March of the Blanketeers

In March 1817 three working-class Radicals in Manchester, John Johnson, John Bagguley and Samuel Drummond decided to organise a protest march as a method of drawing attention to the problems of unemployed spinners and weavers in Lancashire. William Benbow, a Nonconformist preacher, became involved in organising the march.

The plan was for the men to take a petition to the Prince Regent. On the way to London the men hoped to hold meetings and to gain the support of other textile workers. It was believed that by the time they reached London there would be over 100,000 marchers willing to tell the royal family about the distress being caused by the growth of the factory system.

The leaders of the moderate reformers in Manchester, Archibald Prentice, John Shuttleworth and John Edward Taylor, were opposed to the proposed march. John Knight, Joseph Johnson, John Saxton and other Radical leaders in Manchester had doubts about the wisdom of this planned demonstration and decided not to encourage their supporters to take part in the march.

Samuel Bamford explained in his autobiography, Passage in the Life of a Radical (1843): "On the night of Sunday, the 9th of March, I was requested to attend a meeting in the house of one of my neighbours, where a number of friends wished to hear my opinion with reference to the Blanket Meeting. I went to them and spoke freely in condemnation of the measure. I endeavoured to show them that the authorities in Manchester were not likely to permit their leaving the town in a body, with blankets and petitions, as they proposed; that they could not subsist on the road; that the cold and wet would kill numbers of them, who were already enfeebled by hunger and other deprivations. That they need not expect to be welcome wherever they went, especially in the rotten boroughs. That many persons might join their ranks who were not reformers but enemies of reform, hired perhaps to bring them and their cause into disgrace; that if these persons began to plunder on the road, the punishment and disgrace would be visited on the whole body; that the would be denounced as robbers and rebels, and the military would be brought to cut them down or take them prisoners. Whether it was in consequence of what I said I cannot tell; but I was afterwards gratified on hearing that no person from Middleton went as a Blanketeer."

On the long march to London the organisers decided that each man should carry a blanket. As one observer pointed out: "The assemblage consisted almost entirely of operatives, four or five thousand in number. Many of the individuals were observed to have blankets, rugs, or large coats, rolled up and tied, knapsack like, on their backs; some carried bundles under their arms; some had papers, supposed to be petitions rolled up; and some had stout walking sticks."

As well as keeping them warm at night, the blanket indicated to the people who saw them on the march that they were weavers. As a result of the men carrying these blankets the demonstration became known as the March of the Blanketeers. Spies employed by the Manchester Magistrates sent in reports suggesting that the blanketeers might resort to violence on the march. The Magistrates therefore decided to make sure that the march to London did not take place.

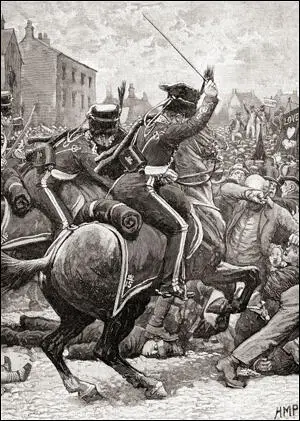

Johnson, Bagguley and Drummond planned to start the march off with a large meeting at St. Peter's Field in Manchester on 10th March, 1817. It is estimated that about 10,000 people attended, making it the largest meeting ever organised in Manchester. While the leaders of the meeting were speaking to the crowd, the King's Dragoon Guards were sent in by the Magistrates to arrest the leaders and to disperse the meeting. Twenty-nine men, including John Bagguley and Samuel Drummond, were taken into custody.

Archibald Prentice was in the crowd watching the attack: "A considerable detachment of the King's Dragoon Guards rode rapidly up to the hustings, which they surrounded, taking those who were upon them, twenty-nine in number, amongst whom were Bagguley and Drummond, into custody. When the field was cleared, a large body of soldiers and constables were despatched after those who had proceeded on the roads towards London."

A large number of the men were determined to march to London. The blanketeers were followed by the cavalry. One group was attacked a mile from the city centre. Others were apprehended at Macclesfield and Ashbourne. The worst violence took place at Stockport where several received sabre wounds and one man was shot dead. "Some hundreds were taken into custody, several received sabre wounds, and one industrious cottager, resident on the spot, was shot dead by the pistol of a dragoon, at whom a stone was thrown from the area where, with others, the poor man stood."

After the events of 10th March, 1817, the Magistrates decided that they needed their own military force that they could use during social unrest. The Magistrates therefore decided to form the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry Cavalry.

Primary Sources

(1) Samuel Bamford, Passage in the Life of a Radical (1843)

On the night of Sunday, the 9th of March, I was requested to attend a meeting in the house of one of my neighbours, where a number of friends wished to hear my opinion with reference to the Blanket Meeting. I went to them and spoke freely in condemnation of the measure. I endeavoured to show them that the authorities in Manchester were not likely to permit their leaving the town in a body, with blankets and petitions, as they proposed; that they could not subsist on the road; that the cold and wet would kill numbers of them, who were already enfeebled by hunger and other deprivations. That they need not expect to be welcome wherever they went, especially in the rotten boroughs. That many persons might join their ranks who were not reformers but enemies of reform, hired perhaps to bring them and their cause into disgrace; that if these persons began to plunder on the road, the punishment and disgrace would be visited on the whole body; that the would be denounced as robbers and rebels, and the military would be brought to cut them down or take them prisoners. Whether it was in consequence of what I said I cannot tell; but I was afterwards gratified on hearing that no person from Middleton went as a Blanketeer.

The meeting took place; but I not being there, my brief description must be taken as the account of others. The assemblage consisted almost entirely of operatives, four or five thousand in number. Many of the individuals were observed to have blankets, rugs, or large coats, rolled up and tied, knapsack like, on their backs; some carried bundles under their arms; some had papers, supposed to be petitions rolled up; and some had stout walking sticks. The magistrates came upon the field and read the Riot Act; the meeting was afterwards dispersed by the military and special constables, and twenty-nine persons were apprehended, amongst whom were two young men, named Bagguley and Drummond, who had recently come into notice as speakers, and who being in favour of extreme measures, were much listened to and applauded.

(2) In his book Personal Recollections of Manchester (1851) the author, Archibald Prentice described the Blanket Meeting at St. Peter's Field on 10th March, 1817.

Then came the 'Blanket Meeting' in St. Peter's Fields, Manchester, from which thousands of men were to march to London with their petition, each carrying a blanket or rug strapped to the shoulder. A considerable detachment of the King's Dragoon Guards rode rapidly up to the hustings, which they surrounded, taking those who were upon them, twenty-nine in number, amongst whom were Bagguley and Drummond, into custody.

When the field was cleared, a large body of soldiers and constables were despatched after those who had proceeded on the roads towards London. They came up with them on Lancashire Hill, near Stockport. Some hundreds were taken into custody, several received sabre wounds, and one industrious cottager, resident on the spot, was shot dead by the pistol of a dragoon, at whom a stone was thrown from the area where, with others, the poor man stood.