Anderson. General MacArthur then accompanied Anderson and Lansdale on a covert flight to Manila, where they set out for a tour of the vaults Santy already had opened. In them, we were told, Anderson and MacArthur strolled down “row after row of gold bars stacked two meters tall”. From what they saw, it was evident that over a period of 50 years (1895-1945) Japan had looted many billions of dollars in treasure from all over Asia. A far longer period than Germany had to loot Europe. Over five decades, Japan had looted billions of dollars’ worth of gold, platinum, diamonds, and other treasure, from all over East and Southeast Asia. Much of this had reached Japan by sea, or overland from China through Korea. What was seen by Anderson and MacArthur was only some of the gold that had not reached Japan after 1943, when the US submarine blockade of the Home Islands became effective. From this it is obvious that what was looted by Japan on the Asian mainland from 1895-1943 had reached Japan and been tucked away there in what the US Army statement called “undeclared caches of these treasures ... known to exist” .

Far from being bankrupted by the war, Japan had been greatly enriched, and -- thanks to Washington’s intervention -- used this treasure to rise like a phoenix from the ashes, while its victims struggled on for decades.

The gold recovered in the Philippines was not put in Fort Knox to benefit American citizens. There has been no audit of Ft. Knox since 1950.

According to Ray Cline and others, between 1945 and 1947 the gold bullion recovered by Santy and Lansdale was discreetly moved by ship to 176 accounts at banks in 42 countries. The gold was trucked to warehouses at the U.S. Navy base in Subic Bay, or the U.S. Air Force base at Clark Field.

Preference went to the U.S. Navy because of the weight of the bullion. Secrecy was vital. If the recovery of a huge mass of stolen gold became known, the market price of gold would plummet, and thousands of people would come forward to claim it, and Washington would be bogged down resolving ownership.

The secrecy surrounding these recoveries was total. Robert Anderson and CIA agent Paul Helliwell traveled all over the planet, setting up these black gold accounts, providing money for political action funds throughout the noncommunist world. In 1953, to reward him, President Eisenhower nominated Anderson to a Cabinet post as secretary of the Navy. The following year he rose to deputy secretary of Defense. During the second Eisenhower Administration, he became secretary of the Treasury, serving from 1957 to 1961. After that, Anderson resumed private life, but remained intimately involved with the CIA’s worldwide network of “black banks”, set up by Paul Helliwell. Eventually, this led to Anderson being involved in the scandal of BCCI, the Bank of Credit and Commerce International, a Pakistani bank with CIA ties.

No one made better use of the recoveries than Lansdale. For his role in enabling the Black Eagle Trust, Lansdale became the darling of the Dulles brothers and their Georgetown coven, which included key officials in the CIA during the years it was run by Allen Dulles. Writing to the U.S. Ambassador in Manila, Admiral Raymond Spruance, Allen Dulles called Lansdale “our mutual friend”. In the early 1950s, Allen Dulles gave Lansdale $5-million to finance CIA operations against the Huks, rural peasant farmers fighting for land-reform in the Philippines. When he sent Lansdale to Vietnam in 1954, Dulles told Eisenhower he was sending one of his “best men”. In the late 1950s, he was in and out of Tokyo on secret missions with a hand-picked team of Filipino assassins, assassinating leftists, liberals and progressives.

Lansdale was also close to Richard Nixon, and headed efforts to assassinate Cuba’s Fidel Castro. Without exception, Lansdale’s Asian adventures were costly failures. But Washington’s effort to boost the LDP in Japan was a big success.

(14) Matthew Alford and Robbie Graham, The Guardian (14th November, 2008)

Everyone who watches films knows about Hollywood's fascination with spies. From Hitchcock's postwar espionage thrillers, through cold war tales such as Torn Curtain, into the paranoid 1970s when the CIA came to be seen as an agency out of control in films such as Three Days of the Condor, and right to the present, with the Bourne trilogy and Ridley Scott's forthcoming Body of Lies, film-makers have always wanted to get in bed with spies. What's less widely known is how much the spies have wanted to get in bed with the film-makers. In fact, the story of the CIA's involvement in Hollywood is a tale of deception and subversion that would seem improbable if it were put on screen.

The model for this is the defence department's "open" but barely publicised relationship with Hollywood. The Pentagon, for decades, has offered film-makers advice, manpower and even hardware - including aircraft carriers and state-of-the-art helicopters. All it asks for in exchange is that the US armed forces are made to look good. So in a previous Scott film, Black Hawk Down, a character based on a real-life soldier who had also been a child rapist lost that part of his backstory when he came to the screen.

No matter how seemingly craven Hollywood's behaviour towards the US armed forces has seemed, it has at least happened within the public domain. That cannot be said for the CIA's dealings with the movie business. Not until 1996 did the CIA announce, with little fanfare, that it had established an Entertainment Liaison Office, which would collaborate in a strictly advisory capacity with film-makers. Heading up the office was Chase Brandon, who had served for 25 years in the agency's elite clandestine services division, as an undercover operations officer. A PR man he isn't, though he does have Hollywood connections: he's a cousin of Tommy Lee Jones.

But the past 12 years of semi-acknowledged collaboration were preceded by decades in which the CIA maintained a deep-rooted but invisible influence of Hollywood. How could it be otherwise? As the former CIA man Bob Baer - whose books on his time with the agency were the basis for Syriana - told us: "All these people that run studios - they go to Washington, they hang around with senators, they hang around with CIA directors, and everybody's on board."

There is documentary evidence for his claims. Luigi Luraschi was the head of foreign and domestic censorship for Paramount in the early 1950s. And, it was recently discovered, he was also working for the CIA, sending in reports about how film censorship was being employed to boost the image of the US in movies that would be seen abroad. Luraschi's reports also revealed that he had persuaded several film-makers to plant "negroes" who were "well-dressed" in their movies, to counter Soviet propaganda about poor race relations in the States. The Soviet version was rather nearer the truth.

Luraschi's activities were merely the tip of the iceberg. Graham Greene, for example, disowned the 1958 adapatation of his Vietnam-set novel The Quiet American, describing it as a "propaganda film for America". In the title role, Audie Murphy played not Greene's dangerously ambiguous figure - whose belief in the justice of American foreign policy allows him to ignore the appalling consequences of his actions - but a simple hero. The cynical British journalist, played by Michael Redgrave, is instead the man whose moral compass has gone awry. Greene's American had been based in part on the legendary CIA operative in Vietnam, Colonel Edward Lansdale. How apt, then, that it should have been Lansdale who persuaded director Joseph Mankewiecz to change the script to suit his own ends.

The CIA didn't just offer guidance to film-makers, however. It even offered money. In 1950, the agency bought the rights to George Orwell's Animal Farm, and then funded the 1954 British animated version of the film. Its involvement had long been rumoured, but only in the past decade have those rumours been substantiated, and the tale of the CIA's role told in Daniel Leab's book Orwell Subverted.

The most common way for the CIA to exert influence in Hollywood nowadays is not through anything as direct as funding, or rewriting scripts, but offering to help with matters of verisimilitude. That is done by having serving or former CIA agents acting as advisers on the film, though some might wonder whether there is ever really such a thing a "former agent". As ex-CIA agent Lindsay Moran, the author of Blowing My Cover, has noted, the CIA often calls on former officers to perform tasks for their old employer.

So it was no problem for CBS to secure official help when making its 2001 TV series The Agency (it was even written by a former agent). Langley was equally helpful to the novelist Tom Clancy, who was invited to CIA headquarters after the publication of The Hunt for Red October, an invitation that was regularly repeated. Consequently, when Clancy's The Sum of All Fears was filmed in 2002, the agency was happy to bring its makers to Langley for a personal tour of headquarters, and to offer access to agency analysts for star Ben Affleck. When filming began, Brandon was on set to advise - a role he repeated during the filming of glamorous television series Alias.

(15) Hugh Wilford, The Mighty Wurlitzer: How the CIA Played America (2008)

Perhaps the most remarkable instance of cooperation between Lansdale and the American Friends of Vietnam involved a third party: movie director, producer, and screenwriter Joseph L. Mankiewicz. Early in 1956 Mankiewicz, whose filmography included such popular and critical successes as The Philadelphia Story and All About Eve, visited Saigon to research locations for a cinematic version of Greene's The Quiet American. During this trip, he met both with staff of the International Rescue Committee's Vietnam office and Lansdale himself, who followed up the encounter with a long letter offering various pieces of advice about the project, chief of which was the suggestion that Mankiewicz depict an incident portrayed in Greene's novel, the bombing of a Saigon square in 1952 by a Vietnamese associate of Lansdale's, General Trinh Minh The (and attributed by Greene to the baleful influence of the American, Pyle), as "actually having been a Communist action."

On his return home, Mankiewicz contacted the chair of the AFV, Iron Mike O'Daniel, telling him that he intended "completely chang[ing] the anti-American attitude" of Greene's book. The U.S. ambassador to South Vietnam, Frederick Reinhardt, was sympathetic but skeptical, telling the American Friends of Vietnam's Executive Committee: "If (the book) were to be edited into a state of complete unobjectionahleness, there might be nothing left but the title and scenery." This is, however, precisely what Mankiewicz proceeded to do, turning the American character into his hero and portraying Greene's fictional alter ego and Pyle's nemesis, the English journalist Fowler, as a communist stooge. Not only that, in an astonishing piece of casting apparently suggested by O'Daniel, the part of Pyle - in Greene's novel, a callow Ivy League hrahmin - was given to the World War ll hero Audie Murphy, a fine soldier but limited actor, who reportedly distressed his English costar, Michael Redgrave, by storing a .45 and 500 rounds of ammunition in his Saigon hotel room to protect himself from Vietminh agents. "I figured if they were going to get me," he explained, "I'd give them a good fight first."

The resulting movie was a travesty of Greene's book, but Lansdale was delighted. After a premiere at Washington's Playhouse Theater, the proceeds of which were donated to the AFV, the spy wrote his friend Diem describing "Mr. Mankiewicz's 'treatment' of the story" as "an excellent change from Mr. Greene's novel of despair," and suggesting "that it will help win more friends for you and Vietnam in any places in the world where it is shown."