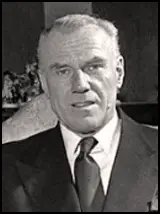

Victor Silvester

Victor Marlborough Silvester was born in Wembley, Middlesex on 25th February, 1900. The son of a vicar he was educated at Ardingly College.

The First World War began in 1914. As he later wrote in his autobiography: "The mood of the country was one of almost hysterical patriotism, and no excuses were accepted for any man of military age who was not in uniform. Rude remarks were made about them in the streets. Sometimes they were given white feathers."

Although he was only "fourteen and nine months" he ran away to join the British Army and by the age of fifteen he was fighting on the Western Front.

Silvester took part in the Battle of Arras and in 1917 he was a member of a firing squad that shot four British soldiers sentenced to death for desertion and cowardice. He later wrote: "The victim was brought out from a shed and led struggling to a chair to which he was then bound and a white handkerchief placed over his heart as our target area. He was said to have fled in the face of the enemy. Mortified by the sight of the poor wretch tugging at his bonds, twelve of us, on the order raised our rifles unsteadily. Some of the men, unable to face the ordeal, had got themselves drunk overnight. They could not have aimed straight if they tried, and, contrary to popular belief, all twelve rifles were loaded. The condemned man had also been plied with whisky during the night, but I remained sober through fear."

Victor Silvester's parents suspected he had joined the army and informed the authorities in 1914 but it was not until he was wounded in 1917 that he was discovered and brought home to England.

After the war Silvester went to Worcester College, Oxford. Later he studied music at Trinity College, London. Silvester was a talented dancer and in 1922 he won the first World Standard Ballroom Dancing Championship with Phyllis Clarke as his partner. Silvester was a founder member of the Ballroom Committee of the Imperial Society of Teachers of Dancing which codified the theory and practice of Ballroom Dance. In 1928 he published Modern Ballroom Dancing, which was an immediate bestseller.

In 1935 Silvester formed his own Ballroom Orchestra. His first record, You're Dancing on My Heart, was a great success. After the Second World War Silvester presented the BBC Television show Dancing Club for over 17 years.

Victor Marlborough Silvester died while on holiday in France on 14th August 1978.

Primary Sources

(1) Victor Silvester wrote about his experiences in the First World War in his autobiography Dancing Is My Life.

The mood of the country was one of almost hysterical patriotism, and no excuses were accepted for any man of military age who was not in uniform. Rude remarks were made about them in the streets. Sometimes they were given white feathers.

I was fourteen and nine months on the morning I played truant, and went up to the headquarters of the London Scottish at Buckingham Palace Gate. A sergeant in the recruiting office asked me what I wanted, and when I told him I had come to join the regiment he questioned me about my Scottish ancestry.

"My mother's father was a Scot," I said.

That seemed adequate, so he asked me my age.

"Eighteen and nine months."

"All right," the sergeant said. "Fill in this form and wait in the next room for the medical officer to look at you."

(2) Victor Silvester soon discovered that the war was very different to what he expected.

We went up into the front-line near Arras, through sodden and devastated countryside. As we were moving up to the our sector along the communication trenches, a shell burst ahead of me and one of my platoon dropped. He was the first man I ever saw killed. Both his legs were blown off and the whole of his face and body was peppered with shrapnel. The sight turned my stomach. I was sick and terrified, but even more frightened of showing it.

That night I had been asleep in a dugout about three hours when I woke up feeling something biting my hip. I put my hand down and my fingers closed on a big rat. It had nibbled through my haversack, my tunic and pleated kilt to get at my flesh. With a cry of horror I threw it from me.

(3) In an interview he gave just before his death in 1978, Victor Silvester described how in 1917 he was ordered to execute a man for desertion.

We marched to the quarry outside Staples at dawn. The victim was brought out from a shed and led struggling to a chair to which he was then bound and a white handkerchief placed over his heart as our target area. He was said to have fled in the face of the enemy.

Mortified by the sight of the poor wretch tugging at his bonds, twelve of us, on the order raised our rifles unsteadily. Some of the men, unable to face the ordeal, had got themselves drunk overnight. They could not have aimed straight if they tried, and, contrary to popular belief, all twelve rifles were loaded. The condemned man had also been plied with whisky during the night, but I remained sober through fear.

The tears were rolling down my cheeks as he went on attempting to free himself from the ropes attaching him to the chair. I aimed blindly and when the gunsmoke had cleared away we were further horrified to see that, although wounded, the intended victim was still alive. Still blindfolded, he was attempting to make a run for it still strapped to the chair. The blood was running freely from a chest wound. An officer in charge stepped forward to put the finishing touch with a revolver held to the poor man's temple. He had only once cried out and that was when he shouted the one word 'mother'. He could not have been much older than me. We were told later that he had in fact been suffering from shell-shock, a condition not recognised by the army at the time. Later I took part in four more such executions.