Peter Stolypin

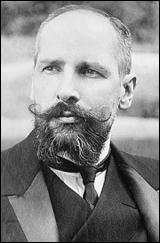

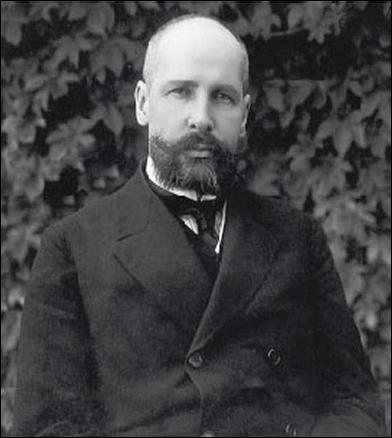

Peter Stolypin was born in Dresden on 14th April, 1862. The son of a large Russian landowner, Stolypin joined the Ministry of State Domains in 1885. Four years later he was appointed marshal of Kovno province. This was followed by the governorships of Grodno (1902-1903) and Saratov (1903-1906). Stolypin's draconian measures in suppressing the peasants in 1905 made him notorious. (1)

Chief Minister, Sergi Witte, advised Tsar Nicholas II to introduce political reforms following the 1905 Revolution. The Tsar reluctantly agreed and publish details of the proposed reforms that became known as the October Manifesto. This granted freedom of conscience, speech, meeting and association. He also promised that in future people would not be imprisoned without trial. Finally it announced that no law would become operative without the approval of the State Duma. It has been pointed out that "Witte sold the new policy with all the forcefulness at his command". He also appealed to the owners of the newspapers in Russia to "help me to calm opinions". (2)

The first meeting of the Duma took place in May 1906. A British journalist, Maurice Baring, described the members taking their seats on the first day: "Peasants in their long black coats, some of them wearing military medals... You see dignified old men in frock coats, aggressively democratic-looking men with long hair... members of the proletariat... dressed in the costume of two centuries ago... There is a Polish member who is dressed in light-blue tights, a short Eton jacket and Hessian boots... There are some socialists who wear no collars and there is, of course, every kind of headdress you can conceive." (3)

Several changes in the composition of the Duma had been changed since the publication of the October Manifesto. Nicholas II had also created a State Council, an upper chamber, of which he would nominate half its members. He also retained for himself the right to declare war, to control the Orthodox Church and to dissolve the Duma. The Tsar also had the power to appoint and dismiss ministers. At their first meeting, members of the Duma put forward a series of demands including the release of political prisoners, trade union rights and land reform. The Tsar rejected these proposals and dissolved the Duma in July, 1906. (4)

In April, 1906, Tsar Nicholas II forced Sergi Witte to resign and asked the more conservative Stolypin to take the post. At first he refused but the Tsar insisted: "Let us make the sign of the Cross over ourselves and let us ask the Lord to help us both in this difficult, perhaps historic moment." Stolypin told Bernard Pares that he was against the idea of a democratically elected Duma: "an assembly representing the majority of the population would never work". (5)

Stolypin attempted to provide a balance between the introduction of much needed land reforms and the suppression of the radicals. In October, 1906, Stolypin introduced legislation that enabled peasants to have more opportunity to acquire land. They also got more freedom in the selection of their representatives to the Zemstvo (local government councils). "By avoiding confrontation with peasant representatives in the Duma, he was able to secure the privileges attached to nobles in local government and reject the idea of confiscation." (6)

Peter Stolypin and the Duma

However, he also introduced new measures to repress disorder and terrorism. On 25 August 1906, three assassins wearing military uniforms, bombed a public reception Stolypin was holding at his home on Aptekarsky Island. Stolypin was only slightly injured, but 28 others were killed. Stolypin's 15-year-old daughter had both legs broken and his 3-year-old son also had injuries. The Tsar suggested that the Stolypin family moved into the Winter Palace for protection. (7)

Elections for the Second Duma took place in 1907. Peter Stolypin, used his powers to exclude large numbers from voting. This reduced the influence of the left but when the Second Duma convened in February, 1907, it still included a large number of reformers. After three months of heated debate, Nicholas II closed down the Duma on the 16th June, 1907. He blamed Lenin and his fellow-Bolsheviks for this action because of the revolutionary speeches that they had been making in exile. (8)

Members of the moderate Constitutional Democrat Party (Kadets) were especially angry about this decision. The leaders, including Prince Georgi Lvov and Pavel Milyukov, travelled to Vyborg, a Finnish resort town, in protest of the government. Milyukov drafted the Vyborg Manifesto. In the manifesto, Milyukov called for passive resistance, non-payment of taxes and draft avoidance. Stolypin took revenge on the rebels and "more than 100 leading Kadets were brought to trial and suspended from their part in the Vyborg Manifesto." (9)

Law and Order

Stolypin's repressive methods created a great deal of conflict. Lionel Kochan, the author of Russia in Revolution (1970), pointed out: "Between November 1905 and June 1906, from the ministry of the interior alone, 288 persons were killed and 383 wounded. Altogether, up to the end of October 1906, 3,611 government officials of all ranks, from governor-generals to village gendarmes, had been killed or wounded." (10) Stolypin told his friend, Bernard Pares, that "in no country is the public more anti-governmental than in Russia". (11)

The Russian government considered Germany to be the main threat to its territory. This was reinforced by Germany's decision to form the Triple Alliance. Under the terms of this military alliance, Germany, Austria-Hungary and Italy agreed to support each other if attacked by either France or Russia. Although Germany was ruled by the Tsar's cousin, Kaiser Wilhelm II, he accepted the views of his ministers and in 1907 agreed that Russia should joined Britain and France to form the Triple Entente.

Peter Stolypin instituted a new court system that made it easier for the arrest and conviction of political revolutionaries. In the first six months of their existence the courts passed 1,042 death sentences. It has been claimed that over 3,000 suspects were convicted and executed by these special courts between 1906 and 1909. As a result of this action the hangman's noose in Russia became known as "Stolypin's necktie". (12)

Peter Stolypin now made changes to the electoral law. This excluded national minorities and dramatically reduced the number of people who could vote in Poland, Siberia, the Caucasus and in Central Asia. The new electoral law also gave better representation to the nobility and gave greater power to the large landowners to the detriment of the peasants. Changes were also made to the voting in towns and now those owning their own homes elected over half the urban deputies.

In 1907 Stolypin introduced a new electoral law, by-passing the 1906 constitution, which assured a right-wing majority in the Duma. The Third Duma met on 14th November 1907. The former coalition of Socialist-Revolutionaries, Mensheviks, Bolsheviks, Octobrists and Constitutional Democrat Party, were now outnumbered by the reactionaries and the nationalists. Unlike the previous Dumas, this one ran its full-term of five years.

Assassination of Stolypin

The revolutionaries were now determined to assassinate Stolypin and there were several attempts on his life. "He wore a bullet-proof vest and surrounded himself with security men - but he seemed to expect nevertheless that he would eventually die violently." The first line of his will, written shortly after he had become Prime Minister, read: "Bury me where I am assassinated." (13)

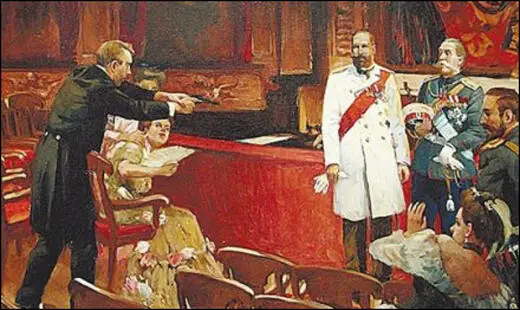

On 14th September, 1911, Peter Stolypin was shot by Dmitri Bogrov, a member of the Socialist Revolutionary Party, at the Kiev Opera House. Nicholas II was with him at the time: "During the second interval we had just left the box, as it was so hot, when we heard two sounds as if something had been dropped. I thought an opera glass might have fallen on somebody's head and ran back into the box to look. To the right I saw a group of officers and other people. They seemed to be dragging someone along. Women were shrieking and, directly in front of me in the stalls, Stolypin was standing. He slowly turned his face towards me and with his left hand made the sign of the Cross in the air. Only then did I notice he was very pale and that his right hand and uniform were bloodstained. He slowly sank into his chair and began to unbutton his tunic. People were trying to lynch the assassin. I am sorry to say the police rescued him from the crowd and took him to as isolated room for his first examination." (14)

Peter Stolypin died from his injuries on 18th September, 1911. He was the sixth Minister of the Interior in a row to be assassinated.

Primary Sources

(1) David Shub was a member of the Social Democratic Party when Peter Stolypin was in power.

Stolypin began to look for an excuse to dissolve the Duma and the Bolsheviks furnished him with one. Lenin insisted that the deputies use their parliamentary immunity to agitate for an armed uprising.

Years later it was discovered that these secret Bolshevik cells were infested with agents of the secret police. By keeping a sharp eye on the Social Democratic deputies, these stool pigeons were able to frame the deputies on the charges of inciting rebellion, thus giving Stolypin his excuse.

(2) Shornikova, was one of the secret agents planted by Stolypin and the Okhrana in the Social Democratic Party.

I met every member of the Central Committee then in St Petersburg, and all the members of the military organization; I knew all the secret meeting places and passwords of the revolutionary army cells throughout Russia. I kept the archives of the revolutionary organization in the Army; I was present at all the district meetings, propaganda rallies, and party conferences; I was always in the know. All the information I gathered was conscientiously reported to the Okhrana.

(3) Nicholas II was with Peter Stolypin when he was assassinated at the Kiev Opera House on 18th September, 1911.

During the second interval we had just left the box, as it was so hot, when we heard two sounds as if something had been dropped. I thought an opera glass might have fallen on somebody's head and ran back into the box to look. To the right I saw a group of officers and other people. They seemed to be dragging someone along. Women were shrieking and, directly in front of me in the stalls, Stolypin was standing. He slowly turned his face towards me and with his left hand made the sign of the Cross in the air. Only then did I notice he was very pale and that his right hand and uniform were bloodstained. He slowly sank into his chair and began to unbutton his tunic. People were trying to lynch the assassin. I am sorry to say the police rescued him from the crowd and took him to as isolated room for his first examination.

(4) General Alexei Polivanov, diary entry on the death of Peter Stolypin (19th September, 1911)

What a distressing feeling! Not to speak of the loss for Russia, I feel a personal bereavement. I was under the charm of this man. I delighted in him, I was proud to think that he was satisfied with my work. When I said goodbye to him on 6th September after the Cabinet meeting, as usual I tried to catch his eye. He stood by his chair, tall and upright, and his fine face looked healthy and tanned. It was on the 9th September that for the last time I heard his manly voice on the telephone.