Ralph de Diceto

Ralph de Diceto (Ralph of Diss) was probably born in Norfolk in about 1120. He seems to have moved to London and by 1136 he was reporting events that were taking place in the city. It has been suggested that he was related to Richard de Belmeis, the Bishop of London. (1)

Diceto received an education in Paris and in 1152 Diceto became archdeacon of St Paul's Cathedral and attended the coronation of Henry II on 19th December 1154. He seems to have toured France and wrote about what he found: "Aquitaine overflows with riches of many kinds, excelling other parts of the western world... Its lands are fertile, its vineyards productive and its forests team with wild life." (2)

On his return to England he began recording a chronological account of his times. According to his biographer: "He was a methodical and exact compiler of information of all kinds, and had probably been assembling material for years before he began to compose his chronicles." (3)

His collected work, Pictures of History, has been of great value to modern historians. As Alison Weir has pointed out: "He (Ralph de Diceto) was a conscientious researcher who took care to be accurate in his facts. His emphasis was on ecclesiastical history, but he used as sources a wealth of royal documents and contemporary letters, many of them he reproduced in his text." (4)

John Guy agrees: "The fullest, most sophisticated of the contemporary chroniclers of Henry II's reign is Ralph de Diceto... Based in London, he had good connections with the royal court, although he never held an official position there. A methodical compiler of facts illustrated by abridged versions of important letters and documents, he gives a vivid, commendably balanced narrative." (5)

Ralph de Diceto admired Henry II and argued: "King Henry sought to help those of his subjects who could least help themselves. When the king found that the sheriffs were using the public power in their own interests... he entrusted rights of justice to other loyal men of his realm." (6)

By 1164 he had acquired the livings of Aynho, Northamptonshire, and Finchingfield, Essex, and served them both by vicars. In that year he attended the Council of Northampton, and in 1166 was sent as a messenger by the English bishops to Archbishop Thomas Becket, who was then in exile. (7)

Ralph de Diceto discussed this matter with Becket's secretary, John of Salisbury in Rheims. As a result of these talks, Salisbury, Henry II and Louis VII of France met at Angers in April 1166. In a letter to Becket he complained that he wasted money and lost two horses on the journey and that it obtained nothing of value. (8)

Talks continued and on 7th January 1169, Becket and Henry met at Montmirail but they failed to reach an agreement. Pope Alexander III, finally ran out of patience and ordered Becket to agree a deal with Henry. (9) On 22nd July, 1170, Becket and Henry met at Fréteval and it was agreed that the archbishop should return to Canterbury and receive back all the possessions of his see. (10)

Archbishop Becket was murdered at Canterbury Cathedral on 29th December 1170. Edward Grim later reported: "The wicked knight (William de Tracy), fearing that the Archbishop would be rescued by the people in the nave... wounded this lamb who was sacrificed to God... cutting off the top of the head... Then he received a second blow on his head from Reginald FitzUrse but he stood firm. At the third blow he fell on his knees and elbows... Then the third knight (Richard Ie Breton) inflicted a terrible wound as he lay, by which the sword was broken against the pavement... the blood white with the brain and the brain red with blood, dyed the surface of the church. The fourth knight (Hugh de Morville) prevented any from interfering so the others might freely murder the Archbishop." (11) Although appalled by Becket's murder, he continued to respect and admire Henry II. (12)

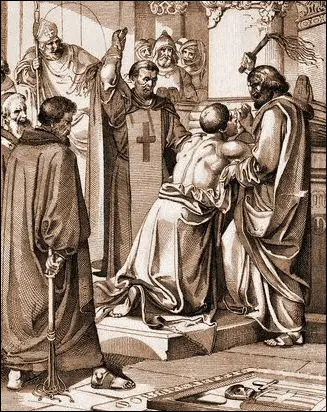

Henry II admitted that, although he never desired the killing of Becket, his words may have prompted the murderers. On 12th July, 1174, he agreed to do public penance. Ralph de Diceto reported: "When he (Henry II) reached Canterbury he leaped off his horse and, putting aside his royal dignity, he assumed the appearance of a pilgrim, a penitent, a supplicant, and on Friday 12 July, went to the cathedral. There, with streaming tears, groans and sighs, he made his way to the glorious martyr's tomb. Prostrating himself with his arms outstretched, he remained there a long time in prayer. He asked for absolution from the bishops then present, and subjected his flesh to harsh discipline from cuts with rods, receiving three or even five strokes from each of the monks in turn, of whom a large number had gathered." (13)

In 1180 he was elected dean of St Paul's Cathedral, and early in the following year conducted a detailed survey of the chapter's property. "He also enacted a statute of residence for the cathedral, in which he tried to strike a realistic balance between the needs of St Paul's for residentiary clergy, and the ever-increasing tendency for the canons to be pluralists and absentees." (14)

In 1187, along with Hubert Walter, he was a papal judge-delegate and on 3rd September 1189 he took part in the coronation of Richard the Lionheart. He reported in his chronicle: "The king (Richard I) had forbidden by public notice that any Jew or Jewess could come to his coronation... however, some leaders of the Jews arrived... the courtiers laid hands on the Jews and stripped them and flogged them and having inflicted blows, threw them out of the king's court. Some they killed, others they let go half dead... The people of London, following the courtier's example, began killing, robbing and burning the Jews. (15)

Ralph de Diceto died in about 1202.

Primary Sources

(1) Ralph de Diceto, Pictures of History (c. 1180)

King Henry sought to help those of his subjects who could least help themselves. When the king found that the sheriffs were using the public power in their own interests... he entrusted rights of justice to other loyal men of his realm.

(2) Ralph de Diceto, Chronicle (c. 1171)

When he (Henry II) reached Canterbury he leaped off his horse and, putting aside his royal dignity, he assumed the appearance of a pilgrim, a penitent, a supplicant, and on Friday 12 July, went to the cathedral. There, with streaming tears, groans and sighs, he made his way to the glorious martyr's tomb. Prostrating himself with his arms outstretched, he remained there a long time in prayer.

He asked for absolution from the bishops then present, and subjected his flesh to harsh discipline from cuts with rods, receiving three or even five strokes from each of the monks in turn, of whom a large number had gathered... He spent the rest of the day and also the whole of the following night in bitterness of soul, given over to prayer and sleeplessness, and continuing his fast for three days... There is no doubt that he had by now placated the martyr.

(3) Ralph de Diceto, Chronicle (c. 1189)

The king (Richard I) had forbidden by public notice that any Jew or Jewess could come to his coronation... however, some leaders of the Jews arrived... the courtiers laid hands on the Jews and stripped them and flogged them and having inflicted blows, threw them out of the king's court. Some they killed, others they let go half dead... The people of London, following the courtier's example, began killing, robbing and burning the Jews.

Student Activities

Henry II: An Assessment (Answer Commentary)

Thomas Becket and Henry II (Answer Commentary)

Why was Thomas Becket Murdered? (Answer Commentary)

Christine de Pizan: A Feminist Historian (Answer Commentary)

Wandering Minstrels in the Middle Ages (Answer Commentary)

The Growth of Female Literacy in the Middle Ages (Answer Commentary)

Women and Medieval Work (Answer Commentary)

The Medieval Village Economy (Answer Commentary)

Women and Medieval Farming (Answer Commentary)

Contemporary Accounts of the Black Death (Answer Commentary)

Disease in the 14th Century (Answer Commentary)

King Harold II and Stamford Bridge (Answer Commentary)

The Battle of Hastings (Answer Commentary)

William the Conqueror (Answer Commentary)

The Feudal System (Answer Commentary)

The Domesday Survey (Answer Commentary)

Illuminated Manuscripts in the Middle Ages (Answer Commentary)