Appeasement: 1935-1938

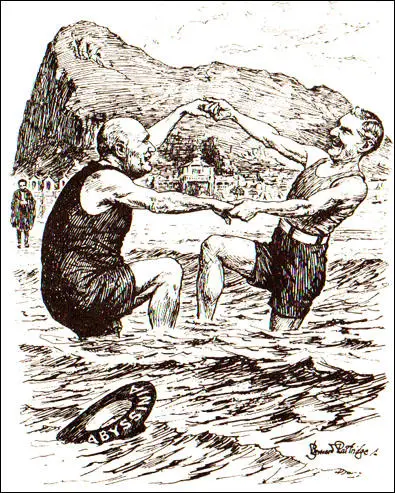

On 3rd October 1935, Benito Mussolini sent 400,000 soldiers to invade Abyssinia (Ethiopia). Haile Selassie, the ruler of the country, appealed to the League of Nations for help, delivering an address that made him a worldwide figure. As might have been expected, given his views of black people, Winston Churchill had little sympathy for one of the two last surviving independent African countries. Churchill told the House of Commons: "No one can keep up the pretence that Abyssinia is a fit, worthy and equal member of a league of civilised nations." (1)

As the majority of the Ethiopian population lived in rural towns, Italy faced continued resistance. Haile Selassie fled into exile and went to live in England. Mussolini was able to proclaim the Empire of Ethiopia and was given full support by the Italian king Victor Emmanuel III. The League of Nations condemned Italy's aggression and imposed economic sanctions in November 1935, but these measures were largely ineffective since they did not ban the sale of oil or close the Suez Canal, that was under the control of the British. Despite the illegal methods employed by Mussolini, Churchill remained a loyal supporter. He told the Anti-Socialist Union that Mussolini was "the greatest lawgiver among living men". (2) He also wrote in The Sunday Chronicle that Mussolini was "a really great man". (3)

Labour Party and Rearmament

In November, 1935, Clement Attlee was elected to replace George Lansbury as leader of the Labour Party. Over the next few months he attempted to persuade the Party to change its view on rearmament. As Trevor Burridge, the author of British Labour & Hitler's War (1976) has pointed out: "Though the Party never officially adopted an outright pacifist position, a dedicated pacifist, George Lansbury, was Leader of the Party from 1932-35. In addition, Socialist theory interpreted war in economic terms as a clash of rival imperialism - the last, most decadent stage of capitalism." (4)

The left of the Labour Party argued that its policy should be to oppose rearmament and stimulate international socialist co-operation to avoid a capitalist war. From the right came the proposition that the party must support rearmament to defend freedom and democracy. (5) In one speech Attlee argued: "We are against the use of force for imperialist and capitalist ends, but we are in favour of the proper use of force for ensuring the use of law. I do not believe that non-resistance is a possible policy for people with responsibility." (6)

At the 1935 Labour Party Conference, Sydney Silverman, the MP for Nelson and Colne, argued that there should be no cooperation with the government on rearmament, and the Party should be involved in "a movement of resistance" in the country and to "re-establish international working-class unity in active resistance to capitalist and imperial war". (7) Ernest Bevin took the opposite view: "I would vote for armaments to defend democracy and our liberty, I would also say, strive with all our might to build the great moral authority behind international law." (8)

Clement Attlee, agreed with Bevin, and the executive's resolution was passed by 1,438 million votes to 657,000. However, Attlee admitted that it would take some time before he could get complete control of his Party. He told his brother, Tom Attlee: "I am not prepared to arrogate to myself a superiority to the rest of the movement. I am prepared to submit to their will, even if I disagree. I shall do all I can to get my views accepted, but, unless acquiescence in the views of the majority conflicts with my conscience, I shall fall into line, for I have faith in the wisdom of the rank and file." (9)

Hitler's Rhineland Coup

Adolf Hitler knew that both France and Britain were militarily stronger than Germany. However, their failure to take action against Italy, convinced him that they were unwilling to go to war with Germany. He therefore decided to break another aspect of the Treaty of Versailles by sending German troops into the Rhineland. The German generals were very much against the plan, claiming that the French Army would win a victory in the military conflict that was bound to follow this action. Hitler ignored their advice and on 1st March, 1936, three German battalions marched into the Rhineland. Hitler later admitted: "The forty-eight hours after the march into the Rhineland were the most nerve-racking in my life. If French had then marched into the Rhineland we would have had to withdraw with our tails between our legs, for the military resources at our disposal would have been wholly inadequate for even a moderate resistance." (10)

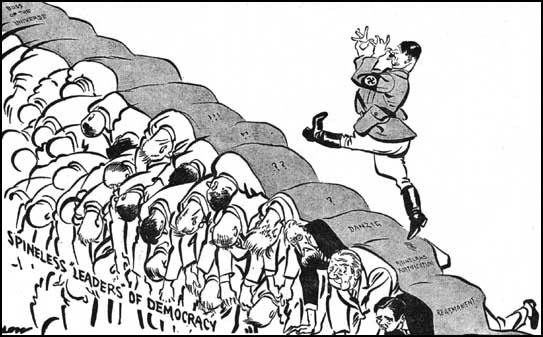

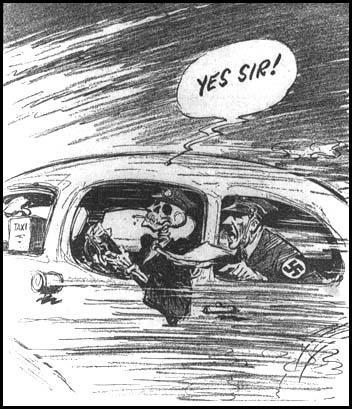

say, twenty-five years?", Evening Standard (12th March, 1936)

The British government accepted Hitler's Rhineland coup. Sir Anthony Eden, the new foreign secretary, informed the French that the British government was not prepared to support military action. The chiefs of staff felt Britain was in no position to go to war with Germany over the issue. The Rhineland invasion was not seen by the British government as an act of unprovoked aggression but as the righting of an injustice left behind by the Treaty of Versailles. Eden apparently said that he would not oppose the move because "Hitler was only going into his own back garden." (11)

Winston Churchill agreed with the government position. In an article in the Evening Standard he praised the French for their restraint: "instead of retaliating with arms, as the previous generation would have, France has taken the correct course by appealing to the League of Nations". (12) In a speech in the House of Commons he supported the government's policy on appeasement and called on the League of Nations to invite Germany to state her grievances and her legitimate aspirations" so that under the League's auspices "justice may be done and peace preserved". (13)

Clement Attlee attacked Churchill, Baldwin and Eden and the Conservative government for the acceptance that Hitler was allowed to march into the Rhineland without any measures taken against Germany. He spoke of the dangers of accepting Hitler's actions as merely righting one of the punitive wrongs of Versailles. "In the last five years we have had quite enough of dodging difficulties, of using forms of words to avoid facing up to realities... I am afraid that you may get a patched-up peace and then another crisis next year." (14)

Spanish Civil War

In the 1930s the Conservative Party feared the spread of communism from the Soviet Union to the rest of Europe. Stanley Baldwin, the British prime minister, shared this concern and was fairly sympathetic to the military uprising in Spain against the left-wing Popular Front government. On the 19th July, 1936, Spain's prime minister, José Giral, sent a request to Leon Blum, the prime minister of the Popular Front government in France, for aircraft and armaments. The following day the French government decided to help and on 22nd July agreed to send 20 bombers and other arms. This news was criticized by the right-wing press and the non-socialist members of the government began to argue against the aid and therefore Blum decided to see what his British allies were going to do. (15)

Anthony Eden, the British foreign secretary, received advice that "apart from foreign intervention, the sides were so evenly balanced that neither could win." Eden warned Blum that he believed that if the French government helped the Spanish government it would only encourage Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini to aid the Nationalists. Edouard Daladier, the French war minister, was also aware that French armaments were inferior to those that Franco could obtain from the dictators. Eden later recalled: "The French government acted most loyally by us." On 8th August the French cabinet suspended all further arms sales, and four days later it was decided to form an international committee of control "to supervise the agreement and consider further action." (16)

In a speech in October, 1936, Clement Attlee described the Spanish Civil War as "a fight for the soul of Europe", charging that non-intervention had become "a farce". For the first time he stated that the government was guilty of incremental steps of appeasement. If Britain had stood firm against Mussolini over Abyssinia, there would not have been this trouble in Spain. He argued there had been "no policy in foreign affairs except the policy of giving way. The result of that is a world in anarchy." The government's policy "has not brought us nearer peace but has brought us closer and closer to the danger of war." (17)

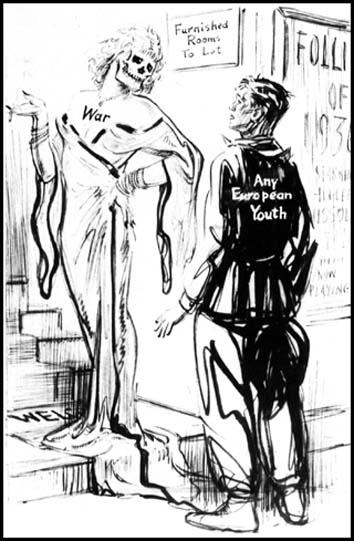

you right. I used to know your Daddy,

New York Daily News (25th April, 1936)

Attlee argued for intervention against the fascists. However, he was aware that the problem with intervention was the danger of escalating the conflict to a general European war against the fascist powers. With the encouragement of Attlee, the Labour's 1936 conference in Edinburgh condemned non-intervention and demanded that the British government restore to the Spanish government its right to buy arms. In a letter to his brother Tom in April 1937, he wrote that "I'm afraid there's no doubt about the strong pro-Franco attitude of many of the government." (18)

In a speech in October, 1936, Clement Attlee argued that if Britain had stood firm against Mussolini over Abyssinia, there would not have been this trouble in Spain. He went on to say that there had been "no policy in foreign affairs except the policy of giving way. The result of that is a world in anarchy." The government's policy "has not brought us nearer peace but has brought us closer and closer to the danger of war." (19)

Neville Chamberlain and Appeasement

On 28th May, 1937, Stanley Baldwin resigned and replaced by Neville Chamberlain. As Chancellor of the Exchequer he had resisted attempts to increase defence spending. He now changed his mind and asked the defence policy requirements committee to look at different ways of funding this expenditure. It was suggested that £1.1 billion was financed through increased taxation and £400 million coming from increased government borrowing. It was suggested that of this sum, £80 million should be spent in air-raid precautions. (20)

Over the next two years Chamberlain's Conservative government became associated with the foreign policy that later became known as appeasement. Chamberlain believed that Germany had been badly treated by the Allies after it was defeated in the First World War. He therefore thought that the German government had genuine grievances and that these needed to be addressed. He also thought that by agreeing to some of the demands being made by Adolf Hitler of Germany and Benito Mussolini of Italy, he could avoid a European war. (21)

Joachim von Ribbentrop was ambassador to London in August, 1936. His main objective was to persuade the British government not to get involved in Germany territorial disputes and to work together against the the communist government in the Soviet Union. During this period Von Ribbentrop told Hitler that the British "were so lethargic and paralyzed that they would accept without complaint any aggressive moves by Nazi Germany." (22)

According to Christopher Andrew, the author of Defence of the Realm: The Authorised History of MI5 (2010) MI5 was receiving information from a diplomat by the name of Wolfgang zu Putlitz, who was working in the German Embassy in London. Putlitz told MI5 that "He (Ribbentrop) regarded Mr Chamberlain as pro-German and said he would be his own Foreign Minister. While he would not dismiss Mr Eden he would deprive him of his influence at the Foreign Office. Mr Eden was regarded as an enemy of Germany." Putlitz constantly provided clear warnings that negotiations with Hitler and Rippentrop were likely to be fruitless and the only way to deal with Nazi Germany was to stand firm. Putlitz told MI5 that her policy of appeasement was "letting the trump cards fall out of her hands. If she had adopted, or even now adopted, a firm attitude and threatened war, Hitler would not succeed in this kind of bluff". (23)

A few weeks before he officially became prime minister, Chamberlain arranged for Nevile Henderson to replace Eric Phipps as British ambassador to Berlin. Phipps had been warning of the dangers of Hitler and in his reports he gave ample and frequent warning of Nazi intentions to his superiors in London. He argued that Germany could only be contained "through accelerated and extensive British rearmament". (24) Chamberlain urged Henderson to "take the line of co-operation with Germany". (25)

Henderson later recalled that Chamberlain "outlined to me his views on general policy towards Germany, and I think I may honestly say that to the last and bitter end I followed the general line which he set me." (26) There was some concern in the Foreign Office about the appointment of Henderson as some saw him as a political extremist and a supporter of Hitler. Oliver Harvey wrote in his diary: "I hope we are not sending another Ribbentrop to Berlin." (27)

Before leaving for Nazi Germany, Henderson read a copy of Hitler's Mein Kampf. "Though it was in parts turgid and prolix and would have been more readable if it had been condensed to a third of its length, it struck me at the time as a remarkable production on the part of a man whose education and political experience appeared to have been as slight, on his own showing, as Herr Hitler's." (28)

On 1st June, 1937, Henderson attended a banquet arranged by the German-English Society of Berlin. A large number of leading Nazis were in attendance when he made a speech where he defended Adolf Hitler and urged the British people to "lay less stress on Nazi dictatorship and much more emphasis on the great social experiment which is being tried out in this country." (29)

This speech provoked an uproar and some left-wing journalists described him as "our Nazi ambassador at Berlin". However, some newspaper editors, including Geoffrey Dawson, the editor of The Times, supported this approach to Nazi Germany. In the House of Commons the Conservative Party MP, Alfred Knox offered congratulations "to HM Ambassador in Berlin on having made a real contribution to the cause of peace". (30) Richard Griffiths, the author of Fellow Travellers of the Right (1979), has pointed out that "Henderson was not just an eccentric individual, as has been suggested; he stands as an example of a whole trend in British thought at the time." (31)

Some senior figures at MI5 were very opposed to appeasement and supplied Neville Chamberlain with a document from a spy close to Hitler quoting him as saying: "If I were Chamberlain I would not delay for a minute to prepare my country in the most drastic way for a total war... It is astounding how easy the democracies make it for us to reach our goal....If the information which has proved generally reliable and accurate in the past is to be believed, Germany is at the beginning of a Napoleonic era and her rulers contemplate a great expansion of German power." (32)

Lord Halifax, the leader of the House of Lords, shared Chamberlain's belief in appeasement. In 1936 Halifax visited Nazi Germany for the first time. Halifax's friend, Henry (Chips) Channon, reported that: "I had a long conversation with Lord Halifax about Germany and his recent visit. He described Hitler's appearance, his khaki shirt, black breeches and patent leather evening shoes. He told me he liked all the Nazi leaders, even Goebbels, and he was much impressed, interested and amused by the visit. He thinks the regime absolutely fantastic, perhaps even too fantastic to be taken seriously. But he is very glad that he went, and thinks good may come of it. I was riveted by all he said, and reluctant to let him go." (33)

Halifax later explained in his autobiography, Fullness of Days (1957): "The advent of Hitler to power in 1933 had coincided with a high tide of wholly irrational pacifist sentiment in Britain, which caused profound damage both at home and abroad. At home it immensely aggravated the difficulty, great in any case as it was bound to be, of bringing the British people to appreciate and face up to the new situation which Hitler was creating; abroad it doubtless served to tempt him and others to suppose that in shaping their policies this country need not be too seriously regarded." (34)

There were other powerful figures who supported appeasement. During the weekend of 23rd October 1937, Nancy Astor and her husband, Waldorf Astor, had thirty people to lunch. This included Geoffrey Dawson (editor of The Times), Nevile Henderson (Ambassador to Berlin), Edward Algernon Fitzroy (Speaker of the Commons), Sir Alexander Cadogan (soon to replace the anti-appeasement Robert Vansittart as Permanent Under-Secretary at the Foreign Office), Lord Lothian and Lionel Curtis. This group was known as the Cliveden Set.

According to Norman Rose, Lothian gave a talk on future relations with Adolf Hitler. "He wished to define what Britain would not fight for. Certainly not for the League of Nations, a broken vessel; nor to honour the obligations of others. As he had explained to the Nazi leaders, 'Britain had no primary interests in eastern Europe,' areas that fell within 'Germany's sphere'. To be dragged into a conflict not of Britain's making and not in defence of its vital interests would bedevil relations with the Dominions, fatal for the unity of the Empire. For the Clivedenites, this was always the bottom line... In effect, Lothian was prepared to turn central and eastern Europe over to Germany." Dawson also agreed with Lothian and this was reflected in an editorial in The Times that he wrote a few days later. (35)

Anthony Eden, the foreign secretary, supported Chamberlain's appeasement policy because he believed that Britain needed time to rearm. However, as Keith Middlemas, the author of Diplomacy of Illusion: British Government and Germany, 1937-39 (1972), has pointed out: "While Eden held to the policy of keeping Germany guessing long enough to give Britain time to rearm, so that he could negotiate from a position of strength, Chamberlain, conscious of time running out, preferred to settle the outstanding accounts at once." (36)

At this stage Winston Churchill was not giving his support to those opposing the appeasement of Adolf Hitler. On 17th September, Churchill praised Hitler's domestic achievements. In an article published in The Evening Standard after highlighting Germany's achievements in the First World War he wrote: "One may dislike Hitler’s system and yet admire his patriotic achievement. If our country were defeated I hope we should find a champion as indomitable to restore our courage and lead us back to our place among the nations. I have on more than one occasion made my appeal in public that the Führer of Germany should now become the Hitler of peace." (37)

Churchill went further the following month. "The story of that struggle (Hitler's rise to power), cannot be read without admiration for the courage, the perseverance, and the vital force which enabled him to challenge, defy, conciliate or overcome, all the authority or resistances which barred his path.". He then considered the way Hitler had suppressed the opposition and set up concentration camps: "Although no subsequent political action can condone wrong deeds, history is replete with examples of men who have risen to power by employing stern, grim and even frightful methods, but who nevertheless, when their life is revealed as a whole, have been regarded as great figures whose lives have enriched the story of mankind. So may it be with Hitler." (38)

In a speech at the Conservative Party conference on 7th October, 1937, he made it clear that he opposed the government's policy on India but supported its appeasement policy: "I used to come here year after year when we had some differences between ourselves about rearmament and also about a place called India. So I thought it would only be right that I should come here when we are all agreed... let us indeed support the foreign policy of our Government, which commands the trust, comprehension, and the comradeship of peace-loving and law-respecting nations in all parts of the world." (39)

Nevile Henderson, the British ambassador to Berlin, upset Eden and Sir Robert Vansittart, his boss at the Foreign Office, by attending the annual Nuremberg Rally. (40) Henderson told Eden that he was regarded as "too pro-Nazi or pro-German". However, he believed that sometimes it was necessary to impose a dictatorship. He considered Antonio Salazar, "the present dictator of Portugal" one of the "wisest statesmen which the post-war period has produced in Europe". He argued that Hitler had probably gone too far with the Nuremberg Laws but "dictatorships are not always evil and, however anathema the principle may be to us, it is unfair to condemn a whole country, or even a whole system. because parts of it are bad." (41)

Henderson admitted in his autobiography, Failure of a Mission (1940), that his comments gave "most offence to the left wing". However, he believed that that the British people should pay more "attention to the great social experiment which was being tried out in Germany" and condemned those who suggested that "our old democracy has nothing to learn from Nazism". Henderson argued that "in fact, many things in the Nazi organisation and social institutions... which we might study and adapt to our own use with great profit both to the health and happiness of our own nation and old democracy." (42)

In November, 1937, Neville Chamberlain announced he was sending his friend, and fellow appeaser, Lord Halifax, to meet Adolf Hitler, Joseph Goebbels and Hermann Göring in Germany. Anthony Eden was furious when he discovered this and felt he was being undermined as foreign secretary. One historian has commented: "Eden and Chamberlain seemed like two horses harnessed to a cart, both pulling in different directions." (43)

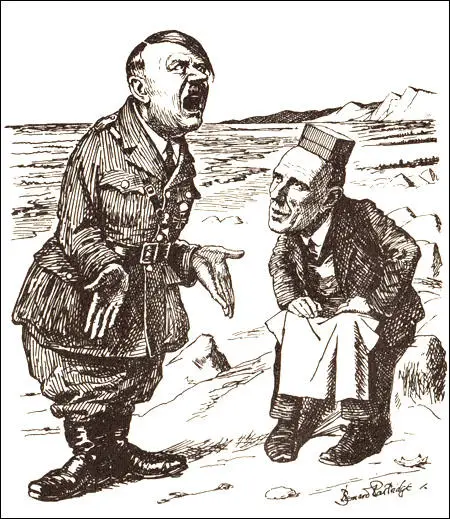

In his diary, Halifax records how he told Hitler: "Although there was much in the Nazi system that profoundly offended British opinion, I was not blind to what he (Hitler) had done for Germany, and to the achievement from his point of view of keeping Communism out of his country." This was a reference to the fact that Hitler had banned the Communist Party (KPD) in Germany and placed its leaders in Concentration Camps. Halifax told Hitler: "On all these matters (Danzig, Austria, Czechoslovakia) ... the British government... "were not necessarily concerned to stand for the status quo as today... If reasonable settlements could be reached with... those primarily concerned we certainly had no desire to block." (44)

The story was leaked to the journalist Vladimir Poliakoff. On 13th November 1937 the Evening Standard reported the likely deal between the two countries: "Hitler is ready, if he receives the slightest encouragement, to offer to Great Britain a ten-year truce in the colonial issue... In return... Hitler would expect the British Government to leave him a free hand in Central Europe". (45)

On 17th November, Claude Cockburn reported in The Week, that the deal had been first moulded "into usable diplomatic shape" at meetings of the Cliveden Set that for years has "exercised so powerful an influence on the course of British policy." He added that Lord Halifax was "the representative of Cliveden and Printing House Square rather than of more official quarters." (46)

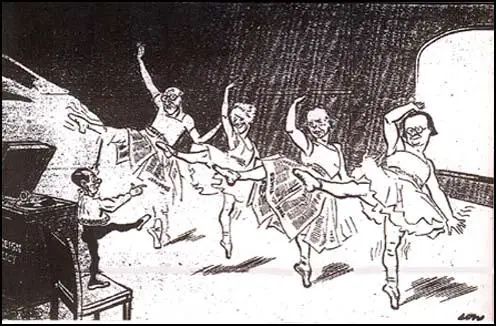

David Low, had a cartoon published showing James Garvin, Nancy Astor, Philip Henry Kerr and Geoffrey Dawson, holding high the slogan "Any Sort of Peace at Any Sort of Price". The term Cliveden Set was first used by the Reynolds News on 28th November, 1937, in an article that argued that the group were highly sympathetic to fascism. (47)

Lord Halifax later explained that Hitler told him that Czechoslovakia "only needed to treat the Germans living within her borders well and they would be entirely happy". He also had meetings with Hermann Göring, Joseph Goebbels, Hjalmar Schacht and Werner von Blomberg. Göring informed Halifax that Germany did not intend to fight to gain colonies. Blomberg said that Anglo-German relations were more important than the "colonial question" but Germany were interested in taking territory in Central Europe. (48)

Halifax wrote to Chamberlain on 24th November, 1937: "The whole thing comes back to this. However much we may dislike the idea of Nazi beaver-like propaganda etc. in Central Europe, neither we nor the French are going to be able to stop it and it would therefore seem short-sighted to forgo the chance of a German settlement by holding out for something we are almost certainly going to find ourselves powerless to secure." (49)

Resignation of Anthony Eden

Neville Chamberlain invited Konstantin von Neurath, the German foreign minister, to London. On 26th November, 1937, Chamberlain recorded his objectives in the negotiations: "It was not part of my plan that we should make, or receive, any offers. What I wanted to do was to convince Hitler of our sincerity and to ascertain what objectives he had in mind... Both Hitler and Göring said separately and emphatically that they had no desire or intention of making war and I think we may take this as correct, at any rate for the present. Of course they want to dominate Eastern Europe; they want as close a union with Austria as they can get, without incorporating her in the Reich." (50)

Anthony Eden made it clear to the prime minister that he was unwilling to force President Eduard Beneš of Czechoslovakia, to make concessions. William Strang, a senior figure in the Foreign Office, also urged caution over these negotiations: "Even if it were in our interest to strike a bargain with Germany, it would in present circumstances be impossible to do so. Public sentiment here and our existing international obligations are all against it." (51)

Nevile Henderson, who was in favour of an agreement with Hitler, warned the British government that Nazi Germany was building up its armed forces. In January 1938 he reported: "The rearmament of Germany, if it has been less spectacular because it is no longer news, has been pushed on with the same energy as in previous years. In the army, consolidation has been the order of the day, but there is clear evidence that a considerable increase is being prepared in the number of divisions and of additional tank units outside those divisions. The air force continues to expand, at an alarming rate, and one can at present see no indication of a halt. We may well soon be faced with a strength of between 4000 and 5000 first-line aircraft.... Finally, the mobilisation of the civilian population and industry for war, by means of education, propaganda, training, and administrative measures, has made further strides. Military efficiency is the god to whom everyone must offer sacrifice. It is not an army, but the whole German nation which is being prepared for war." (52)

On 4th February, 1938, Adolf Hitler sacked the moderate Konstantin von Neurath as Foreign Minister, and replaced him with the hard-line, Joachim von Ribbentrop. Eden argued that this move made it even more difficult to get an agreement with Hitler. He was also opposed to further negotiations with Benito Mussolini about withdrawing from its involvement in the Spanish Civil War. Eden stated that he completely "mistrusted" the Italian leader. (53)

At a Cabinet meeting Chamberlain made it clear that he was unwilling to back down over the issue. Anthony Eden resigned on 20th February 1938. He told the House of Commons the following day: "I do not believe that we can make progress in European appeasement if we allow the impression to gain currency abroad that we yield to constant pressure. I am certain in my own mind that progress depends above all on the temper of the nation, and that temper must find expression in a firm spirit. This spirit I am confident is there. Not to give voice it is I believe fair neither to this country nor to the world." (54)

No one else in the Cabinet was willing to resign over this issue: Winston Churchill commented: "There seemed one strong young figure standing up against long, dismal, drawling tides of drift and surrender, or wrong measurements and feeble impulses. He seemed at this moment to embody the life-hope of the British nation… Now he was gone." (55) Robert Boothby, commented that the "Conservative Party was rotten at the core. The only thing they cared about was their property and their cash. The only thing they feared was that one day those nasty Communists would come and take it." (56)

Churchill argued in Parliament that: "The resignation of the late Foreign Secretary may well be a milestone in history. Great quarrels, it has been well said, arise from small occasions but seldom from small causes. The late Foreign Secretary adhered to the old policy which we have all forgotten for so long. The Prime Minister and his colleagues have entered upon another and a new policy. The old policy was an effort to establish the rule of law in Europe, and build up through the League of Nations effective deterrents against the aggressor. Is it the new policy to come to terms with the totalitarian Powers in the hope that by great and far-reaching acts of submission, not merely in sentiment and pride, but in material factors, peace may be preserved." (57)

David Low, a cartoonist who opposed appeasement, commented: "As might have been expected in such conditions, advocates of Churchill-Eden and opponents of appeasement soon found themselves labeled war-mongers and irresponsibles." Chamberlain made a speech where he attacked "the bitter cartoons of Low" in the Evening Standard and that this had upset Adolf Hitler to such an extent that it was harming negotiations with the Nazi government. (58)

On 12th March, 1938, the German Army invaded Austria. The country had been due to hold a referendum on its independence in which, it was expected, it would vote against incorporation into the Third Reich. The union with Austria was achieved by bullying and intimidation, but without a single shot being fired. Chamberlain was shocked and dismayed but felt he had to accept Anschluss. He told the cabinet that they now had to "prevent an occurrence of similar events in Czechoslovakia". (59)

Winston Churchill, like the Government and most of his fellow Conservative MPs, decided that they would have to accept the aggressive action taken by Hitler. During the debate in the House of Commons, Churchill did not advocate the use of force to remove German forces from Austria. Instead he called for was discussion between diplomats at Geneva and still continued to support the government's appeasement policy. (60)

According to John Bew, there were political reasons for this approach and why Clement Attlee led the attack on Chamberlain's decision not to take action over Austria. "Churchill could do very little on his own. The majority of his party remained firmly behind Chamberlain. In public, Churchill had in fact begun to temper his criticism of the government, in the hope that he might be brought back into office in some capacity, and be able to exert his influence from within. It was Attlee... who led the criticism of the government in Parliament." (61)

Czechoslovakia

Chamberlain now appointed fellow appeaser, Lord Halifax, as his new foreign secretary. Nevile Henderson, the British ambassador in Berlin, told Chamberlain that we would lose a war with Nazi Germany. Hitler's main concern was over Czechoslovakia, a country that had been created after the allied victory in the First World War. Before the conflict it had been part of the Austrian-Hungarian empire. The population consisted of Czechs (51%), Slovaks (16%), Germans (22%), Hungarians (5%) and Rusyns (4%).

Lord Halifax recommended that the British government should apply pressure on President Eduard Beneš of Czechoslovakia to give up the Sudetenland, with its largely German-speaking population, to Germany. Henderson's biographer, Peter Neville, pointed out: "So strong was this conviction that he sometimes erred on the side of prejudice against the Czechs and their president, Beneš". (62)

In March 1938, Adolf Hitler advised Konrad Henlein, the leader of the Sudeten Germans, on his political campaign. Hitler told him "that demands should be made by the Sudeten German Party which are unacceptable to the Czech government." Henlein later summarised the comments: "We must always demand so much that we can never be satisfied." Hitler suggested that once a crisis was established, he would be willing to send German troops into Czechoslovakia. (63)

Later that month, Hugh Christie, an MI6 agent, working in Nazi Germany, told headquarters that Hitler would be ousted by the military if Britain joined forces with Czechoslovakia against Germany. Christie warned that the "crucial question is: How soon will the next step against Czechoslovakia be tried?... The probability is that the delay will not exceed two or three months at most, unless France and England provide the deterrent, for which cooler heads in Germany are praying." (64)

Chamberlain believed his appeasement policy was very popular with the British people. Lord Beaverbrook, the owner of the highest selling newspaper in Britain told the former Canadian Prime Minister Richard B. Bennett, that Chamberlain was "the best P.M. we've had in half a century... dominating Parliament but the country has not yet taken to him." If he wished, claimed Beaverbrook, he could "be Prime Minister for the rest of his life." Chamberlain told his sister that "as for the House of Commons there can be no question that I have got the confidence of our people as Stanley Baldwin never had it." (65)

However, some members of his cabinet found him a difficult man. Philip Cunliffe-Lister (Lord Swinton), the Secretary of State for Air, criticised Chamberlain as "overly autocratic and intolerant of criticism". He became suspicious to the point of paranoia, employing Sir Joseph Ball, with the support of MI5, to gather information on the contacts and financial arrangements of his political opponents, and even to intercept their telephone calls. (66) Stanley Baldwin complained to Anthony Eden that his own work "in keeping politics national instead of party" had been rendered worthless. Eden replied that Chamberlain was attempting to "return to class warfare in its bitterest form". (67)

The Czech crisis reached the first of many dangerous points in May 1938. It was reported that two Sudeten German motorcyclists had been shot dead by the Czech police. This led to rumours of Hitler preparing to use the incident as a pretext for invasion and there were reports of German troops assembling near the Czech border. The French and Soviet governments pledged support to the Czechs. Lord Halifax sent a message to Berlin which warned that if force was used Germany "could not count upon this country being able to stand aside". At the same time he sent a diplomatic message which told the French they should not assume Britain would fight to save Czechoslovakia. (68)

On 25th May, Lord Halifax had a meeting Tomas Masaryk, the Czechoslovak minister in London, and told him the least that his country could "get away with" would be autonomy on "the Swiss model" combined with neutrality in foreign policy. Later that day Chamberlain told the Cabinet "the Sudeten Deutsch should remain in Czechoslovakia but as contented people." He made the same point that Halifax had made to Masaryk, when he said if Czechoslovakia became a neutral state "it might be possible to get a settlement in Europe." (69) Five days later, Hitler made a speech where he stated: "It is my unalterable decision to smash Czechoslovakia by military action in the near future." (70)

Chicago Times (8th September, 1938)

Winston Churchill now decided to become involved in discussions with representatives of Hitler's government in Nazi Germany in an attempt to avoid conflict between the two nations. In July, 1938, Churchill had a meeting with Albert Forster, the Nazi Gauleiter of Danzig. Forster asked Churchill whether German discriminatory legislation against the Jews would prevent an understanding with Britain. Churchill replied that he thought "it was a hindrance and an irritation, but probably not a complete obstacle to a working agreement." (71)

On the suggestion of Lord Halifax it was decided to send Lord Runciman, to Czechoslovakia to investigate the Sudeten claims for self-determination. He arrived in Prague on 4th August 1938, and over the next few days he saw all the major figures involved in the dispute within Czechoslovakia. He became extremely sympathetic to the Sudeten desire for home rule. In his report he placed the major share of the blame for the breakdown of talks on the Czech government and recommended that the Sudeten Germans be allowed the opportunity to join the Third Reich. Neville Henderson supported Runciman and told Chamberlain: "However, badly Germany behaves does not make the rights of the Sudeten any less justifiable." (72)

A group of anti-Nazi Germans, holding high office, including Admiral Wilhelm Canaris, Colonel-General Ludwig Beck, and Carl Goerdeler, sent Major Ewald von Kleist-Schmenzin to London as their emissary to warn Chamberlain of Hitler's plans to invade Czechoslovakia, and later to attack France and eventually the Soviet Union. Kleist-Schmenzin argued that only a strong Anglo-French line would force Hitler to back down. Chamberlain rejected these views because they conflicted with his own view that open threats of force would hasten the outbreak of war. (73)

References

(1) Winston Churchill, speech in the House of Commons (24th October 1935)

(2) Winston Churchill, speech (17th February, 1933)

(3) Winston Churchill, The Sunday Chronicle (26th May, 1935)

(4) Trevor Burridge, British Labour & Hitler's War (1976) pages 17-18

(5) Michael Jago, Clement Attlee (2017) page 104

(6) Clement Attlee, speech (1st October, 1935)

(7) Sydney Silverman, Report of the 36th Labour Party Annual Conference (1935) page 196

(8) Ernest Bevin, Report of the 36th Labour Party Annual Conference (1935) page 204

(9) Clement Attlee, letter to Tom Attlee (26th October, 1936)

(10) Alan Bullock, Hitler: A Study in Tyranny (1962) page 345

(11) Frank McDonough, Neville Chamberlain, Appeasement and the British Road to War (1998) page 27

(12) Winston Churchill, The Evening Standard (13th March, 1936)

(13) Winston Churchill, speech in the House of Commons (6th April, 1936)

(14) Clement Attlee, speech in the House of Commons (26th March, 1936)

(15) Patricia Knight, The Spanish Civil War (1998) page 67

(16) Antony Beevor, The Spanish Civil War (1982) page 110

(17) Clement Attlee, speech in the House of Commons (29th October, 1936)

(18) Francis Beckett, Clem Attlee (2000) page 134

(19) Clement Attlee, speech in the House of Commons (29th October, 1936)

(20) Frank McDonough, Neville Chamberlain, Appeasement and the British Road to War (1998) page 40

(21) Andrew J. Crozier, Nevile Henderson : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(22) Louis L. Snyder, Encyclopedia of the Third Reich (1998) page 296

(23) Christopher Andrew, Defence of the Realm: The Authorised History of MI5 (2010) page 199

(24) G. T. Waddington, Eric Phipps : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(25) Keith Middlemas, Diplomacy of Illusion: British Government and Germany, 1937-39 (1972) page 53

(26) Neville Henderson, Failure of a Mission (1940) page 17

(27) Keith Middlemas, Diplomacy of Illusion: British Government and Germany, 1937-39 (1972) page 74

(28) Neville Henderson, Failure of a Mission (1940) page 14

(29) Neville Henderson, speech in Berlin (1st June, 1937)

(30) Alfred Knox, speech in House of Commons (9th June 1937)

(31) Richard Griffiths, Fellow Travellers of the Right (1979) page 283

(32) Jim Wilson, Nazi Princess: Hitler, Lord Rothermere and Princess Stephanie Von Hohenlohe (2011) page 82

(33) Henry (Chips) Channon, diary entry (5th December, 1936)

(34) Lord Halifax, Fullness of Days (1957) page 181

(35) Norman Rose, The Cliveden Set: Portrait of an Exclusive Fraternity (2000) pages 169-173

(36) Keith Middlemas, Diplomacy of Illusion: British Government and Germany, 1937-39 (1972) page 74

(37) Winston Churchill, The Evening Standard (17th September 1937)

(38) Winston Churchill, The Evening Standard (14th October, 1937)

(39) Winston Churchill, speech at the Conservative Party conference at Scarborough (14th October, 1937)

(40) Peter Neville, Nevile Henderson : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(41) Neville Henderson, Failure of a Mission (1940) page 21

(42) Neville Henderson, Failure of a Mission (1940) page 23

(43) Keith Middlemas, Diplomacy of Illusion: British Government and Germany, 1937-39 (1972) page 138

(44) Lord Halifax, diary entry (19th November, 1937)

(45) The Evening Standard (13th November 1937)

(46) Claude Cockburn, The Week (17th November, 1937)

(47) Reynolds News (28th November, 1937)

(48) Frederick Smith, Life of Lord Halifax (1965) page 366

(49) Lord Halifax, letter to Neville Chamberlain (24th November, 1937)

(50) Neville Chamberlain, memorandum (26th November, 1937)

(51) William Strang, memorandum (November, 1937)

(52) Neville Henderson, report to the British government (January 1938)

(53) Keith Middlemas, Diplomacy of Illusion: British Government and Germany, 1937-39 (1972) page 151

(54) Anthony Eden, speech (21st February 1938)

(55) Winston Churchill, The Gathering Storm (1950) page 257

(56) Robert Boothby, Boothby: Recollections of a Rebel (1978)

(57) Winston Churchill, speech in the House of Commons (22nd February, 1938)

(58) David Low, Autobiography (1956) page 312

(59) Frank McDonough, Neville Chamberlain, Appeasement and the British Road to War (1998) page 58

(60) Winston Churchill, speech in the House of Commons (12th March, 1938)

(61) John Bew, Citizen Clem: A Biography of Attlee (2016) page 222

(62) Peter Neville, Nevile Henderson : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(63) Robert A. Parker, Chamberlain and Appeasement (1993) page 147

(64) Hugh Christie, report to MI6 (March, 1938)

(65) Donald Cameron Watt, How War Came: Immediate Origins of the Second World War (1989) page 78

(66) Anthony Eden, letter to Stanley Baldwin (11th May, 1938)

(67) David Faber, Munich: The 1938 Appeasement Crisis (2008) pages 169-170

(68) Frank McDonough, Neville Chamberlain, Appeasement and the British Road to War (1998) page 61

(69) Robert A. Parker, Chamberlain and Appeasement (1993) page 149

(70) Adolf Hitler, speech (30th May, 1938)

(71) Clive Ponting, Winston Churchill (1994) page 394

(72) Frank McDonough, Neville Chamberlain, Appeasement and the British Road to War (1998) pages 61-62

(73) Richard Lamb, The Ghosts of Peace (1987) pages 2-5

John Simkin