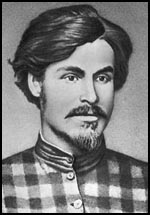

Stephan Khalturin

Stephan Khalturin, the son of a peasant, was born in Viatka (Kirov) in 1857. He became a carpenter and was employed in several factories in St. Petersburg. During this period he met Anna Yakimova, a future revolutionary.

In 1879 he organized the first real trade union in Russia, the Northern Workers' Union, which actually never attracted more than sixty members. Khalturin also became involved in revolutionary politics. He argued that Tsar Alexander II should be killed by a representative of the labouring class.

In November 1879 Khalturin managed to find work as a carpenter in the Winter Palace. According to Adam Bruno Ulam, the author of Prophets and Conspirators in Pre-Revolutionary Russia (1998): "There was, incomprehensible as it seems, no security check of workman employed at the palace. Stephan Khalturin, a joiner, long sought by the police as one of the organizers of the Northern Union of Russian workers, found no difficulty in applying for and getting a job there under a false name. Conditions at the palace, judging from his reports to revolutionary friends, epitomized those of Russia itself: the outward splendor of the emperor's residence concealed utter chaos in its management: people wandered in and out, and imperial servants resplendent in livery were paid as little as fifteen rubles a month and were compelled to resort to pilfering. The working crew were allowed to sleep in a cellar apartment directly under the dining suite."

Khalturin approached George Plekhanov about the possibility of using this opportunity to kill Tsar Alexander II. He rejected the idea but did put him in touch with the People's Will who were committed to a policy of assassination. It was agreed that Khalturin should try and kill the Tsar and each day he brought packets of dynamite, supplied by Anna Yakimova and Nikolai Kibalchich, into his room and concealed it in his bedding. Cathy Porter, the author of Fathers and Daughters: Russian Women in Revolution (1976), has argued: "His workmates regarded him as a clown and a simpleton and warned him against socialists, easily identifiable apparently for their wild eyes and provocative gestures. He worked patiently, familiarizing himself with the Tsar's every movement, and by mid-January Yakimova and Kibalchich had provided him with a hundred pounds of dynamite, which he hid under his bed."

On 17th February, 1880, Khalturin constructed a mine in the basement of the building under the dinning-room. The mine went off at half-past six at the time that the People's Will had calculated Alexander II would be having his dinner. However, his main guest, Prince Alexander of Battenburg, had arrived late and dinner was delayed and the dinning-room was empty. Alexander was unharmed but sixty-seven people were killed or badly wounded by the explosion.

Stephan Khalturin moved away from St. Petersburg and in March, 1882, he was captured while engaged in another assassination plot against the Governor-General of Odessa. He was executed a few days later.

Primary Sources

(1) Adam Bruno Ulam, Prophets and Conspirators in Pre-Revolutionary Russia (1998)

There was, incomprehensible as it seems, no security check of workman employed at the palace. Stephan Khalturin, a joiner, long sought by the police as one of the organizers of the Northern Union of Russian workers, found no difficulty in applying for and getting a job there under a false name. Conditions at the palace, judging from his reports to revolutionary friends, epitomized those of Russia itself: the outward splendor of the emperor's residence concealed utter chaos in its management: people wandered in and out, and imperial servants resplendent in livery were paid as little as fifteen rubles a month and were compelled to resort to pilfering. The working crew were allowed to sleep in a cellar apartment directly under the dining suite.

(2) Cathy Porter, Fathers and Daughters: Russian Women in Revolution (1976)

His workmates regarded Stephan Khalturin as a clown and a simpleton and warned him against socialists, easily identifiable apparently for their wild eyes and provocative gestures. He worked patiently, familiarizing himself with the Tsar's every movement, and by mid-January Yakimova and Kibalchich had provided him with a hundred pounds of dynamite, which he hid under his bed.

On 5 February he was ready to fire the charge that was to kill the Tsar in the Palace dining-room. In the event, the imperial dining plans were altered, and the blast merely damaged some empty rooms. It was hard to get any idea from him of what had actually happened, since when he arrived at the Podyacheskaya flat a little later he was raving and incoherent.