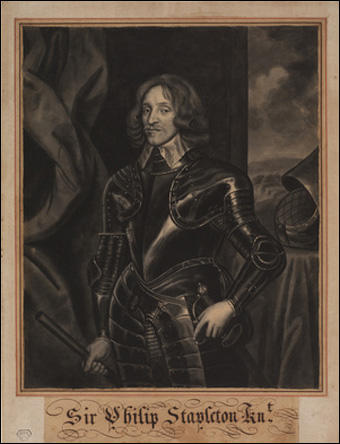

Sir Philip Stapleton

Peter Stapleton, the second son of Henry Stapleton and his wife, Mary Shepherd, the illegitimate daughter of Sir John Forster of Alnwick, was born in Wighill, in April 1603. He studied at Queens' College and after he left Cambridge University he was admitted to the Inner Temple in 1620. (1)

Stapleton inherited an estate worth £500 per year, and the Earl of Clarendon noted how he "according to the education of that country, spent his time in those delights which horses and dogs administer". (2)

Stapleton married Frances Gee, the widow of John Gee and the eldest daughter of Sir John Hotham, at Scorborough, on 8th October 1629. Shortly afterwards he purchased the estate at Warter Priory. He was knighted on 25th May 1630. His wife died in May 1636 and on 5th February 1638 he married again. His second wife was Barbara Lennard, daughter of Henry Lennard, twelfth Lord Dacre of Herstmonceux. (3)

House of Commons

Stapleton was elected MP for Hedon in the House of Commons and in June 1640 signed the petition against the forced billeting of royal soldiers in the county. He supported people like John Pym who suspected that King Charles I held pro-Catholic views and saw Parliament's role as safeguarding England against the influence of the Pope. He agreed with Pym when he said: "The high court of Parliament is the great eye of the kingdom, to find out offences and punish them". However, he believed that the king, who had married Henrietta Maria, a Catholic, was an obstacle to this process: "we are not secure enough at home in respect of the enemy at home which grows by the suspending of the laws at home". (4)

Pym was a believer in a vast Catholic plot. Some historians agree with Pym's theory: "Like all successful statesmen, Pym was up to a point an opportunist but he was not a cynic; and self-delusion seems the likeliest explanation of this and his supporters' obsession. That there was a real international Catholic campaign against Protestantism, a continuing determination to see heresy destroyed, is beyond dispute." (5)

Puritans and many other strongly committed Protestants were convinced that Archbishop William Laud and Thomas Wentworth, the Earl of Strafford, were the main figures behind this conspiracy. Wentworth was arrested in November, 1640, and sent to the Tower of London. Charged with treason, Wentworth's trial opened on 22nd March, 1641. The case could not be proved and so his enemies in the House of Commons, resorted to a Bill of Attainder. King Charles gave his consent to the Bill of Attainder and Thomas Wentworth, Earl of Strafford, was executed on 12th May 1641. (6)

On 20th August 1641 Stapleton was chosen, along with John Hampden, to visit the king in Scotland. Earl of Clarendon believed his activism was procured by Sir Hugh Cholmley and his former father-in-law, Sir John Hotham, "being much younger than they and governed by them". (7)

One member of parliament, Harbottle Grimstone, described Archbishop Laud as "the root and ground of all our miseries and calamities". Other bishops, including Matthew Wren of Ely, and John Williams of York, were also sent to the Tower. In December, 1641, Pym, introduced the Grand Remonstrance, that summarised all of Parliament's opposition to the king's foreign, financial, legal and religious policies. It also called for the expulsion of all bishops from the House of Lords. (8)

Stapleton fully supported this legislation. In the last week of December it was further agreed that parliament should meet at fixed times with or without the co-operation of the king. The Triennial Act was passed to compel parliaments to meet every three years. The Venetian ambassador to London reported that "if this innovation is introduced, it will hand over the reigns of government completely to Parliament, and nothing will be left to the king but mere show and a simulacrum of reality, stripped of credit and destitute of all authority". (9)

Sir Philip Stapleton and English Civil War

Charles I realised he could not allow the situation to continue. He decided to remove the leaders of the rebels in Parliament. On 4th January 1642, the king sent his soldiers to arrest John Pym, Arthur Haselrig, John Hampden, Denzil Holles and William Strode. The five men managed to escape before the soldiers arrived. Members of Parliament no longer felt safe from Charles and decided to form their own army. After failing to arrest the Five Members, Charles fled from London and formed a Royalist Army (Cavaliers) whereas his opponents established a Parliamentary Army (Roundheads). (10)

Attempts were made to negotiate and end to the conflict. On 25th July the king wrote to the vice-chancellor of Cambridge University inviting the colleges to assist him in his struggle. When they heard the news, the House of Commons sent Cromwell with 200 lightly armed countrymen to blocked the exit road from Cambridge. On 22nd August, 1642, the king "raised his standard" at Nottingham, and in doing so marked the beginning of the English Civil War. At a time when most Englishmen were dithering and waiting upon events, Oliver Cromwell decided to take action and captured Cambridge Castle and seized its store of weapons. (11)

Sir Philip Stapleton was commissioned as captain, under Robert Devereux, the Earl of Essex. The king marched around the Midlands enlisting support before marching on London. It is estimated he had about 14,000 followers by the time he encountered the Parliamentary Army at Edgehill on 22nd October, 1642. The Earl of Essex, only had 3,000 cavalry against the 4,000, serving the king. He therefore decided to wait until the rest of his troops, who were a day's march behind, arrived. (11a)

The battle began at 3 o'clock in the afternoon of the 23rd October. Prince Rupert and his Cavaliers made the first attack and easily defeated the left-wing of the Parliamentary forces. Henry Wilmot also had success on the right-wing but Stapleton and Cromwell were eventually able to repel the attack. Colonel Nathaniel Fiennes, later recalled that Cromwell "never stirred from his troops" and fought until the Cavaliers retreated. (12)

Prince Rupert's cavalrymen lacked discipline and continued to follow those who ran from the battlefield. John Byron and his regiment also joined the chase. The royalist calvary did not return to the battlefield until over an hour after the initial charge. By this time the horses were so tired they were unable to mount another attack against the Roundheads. The fighting ended at nightfall. Neither side had one a decisive advantage. (13) A pamphlet published at the time commented: "The field was covered with the dead, yet no one could tell to what party they belonged... Some on both sides did extremely well, and others did ill and deserved to be hanged." (14) According to Andrew J. Hopper, Stapleton's troopers played an important role in the victory. (15)

Stapleton also took part in the Battle of Newbury. King Charles I, with 8,000 foot soldiers and 6,000 cavalrymen, set up defensive positions to the west of Newbury. Prince Rupert was in command of the cavalry and Jacob Astley the infantry. Robert Devereux arrived with 10,000 foot soldiers and 4,000 cavalrymen. Although he arrived after the Royalists he managed to secure the best ground at Round Hill. An attack led by John Byron and his Cavaliers failed to capture the position from the Roundheads. (16) During the battle Stapleton had a brief confrontation with Prince Rupert in which he tried to shoot him with a pistol. (17)

Peace Party

Stapleton returned to the House of Commons where he became associated with the "peace party" led by Denzil Holles. Stapleton was willing to accept the return of the king to power on minimal terms, whereas Puritans like Oliver Cromwell demanded that Charles agree to firm limitations on his power before the army was disbanded. They also were committed to the idea that each congregation should be able to decide its own form of worship. (18)

The New Model Army, frustrated by this lack of agreement, took Charles prisoner, and he was taken to Hampton Court Palace. Cromwell visited the king and proposed a deal. He would be willing to restore him as King and the Church of England as the official Church, if Charles and the Anglicans would agree to grant religious toleration. Charles rejected Cromwell's proposals and instead entered into a secret agreement with forces in Scotland who wanted to impose Presbyterianism. (19)

The army secretary, John Rushworth, called Stapleton an incendiary and noted on 9th June 1647 that there was a danger that he would join the forces of the king. Stapleton was among the eleven MPs impeached by Sir Thomas Fairfax in the name of the army on 16th June. They were accused of incensing parliament against the army and endeavouring to provoke another civil war. Cromwell warned of the "sway Stapleton and Holles had heretofore in the kingdom". (20)

Sir Philip Stapleton fled with five of the other impeached members. On 14th August they boarded a ship on the Essex coast and landed at Calais on 17 August. Feverish and suffering from dysentery, Stapleton died on 18 August, 1647.

Primary Sources

(1) Andrew J. Hopper, Philip Stapleton : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

Stapleton was elected MP for Hedon in the Short Parliament and in June 1640 signed the petition of the Yorkshire gentry against the forced billeting of royal soldiers in the county. He was returned as MP for Boroughbridge in the Long Parliament and helped John Pym frame the charges against Strafford and abolish the council of the north. He was also appointed to a committee investigating the army plot in May 1641. He resided in London to attend parliamentary business and bought a house near St Ann Blackfriars. On 20 August 1641 he was chosen, along with John Hampden, to attend the king in Scotland. Clarendon believed his activism was procured by Sir Hugh Cholmley and his former father-in-law, Sir John Hotham, ‘being much younger than they and governed by them’ (Clarendon, Hist. rebellion, 1.393). Stapleton returned in time for the debates on the grand remonstrance during November 1641. In January 1642 he and Hotham were among the four members chosen by the House of Commons to deliver their answer to the king's demand for the arrest of the five members, and he was among the committee of twenty-five appointed to sit in the Guildhall during the adjournment of the house.

Early in May 1642 Stapleton was among the five parliamentary commissioners sent to report on the king's actions at York. He returned to London in June but Sir John Hotham, parliament's governor of Hull, requested his return and assistance to rally support in the county. After his appointment to the committee of safety on 4 July, Stapleton accompanied the earl of Holland northwards to present parliament's petition for peace to the king at Beverley on 16 July. He reported that the king had ‘noe foot’ and that Yorkshire's trained bands would only fight ‘faintly’ for him (Russell, 518). On his return he was commissioned as captain of the earl of Essex's life guard of gentlemen cuirassiers, and colonel of the lord-general's regiment of horse. He was given leave by the House of Commons to accompany Essex's army on 8 September. Stapleton's troopers helped save parliament's army by completing the rout of the king's infantry at the battle of Edgehill on 23 October 1642. Despite his appointments to the East Riding committees of sequestrations on 27 March 1643 and of levying money on 7 May 1643, he remained in the southern counties where he rallied the defeated parliamentarian cavalry at Chalgrove Field on 18 June 1643. During the first battle of Newbury he had a brief confrontation with Rupert in which he tried to shoot the prince with a pistol. After his appointment on 16 February 1644, he regularly attended the committee of both kingdoms, set up as a joint executive by parliament and the Scottish regime. In July 1644 Essex sent him to London to give a military report and he thereby avoided participation in the catastrophe that befell Essex's army in Cornwall.

Student Activities

Military Tactics in the Civil War (Answer Commentary)

References

(1) Andrew J. Hopper, Philip Stapleton : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(2) Earl of Clarendon, The History of the Rebellion (1667) page 393

(3) Andrew J. Hopper, Philip Stapleton : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(4) Diane Purkiss, The English Civil War: A People's History (2007) page 104

(5) Gerald E. Aylmer, Rebellion or Revolution: England from Civil War to Restoration (1986) page 30

(6) Barry Coward, The Stuart Age: England 1603-1714 (1980) pages 194-195

(7) Earl of Clarendon, The History of the Rebellion (1667) page 393

(8) Jasper Ridley, The Roundheads (1976) page 27

(9) Peter Ackroyd, The Civil War (2014) pages 204-205

(10) G. M. Trevelyan, English Social History (1942) page 256

(11) John Morrill, Oliver Cromwell : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(11a) Pauline Gregg, Oliver Cromwell (1988) pages 72-76

(12) Pauline Gregg, Oliver Cromwell (1988) page 77

(13) Roger Lockyer, Tudor and Stuart Britain (1985) page 272

(14) An Exact and True Relation of a Dangerous and Bloody Fight near Kineton (October, 1642)

(15) Andrew J. Hopper, Philip Stapleton : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(16) Peter Ackroyd, The Civil War (2014) pages 253-255

(17) Andrew J. Hopper, Philip Stapleton : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(18) Barry Coward, The Stuart Age: England 1603-1714 (1980) page 225

(19) Jasper Ridley, The Roundheads (1976) page 64

(20) Andrew J. Hopper, Philip Stapleton : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)