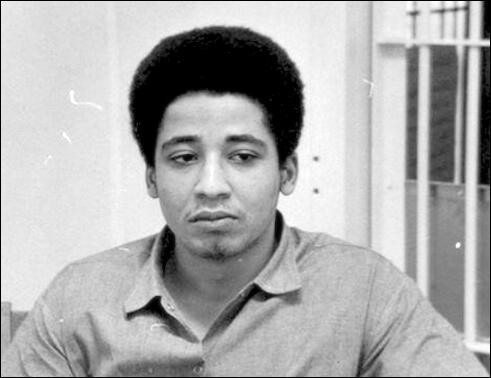

George Jackson

George Jackson was born in 1941. When he was eighteen Jackson was found guilty of stealing 70 dollars from a gas station and sentenced to "one year to life" in prison.

While in California's Soledad Prison Jackson and W. L. Nolen, established a chapter of the Black Panthers. On 13th January 1970, Nolen and two other black prisoners was killed by a prison guard. A few days later the Monterey County Grand Jury ruled that the guard had committed "justifiable homicide."

When a guard was later found murdered, Jackson and two other prisoners, John Cluchette and Fleeta Drumgo, were indicted for his murder. It was claimed that Jackson had sought revenge for the killing of his friend, W. L. Nolen.

On 7th August, 1970, George Jackson's seventeen year old brother, Jonathan, burst into a Marin County courtroom with a machine-gun and after taking Judge Harold Haley as a hostage, demanded that George Jackson, John Cluchette and Fleeta Drumgo, be released from prison. Jonathan Jackson was shot and killed while he was driving away from the courthouse.

Jackson published his book, Soledad Brother: Letters from Prison (1970). On 21st August, 1971, Jackson was gunned down in the prison yard at San Quentin. He was carrying a 9mm automatic pistol and officials argued he was trying to escape from prison. It was also claimed that the gun had been smuggled into the prison by Angela Davis. However, at her trial she was acquitted of all charges.

Primary Sources

(1) Angela Davis, wrote about visiting George Jackson's mother in her autobiography published in 1974.

When she began to talk about George, a throbbing silence came over the hall. "They took George away from us when he was only eighteen. That was ten years ago." In a voice trembling with emotion, she went on to describe the incident which had robbed him of the little freedom he possessed as a young boy struggling to become a man. He was in a car when its owner - a casual acquaintance of his - had taken seventy dollars from a service station. Mrs. Jackson insisted that he had been totally oblivious of his friend's designs. Nevertheless, thanks to an inept, insensitive public defender, thanks to a system which had long ago stacked the cards against young Black defendants like George, he was pronounced guilty of robbery. The matter of his sentencing was routinely handed over to the Youth Authority.

With angry astonishment I listened to Mrs. Jackson describe the sentence her son had received: One year to life in prison. One to life. And George had already done ten times the minimum. I was paralyzed by the thought of the absolute irreversibility of his last decade. And I was afraid to let my imagination trace out the formidable reality of those ten years in prison.

(2) George Jackson, Soledad Brother: Letters from Prison (1970)

Nothing has improved, nothing has changed in the weeks since your team was here. We're on the same course, the blacks are fast losing the last of their restraints. Growing numbers of blacks are openly passed over when paroles are considered. They have become aware that their only hope lies in resistance. They have learned that resistance is actually possible. The holds are beginning to slip away. Very few men imprisoned for economic crimes or even crimes of passion against the oppressor feel that they are really guilty. Most of today's black convicts have come to understand that they are the most abused victims of an unrighteous order. Up until now, the prospect of parole has kept us from confronting our captors with any real determination. But now with the living conditions deteriorating, and with the sure knowledge that we are slated for destruction, we have been transformed into an implacable army of liberation. The shift to the revolutionary anti-establishment position that Huey Newton, Eldridge Cleaver, and Bobby Seale projected as a solution to the problems of Amerika's black colonies has taken firm hold of these brothers' minds. They are now showing great interest in the thoughts of Mao Tse-tung, Nkrumah, Lenin, Marx, and the achievements of men like Che Guevara, Giap, and Uncle Ho.

We're something like 40 to 42 percent of the prison population. Perhaps more, since I'm relying on material published by the media. The leadership of the black prison population now definitely identifies with Huey, Bobby, Angela, Eldridge, and anti-fascism. The savage repression of blacks, which can be estimated by reading the obituary columns of the nation's dailies, Fred Hampton, etc., has not failed to register on the black inmates. The holds are being fast broken. Men who read Lenin, Fanon, and Che don't riot, "they mass," "they rage," they dig graves.

(3) Black Panther Intercommunal News Service (12th August 1978)

Fred Hampton once said, "You can kill a revolutionary but you can't kill the revolution." On August 21, 1971, the FBI, the state of California and other law enforcement agencies killed Black Panther Party Field Marshal George Lester Jackson at San Quentin Prison, but they failed to kill the revolutionary struggle of Black and poor prison inmates that George was instrumental in organizing throughout this country.

The recent prison rebellions at Folsom, California, Pontiac and Joliet, Illinois, and Reidsville, Georgia, are testaments to the life and untiring work of George Jackson to expose the inhumane conditions suffered by the millions of men and women warehoused in the prisons and jails of America. In their twisted and warped minds, the power structure - the real "criminal" - thought that by murdering George they could destroy the prison movement and the Black Panther Party.

Instead, the prison movement has continued to grow and spread throughout the country in the seven years since the cold- blooded murder of the BPP Field Marshal. Each week, the Black Panthers receive dozens of letters from prison inmates whose ideas strongly reflect the work and beliefs of George Jackson. Who can deny that the Attica Prison uprising of September 11, 1971, was partially caused by inmate anger over the killing of their beloved leader?

Former Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) agent provocateur Louis Tackwood testified in 1976 at the San Quentin 6 trial that his first assignment was to help plot George's murder. The state could not afford to allow the BPP Field Marshal to continue his highly successful prison organizing activities. Beyond the legendary reputation George had within the California penal system, his books were widely read by both prison inmates and those outside prison, books that challenged those opposed to the American penal system to take concrete action to overturn it.

(4) Huey P. Newton, The Murder of George Jackson (28th August 1971)

When I went to prison in 1967, I met George. Not physically, I met him through his ideas, his thoughts and words that I would get from him. He was at Soledad Prison at the time; I was at California Penal Colony.

George was a legendary figure all through the prison system, where he spent most of his life. You know a legendary figure is known to most people through the idea, or through the concept, or essentially through the spirit. So I met George through the spirit.

I say that the legendary figure is also a hero. He set a standard for prisoners, political prisoners, for people. He showed the love, the strength, the revolutionary fervor that's characteristic of any soldier for the people. So we know that spiritual things can only manifest themselves in some physical act, through a physical mechanism. I saw prisoners who knew about this legendary figure, act in such a way, putting his ideas to life; so therefore the spirit became a life.

And I would like to say today George's body has fallen, but his spirit goes on, because his ideas live. And we will see that these ideas stay alive, because they'll be manifested in our bodies and in those young Panther bodies, who are our children. So it's a true saying that there will be revolution from one generation to the next.

What kind of standard did George Jackson set? First, that he was a strong man, he was determined, full of love, strength, dedication to the people's cause, without fear. He lived the life that we must praise. It was a life, no matter how he was oppressed, no matter how wrongly he was done, he still kept the love for the people. And this is why he felt no pain in giving up his life for the people's cause.

The state sets the stage for the kind of contradiction or violence that occurs in the world, that occurs in the prisons. The ruling circle of the United States has terrorized the world. The state has the audacity to say they have the right to kill. They say they have a death penalty and it's legal. But I say by the laws of nature that no death penalty can be legal - it's only cold-blooded murder. It gives spur to all sorts of violence, because every man has a contract with himself, that he must keep himself alive at all costs.

They have the audacity to say that people should deliver a life to them without a struggle; but none of us can accept that. George Jackson had every right, every right to do everything possible to preserve his life and the life of his comrades, the life of the People.

George Jackson, even after his death, you see, is going on living in a very real way; because after all, the greatest thing that we have is the idea and our spirit, because it can be passed on. Not in the superstitious sense, but in the sense that when we say something or we live a certain way, then when this can be passed on to another person, then life goes on. And that person somehow lives, because the standard that he set and the standard that he lived by will go on living ...

Even with George's last statement - his last statement to me - at San Quentin that day, that terrible day, he left a standard for political prisoners; he left a standard for the prisoner society of racist, reactionary America; surely he left a standard for the liberation armies of the world. He showed us how to act.

(5) Jitu Sadiki, People's Tribune (27th August 1996)

I actually became aware of Comrade George a little over two years after his assassination. At the time, I was 17 years old and incarcerated in a segregated section of Los Angeles County Jail after a confrontation with police.

When I came back from court that day, they had moved everyone out in my section, separated by race. At that point, I was the only African in that section, but next to me was a Chicano brother who had a copy of Jackson's book, "Soledad Brother," and he gave it to me to read.

Years later, in September, 1976, when I was incarcerated in Soledad Prison, I began to find out more information about George and what had happened during that period and general knowledge of the prison movement. Conditions were extremely bad, prisoners really had no rights, the guards used their power to manipulate groups against one another, pretty much as they do now, but without the sophistication. The guards would routinely assault prisoners without repercussions.

Years later, when I ended up in "O" Wing, the same type of conditions were there, but just slightly more sophisticated. There would be open conflict between the races, and the guards openly facilitated that conflict.

In the summer of 1978, I was placed in solitary confinement. There were several incidents that happened that lengthened my stay and, in fact, there was a point where I believed I would never be released because of the commitment I had made to the struggle.

It was a quote from George that really helped me get through Soledad, Vacaville and San Quentin. He once said: "They will never count me among the broken men."

(6) Walter Rodney, George Jackson - Black Revolutionary (1971)

Once it is made known that George Jackson was a black revolutionary in the white man’s jails, at least one point is established, since we are familiar with the fact that a significant proportion of African nationalist leaders graduated from colonialist prisons, and right now the jails of South Africa hold captive some of the best of our brothers in that part of the continent. Furthermore, there is some considerable awareness that ever since the days of slavery the U.S.A. is nothing but a vast prison as far as African descendants are concerned. Within this prison, black life is cheap, so it should be no surprise that George Jackson was murdered by the San Quentin prison authorities who are responsible to America’s chief prison warder, Richard Nixon. What remains is to go beyond the generalities and to understand the most significant elements attaching to George Jackson’s life and death.

When he was killed in August this year, George Jackson was twenty nine years of age and had spent the last fifteen [correction: 11 years] behind bars – seven of these in special isolation. As he himself put it, he was from the "lumpen". He was not part of the regular producer force of workers and peasants. Being cut off from the system of production, lumpen elements in the past rarely understood the society which victimized them and were not to be counted upon to take organized revolutionary steps within capitalist society. Indeed, the very term "lumpen proletariat" was originally intended to convey the inferiority of this sector as compared with the authentic working class.

Yet George Jackson, like Malcolm X before him, educated himself painfully behind prison bars to the point where his clear vision of historical and contemporary reality and his ability to communicate his perspective frightened the U.S. power structure into physically liquidating him. Jackson’s survival for so many years in vicious jails, his self-education, and his publication of "Soledad Brother" were tremendous personal achievements, and in addition they offer on interesting insight into the revolutionary potential of the black mass in the USA, so many of whom have been reduced to the status of lumpen.