Al Capone

Alphonse Capone was born in Brooklyn, New York, in 1899. When he was 22 he was recruited by Johnny Torrio, a bootlegger in Chicago. Torrio was one of the many people who had established his business after the passing of the National Prohibition Act in 1920. Capone's job was to persuade speakeasy proprietors to buy Torrio's illegal alcohol.

Within three years Al Capone had taken over Johnny Torrio's business and controlled 161 illegal drinking establishments. In an attempt to expand his business, Capone developed the policy of killing his competitors.

After the killing of Dion O'Banion in 1926 gang-warfare broke out in Chicago. In one year there were 130 gangsters murdered in just one district of the city. This included the famous St Valentine's Day Massacre when six leading members of the Bugs Moran gang were executed in a garage by gangsters dressed in police uniforms.

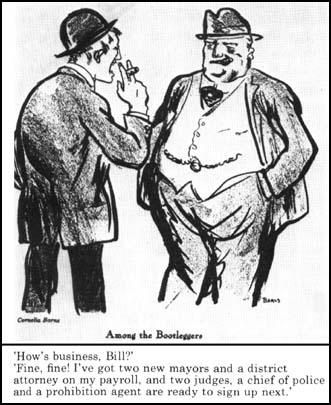

Few of the murderers were arrested and convicted of their crimes. Gangsters like Al Capone were able to use their money to bribe police investigators or intimidate potential witnesses. The police were also hampered by the refusal of any gangster to testify against another gangster.

It is estimated that by 1929, Al Capone's income from the various aspects of his business was $60,000,000 (illegal alcohol), $25,000,000 (gambling establishments), $10,000,000 (vice) and $10,000,000 from various other rackets. It is claimed that Capone was employing over 600 gangsters to protect this business from rival gangs.

(If you find this article useful, please feel free to share. You can follow John Simkin on Twitter, Google+ & Facebook or subscribe to our monthly newsletter)

The journalist Claude Cockburn interviewed Capone in 1930. When Cockburn suggested that Capone had become a gangster because of poverty he replied: "Listen, don't get the idea I'm one of these goddam radicals. Don't get the idea I'm knocking the American system.... My rackets are run on strictly American lines and they're going to stay that way... This American system of ours, call it Americanism, call it Capitalism, call it what you like, gives to each and every one of us a great opportunity if we only seize it with both hands and make the most of it."

Al Capone openly admitted how he had obtained his wealth. "I make my money by supplying a public demand. If I break the law, my customers who number hundreds of the best people in Chicago, are as guilty as I am. The only difference is that I sell and they buy. Everybody calls me a racketeer. I call myself a businessman."

Unable to obtain the evidence to convict Capone of murder, in 1931 the authorities decided to charge him with tax evasion. Found guilty Capone was sentenced to eleven years imprisonment. When Capone was released in 1939 prohibition had come to an end and he was he was no longer able to make money from selling illegal alcohol. He was also showing signs of the effects of syphilis and no longer had the mental strength to obtain past loyalties.

Alphonse Capone died in 1947.

Primary Sources

(1) Claude Cockburn, interviewed Al Capone in 1930. He later wrote about it in his book, In Time of Trouble (1956)

The Prohibition-era gangster Alphonse Capone was born in Brooklyn, but achieved his notoriety as a Mafia boss in Chicago. The Lexington Hotel had once, I think, been a rather grand family hotel, but now its large and gloomy lobby was deserted except for a couple of bulging Sicilians and a reception clerk who looked at one across the counter with the expression of a speakeasy proprietor looking through the grille at a potential detective. He checked on my appointment with some superior upstairs, and as I stepped into the elevator I felt my hips and sides being gently frisked by the tapping hands of one of the lounging Sicilians. There were a couple of ante-rooms to be passed before you got to Capone's office and in the first of them I had to wait for a quarter of an hour or so, drinking whisky poured by a man who used his left hand for the bottle and kept the other in his pocket.

Except that there was a sub-machine-gun, operated by a man called MacGurn - whom I later got to know and somewhat esteem - poking through the transom of a door behind the big desk, Capone's own room was nearly indistinguishable from that of, say, a 'newly arrived' Texan oil millionaire. Apart from the jowly young murderer on the far side of the desk, what took the eye were a number of large, flattish, solid silver bowls upon the desk, each filled with roses. They were nice to look at, and they had another purpose too, for Capone when agitated stood up and dipped the tips of his fingers in the waters in which floated the roses.

I had been a little embarrassed as to how the interview was to be launched. Naturally the nub of all such interviews is somehow to get around to the question "What makes you tick?" but in the case of this millionaire killer the approach to this central question seemed mined with dangerous impediments. However, on the way down to the Lexington Hotel I had had the good fortune to see, in I think the Chicago Daily News, some statistics offered by an insurance company which dealt with the average expectation of life of gangsters in Chicago. I forget exactly what the average expectation was, and also what the exact age of Capone at that time was - I think he was in his early thirties. The point was, however, that in any case he was four years older than the upper limit considered by the insurance company to be the proper average expectation of life for a Chicago gangster. This seemed to a offer a more or less neutral and academic line of approach, and after the ordinary greetings I asked Capone whether he had read this piece of statistics in the paper. He said that he had. I asked him whether he considered the estimate reasonably accurate. He said that he thought that the insurance companies and the newspaper boys probably knew their stuff. "In that case," I asked him, "how does it feel to be, say, four years over the age?"

He took the question quite seriously and spoke of the matter with neither more nor less excitement or agitation than a man would who, let us say, had been asked whether he, as the rear machine-gunner of a bomber, was aware of the average incidence of casualties in that occupation. He apparently assumed that sooner or later he would be shot despite the elaborate precautions which he regularly took. The idea that - as afterwards turned out to be the case - he would be arrested by the Federal authorities for income-tax evasion had not, I think, at that time so much as crossed his mind. And, after all, he said with a little bit of corn-and-ham somewhere at the back of his throat, supposing he had not gone into this racket? What would he have been doing? He would, he said, "have been selling newspapers barefoot on the street in Brooklyn".

He stood up as he spoke, cooling his finger-tips in the rose bowl in front of him. He sat down again, brooding and sighing. Despite the ham-and-corn, what he said was quite probably true and I said so, sympathetically. A little bit too sympathetically, as immediately emerged, for as I spoke I saw him looking at me suspiciously, not to say censoriously. My remarks about the harsh way the world treats barefoot boys in Brooklyn were interrupted by an urgent angry waggle of his podgy hand.

"Listen," he said, "don't get the idea I'm one of these goddam radicals. Don't get the idea I'm knocking the American system. The American system... " As though an invisible chairman had called upon him for a few words, he broke into an oration upon the theme. He praised freedom, enterprise and the pioneers. He spoke of "our heritage". He referred with contemptuous disgust to Socialism and Anarchism. "My rackets," he repeated several times, "are run on strictly American lines and they're going to stay that way."

His vision of the American system began to excite him profoundly and now he was on his feet again, leaning across the desk like the chairman of a board meeting, his fingers plunged in the rose bowls.

"This American system of ours," he shouted, "call it Americanism, call it Capitalism, call it what you like, gives to each and every one of us a great opportunity if we only seize it with both hands and make the most of it." He held out his hand towards me, the fingers dripping a little, and stared at me sternly for a few seconds before reseating himself.