George Ward Nichols

George Ward Nichols was born in Tremont, Maine, on 21st June, 1831. He worked as a journalist until the outbreak of the American Civil War. Nichols joined the Union Army and served on the staff of General John C. Fremont. Later he served under General William Sherman and rose to the rank of lieutenant colonel. He published The Story of the Great March in 1865.

After the war Nichols became a journalist. He visited Kansas and in 1866 interviewed Wild Bill Hickok about his exploits as a gunfighter. The article appeared in the February, 1867, edition of Harper's New Monthly Magazine. Newspapers such as the Leavenworth Daily Conservative, Kansas Daily Commonwealth, Springfield Patriot and the Atchison Daily Champion quickly pointed out that the article was full of inaccuracies and that Hickok was lying when he claimed he had killed "hundreds of men".

After the heavy attacks he received for his article in the Harper's New Monthly Magazine Nichols moved to Cincinnati, Ohio, and concentrated on writing about music. He also became president of the Cincinnati College of Music. Books by Nichols include Art Education Applied to Industry (1877) and Pottery (1878).

George Ward Nichols died on 15th September, 1885.

Harper's New Monthly Magazine (February, 1867)

Primary Sources

(1) Colonel George Ward Nichols, Harper's New Monthly Magazine (February, 1867)

Let me at once describe the personal appearance of the famous Scout of the Plains, William Hitchcock, called "Wild Bill," who now advanced toward me, fixing his clear gray eyes on mine in a quick, interrogative way, as if to take "my measure."

The result seemed favorable, for he held forth a small, muscular hand in a frank, open manner. As I looked at him I thought his the handsomest physique I had ever seen.

Bill stood six feet and an inch in his bright yellow moccasins. A deer-skin shirt, or frock it might be called, hung jauntily over his shoulders and revealed a chest whose breadth and depth were remarkable. These lungs had had growth in some twenty years of the free air of the Rocky Mountains. His small, round waist was girthed by a belt which held two of Colt's navy revolvers. His legs sloped gradually from the compact thigh to the feet, which were small and turned inward as he walked. There was a singular grace and dignity of carriage about that figure which would have called your attention meet it where you would. The head which crowned it was now covered by a large sombrero, underneath which there shone out a quiet, manly face; so gentle is its expression as he greets you as utterly to belie the history of its owner; yet it is not a face to be trifled with. The lips thin and sensitive, the jaw not too square, the cheek bones slightly prominent, a mass of fine dark hair falls below the neck to the shoulders. The eyes, now that you are in friendly intercourse, are as gentle as a woman's. In truth, the woman nature seems prominent throughout, and you would not believe that you were looking into eyes that have pointed the way to death to hundreds of men. Yes, Wild Bill with his own hands has killed hundreds of men. Of that I have not a doubt. "He shoots to kill," they say on the border.

In vain did I examine the scout's face for some evidence of murderous propensity. It was a gentle face, and singular only in the sharp angle of the eye, and without any physiognomic reason for the opinion, I have thought his wonderful accuracy of aim was indicated by this peculiarity. He told me, however, to use his own words:

"I allers shot well; but I come ter be perfect in the mountains by shootin at a dime for a mark, at best of half a dollar a shot. And then until the war I never drank liquor nor smoked," he continued, with a melancholy expression; "war is demoralizing it is."

Captain Honesty was right. I was very curious to see "Wild Bill, the Scout," who, a few days before my arrival in Springfield, in a duel at noonday in the public square, at fifty paces, had sent one of Colt's pistol-balls through the heart of a returned Confederate soldier. . . .

"To tell you the truth, Kernel," responded the scout with a certain solemnity in his grave face, "I don't talk about sich things ter the people round here, but I allers feel sort of thankful when I get out of a bad scrape."

"In all your wild, perilous adventures," I asked him, "have you ever been afraid? Do you know what the sensation is? I am sure you will not misunderstand the question, for I take it we soldiers comprehend justly that there is no higher courage than that which shows itself when the consciousness of danger is keen but where moral strength overcomes the weakness of the body."

"I think I know what you mean, Sir, and I'm not ashamed to say that I have been so frightened that it 'peared is if all the strength and blood had gone out of my body, and my face was as white as chalk. It was at the Wilme Creek fight. I had fired more than fifty cartridges, and I think fetched my man every time. I was on the skirmish line, and was working up closer to the rebs, when all of a sudden a battery opened fire right in front of me, and it sounded as if forty thousand guns were firing, and every shot and shell screeched within six inches of my head. It was the first time I was ever under artillery fire, and I was so frightened that I couldn't move for a minute or so, and when I did go back the boys asked me if I had seen a ghost? They may shoot bullets at me by the dozen, and it's rather exciting if I can shoot back, but I am always sort of nervous when the big guns go off."

"I would like to see you shoot."

"Would yer?" replied the scout, drawing his revolver; and approaching the window, he pointed to a letter O in a sign-board which was fixed to the stone-wall of a building on the other side of the way.

"That sign is more than fifty yards away. I will put these six balls into the inside of the circle, which isn't bigger than a man's heart."

In an off-hand way, and without sighting the pistol with his eye, he discharged the six shots of his revolver. I afterwards saw that all the bullets had entered the circle.

As Bill proceeded to reload his pistol, he said to me with a naiveté of manner which was meant to be assuring:

"Whenever you get into a row be sure and not shoot too quick. Take time. I've known many a feller slip up for shootin' in a hurry,"

It would be easy to fill a volume with the adventures of that remarkable man. My object here has been to make a slight record of one who is one of the best - perhaps the very best - example of a class who more than any other encountered perils and privations in defense of our nationality.

One afternoon as General Smith and I mounted our horses to start upon our journey toward the East, Wild Bill came to shake hands good-bye, and I said to him:

"If you have no objection I will write out for publication an account of a few of your adventures."

"Certainly you may," he replied. "I'm sort of public property. But, Kernel," he continued, leaning upon my saddle bow, while there was a tremulous softness in his voice and a strange moisture in his averted eyes, "I have a mother back there in Illinois who is old and feeble. I haven't seen her this many a year, and haven't been a good son to her, yet I love her better than any thing in this life. It don't matter much what they say about me here. But I'm not a cut-throat and vagabond, and I'd like the old woman to know what'll make her proud. I'd like her to hear that her runaway boy has fought through the war for the Union like a true man."

(2) Leavenworth Daily Conservative (30th January, 1867)

The story of "Wild Bill," as told in Harper's for February is not easily credited hereabouts. To those of us who were engaged in the campaign it sounds mythical; and whether Harry York, Buckskin Joe or Ben Nugget is meant in the life sketches of Harper we are not prepared to say. The scout services were so mixed that we are unable to give precedence to any. "Wild Bill's" exploits at Springfield have not as yet been heard of here, and if under that cognomen such brave deeds occurred we have not been given the relation. There are many of the rough riders of the rebellion now in this city whose record would compare very favorably with that of "Wild Bill," and if another account is wanted we might refer to Walt Sinclair.

(3) Springfield Patriot (31st January, 1867)

Springfield is excited. It has been so ever since the mail of the 25th brought Harper's Monthly to its numerous subscribers here. The excitement, curiously enough, manifests itself in very opposite effects upon our citizens. Some are excessively indignant, but the great majority are in convulsions of laughter, which seem interminable as yet. The cause of both abnormal moods, in our usually placid and quiet city, is the first article in Harper for February, which

all agree, if published at all, should have had its place in the "Editor's Drawer," with the other fabricated more or less funnyisms; and not where it is, in the leading "illustrated" place. But, upon reflection, as Harper has given the same

prominence to "Heroic Deeds of Heroic Men," by Rev. J. T. Headley, which, generally, are of about the same character as its article "Wild Bill," we will not question the good taste of its "make up."

We are importuned by the angry ones to review it. "For," say they, "it slanders our city and citizens so outrageously by its caricatures, that it will deter some from immigrating here, who believe its representations of our people."

"Are there any so ignorant?" we asked.

"Plenty of them in New England; and especially about the Hub, just as ready to swallow it all as Gospel truth, as a Johnny Chinaman or Japanese would be to believe that England, France and America are inhabited by cannibals."

"Don't touch it," cries the hilarious party, "don't spoil a richer morceaux than ever was printed in Gulliver's Travels, or Baron Munchausen! If it prevents any consummate fools from coming to Southwest Missouri, that's no loss."

So we compromise between the two demands, and give the article but brief and inadequate criticism. Indeed, we do not imagine that we could do it justice, if we made ever so serious and studied an attempt to do so.

A good many of our people - those especially who frequent the bar rooms and lager-beer saloons, will remember the author of the article, when we mention one "Colonel" G. W. Nichols, who was here for a few days in the summer of 1865, splurging around among our "strange, half-civilized people," seriously endangering the supply of lager and corn whisky, and putting on more airs than a spotted stud-horse in the ring of a county fair. He's the author! And if the illustrious holder of one of the "Brevet" commissions which Fremont issued to his wagon-masters, will come back to Springfield, two-thirds of all the people he meets will invite him "to pis'n hisself with suth'n" for the fun he unwittingly furnished them in his article - the remaining one-third will kick him wherever met, for lying like a dog upon the city and people of Springfield.

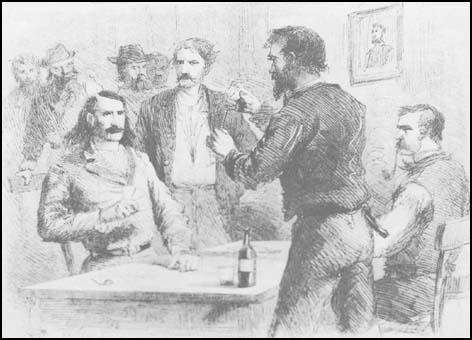

James B Hickok, (not "William Hitchcock," as the "Colonel" mis-names his hero,) is a remarkable man, and is as well known here as Horace Greely in New York, or Henry Wilson in "the Hub." The portrait of him on the first page of Harper for February, is a most faithful and striking likeness - features, shape, posture and dress - in all it is a faithful reproduction of one of Charley Scholten's photographs of "Wild Bill," as he is generally called. No finer physique, no greater strength, no more personal courage, no steadier nerves, no superior skill with the pistol, no better horsemanship than his, could any man of the million Federal soldiers of the war, boast of; and few did better or more loyal service as a soldier throughout the war. But Nichols "cuts it very fat" when he describes Bill's teats in arms. We think his hero only claims to have sent a few dozen rebs to the farther side of Jordan; and we never, before reading the "Colonel's" article, suspected he had dispatched "several hundreds with his own hands." But it must be so, for the "Colonel" asserts it with a parenthesis of genuine flavorous Bostonian piety, to assure us of his incapacity to utter an untruth.

(4) Atchinson Daily Champion (5th February, 1867)

'Wild Bill' is, as stated in the Magazine, a splendid specimen of physical manhood, and is a dead shot with a pistol. He is a very quiet man, rarely talking to any one, and not of a quarrelsome disposition, although reckless and desperate when once involved in a fight. There are a number of citizens of this city who know him well.

Nichols' sketch of 'Wild Bill' is a very readable paper, but the fine descriptive powers of the writer have been drawn upon as largely as facts, in producing it. There are dozens of men on the Overland Line who are probably more desperate characters than Hickok, and are the heroes of quite as many and as desperate adventures. The wild West is fertile in 'Wild Bills.' Charley Slade, formerly one of the division Superintendents on the O. S. Line, was probably a more desperate, as well as a cooler man than the hero of Harper's, and his fight at his own ranch was a much more terrible encounter than that of 'Wild Bill' with the McKandles gang.

(5) Henry M. Stanley, St. Louis Missouri Democrat (4th April, 1867)

James Butler Hickok, commonly called "Wild Bill," is one of the finest examples of that peculiar class known as frontiersman, ranger, hunter, and Indian scout. He is now thirty-eight years old, and since he was thirteen the prairie has been his home. He stands six feet one inch in his moccasins, and is as handsome a specimen of a man as could be found. We were prepared, on hearing of "Wild Bill's" presence in the camp, to see a person who might prove to be a coarse and illiterate bully. We were agreeably disappointed however. He was dressed in fancy shirt and leathern leggings. He held himself straight, and had broad, compact shoulders, was large chested, with small waist, and well-formed muscular limbs. A fine, handsome face, free from blemish, a light moustache, a thin pointed nose, bluish-grey eyes, with a calm look, a magnificent forehead, hair parted from the centre of the forehead, and hanging down behind the ears in wavy, silken curls, made up the most picturesque figure. He is more inclined to be sociable than otherwise; is enthusiastic in his love for his country and Illinois, his native State; and is endowed with extraordinary power and agility, whose match in these respects it would be difficult to find. Having left his home and native State when young, he is a thorough child of the prairie, and inured to fatigue. He has none of the swaggering gait, or the barbaric jargon ascribed to the pioneer by the Beadle penny-liners. On the contrary, his language is as good as many a one that boasts "college laming." He seems naturally fitted to perform daring actions. He regards with the greatest contempt a man that could stoop low enough to perform "a mean action." He is generous, even to extravagance. He formerly belonged to the 8th Missouri Cavalry.

The following dialogue took place between us; "I say, Mr. Hickok, how many white men have you killed to your certain knowledge?" After a little deliberation, he replied, "I suppose I have killed considerably over a hundred." "What made you kill all those men? Did you kill them without cause or provocation?" "No, by heaven I never killed one man without good cause." "How old were you when you killed the first white man, and for what cause?" "I was twenty-eight years old when I killed the first white man, and if ever a man deserved lolling he did. He was a gambler and counterfeiter, and I was then in an hotel in Leavenworth City, and seeing some loose characters around, I ordered a room, and as I had some money about me, I thought I would retire to it. I had lain some thirty minutes on the bed when I heard men at my door. I pulled out my revolver and bowie knife, and held them ready, but half concealed, and pretended to be asleep. The door was opened, and five men entered the room. They whispered together, and one said, "Let us kill the son of a bitch; I'll bet he has got money." "Gentlemen," said he, "that was a time - an awful time. I kept perfectly still until just as the knife touched my breast; I sprang aside and buried mine in his heart, and then used my revolver on the others right and left. One was killed, and another was wounded; and then, gentlemen, I dashed through the room and rushed to the fort, where I procured a lot of soldiers, and returning to the hotel, captured the whole gang of them, fifteen in all. We searched the cellar, and found eleven bodies buried in it - the remains of those who had been murdered by those villains." Turning to us, he asked: "Would you not have done the same? That was the first man I killed, and I never was sorry for that yet."

(6) Henry M. Stanley, St. Louis Missouri Democrat (11th May, 1867)

"Wild Bill," who is an inveterate hater of the Indians, was chased by six Indians lately, and had quite a little adventure with them. It is his custom to be always armed with a brace of ivory-handled revolvers, with which weapons he is remarkably dexterous; but when bound on a long and lonely ride across the plains, he goes armed to the teeth. He was on one of these lonely missions, due to his profession as scout, when he was seen by a group of the red men, who immediately gave chase. They soon discovered that they were pursuing one of the most famous men of the prairie, and commenced to retrace their steps, but two of them were shot, after which Wild Bill was left to ride on his way. The little adventure is verified by a scout named Thomas Kincaid.

(7) Kansas Daily Commonwealth (11th May, 1873)

It is disgusting to see the eastern papers crowding in everything they can get hold of about "Wild Bill." If they only knew the real character of the men they so want to worship, we doubt if their names would ever appear again. "Wild Bill," or Bill Hickok, is nothing more than a drunken, reckless, murderous coward, who is treated with contempt by true border men, and who should have been hung years ago for the murder of innocent men. The shooting of the "old teamster" in the back for a small provocation, while crossing the plains in 1859, is one fact that Harpers correspondent failed to mention, and being booted out of a Leavenworth saloon by a boy bar tender is another; and we might name many other similar examples of his bravery. In one or two instances he did the U. S. government good service, but his shameful and cowardly conduct more than overbalances the good.