Laurie Lee

Laurie Lee, the son of Reginald Joseph Lee (1877–1947) and Annie Emily Lee (1879–1950) was born in Stroud, Gloucestershire, on 26th June, 1914.

His father worked as the manager of the local Co-operative grocery store before joining the Army Pay Corps at Greenwich during the First World War. He decided to live in London and never returned to the family home. Lee later remarked that "I, for one, scarcely missed him."

In June 1917 Annie Lee and her children moved from Stroud to the small village of Slad. He attended a local school and by the age of nine his teachers were commenting on his "strong imagination" and his ability to write "clever and amusing" stories. Unfortunately his schooling was interrupted by what his mother described as "long bouts of debilitating illness". This included attacks of pneumonia and bronchitis that left him with permanently weakened lungs.

At the age of sixteen Lee left school and joined Randall and Payne, chartered accountants, of Stroud, as an office junior. He was unhappy at work and in 1934 decided to walk to London. On his journey he made money by playing his violin in busking sessions. He settled in Putney where he found work as a builder's labourer.

Lee continued to write and his poems were published in The Gloucester Citizen and The Birmingham Post, and in October 1934 he won a poetry competition organized by a national newspaper, The Sunday Referee.

In July 1935 Lee decided to travel to Spain and while in the country visited Madrid, Córdoba, and Seville. While in Toledo he met Roy Campbell and Mary Campbell. They invited him back to their house for dinner, where he ended up staying for a week. He eventually found work as a violinist and odd job man at the Hotel Mediterraneo in Almuñécar.

During the early stages of the Spanish Civil War the area where he was living was bombed and Lee decided to return to England. Soon afterwards he met Lorna Wishart, the wife of Ernest Wishart, the owner of Lawrence and Wishart, on the beach at Gunwalloe. She stopped and asked him to play his violin for her. Valerie Grove has argued: "Rich, startlingly beautiful, the mother of two sons, she tempted and taunted him, showered him with gifts, was his Muse."

The couple began an affair but soon afterwards he decided to join the International Brigades. In his autobiography, A Moment of War, he explained what happened: "I told her my plans one evening as she sat twisting her hair with her fingers and gazing into my eves with her long cat look. She wasn't impressed. Others may need a war, she said; but you don't, you've got one here. She bared her beautiful small teeth and unsheathed her claws. Heroics like mine didn't mean a thing. If I wished to command her admiration by sacrificing myself to a cause she herself was ready to provide one."

On 5th December 1937 Lee crossed the Pyrenees and arrived at Albacete ten days later. He was then sent to the training centre at Tarazona. A report written at the end of the month concluded: "It seems clear that being, generally speaking, physically weak, he will not be of any use at the front. He agrees that the added excitement would be too much for him. On the other hand he seems a perfectly sincere comrade, who is very sympathetic to the Spanish government." Lee later commented: "I trained as a soldier, but I was mainly used in the International Brigade headquarters in Madrid during the siege, making short-wave broadcasts to Britain and America".

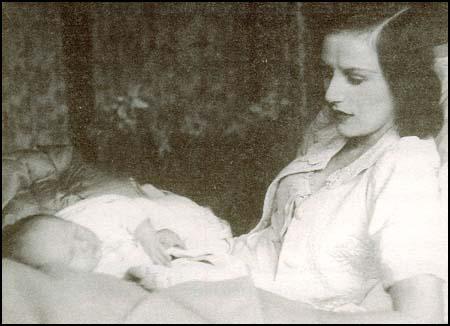

Laurie Lee left Spain on on 19th February, 1938. On his return to London he went to live with Lorna Wishart in Bloomsbury. According to Lee she was "rich and demandingly beautiful, extravagantly generous with her emotions but fanatically jealous". Their daughter, Yasmin, was born in February, 1939. However, three months later she decided to return to her husband. Ernest Wishart had made it a condition of taking her back that she stop seeing her lover.

However, the relationship continued. Valerie Grove has pointed out: "During the war he camped in a caravan near her husband’s Sussex estate; she arrived daily in her Bentley, bringing poetic inspiration and erotic fulfilment." Lee wrote at the time, "I cannot think why lovers ever leave their beds." Lee eventually left the caravan near Cissbury Ring and took a cottage in Bognor Regis. Lorna was intensely jealous of Lee. She wrote at the time: "I'm longing for you to grow old, each new wrinkle on your face is a joy to me - I want you to grow old and repulsive so that no one will want to look at you."

Laurie Lee's biographer, Valerie Grove, has pointed out in The Well-Loved Stranger (1999) that while the poet often said he loved women, "he never paid tribute to them as mentors; only as cosseting, embracing, accommodating creatures. He liked women, but in their place.'' As John Cunningham has argued: "Ernest Wishart was extremely forgiving. He seems to have accepted Lorna's bohemian streak, which ranged from her erotic encounters in an old farm-bound caravan that Lee rented in Sussex, to getting drunk with the literary set in London during the blackout. It might have been no more than damage limitation to keep the children of two fathers together, but, in agreeing to it, Wishart seems nobler than Lee, who didn't acknowledge his daughter until, as an adult, she sought him out."

In 1942 Lorna Wishart met the young artist, Lucian Freud, on holiday at Southwold. Lorna was ten years older than Freud but they soon became lovers. Freud's friend, John Craxton, commented: "Lorna was the most wonderful company, frightfully amusing and ravishingly good-looking: she could turn you to stone with a look. And she had deep qualities; she was not fluttery, she wasn't facile at all. She had a kind of mystery, a mystical inner quality. Any young man would have wanted her."

Laurie Lee continued to see Lorna. She wrote to Stephen Spender and Cyril Connolly about his talent and as a result some of his poems were published in Horizon. Lee's first volume of poetry, The Sun My Monument was published in 1944. Lorna also persuaded Connolly, the editor of the magazine, to use some of Freud's drawings.

According to her daughter Yasmin: "Lorna was a dream to any creative artist because she got them going. She was a natural muse, an inspiration. She was a symbol of their imagination, of their unconscious, she was nature herself: savage, wild, romantic and without guilt.'' Yasmin added: "She was amoral, really, but everyone forgave her because she was such a life-giver."

On the outbreak of the Second World War Lee attempted to join the British Army but because of his poor health he was rejected and instead he worked as a sound technician for the General Post Office film unit (1939–40), then as a scriptwriter with the Crown Film Unit (1941–3) and the Ministry of Information publications division (1944–6).

During this period he gained recognition as an important poet. His work was published in several literary magazines and he became friends with Stephen Spender, Cyril Connolly, Cecil Day-Lewis and Rosamond Lehmann. Lee published a second volume of poetry, The Bloom of Candles (1947) but over the next few years he concentrated on journalism and travel writing.

On 17 May 1950, Lee married eighteen-year-old Katherine Polge, the daughter of Jacob Epstein and Kathleen Garman and the niece of Lorna Wishart. The couple spent the winter of 1951–2 in Spain. This trip resulted in A Rose For Winter (1955). Despite having a lung removed this was a productive period and a third volume of new poetry, My Many Coated Man, was published in the same year.

In 1957 the Hogarth Press offered Lee £500 "to give up all other work and get on with" his proposed autobiography. Cider with Rosie was published two years later. It received excellent reviews and sold over six million copies. He followed this up with three more volumes of autobiography, As I Walked Out One Midsummer Morning (1969), I Can't Stay Long (1979), A Moment of War (1991).

Laurie Lee died of bowel cancer at his cottage in Slad on 13th May 1997 and was buried the lower graveyard at the local Holy Trinity Church.

Primary Sources

(1) Laurie Lee, A Moment of War (1991)

An official, bowed at his tiny desk, looked at me with a kind of puff-eyed indifference. Then he sniffed, asked me my name and my next of kin, and wrote down my answers in a child's exercise book. As he wrote he followed the motions of the pen with his tongue, breathing hard and sniffing rhythmically as he did so. Finally, he asked for my passport and threw it into a drawer, in which I saw a number of others of different colours.

"We'll take care of that for you," he said. "Would you like some prophylactics?"

Not knowing what these were, I nevertheless said yes, and he handed me a bagful which I stowed away in my pocket. Next he gave me a new hundred peseta note, a forage-cap with a tassel, and said, 'You are now in the Republican Army.' He considered me dimly for a moment, then suddenly shot to his feet, raised his fist and saluted.

(2) Laurie Lee's International Brigades file written on 23rd December 1937.

He did not come through the usual channels. He had tried to do so in January of this year when things were much stricter and he was turned down. He gives recommendations which seem to show that he is perfectly reliable. One of the men he knows is the present Commander of the British Battalion (Fred Copeman, strike organizer on the Putney building site, now attached to the staff of the 15th Brigade). We have not yet been able to check this, however. His reason for avoiding normal channels is that he did not want to be turned down and did not want anybody to go to the expense of sending him out, because he could not be sure of his physical fitness for the fighting out here. He paid his own fare out, and has enough cash to pay his own fare back if necessary.

He was in Spain from July 1935 to August 1936. He was then at Almuneca near Motril. He says that they were then shelled occasionally and this brought on the epileptic fits from which he suffers. Because of this he was evacuated by a British destroyer in August of 1936. His sympathies however were all with the Republic and he resolved to come out as soon as he had recovered. As stated above he tried to come in January, but was turned down.

After a year without any fits, he thought he was perfectly OK and decided to come definitely and here he is.

He had two epileptic fits in Figueras, which he attributes to the increased excitement of being in Spain and of his journey over the mountains.

He seems to be a fairly good violinist and artist. At present he is assisting in the cultural work at Tarazona.

It seems clear that being, generally speaking, physically weak, he will not be of any use at the front. He agrees that the added excitement would be too much for him. On the other hand he seems a perfectly sincere comrade, who is very sympathetic to the Spanish government.

(3) In his autobiography, A Moment of War (1991), Laurie Lee described how in Madrid soldiers searched for Nationalist supporters during bombing attacks.

It had happened before, when night-shelling was heavy and precise - someone, some 'Franco agent', would have been flashing a torch from a rooftop or an upper window, and then, when the bombardment was heaviest, would toss a few grenades down into the street to confuse the fire-trucks and rescue parties.

After two winters of siege, the inside war was still active, and not everyone, even in this poor bare tavern, as he talked and moved his eyes about, could be absolutely sure of the man who sat beside him.

'We caught one of them, anyway,' the younger soldier said fiercely. 'Running across the tiles with a cart lamp.'

'Could have been trying to save his skin,' said someone.

'Did you arrest him?'

'Hell, no. We just threw him off the roof. He'd done enough. His body's outside in a barrow.'

Someone drew back the shutters on the cold grey street. A boy sat on the shafts of a hand-barrow, smoking. Stretched out on sacks between the high wooden wheels lay the crumpled body of a thin, old man. It was smartly dressed, and the head which hung down from the tailboard still wore a white-haired look of distinction.

(4) Valerie Grove, The Times (9th June, 2004)

Lee was captivated, in the 1930s, by a woman named Lorna Wishart. Rich, startlingly beautiful, the mother of two sons, she tempted and taunted him, showered him with gifts, was his Muse, bore him a daughter. During the war he camped in a caravan near her husband’s Sussex estate; she arrived daily in her Bentley, bringing poetic inspiration and erotic fulfilment. And then, in 1943, she broke his heart. She had become infatuated with a 20-year-old Berlin-born artist, a boy wonder of the art world, with dark hair and pale, mesmeric eyes — Lucian Freud. She became his Muse, too: she was his first portrait subject, the first woman who meant anything to him. And when Wishart ditched him, he married Kitty, one of Wishart’s nieces, as his first wife — portrayed in his Girl With A White Dog, in Tate Britain. (Two years later, Lee did the same: he married Kathy, another of Wishart’s nieces.) This enthralling tale of a true femme fatale will be told later this summer in The Rare and the Beautiful, Cressida Connolly’s composite biography of Wishart and her eight equally amazing siblings.