William Everard

William Everard was born in Reading in about 1602. According to Ariel Hessayon, his biographer: "It may be assumed that William Everard's family was poor for no one with the name Everard was assessed in the borough of Reading for a parliamentary subsidy between 1625 and 1641". At the age of fourteen he was apprenticed for eight years to Robert Miller of the Merchant Taylors' Company in London. (1)

During the English Civil War some radicals began writing and distributing pamphlets on soldiers' rights. Radicals such as John Lilburne, Richard Overton and John Wildman were unhappy with the way that the war was being fought. Whereas he hoped the conflict would lead to political change, this was not true of most of the Parliamentary leaders. "The generals themselves members of the titled nobility, were ardently seeking a compromise with the King. They wavered in their prosecution of the war because they feared that a shattering victory over the King would create an irreparable breach in the old order of things that would ultimately be fatal to their own position." (2)

William Everard and the Levellers

In 1647 people like Lilburne and Overton were described as Levellers. In September, 1647, William Walwyn, the leader of this group in London, organised a petition demanding reform. Their political programme included: voting rights for all adult males, annual elections, complete religious freedom, an end to the censorship of books and newspapers, the abolition of the monarchy and the House of Lords, trial by jury, an end to taxation of people earning less than £30 a year and a maximum interest rate of 6%. (3)

It seems that William Everard joined the Levellers and in May 1647 his name appears as an ensign on a petition voicing the grievances of the army under the command of General Thomas Fairfax. Everard was implicated in a plot to kill Charles I and was one of several men who in December 1647, while awaiting court martial, petitioned Fairfax against the injustice of their imprisonment. Some time afterwards Everard was cashiered from the army. (4)

Gerrard Winstanley

In October 1648 William Everard was arrested. It was reported that he held blasphemous opinions "as to deny God, and Christ, and Scriptures, and prayer". His arrest prompted Gerrard Winstanley to publish Truth Lifting up the Head above Scandals (1648), in which he asked who has the authority to restrain religious differences? He argued that Scripture, on which traditionally authority rested, was unsafe because there were no undisputed texts, translations, or interpretations. Winstanley concluded that authority should be based in the spirit. "All people carried the spirit, and thus their own authority, within them. The academics and clergy were following their own imaginations rather than the spirit and... must be seen as false prophets". (5)

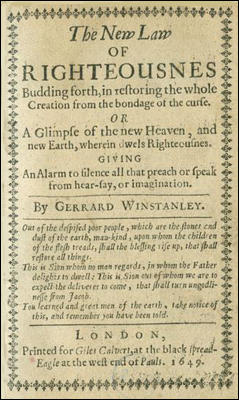

Winstanley gradually became more radical and he began arguing that all land belonged to the community rather than to separate individuals. In January, 1649, he published the The New Law of Righteousness. In the pamphlet he wrote: "In the beginning of time God made the earth. Not one word was spoken at the beginning that one branch of mankind should rule over another, but selfish imaginations did set up one man to teach and rule over another." (6)

Winstanley claimed that the scriptures threatened "misery to rich men" and that they "shall be turned out of all, and their riches given to a people that will bring forth better fruit, and such as they have oppressed shall inherit the land." He did not only blame the wealthy for this situation. As John Gurney has pointed out, Winstanley argued: "The poor should not just be seen as an object of pity, for the part they played in upholding the curse had also to be addressed. Private property, and the poverty, inequality and exploitation attendant upon it, was, like the corruption of religion, kept in being not only by the rich but also by those who worked for them." (7)

Winstanley claimed that God would punish the poor if they did not take action: "Therefore you dust of the earth, that are trod under foot, you poor people, that makes both scholars and rich men, your oppressors by your labours... If you labour the earth, and work for others that live at ease, and follows the ways of the flesh by your labours, eating the bread which you get by the sweat of your brows, not their own. Know this, that the hand of the Lord shall break out upon such hireling labourer, and you shall perish with the covetous rich man." (8)

On 6th March 1649 William Everard was bound by recognizance to appear at the Middlesex sessions of the peace. There he was charged with interrupting a church service at Staines-upon-Thames in "a threatening manner, shaking a hedging bill (a long-handled agricultural tool for cutting hedges) at the minister." (9)

The Diggers

On Sunday 1st April, 1649, Everard and Winstanley, and a small group of about 30 or 40 men and women started digging and sowing vegetables on the wasteland of St George's Hill in the parish of Walton. They were mainly labouring men and their families, and they confidently hoped that five thousand others would join them. (10)

The men sowed the ground with parsnips, carrots, and beans. They also stated that they "intended to plough up the ground and sow it with seed corn". (11) Research shows that new people joined the community over the next few months. Most of these were local inhabitants. These men became known as Diggers. (12)

John Gurney has argued that "Everard's flamboyant character and his preference for confrontation over presentation helped to ensure that in the early days of the digging he was more quickly noticed than the more self-effacing Winstanley, and many observers assumed that it was he, rather than Winstanley, who was the real leader of the Diggers". (13)

According to Peter Ackroyd, Everard proclaimed in a vision by God to "dig and plough the land" and that the Diggers believed in a form of "agrarian communism" and that that it was time for the English to free themselves from the the tyranny of Norman landlords and to make "the earth a common treasury for all." (14)

Winstanleyannounced his intentions in a manifesto entitled The True Levellers Standard Advanced (1649). It opened with the words: "In the beginning of time, the great Creator Reason, made the Earth to be a Common Treasury, to preserve Beasts, Birds, Fishes, and Man, the lord that was to govern this Creation; for Man had Domination given to him, over the Beasts, Birds, and Fishes; but not one word was spoken in the beginning, that one branch of mankind should rule over another." (15)

Winstanley argued for a society without money or wages: "The earth is to be planted and the fruits reaped and carried into barns and storehouses by the assistance of every family. And if any man or family want corn or other provision, they may go to the storehouses and fetch without money. If they want a horse to ride, go into the fields in summer, or to the common stables in winter, and receive one from the keepers, and when your journey is performed, bring him where you had him, without money." (16)

Digger groups also took over land in Kent (Cox Hill), Buckinghamshire (Iver) and Northamptonshire (Wellingborough). A. L. Morton has argued that Winstanley and his followers used the argument that William the Conqueror had "turned the English out of their birthrights; and compelled them for necessity to be servants to him and to his Norman soldiers." Winstanley responded to this situation by advocating what Morton describes as "primitive communism". (17)

Winstanley's writings suggested that he shared the view held by the Anabaptists that all institutions were by their nature corrupt: "nature tells us that if water stands long it corrupts; whereas running water keeps sweet and is fit for common use". To prevent power corrupting individuals he advocated that all officials should be elected every year. "When public officers remain long in place of judicature they will degenerate from the bounds of humility, honesty and tender care of brethren, in regard the heart of man is so subject to be overspread with the clouds of covetousness, pride, vain glory." (18)

Local landowners were very disturbed by these developments. According to one historian, John F. Harrison: "They were repeatedly attacked and beaten; their crops were uprooted, their tools destroyed, and their rough houses." (19) Oliver Cromwell also condemned the actions of the Diggers: "What is the purport of the levelling principle but to make the tenant as liberal a fortune as the landlord. I was by birth a gentleman. You must cut these people in pieces or they will cut you in pieces." (20)

On 16th April 1649, Henry Saunders, a yeoman of the parish, complained to the council of state about the growing number of Diggers, now "between 20 and 30". A report was sent to General Thomas Fairfax, the commander of the army, stating that "although the pretence of their being there by them avowed may seem very ridiculous, yet that conflux of people may be a beginning whence things of a greater and more dangerous consequence may grow to this disturbance of the peace and quiet of the Commonwealth." It suggested that Fairfax should send some troops to disperse the Diggers and prevent them from returning to St George's Hill. (21)

General Fairfax sent Captain John Gladman was sent to St George's Hill and found only four men digging. The camp had already been dealt with by local inhabitants: "They have digged in all about an acre of land, but it is trampled down by the country people, who would not suffer them to dig one day more." (22)

On 20th April, Gerrard Winstanley and William Everard, appeared before General Fairfax in London. Both men, because of their political beliefs, refused to remove their hats in the presence of the General. Everard told Fairfax that since the Norman Conquest, England had lived under a tyranny. He assured Fairfax that he and his fellows did not intend either to interfere with private property or to destroy enclosures, but that they were merely claiming the commons which were the rightful possession of the poor. The two men made it clear that they intended to cultivate the wastelands in common and to provide sustenance for the distressed." (23)

Gerrard Winstanley wrote to General Fairfax in June 1649 explaining his objectives: "And the truth is, experience shows us, that in this work of Community in the earth, and in the fruits of the earth, is seen plainly a pitched battle between the Lamb and the Dragon, between the Spirit of love, humility and righteousness... and the power of envy, pride, and unrighteousness ... the latter power striving to hold the Creation under slavery, and to lock and hide the glory thereof from man: the former power labouring to deliver Creation from slavery, to unfold the secrets of it to the sons of man, and so to manifest himself to be the great restorer of all things." (24)

Winstanley continued his experiment and on 1st June he published A Declaration from the Poor Oppressed People of England, that was signed by 44 people. It stated that while waiting for their first crop yields, they proposed to sell wood from the commons in order to buy food, ploughs, carts, and corn. No threat would be made to private property, but "the promises of reformation and liberation made from the solemn league and covenant through to the abolition of the monarchy and the House of Lords must be honoured". (25)

Evicted from St George's Hill

Instructions were given for the Diggers to be beaten up and for their houses, crops and tools to be destroyed. These tactics were successful and within a year all the Digger communities in England had been wiped out. A number of Diggers were indicted at the Surrey quarter sessions and five were imprisoned for just over a month in the White Lion prison in Southwark. (26)

Despite the hostility Winstanley's experiment continued and in January 1650 "having put my arm as far as my strength will go to advance righteousness: I have writ, I have acted, I have peace: and now I must wait to see the spirit do his own work in the hearts of others, and whether England shall be the first land, or some other, wherein truth shall sit down in triumph." (27)

On 19th April, 1650, a group of local landowners, including John Platt, Thomas Sutton, William Starr and William Davy, with several hired men, destroyed the Digger community in Cobham: "They set fire to six houses, and burned them down, and burned likewise some of the household stuff... not pitying the cries of many little children, and their frightened mothers.... they kicked a poor man's wife, so that she miscarried her child." (28) Over the next few months all the Digger settlements were destroyed. (29)

In the summer of 1650 Everard found work as a wheat thresher on the estate of Lady Eleanor Douglas at Pirton, Hertfordshire. However, in September 1650, he was arrested and charged with being suspected of being a "Sorcerer or Witch". It was claimed that he was mad and was sent to Bethlem Hospital. It is believed that he died at the hospital in March 1659. (30)

Primary Sources

(1) John Gurney, Gerrard Winstanley (2013)

Everard's flamboyant character and his preference for confrontation over presentation helped to ensure that in the early days of the digging he was more quickly noticed than the more self-effacing Winstanley, and many observers assumed that it was he, rather than Winstanley, who was the real leader of the Diggers.

(2) Ariel Hessayon, William Everard: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

On 6 March 1649 William Everard was bound by recognizance to appear at the Middlesex sessions of the peace. There he was charged with interrupting a church service at Staines in a threatening manner, shaking a hedging bill (a long-handled agricultural tool for cutting hedges) at the minister...

In April 1649 Everard attained even greater notoriety. Together with four others, all described as living at Cobham, he went to St George's Hill in Walton-on-Thames and began digging the earth. The men sowed the ground with parsnips, carrots, and beans, returning the next day in increased numbers. The following day they burned at least forty roods of heath.... By the end of the week between twenty and thirty people were reportedly labouring the entire day at digging... It was said that they intended to plough up the ground and sow it with seed corn.... Everard and Winstanley were the acknowledged leaders of these ‘new Levellers’ or ‘diggers’.