Herbert Matthews

Herbert Matthews was born in New York City on 10th January, 1900. He had volunteered for service in the First World War but reached the Western Front too late to take part in the fighting.

On his return to the United States he studied languages at Columbia University and ended up with a command of Italian, French and Spanish. After graduating in 1922 he joined the New York Times as a secretary to the Business Manager of the newspaper. According to Time Magazine: "After three years in the business office, he switched to the news department. A reluctant journalist, who still has a tendency to be ponderous and pontifical, he spent much of the next ten years longing to get back to his books (Dante, medieval history)."

In 1931 Matthews was sent by the newspaper to work at the Paris Bureau. It was from here that he was dispatched to cover the Italian invasion of Ethiopia in 1935. Matthews later wrote: "If you start from the premise that a lot of rascals are having a fight, it is not unnatural to want to see the victory of the rascal you like, and I liked the Italians during that scrimmage more than I did the British or the Abyssinians." He later admitted: "The right or the wrong of it did not interest me greatly." This attitude resulted in him being labeled a "fascist".

Paul Preston, the author of We Saw Spain Die: Foreign Correspondents in the Spanish Civil War (2008), has argued: "Matthews returned to Paris, where his early articles on the French response to the Spanish Civil War were not notably sympathetic to the Republic." In March 1937 the New York Times sent Matthews to Spain to cover the Spanish Civil War.

Based in Madrid he found the life very exciting: "Of all places to be in the world, Madrid is the most satisfactory. I thought so from the moment I arrived, and whenever I am away from it these days I cannot help longing to return. All of us feel the same way, so it is more than a personal impression. The drama, the thrills, the electrical optimism, the fighting spirit, the patient courage of these mad and wonderful people - these are things worth living for and seeing with one's own eyes."

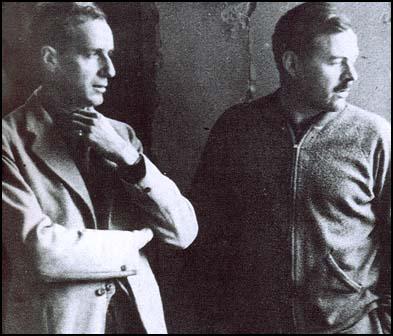

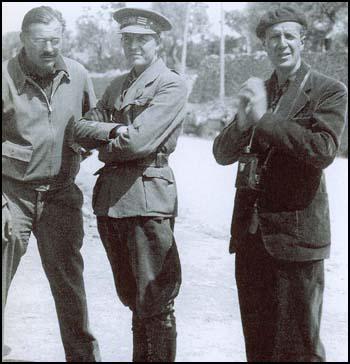

Matthews spent a lot of time with Ernest Hemingway in Spain. Alvah Bessie met them at Ebro: "One was tall, thin, dressed in brown corduroy, wearing horn-shelled glasses. He had a long, ascetic face, firm lips, a gloomy look about him. The other was taller, heavy, red-faced, one of the largest men you will ever see; he wore steel-rimmed glasses and a bushy mustache. These were Herbert Matthews of The New York Times and Ernest Hemingway, and they were just as relieved to see us as we were to see them."

Although he arrived with little sympathy for the Popular Front government. Constancia de la Mora, who worked with Herbert Matthews in Spain, remarked: "Tall, lean, and lanky, Matthews was one of the shyest, most diffident men in Spain. He used to come in every evening, always dressed in his gray flannels, after arduous and dangerous trips to the front, to telephone his story to Paris, whence it was cabled to New York... For months he would not come near us except to telephone his stories - for fear, I suppose, that we might influence him somehow. He was so careful; he used to spend days tracking down some simple fact - how many churches in such and such a small town; what the Government's agricultural program was achieving in this or that region. Finally, when he discovered that we never tried to volunteer any information, even to the point of not offering him the latest press release unless he specifically requested it, he relaxed a little. Matthews had his own car and he used to drive to the front more often than almost any other reporter. We had to sell him the gasoline from our own restricted stores, and he was always running out of his monthly quota. Then he used to come to my desk, very shy, to beg for more. And we always tried to find it for him: both because we liked and respected him and because we did not want the New York Times correspondent to lack gasoline to check the truth of our latest news bulletin."

As Time Magazine pointed out: "When he got to Spain, his first lesson began to sink in: Fascism was designed for export, and anybody who did not want to import it must fight it. Somewhere between Valencia, blitzed Barcelona and Madrid, his ivory tower crumbled, and Matthews stepped from its rubble to do the best reporting of his career. Because it was also optimistic reporting, he wound up feeling as sick at heart as the Spanish Republicans."

Herbert Matthews was highly critical of the Non-Intervention policy of President Franklin D. Roosevelt: "He (Roosevelt) was too intelligent and experienced to fool himself about the moral issues involved" and that his "overriding consideration was not what was right or wrong, but what was best for the United States and, incidentally, for himself and the Democratic Party."

After the defeat at Ebro, Matthews left Spain: "The story that I told - of bravery, of tenacity, of discipline and high ideals - had been scoffed at by many. The dispatches describing the callousness of the French and the cynicism of the British had been objected to and denied. I, too, was beaten and sick at heart and somewhat shell-shocked, as any person must be under the nerve strain of seven weeks of incessant danger, coming at the end of two years' campaigning... But the lessons I had learned! They seemed worth a great deal. Even then, heartsick and discouraged as I was, something sang inside of me. I, like the Spaniards, had fought my war and lost, but I could not be persuaded that I had set too bad an example."

Herbert Matthews wrote at the end of the Spanish Civil War: "I know, as surely as I know anything in this world, that nothing so wonderful will ever happen to me again as those two and a half years I spent in Spain. And it is not only I who say this, but everyone who lived through that period with the Spanish Republicans. Soldier or journalist, Spaniard or American or British or French or German or Italian, it did not matter. Spain was a melting pot in which the dross came out and pure gold remained. It made men ready to die gladly and proudly. It gave meaning to life; it gave courage and faith in humanity; it taught us what internationalism means, as no League of Nations or Dumbarton Oaks will ever do. There one learned that men could be brothers, that nations and frontiers and races were but outer trappings, and that nothing counted, nothing was worth fighting for, but the idea of liberty."

Over the next few years he published Eyewitness in Abyssinia (1937), Two Wars and More to Come (1938) and The Fruits of Fascism (1943). During the Second World War Matthews served as the Rome correspondent for the New York Times. He also reported the war from India from July 1942 to July 1943. In 1945 he headed the London Bureau of the newspaper.

At the end of the war Matthews stated: "The democracies and the Communist power facing each other over the stricken field of Fascism. They need not settle their differences by war... But war, as we have learned to our sorrow, is not avoided by appeasement; it is avoided by possessing the strength to hold your own and by using that strength for political purposes."

In 1949 Matthews joined the Editorial Board of the New York Times. Matthews took a keen interest in Latin America and wrote numerous articles and editorials on the subject. In 1957 Ruby Phillips, the Bureau Chief in Havana, arranged for Matthews to interview Fidel Castro in the Sierra Maestra. In the interview Castro spoke about his plans to overthrow Fulgencio Batista.

In July 1959 Matthews returned to Cuba. His reporting of events caused a great deal of controversy: "This is not a Communist revolution in any sense of the word, and there are no Communists in positions of control... Even the agrarian reform, Cubans point out with irony, is not at all what the Communists were suggesting, for it is far more radical and drastic than the Reds consider wise as a first step to the collectivization they, but not the Cubans, want." This was in contrast to the views of Ruby Phillips, who also worked for the New York Times: "Since the victory of the Castro revolution last January, the Communists and the 26th of July movement have been in close cooperation."

Matthews retired from the New York Times in 1967. Two years later, he published Fidel Castro: A Political Biography (1969). His autobiography, A World in Revolution: A Newspaperman's Memoir, was published in 1972. This was followed by Revolution in Cuba (1975).

Herbert Matthews died in Adelaide, South Australia, on 30 July 1977.

Primary Sources

(1) Herbert Matthews, Two Wars and More to Come (1938)

Of all places to be in the world, Madrid is the most satisfactory. I thought so from the moment I arrived, and whenever I am away from it these days I cannot help longing to return. All of us feel the same way, so it is more than a personal impression. The drama, the thrills, the electrical optimism, the fighting spirit, the patient courage of these mad and wonderful people - these are things worth living for and seeing with one's own eyes.

(2) Paul Preston, We Saw Spain Die: Foreign Correspondents in the Spanish Civil War (2008)

In May 1936, Matthews returned to Paris, where his early articles on the French response to the Spanish Civil War were not notably sympathetic to the Republic. Nevertheless, he became sufficiently fascinated by events in Spain that he asked for, and received, a posting there after Carney's abandonment of Republican Spain. Despite arriving with sympathies for the Italians, Matthews would write during the Spanish Civil War: "No one who knows what is happening here and who has any pretense to intellectual honesty can forbear to take sides."

(3) Constancia de la Mora, In Place of Splendor (1939)

Tall, lean, and lanky, Matthews was one of the shyest, most diffident men in Spain. He used to come in every evening, always dressed in his gray flannels, after arduous and dangerous trips to the front, to telephone his story to Paris, whence it was cabled to New York... For months he would not come near us except to telephone his stories - for fear, I suppose, that we might influence him somehow. He was so careful; he used to spend days tracking down some simple fact - how many churches in such and such a small town; what the Government's agricultural program was achieving in this or that region. Finally, when he discovered that we never tried to volunteer any information, even to the point of not offering him the latest press release unless he specifically requested it, he relaxed a little. Matthews had his own car and he used to drive to the front more often than almost any other reporter. We had to sell him the gasoline from our own restricted stores, and he was always running out of his monthly quota. Then he used to come to my desk, very shy, to beg for more. And we always tried to find it for him: both because we liked and respected him and because we did not want the New York Times correspondent to lack gasoline to check the truth of our latest news bulletin.

(4) Herbert Matthews, The Education of a Correspondent (1946)

The story that I told - of bravery, of tenacity, of discipline and high ideals - had been scoffed at by many. The dispatches describing the callousness of the French and the cynicism of the British had been objected to and denied. I, too, was beaten and sick at heart and somewhat shell-shocked, as any person must be under the nerve strain of seven weeks of incessant danger, coming at the end of two years' campaigning. For a few years afterwards I suffered from a form of claustrophobia, brought on by being caught, as in a vise, in a refuge in Tarragona during one of the last bombings. So I was depressed, physically and mentally and morally... But the lessons I had learned! They seemed worth a great deal. Even then, heartsick and discouraged as I was, something sang inside of me. I, like the Spaniards, had fought my war and lost, but I could not be persuaded that I had set too bad an example.

(5) John Gates, The Story of an American Communist (1959)

I was now with a group of three. We ran into a fascist foot patrol but got away successfully into the brush. Deciding now that it was unsafe to move by daylight, we hid and went to sleep, and moved only under cover of the dark. That night we reached the river near the town of Mora del Ebro. We could find no boats, no materials with which to build a raft. Coming upon a small house, we decided to go in. I was leading the way, grenade in hand, when from inside came a call: "Who's there?" My impulse was to throw the grenade and run, but I was suddenly struck by the realization that the words had been spoken in English and the voice sounded like George Watt, who had been in the rear of our column the previous night. I answered "It's me." Sure enough out came George and several other of our men. They had bedded down for the night-very foolishly, I thought, in view of how close they had come to being killed by their own men. Watt told me later that his group had come just as close to opening fire on us. It made a good story to tell afterwards, and a never-settled debate on which of us had been more unwise.

The river was very wide at this point and the current swift. Some of the men were not sure they could make it, so fatigued were we all, but we decided to join forces and swim across at dawn. We stripped naked, threw away all our belongings, and made for the opposite bank. Three of us got across safely just as the day was beginning to break. The bodies of two other men were washed up on the shore several days later. Besides myself, those who made it were Watt and Joseph Hecht, who was later killed in World War II. In the excitement I had kept my hat on.

Between the river and the road stretched a field of cockleburrs which we now crossed on our bare, bruised feet. This was the last straw: naked (except for my hat), hungry and exhausted, I felt I could not take another step. I had sworn never to surrender to the fascists but I told Watt that if they came along just then, I would give up (actually, we would not have had much choice, having no arms).

We lay down on the side of the road, with no idea of who might come along, too beat to care much. Suddenly a car drove up, stopped and out stepped two men. Nobody ever looked better to me in all my life-they were Ernest Hemingway and New York Times correspondent Herbert Matthews. We hugged one another, and shook hands. They told us everything they knew - Hemingway, tall and husky, speaking in explosions; Matthews, just as tall but thin, and talking in his reserved way. The main body of the Loyalist army, it seems, had crossed the Ebro, and was now regrouping to make a stand on this side of the river. The writers gave us the good news of the many friends who were safe, and we told them the bad news of some who were not. Facing the other side of the river, Hemingway shook his burly fist. "You fascist bastards haven't won yet," he shouted. "We'll show you!"

We rejoined the 15th Brigade, or rather the pitiful remnants of it. Many were definitely known to be dead, others missing. Men kept trickling across the Ebro, straggling in for weeks afterwards, but scores had been captured by the fascists. During the first few days, I took charge of what was left of the Lincoln Battalion; we were dazed and still tense from our experience. Meanwhile, the enemy conducted air raids daily against our new positions, but we were well scattered and the raids caused more fear than damage.

(6) Alvah Bessie, Men in Battle (1939)

At Ebro... the country was so mountainous it looked as though a few machine-guns could have held off a million men. We came back down, went up side roads, crossroads, through small towns, and on a hillside near Rasquera we found three of our men: George Watt and John Gates (then adjutant Brigade Commissar), Joe Hecht. They were lying on the ground wrapped in blankets; under the blankets they were naked. They told us they had swum the Ebro early that morning; that other men had swum and drowned; that they did not know anything of Merriman or Doran, thought they had been captured. They had been to Gandesa, had been cut off there, had fought their way out, travelled at night, been sniped at by artillery. You could see they were reluctant to talk, and so we just sat down with them. Joe looked dead.

Below us there were hundreds of men from the British, the Canadian Battalions; a food truck had come up, and they were being fed. A new Matford roadster drove around the hill and stopped near us, and two men got out we recognized. One was tall, thin, dressed in brown corduroy, wearing horn-shelled glasses. He had a long, ascetic face, firm lips, a gloomy look about him. The other was taller, heavy, red-faced, one of the largest men you will ever see; he wore steel-rimmed glasses and a bushy mustache. These were Herbert Matthews of The New York Times and Ernest Hemingway, and they were just as relieved to see us as we were to see them. We introducd ourselves and they asked questions. They had cigarettes; they gave us Lucky Strikes and Chesterfields. Matthews seemed to be bitter; permanently so.

Hemingway was eager as a child, and I smiled remembering the first time I had seen him, at a Writers' Congress in New York. He was making his maiden public speech, and when it didn't read right, he got mad at it, repeating the sentences he had fumbled, with exceptional vehemence. Now he was like a big kid, and you liked him. He asked questions like a kid: "What then? What happened then? And what did you do? And what did he say? And then what did you do?" Matthews said nothing, but he took notes on a folded sheet of paper. "What's your name?" said Hemingway; I told him. "Oh," he said, "I'm awful glad to see you; I've read your stuff." I knew he was glad to see me; it made me feel good, and I felt sorry about the times I had lambasted him in print; I hoped he had forgotten them, or never read them. "Here," he said, reaching in his pocket. "I've got more." He handed me a full pack of Lucky Strikes.

(7) Herbert Matthews, The Education of a Correspondent (1946)

I have already lived six years since the Spanish Civil War ended, and have seen much of greatness and glory and many beautiful things and places since then, and I may, with luck, live another twenty or thirty years, but I know, as surely asp I know anything in this world, that nothing so wonderful will ever happen to me again as those two and a half years I spent in Spain. And it is not only I who say this, but everyone who lived through that period with the Spanish Republicans. Soldier or journalist, Spaniard or American or British or French or German or Italian, it did not matter. Spain was a melting pot in which the dross came out and pure gold remained. It made men ready to die gladly and proudly. It gave meaning to life; it gave courage and faith in humanity; it taught us what internationalism means, as no League of Nations or Dumbarton Oaks will ever do. There one learned that men could be brothers, that nations and frontiers and races were but outer trappings, and that nothing counted, nothing was worth fighting for, but the idea of liberty.

(8) Time Magazine (17th June, 1946)

Long-faced Herbert Lionel Matthews, 46, is the kind of correspondent who makes the New York Times proud of its foreign-news coverage. Seasoned by a decade of wars (in Ethiopia, Loyalist Spain, Italy, India, France), he holds a top job on the biggest staff (55 men) that any U.S. newspaper maintains abroad. His bosses know their London bureau head as a deadly serious, high-strung reporter who makes his share of wrong guesses, but strives to make sense for tomorrow's historians as well as today's cable editors...

In 1922 Herbert Matthews, a bookish youth with a new Phi Beta Kappa key (Columbia University), answered a blind want ad in the New York Times for a secretary. The advertiser turned out to be the Times itself. After three years in the business office, he switched to the news department. A reluctant journalist, who still has a tendency to be ponderous and pontifical, he spent much of the next ten years longing to get back to his books (Dante, medieval history). Even when he became second man in the Times's Paris bureau, he writes ruefully, he stuck to his ivory tower, picked up no political knowledge that he could avoid, shut his eyes to the drama of his own century.

But a decade ago he began to learn. From Marshal Badoglio's observation post on a green African hillside, he watched Fascist bombers and blackshirts cut the Negus' forces to pieces. The Ethiopians' valor in the murderous battle of Amba Aradam made no immediate impression on his political consciousness. He came out of the campaign with an Italian War Cross, and no idea that he had witnessed a rehearsal for World War II. "The right or the wrong of it did not interest me greatly," he confesses.

But when he got to Spain, his first lesson began to sink in: Fascism was designed for export, and anybody who did not want to import it must fight it. Somewhere between Valencia, blitzed Barcelona and Madrid, his ivory tower crumbled, and Matthews stepped from its rubble to do the best reporting of his career. Because it was also optimistic reporting, he wound up feeling as sick at heart as the Spanish Republicans...

The greatest lesson was political. Looking back over the wreckage of Europe, midway in the "century of totalitarianism," Matthews sees "the democracies and the Communist power facing each other over the stricken field of Fascism. They need not settle their differences by war... But war, as we have learned to our sorrow, is not avoided by appeasement; it is avoided by possessing the strength to hold your own and by using that strength for political purposes."

If he had to choose between brands of totalitarianism Reporter Matthews - who has never been to Russia - would take Communism. His main hope: that he will never have to choose.

(9) Time Magazine (27th July, 1959)

New York Times man Herbert L. Matthews, veteran foreign correspondent and champion of causes, scored an enviable news beat in 1957, when he made his way into the mountain fastness of Cuba's Oriente province, became the first U.S. newsman to interview Rebel Leader Fidel Castro. Matthews reported not only that Castro was alive (the Batista government had been claiming him dead), but that he represented Cuba's future. Wrote Matthews: "He has strong ideas of liberty, democracy, social justice, the need to restore the constitution, to hold elections."

Last week, with Castro's ideas of liberty, democracy and social justice in serious question, with Cuba's constitution ignored at Castro's fancy, with elections not even in prospect, Herb Matthews was back in Cuba. He had been disturbed by growing U.S. criticism of the Castro regime. "The Cuba story was getting all confused in New York," he told a fellow reporter. "I thought I'd come down."

He found that nothing - or almost nothing - had changed since he first fell under Castro's spell. Said he: "The only difference I saw was that he's putting on weight around the middle." With other newsmen - including the Times's full time Cuba correspondent, Ruby Hart Phillips - reporting growing discontent with the Castro regime, growing concern about Communist influence, Matthews presented a far brighter picture. "This is not a Communist revolution in any sense of the word, and there are no Communists in positions of control." Matthews offered a remarkable proof: "Even the agrarian reform, Cubans point out with irony, is not at all what the Communists were suggesting, for it is far more radical and drastic than the Reds consider wise as a first step to the collectivization they, but not the Cubans, want." But as early as April 23, Times-woman Ruby Phillips, in a story run by the Times (over Matthews' strong objections), reported in detail on "a Communist pattern in the development of the revolutionary program." Again, in May, Ruby Phillips wrote: "Since the victory of the Castro revolution last January, the Communists and the 26th of July movement have been in close cooperation." Most newsmen agreed. "The unrelenting enemies Dr. Castro has made because of his agrarian reform and economic measures are few, have no mass backing and are unarmed," wrote Matthews. On the same subject, Colleague Phillips had reported: "Many people with modest savings, as well as the wealthy class, have invested in land and property . . . and they now see themselves stripped of their possessions. They are greatly disillusioned."

Where Matthews reserved the word "dictator" for Cuba's ousted President Fulgencio Batista, he sees Castro's regime as a benevolent sort of one-man rule. Wrote he: "Premier Castro is avoiding elections in Cuba for two reasons. He feels that his social revolution now has dynamism and vast popular consent, and he does not want to interrupt the process. Moreover, most observers would agree that Cubans today do not want elections."

In the early editions of the Times for the morning after Castro resigned last week, Matthews speculated that the move came not from troubles within Cuba but out of resentment of U.S. criticism: "One must suppose that he has foreign policy and U.S. opinion mostly in mind. The attacks on him in the U.S. have wounded and angered him." But when Castro himself said that his resignation stemmed from his feud with the President of his own choosing, Manuel Urrutia Lleo, and that a lot of the trouble arose because Urrutia had spoken unkindly of the Communists, the Times withdrew the Matthews analysis from its later editions.

(10) Earl E. T. Smith gave evidence to the Senate Committee on the Judiciary on 27th August, 1960.

F. W. Sourwine: Mr. Smith, when you were appointed Ambassador to Cuba, were you briefed on the job?

Earl E. Smith: Yes; I was.

F. W. Sourwine: Who gave you this briefing?

Earl E. Smith: I spent 6 weeks in Washington, approximately 4 days of each week, visiting various agencies and being briefed by the State, Department and those whom the State Department designated.

F. W. Sourwine: Any particular individual or individuals who, had a primary part in this briefing?

Earl E. Smith: The answer is, in the period of 6 weeks I was briefed by numbers of people in the usual course as every Ambassador is briefed.

F. W. Sourwine: Is it true, sir, that you were instructed to get a briefing on your new job as Ambassador to Cuba from Herbert Matthews of the New York Times?

Earl E. Smith: Yes; that is correct.

F. W. Sourwine: Who gave you these instructions?

Earl E. Smith: William Wieland, Director of the Caribbean Division and Mexico. At that time he was Director of the Caribbean Division, Central American Affairs.

F. W. Sourwine: Did you, sir, in fact see Matthews?

Earl E. Smith: Yes; I did.

F. W. Sourwine: And did he brief you on the Cuban situation?

Earl E. Smith: Yes; he did.

F. W. Sourwine: Could you give us the highlights of what he told you?...

Earl E. Smith: We talked for 2 1/2 hours on the Cuban situation, a complete review o£ his feelings regarding Cuba, Batista, Castro, the situation in Cuba, and what he thought would happen.

F. W. Sourwine: What did he think would happen?

Earl E. Smith: He did not believe that the Batista government could last, and that the fall of the Batista government would come relatively soon.

F. W. Sourwine: Specifically what did he say about Castro?

Earl E. Smith: In February 1957 Herbert L. Matthews wrote three articles on Fidel Castro, which appeared on the front page of the New York Times, in which he eulogized Fidel Castro and portrayed him as a political Robin Hood, and I would say that he repeated those views to me in our conversation....

F. W. Sourwine: What did Mr. Matthews tell you about Batista?

Earl E. Smith: Mr. Matthews had a very poor view of Batista, considered him a rightist ruthless dictator whom he believed to be corrupt. Mr. Matthews informed me that he had very knowledgeable views of Cuba and Latin American nations, and had seen the same things take place in Spain. He believed that it would be in the best interest of Cuba and the best interest of the world in general when Batista was removed from office.

F. W. Sourwine: It was true that Batista's government was corrupt, wasn't it?

Earl E. Smith: It is true that Batista's government was corrupt. Batista was the power behind the Government in Cuba off and on for 25 years. The year 1957 was the best economic year that Cuba had ever had.

However, the Batista regime was disintegrating from within. It was becoming more corrupt, and as a result, was losing strength. The Castro forces themselves never won a military victory. The best military victory they ever won was through capturing Cuban guardhouses and military skirmishes, but they never actually won a military victory.

The Batista government was overthrown because of the corruption, disintegration from within, and because of the United States and the various agencies of the United States who directly and indirectly aided the overthrow of the Batista government and brought into power Fidel Castro.

F. W. Sourwine: What were those, agencies, Mr. Smith?

Earl E. Smith: The US Government agencies - may I say something off the record?

(Discussion off the record.)

F. W. Sourwine: Mr. Smith, the pending question before you read your statement was: What agencies of the US Government had a hand in bringing pressure to overthrow the Batista government, and how did they do it?

Earl E. Smith: Well, the agencies, certain influential people, influential sources in the State Department, lower down echelons in the CIA. I would say representatives of the majority of the US Government agencies which have anything to do with the Embassy...

F. W. Sourwine: Mr. Smith, when you talked with Matthews to get the briefing before you went to Cuba, was he introduced to you as having any authority from the State Department or as being connected with the State Department in any way?

Earl E. Smith: Let me go back. You asked me a short while ago who arranged the meeting with Mr. Matthews.

F. W. Sourwine: And you said Mr. Wieland.

Earl E. Smith: I said Wilham Wieland, but Wilham Wieland also had to have the approval of Roy Rubottom, who was then Assistant Secretary of State for Latin American Affairs. Now, to go back to this question, as I understood it, you said - would you mind repeating that again?

F. W. Sourwine: I asked if, when you were, sent to Mr. Matthews for this briefing, he was introduced to you as having any official connection with the State Department or any authority from the Department?

Earl E. Smith: Oh, no. I knew who he was, and they obviously knew I knew who he was, but I believe, that they thought it would be a good idea for me to get the viewpoint of Herbert Matthews, and also I think that Herbert Matthews is the leading Latin American editorial writer for the New York Times. Obviously the State Department would like to have the support of the New York Times...

James Eastland: Mr. Smith, we have had hearings, a great many, in Miami, with prominent Cubans, and there is a thread that runs through the whole thing that people connected with some Government agency went to Cuba and called on the chiefs of the armed forces and told them that we would not recognize the government of the President-elect, and that we would not back him, and that because of that the chiefs of the armed forces told Batista to leave the country, and they set up a government in which they attempted to make a deal with Castro. That is accurate, isn't it, Tom?

Thomas Dodd: I would say so, yes...

James Eastland: Let me ask you this question. As a matter of fact, isn't it your judgment that the State Department of the United States is primarily responsible for bringing Castro to power in Cuba?

Earl E. Smith: No, sir, I can't say that the State Department in itself is primarily responsible. The State Department played a large part in bringing Castro to power. The press, other Government agencies, Members of Congress are responsible...

James Eastland: You had been warning the State Department that Castro was a Marxist?

Earl E. Smith: Yes, sir.

James Eastland: And that Batista's government was a friendly government. That is what had been your advice as to the State Department?

Earl E. Smith: Let me answer that this way, which will make it very clear. When I went to Cuba, I left here with the definite feeling according to my briefings which I had received, that the U.S. Government was too close to the Batista regime, and that we were being accused of intervening in the affairs of Cuba by trying to perpetuate the Batista dictatorship.

After I had been in Cuba for approximately 2 months, and had made a study of Fidel Castro and the revolutionaries, it was perfectly obvious to me as it would be to any other reasonable man that Castro was not the answer; that if Castro came to power, it would not be in the best interests of Cuba or in the best interests of the United States....

In my own Embassy there were certain ones of influence who were pro-26th of July, pro-Castro, and anti-Batista.

James Eastland: Who were they?

Earl E. Smith: Do I have to answer that question, Senator?

James Eastland: Yes, I think you have to. We are not going into it unnecessarily.

Earl E. Smith: I don't want to harm anybody. That is the reason I asked.

I would say the Chief of the Political Section, John Topping, and the Chief of the CIA Section. It was revealed that the No. 2 CIA rnan in the embassy had given unwarranted and undue encouragement to the revolutionaries. This came out in the trials of naval officers after the Cienfuegos revolution of September I957...

James Eastland: He (Batista) didn't have to leave. He had not been defeated by armed force.

Earl E. Smith: Let me put it to you this way: that there are a lot of reasons for Batista's moving out. Batista had been in control off and on for 25 years. His government was disintegrating, at the end due to corruption, due to the fact that he had been in power too long. Police brutality was getting worse.

On the other hand there were three forces that kept Batista in power. He had the support of the armed forces, he had support of the labor leaders. Cuba enjoyed a good economy.

Nineteen hundred and fifty-seven was one of the best years in the economic history of Cuba. The fact that the United States was no longer supporting Batista had a devastating psychological effect, upon the armed forces and upon the leaders of the labor movement. This went a long way toward bringing about his downfall.

On the other hand, our actions in the United States were responsible for the rise to power of Castro. Until certain portions of the American press began to write derogatory articles against the Batista government, the Castro revolution never got off first base.

Batista made the mistake of overemphasizing the importance of Prio, who was residing in Florida, and underestimating the importance of Castro. Prio was operating out of the United States, out of Florida, supplying the revolutionaries with arms, ammunition, bodies and money.

Batista told me that when Prio left Cuba, Prio and Alameia (Aleman) took $140 million out of Cuba. If we cut that estimate in half, they may have shared $70 million. It is believed that Prio spent a great many millions of dollars in the United States assisting the revolutionaries. This was done right from our shores....

F. W. Sourwine: Is there any doubt in your mind that the Cuban Government, under Castro, is a Communist government?

Earl E. Smith: Now?

F. W. Sourwine: Yes.

Earl E. Smith: I would go further. I believe it is becoming a satellite.

The logical thing for the Russians to do would be to move into Cuba which they had already done, and to take over, which they would do by a mutual security pact.

Then, when the United States objects, all they have to say is:

"We will get out of Cuba when you get out of Turkey."

Thomas Dodd: You are not suggesting-

Earl E. Smith: That is a speech I made in February.

Thomas Dodd: Yes, but you are not suggesting that the Communists will cease and desist from their activities in Cuba and Central and South America, or anywhere else, if we get out of these other places?

Earl E. Smith: Out of Turkey?

Thomas Dodd: Yes.

Earl E. Smith: It would mean a great deal to them if we got out of Turkey. I am no expert on Turkey.

Thomas Dodd: You do not have to be an expert on Turkey, but you ought to be a little bit of an expert on the Communists to know this would not follow at all.

Every time we have retreated from one place, they have moved into new areas.

Earl E. Smith: Senator, I did not say what they would do.

Thomas Dodd: I know, but...

Earl E. Smith: That they would move into Cuba to retaliate with us.