Simplicissimus

Albert Langen, the son of a Rhineland industrialist, started Simplicissimus in 1896. His first recruit was the cartoonist, Thomas Heine. Each week Heine provided the drawing that appeared on the front cover of Simplicissimus. He also persuaded several talented writers such as Thomas Mann, Frank Wedekind and Rainer Maria Rilke to contribute to the magazine.

Simplicissimus looked very different to other satirical journals published in Germany. It relied heavily on its visual impact and included more cartoons than its rivals. It also experimented with modern graphics and bright colours. The imagery used by the artists at Simplicissimus was based on everyday life whereas older journals such as Kladderadatsch made references to traditional sources such as classical mythology.

Although a supporter of liberal causes, Simplicissimus appeared revolutionary when compared to established journals such as Kladderadatsch. It especially upset the German government by objecting to a law in 1897 that penalized striking workers. It also supported trade unionists in their struggle with employers during this period.

Wilhelm II disliked liberal journals like Simplicissimus and warned that it was undermining Germany's international prestige: "Every country is, in the long run, responsible for the window which its press opens up on the world. It will someday bear the consequences of its indiscretions - the hostility of foreign lands."

In 1898 Wilhelm II objected to an article and cartoon that appeared in Simplicissimus during his visit to Palestine. The issue was confiscated and a lawsuit was brought against the publisher (Albert Langen), the writer (Frank Wedekind) and the cartoonist (Thomas Heine). Following the advice of his lawyer, Langen fled to Switzerland and remained in exile for five years. Both Heine (six months) and Wedekind (seven months) were imprisoned for their attack on the German monarchy.

Olaf Gulbransson, a cartoonist from Norway, joined the magazine in 1902 and had a considerable influence on the journal. Other important cartoonists who worked for Simplicissimus during this period included Rudolf Wilke, Walter Trier and Edward Thony. Simplicissimus constantly attacked the German establishment. One right-wing journal in Germany, Augsburger Postzeitung, complained about the influence that Simplicissimus was having on young students and called for it to be banned as is was creating a "real danger to school discipline".

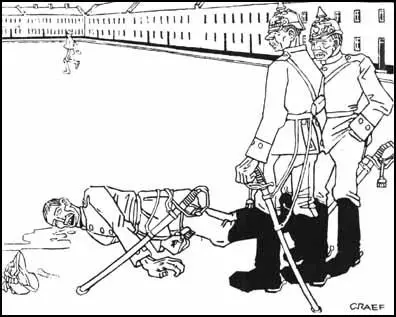

have gotten two years in the stockade.

Simplicissimus (September, 1910)

In 1905 the journal campaigned against the proposed voting reforms. Like other liberals, the owners of Simplicissimus objected to a system where votes were unequally weighted and virtually assured the continuing power of the land-owning aristocracy. Simplicissimus also attacked German militarism and the privileges enjoyed by leaders of the German Army. It was particularly critical of the military rules and regulations that enabled the army to impose heavy punishments on its soldiers.

In 1906 the editor of Simplicissimus, Ludwig Thoma was imprisoned for six months for an article he wrote criticizing Catholic and Protestant clergy. However, it soon became clear that these well-publicized court cases actually helped the journal. As a result of the court case, circulation increased from 15,000 to 85,000. When the king of Bavaria objected to one particular edition and demanded that action be taken against Simplicissimus, his police chief warned against the move pointing out that "prohibition would be ineffective and would only serve as an advertisement".

In 1906 several staff members, including Ludwig Thoma, Thomas Heine, Olaf Gulbransson, Rudolf Wilke, and Edward Thony persuaded Albert Langen to change Simplicissimus into a joint stock company. This gave more power to the staff to control the direction of the journal. Thoma, a former lawyer, became editor-in-chief of Simplicissimus after the death of Langen in 1909.

Leaders of the Social Democratic Party (SDP) and the Communist Party (KPD) began to criticise Simplicissimus for its illustrations. On the 28th December, 1908, Kölnische Zeitung reported: " The German worker simply does not look the way Simplicissimus portrays him. The worker, who strives courageously for the recognition of his personal worth, is insulted when he is portrayed as a drunkard or as a ragged street urchin living in an evil-smelling hovel.

In 1909 Simplicissimus responded to this by commissioning Käthe Kollwitz to produce a series of five drawings entitled Portraits of Misery. Käthe was married to Karl Kollwitz, a doctor in a working-class district of Berlin and based her charcoal drawings on the working-class people who visited her husband's surgery for treatment. "I met the women who came to my husband for help and so, incidentally, came to me, I was gripped by the full force of the proletarian's fate. Unsolved problems such as prostitution and unemployment grieved and tormented me, and contributed to my feeling that I must keep on with my studies of the lower classes. And portraying them again and again opened a safety-valve for me; it made life bearable."

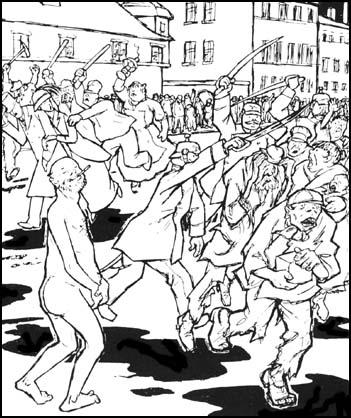

the police beat you up. Oh well - in this outfit nothing can happen to me!

Thomas Heine, Simplicissimus (October, 1910)

In 1910 socialists and trade unionists in Germany organised massive demonstrations in favour of liberal reforms. This demonstrations frequently escalated into violent classes with the police. Several of the cartoons published in Simplicissimus during this period complained of police brutality. However, Simplicissimus remained critical of the behaviour of left-wing demonstrators and in one cartoon by Thomas Heine, they were accused of using violence against the middle classes.

Simplicissimus was opposed to the foreign policy of the German government before the outbreak of the First World War. However, once fighting began, Simplicissimus gave its full support to the war effort. Ludwig Thoma, the editor, later reported: "All of us had supported peace. With no cautious reservations we had denounced the personal rule and all its harmful manifestations. But once the war was there nothing mattered but our own country."

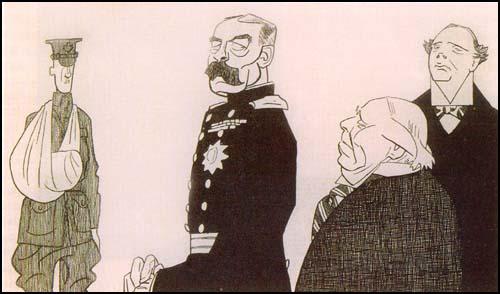

bad as they look. Cartoon from the German magazine, Simplicissimus (May, 1915)

Ludwig Thoma called a meeting where he suggested that the journal should close down as : "there was no place for a satirical sheet which opposed the ruling powers of Germany." Thomas Heine disagreed and argued that it was important that Simplicissimus should continue as the "Fatherland needed a periodical of such international prestige to support the war effort." The majority of the staff agreed and it was published throughout the war.

Ludwig Thoma joined the German Army and during the war and in 1917

wrote to a friend and denounced his earlier work with Simplicissimus:

"I used to shout my mouth off. This now seems immature and deplorable.

Belief and criticism are incompatible."

After the Armistice Simplicissimus led the campaign against the Versailles Treaty. Ludwig Thoma, its editor, had served in a medical unit during the war. He no longer held liberal views and instead joined a right-wing group called Deutsche Vaterlandspartei.

Thoma ceased to play an active role in Simplicissimus in the 1920s. Original members of the group that was still with Simplicissimus included Thomas Heine, Olaf Gulbransson, and Edward Thony. The cartoonist, Karl Arnold, was also now one of the owners. Other talented artists such as Erich Schilling, George Grosz and Kathe Kollwitz also contributed to the journal. Simplicissimus was unable to increase its circulation and during the 1920s hovered around 30,000 copies, compared to the 86,000 it achieved in 1914.

In the 1920s Simplicissimus defended the Weimar Republic against threats from the revolutionary left and right-wing nationalism. It strongly opposed Adolf Hitler and the right-wing press accused Simplicissimus of being under the control of the Jews. The Nazis were especially hostile to the cartoons of Thomas Heine and Walter Trier. When the Nazis gained power in 1933 stormtroopers arrived at the offices of Simplicissimus and warned against the publication of anti-Hitler cartoons.

When left-wing writers artists began to be arrested in Germany Thomas Heine and Walter Trier left the country but Olaf Gulbransson, Karl Arnold, Erich Schilling and Edward Thony carried on working at Simplicissimus. Although most refused to actively support the regime Schilling became a fervent support of the new regime. Simplicissimus continued during the early stages of the Second World War but finally ceased publication in 1944

Primary Sources

(1) Kölnische Zeitung (28th December, 1908)

The German worker simply does not look the way Simplicissimus portrays him. The worker, who strives courageously for the recognition of his personal worth, is insulted when he is portrayed as a drunkard or as a ragged street urchin living in an evil-smelling hovel.

(2) Ludwig Thoma, letter to Conrad Haussmann (1917)

I used to shout my mouth off. This now seems immature and deplorable. Belief and criticism are incompatible.

(3) Ludwig Thoma, Autobiography (1933)

All of us had supported peace. With no cautious reservations we had denounced the personal rule and all its harmful manifestations. But once the war was there nothing mattered but our own country.