J. D. Tippit

J. D. Tippit (some sources claim he was christened Jefferson Davis) was born in Clarksville, Red River County, Texas, on September 18, 1924. During the Second World War Tippit served in the Seventeenth Airborne Division of the United States Army (July, 1944, to June, 1946).

Soon after leaving the army Tippit married Marie Frances Gasaway. The couple had three children. Over the next few years Tippit worked for Sears, Roebuck and Company (1948-1949) and as a farmer (1949-1950). The family eventually moved to Dallas and joined the Police Department in July, 1952. He was a successful officer and in 1956 he was cited for bravery for his role in disarming a criminal.

On 22nd November, 1963, President John F. Kennedy arrived in Dallas. It was decided that Kennedy and his party, including his wife, Jacqueline Kennedy, Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson, Governor John Connally and Senator Ralph Yarborough, would travel in a procession of cars through the business district of Dallas. A pilot car and several motorcycles rode ahead of the presidential limousine. As well as Kennedy the limousine included his wife, John Connally, his wife Nellie, Roy Kellerman, head of the Secret Service at the White House and the driver, William Greer. The next car carried eight Secret Service Agents. This was followed by a car containing Lyndon Johnson and Ralph Yarborough.

At about 12.30 p.m. the presidential limousine entered Elm Street. Soon afterwards shots rang out. John Kennedy was hit by bullets that hit him in the head and the left shoulder. Another bullet hit John Connally in the back. Ten seconds after the first shots had been fired the president's car accelerated off at high speed towards Parkland Memorial Hospital. Both men were carried into separate emergency rooms. Connally had wounds to his back, chest, wrist and thigh. Kennedy's injuries were far more serious. He had a massive wound to the head and at 1 p.m. he was declared dead.

Witnesses at the scene of the assassination claimed they had seen shots being fired from behind a wooden fence on the Grassy Knoll and from the Texas School Book Depository. The police investigated these claims and during a search of the Texas School Book Depository they discovered on the floor by one of the sixth floor windows, three empty cartridge cases. They also found a Mannlicher-Carcano rifle hidden beneath some boxes.

Oswald was seen in the Texas School Book Depository before (11.55 a.m.) and just after (12.31 p.m.) the shooting of John F. Kennedy. At 12.33 Oswald was seen leaving the building and by 1.00 p.m arrived at his lodgings. His landlady, Earlene Roberts, later reported that soon afterwards a police car drew up outside the house and sounded the horn twice and moved on. Roberts claimed that Oswald now left the building.

Tippit was one of the few officers in the Dallas Police Force not to be called to Dealey Plaza to help investigate the assassination. Instead, at 12.45 p.m. he was sent to the Oak Cliff section of Dallas.

At 1.16 p.m. Tippit approached a man, later identified as Lee Harvey Oswald, walking along East 10th Street. Domingo Benavides, later testified that after a short conversation, Oswald pulled out a hand gun and fired four shots at Tippit. However, Acquilla Clemons, who was sitting on a porch of a house close by, claimed that there were two men involved in the attack on Tippit. Another witness, Frank Wright, also claimed that Tippit was shot by two men.

Another witness, Helen Markham, also saw the killing. However, she described the killer as being short and somewhat on the heavy side, with slightly bushy hair." Later, Markham identified Oswald in a police lineup, but this was after she had seen his photograph on television.

Warren Reynolds did not see the shooting but saw the gunman running from the scene of the crime. He claimed that the man was not Oswald. After he survived an attempt to kill him, he changed his mind and identified Oswald as the man he had seen.

J. D. Tippit was buried in the memorial plot at Laurel Land Memorial Park, Dallas.

Primary Sources

(1) Joachim Joesten, How Kennedy Was Killed (1968)

When Chief Justice Warren and other members of the Commission on June 7, 1964, interviewed Ruby at the Dallas County jail. General Counsel Rankin told Ruby:

There was a story that you were sitting in your Carousel Club with Mr. (Bernard) Weissman, Officer Tippit, and another man who has been called a rich oil man, at one time shortly before the assassination. Can you tell us anything about that?'

To which Ruby replied with a counter-question: 'Who was the rich oil man?'

After that, unbelievably, the subject was dropped. Apparently, Messrs. Warren and Rankin felt they were getting too warm. Ruby's reaction indicated that he was ready to talk since he had nothing to lose. But the Commission members

weren't looking for the truth. They shied away from it, as from the plague. And so the topic was quickly shifted. Ruby

never got a second chance to answer 'yes' or 'no' to the vitally important question of whether such a meeting was held. Yet his surprise reaction, which so put off Messrs. Warren and Rankin that they quickly changed the subject, indicates that the story of that meeting is true...

Tippit, I am satisfied, was up to his neck in the conspiracy to kill President Kennedy. A Bircher, a marksman and a member of the police force which almost openly connived at the ambush in Dealey Plaza, he was most probably one of the actual snipers - and was quickly silenced for that very reason. And the description which Howard Brennan has given of the Man in the Window makes it a near-certainty, in my opinion, that Officer J. D. Tippit impersonated Lee Harvey Oswald at the deadliest part of the frame-up.

(2) Henry Hurt, Reasonable Doubt (1986)

It was just then, a minute or so past one o'clock, that Mrs. Roberts heard an automobile horn honk twice. The sound came from the street in front of the house, which was located at 1026 North Beckley Street in the Oak Cliff section of Dallas. Mrs. Roberts, who was the housekeeper at the rooming house, looked out the window and saw a Dallas Police Department patrol car stopped on the street in front.

Two uniformed officers were seated in it. Mrs. Roberts tried for a moment to make out the number marked on the car to see if it was familiar. This was her usual manner of recognizing the patrol car driven by police officers for whose wives she occasionally did housework. But it was not that car. Mrs. Roberts returned her attention to the television set.

Shortly afterward, the man known to her as O. H. Lee (Lee Harvey Oswald) came bustling out of the door to his room, zipping up a light jacket. He went out of the house, and Mrs. Roberts saw him walk toward the bus stop nearby. When Mrs. Roberts last glanced out the window, she could see Lee waiting at the bus stop, which served northbound bus routes. It was several minutes past 1:00 p.m...

It is intriguing, to say the least, that Oswald's departure from the rooming house occurred only moments after the strange appearance and horn-blowing of the patrol car from the Dallas Police Department. Exhaustive investigations have virtually established that the only police car officially in the vicinity was that of Officer J. D. Tippit. Less than fifteen minutes after this incident. Officer Tippit was savagely murdered and left dead in the street about a mile from Oswald's rooming house.

(3) Anthony Summers, The Kennedy Conspiracy (1980)

The star witness to the shooting was Mrs. Helen Markham, a Dallas waitress. She was supposedly the only person to see the shooting in its entirety. The official version accepted her as "reliable" and credited her with watching the initial confrontation between Tippit and his murderer peeping fearfully through her fingers as the murderer loped away and thus being able to identify Oswald at a police lineup. Yet this "reliable" witness made more nonsensical statements than can reasonably be catalogued here. She said she talked to Tippit and he understood her until he was loaded into an ambulance. All the medical evidence, and other witnesses, say Tippit died instantly from the head wound. A witness who also saw the shooting - from his pickup truck - and then got out to help the policeman, put it graphically: "He was lying there and he had - looked like a big clot of blood coming out of his head, and his eyes were sunk back in his head.... The policeman, I believe, was dead when he hit the ground." Mrs. Markham said it was twenty minutes before others gathered at the scene of the crime. That is clearly nonsense. Within minutes men were in Tippit's car calling for help on the police radio, and a small crowd was there when the ambulance arrived three minutes later, at 1:10 p.m. Mrs. Markham is credited with recognizing Oswald within three hours at the police station. It turns out that she was so hysterical at the police station that only after ammonia was administered could she go into the lineup room. When she appeared before the Commission Mrs. Markham repeatedly said she had been unable to recognize anyone at the lineup and changed her tune only after pressure from counsel. The star witness in the Tippit shooting was best summed up by Joseph Ball senior counsel to the Warren Commission itself. In 1964 he referred in a public debate to her testimony as being "full of mistakes" and to Mrs Markham as an "utter screwball." He dismissed her as "utterly unreliable," the exact opposite of the Report's verdict.

(4) Michael Kurtz, Crime of the Century: The Kennedy Assassination From a Historians Perspective (1982)

Helen Markham stated Oswald approached Tippit from the west, while another witness and the commission claimed he came from the east. She said she saw Oswald lean into an open window of the car; two witnesses and a photograph confirm that all windows were closed. She stated that Tippit tried to speak to her; all other witnesses, the commission, and the coroner found that he died instantly. She stated that she was alone with Tippit for twenty minutes; all other witnesses state that a large crowd gathered immediately. It is quite obvious that had Oswald been represented by a good defense attorney, Mrs. Markham would have had a few discrepancies to account for.

In the commission's account, J.D. Tippit, who was a "fine, dedicated officer," was driving his patrol car when he saw a man who fit the general description of the suspect wanted in the murder of President Kennedy. This "fine, dedicated officer," who had the chance to make the arrest of a lifetime, did not try to arrest this dangerous suspect, nor did he draw his gun (according to the wanted description broadcast over the police radio, the suspect was carrying a 30.06 rifle). Instead, he called the man over to his car and began having a casual conversation.

(5) David Welsh, Ramparts (November, 1966)

The Tippit killing was never conclusively "solved" by the Warren Commission. The gross faults in its chain of evidence pointing to Oswald as the lone cop-killer have been exposed in several recent books; we won't go into it here. Certainly, the Commission did not adequately investigate Tippit's movements prior to his death, or the curious presence near the scene of off-duty Patrolman Olsen, a close associate of Jack Ruby's.

On Bill Turner's last whirlwind trip to Dallas - acting on a tip from "sleuth" David Lifton - he uncovered five witnesses to Tippit's whereabouts in the last minutes of his life. There is no indication that the Commission or any police agency was even aware of them. Photographer Al Volkland and his wife Lou, both of whom knew Tippit, said that 15 or 20 minutes after the assassination they saw him at a gas station and waved to him. They observed Tippit sitting in his police car at a Gloco gas station in Oak Cliff, watching the cars coming over the Houston Street viaduct from downtown Dallas. Three employees of the Gloco station, Tom Mullins, Emmett Hollinshead and J.B. "Shorty" Lewis, all of whom knew Tippit, confirmed the Volklands' story. They said Tippit stayed at the station for "about 10 minutes, somewhere between 12:45 and 1:00, then he went tearing off down Lancaster at high speed" on a bee-line toward Jack Ruby's apartment and in the direciton of where he was killed a few minutes later.

What could Tippit have heard or seen to cause him to leave his observation post at the Gloco station and roar up the street? Police radio logs show no instructions to move. We know that cabdriver Whaley said he drove Oswald across the Houston Street viaduct (past the Gloco station at the same time Tippit was reported there) to a spot near the rooming house. Is it possible that Tippit spotted Oswald in the cab, recognized him, and for some reason took off to intercept him? If we recall that while Oswald was in the rooming house, Earlene Roberts observed a police car pull up in front and honk the horn, and the police statement that all cars in the area were accounted for - except Tippit's - then it is possible indeed. Earlene, who was blind in one eye and whose sight was failing in the other, said she thought the number on the car was 107; Tippit's car number was 10. Earlene said she saw two policemen in the car; all patrol cars in the area that day were one-man cars and Earlene, with her poor vision, may have mistaken Tippit's uniform jacket, hanging on a coat-hanger in his car, for another cop. The Commission should at least have investigated that possibility.

It is scandalous that three years after the event we should be reduced to this sort of speculation; that Turner, in one quick trip to Dallas, could learn more about Tippit's movements before his death than the combined investigative resources of the police, FBI, and Warren Commission.

(6) Helen Markham interviewed by William Ball for the Warren Commission (26th March, 1964)

William Ball: What did you notice then?

Helen Markham: Well, I noticed a police car coming.

William Ball: Where was the police car when you first saw it?

Helen Markham: He was driving real slow, almost up to this man, well, say this man, and he kept, this man kept walking, you know, and the police car going real slow now, real slow, and they just kept coming into the curb, and finally they got way up there a little ways up, well, it stopped.

William Ball: The police car stopped?

Helen Markham: Yes, sir.

William Ball: What about the man? Was he still walking?

Helen Markham: The man stopped.

William Ball: Then what did you see the man do?

Helen Markham: I saw the man come over to the car very slow, leaned and put his arms just like this, he leaned over in this window and looked in this window.

William Ball: He put his arms on the window ledge?

Helen Markham: The window was down.

William Ball: It was?

Helen Markham: Yes, sir.

William Ball: Put his arms on the window ledge?

Helen Markham: On the ledge of the window.

William Ball: And the policeman was sitting where?

Helen Markham: On the driver's side.

William Ball: He was sitting behind the wheel?

Helen Markham: Yes, sir.

William Ball: Was he alone in the car?

Helen Markham: Yes.

William Ball: Then what happened?

Helen Markham: Well, I didn't think nothing about it; you know, the police are nice and friendly, and I thought friendly conversation. Well, I looked, and there were cars coming, so I had to wait. Well, in a few minutes this man made--

William Ball: What did you see the policeman do?

Helen Markham: See the policeman? Well, this man, like I told you, put his arms up, leaned over, he just a minute, and he drew back and he stepped back about two steps. Mr. Tippit..

William Ball: The policeman?

Helen Markham: The policeman calmly opened the car door, very slowly, wasn't angry or nothing, he calmly crawled out of this car, and I still just thought a friendly conversation, maybe disturbance in the house, I did not know; well, just as the policeman got

William Ball: Which way did he walk?

Helen Markham: Towards the front of the car. And just as he had gotten even with the wheel on the driver's side...

William Ball: You mean the left front wheel?

Helen Markham: Yes; this man shot the policeman.

William Ball: You heard the shots, did you?

Helen Markham: Yes, sir.

William Ball: How many shots did you hear?

Helen Markham: Three.

William Ball: What did you see the policeman do?

Helen Markham: He fell to the ground, and his cap went a little ways out on the street.

William Ball: What did the man do?

Helen Markham: The man, he just walked calmly, fooling with his gun.

William Ball: Toward what direction did he walk?

Helen Markham: Come back towards me, turned around, and went back.

William Ball: Toward Patton?

Helen Markham: Yes, sir; towards Patton. He didn't run. It just didn't scare him to death. He didn't run. When he saw me he looked at me, stared at me. I put my hands over my face like this, closed my eyes. I gradually opened my fingers like this, and I opened my eyes, and when I did he started off in kind of a little trot.

William Ball: Did anybody tell you that the man you were looking for would be in a certain position in the lineup, or anything like that?

Helen Markham: No, sir.

William Ball: Now when you went into the room you looked these people over, these four men?

Helen Markham: Yes, sir.

William Ball: Did you recognize anyone in the lineup?

Helen Markham: No, sir.

William Ball: You did not? Did you see anybody - I have asked you that question before did you recognize anybody from their face?

Helen Markham: From their face, no.

William Ball: Did you identify anybody in these four people?

Helen Markham: I didn't know nobody.

William Ball: I know you didn't know anybody, but did anybody in that lineup look like anybody you had seen before?

Helen Markham: No. I had never seen none of them, none of these men.

William Ball: No one of the four?

Helen Markham: No one of them.

William Ball: No one of all four?

Helen Markham: No, sir.

William Ball: Was there a number two man in there?

Helen Markham: Number two is the one I picked.

William Ball: Well, I thought you just told me that you hadn't...

Helen Markham: I thought you wanted me to describe their clothing.

William Ball: No. I wanted to know if that day when you were in there if you saw anyone in there...

Helen Markham: Number two.

William Ball: What did you say when you saw number two?

Helen Markham: Well, let me tell you. I said the second man, and they kept asking me which one, which one. I said, number two. When I said number two, I just got weak.

William Ball: What about number two, what did you mean when you said number two?

Helen Markham: Number two was the man I saw shoot the policeman.

William Ball: You recognized him from his appearance?

Helen Markham: I asked - I looked at him. When I saw this man I wasn't sure, but I had cold chills just run all over me.

William Ball: When you saw him?

Helen Markham: When I saw the man. But I wasn't sure, so, you see, I told them I wanted to be sure, and looked, at his face is what I was looking at, mostly is what I looked at, on account of his eyes, the way he looked at me. So I asked them if they would turn him sideways. They did, and then they turned him back around, and I said the second, and they said, which one, and I said number two. So when I said that, well, I just kind of fell over. Everybody in there, you know, was beginning to talk, and I don't know, just...

William Ball: Did you recognize him from his clothing?

Helen Markham: He had on a light short jacket, dark trousers. I looked at his clothing, but I looked at his face, too.

William Ball: Did he have the same clothing on that the man had that you saw shoot the officer?

Helen Markham: He had, these dark trousers on.

William Ball: Did he have a jacket or a shirt? The man that you saw shoot Officer Tippit and run away, did you notice if he had a jacket on?

Helen Markham: He had a jacket on when he done it.

William Ball: What kind of a jacket, what general color of jacket?

Helen Markham: It was a short jacket open in the front, kind of a grayish tan.

William Ball: Did you tell the police that?

Helen Markham: Yes, I did.

William Ball: Did any man in the lineup have a jacket on?

Helen Markham: I can't remember that.

William Ball: Did this number two man that you mentioned to the police have any jacket on when he was in the lineup?

Helen Markham: No, sir.

William Ball: What did he have on?

Helen Markham: He had on a light shirt and dark trousers.

William Ball: Did you recognize the man from his clothing or from his face?

Helen Markham: Mostly from his face.

William Ball: Were you sure it was the same man you had seen before?

Helen Markham: I am sure.

(7) Robert J. Groden, The Search for Lee Harvey Oswald (1995)

Warren Reynolds was also one of the people to see a man fleeing the scene of the murder. Reynolds is on the South side of Jefferson Boulevard east of Patton Avenue in a used car lot. Initially, Reynolds stated that the man he saw was not Oswald. On January 23, 1964, Reynolds was shot in the head. A man named Darrell Garner was arrested for the shooting, but Betty Mooney MacDonald, who had worked for Jack Ruby gave Garner an alibi. MacDonald was then arrested for fighting with her roommate; the roommate was not arrested. MacDonald was found hanged in her jail cell. Reynolds, miraculously recovering from the gunshot wound, then changed his story and identified Lee as the man he had seen.

(8) Jim Marrs, Crossfire: The Plot That Killed Kennedy (1989)

One witness was Warren Reynolds, who chased Tippit's killer. He, too, failed to identify Oswald as Tippit's killer until after he was shot in the head two months later. After recovering, Reynolds identified Oswald to the Warren Commission. (A suspect was arrested in the Reynolds shooting, but released when a former Jack Ruby stripper named Betty Mooney MacDonald provided an alibi. One week after her word released the suspect, MacDonald was arrested by Dallas Police and a few hours later was found hanged in her jail cell. Neither the FBI nor the Warren Commission investigated this strange incident.

(9) Warren Reynolds was interviewed by Wesley J. Liebeler for the Warren Commission (22nd July, 1964)

Wesley Liebler: Tell us what you saw; will you, please?

Warren Reynolds: OK; our office is up high where I can have a pretty good view of what was going on. I heard the shots and, when I heard the shots, I went out on this front porch which is, like I say, high, and I saw this man coming down the street with the gun in his hand, swinging it just like he was running. He turned the corner of Patton and Jefferson, going west, and put the gun in his pants and took off, walking.

Wesley Liebler: How many shots did you hear?

Warren Reynolds: I really have no idea, to be honest with you. I would say four or five or six. I just would have no idea. I heard one, and then I heard a succession of some more, and I didn't see the officer get shot.

Wesley Liebler: Did you see this man's face that had the gun in his hand?

Warren Reynolds: Very good.

Mr. LIEBELER. Subsequent to that time, you were questioned by the Dallas Police Department, were you not?

Warren Reynolds: No.

Wesley Liebler: The Dallas Police Department never talked to you about the man that you saw going down the street?

Warren Reynolds: Now, they talked to me much later, you mean?

Wesley Liebler: OK; let me put it this way: When is the first time that anybody from any law-enforcement agency, and I mean by that, the FBI, Secret Service, Dallas Police Department, Dallas County sheriff's office; you pick it. When is the first time that they ever talked to you?

Warren Reynolds: January 21.

Wesley Liebler: That is the first time they ever talked to you about what you saw on that day?

Warren Reynolds: That's right.

Wesley Liebler: So you never in any way identified this man in the police department or any other authority, either in November or in December of 1963; is that correct?

Warren Reynolds: No; I sure didn't.

Wesley Liebler: So it can be in no way said that you "fingered" the man who was running down the street, and identified him as the man who was going around and putting the gun in his pocket?

Warren Reynolds: It can be said I didn't talk to the authorities.

Wesley Liebler: Did you say anything about it to anybody else?

Warren Reynolds: I did.

Wesley Liebler: Were you able to identify this man in your own mind?

Warren Reynolds: Yes.

Wesley Liebler: You did identify him as Lee Harvey Oswald in your own mind?

Warren Reynolds: Yes.

Wesley Liebler: You had no question about it?

Warren Reynolds: No.

Wesley Liebler: Let me show you some pictures that we have here. I show you a picture that has been marked Garner Exhibit No. 1 and ask you if that is the man that you saw going down the street on the 22d of November as you have already told us.

Warren Reynolds: Yes.

Wesley Liebler: You later identified that man as Lee Harvey Oswald?

Warren Reynolds: In my mind.

Wesley Liebler: Your mind, that is what I mean.

Warren Reynolds: Yes.

Wesley Liebler: When you saw his picture in the newspaper and on television? Is that right?

Warren Reynolds: Yes; unless you have somebody that looks an awful lot like him there.

(10) The Warren Report: Part 3, CBS Television (27th June, 1967)

Walter Cronkite: Why was Officer Tippit in Oak Cliff off his normal beat? Those who believe there was a conspiracy involving the Dallas police force have maintained that the meeting between Oswald and Tippit was not an accident, that Tippit may have been looking for Oswald or vice versa. They say Tippit should not have been where he was and should not have been alone in the squad car. Eddie Barker talked to police radio dispatcher, Murray Jackson:

Eddie Barker: Officer Jackson, a lot of critics of the Warren Report have made quite a thing out of the fact that Officer Tippit was not in his district when he was killed. Could you tell us how he happened to be out of his district?

Murray Jackson: Yes, sir. I have heard this several times since the incident occurred. He was where he was because I had assigned him to be where he was in the central Oak Cliff area. There was the shooting involving the President, and we immediately dispatched every available unit to the triple underpass where the shot was reported to have come from.

(11) Domingo Benavides, The Warren Report: Part 3, CBS Television (27th June, 1967)

As I was driving down the street, I seen this police car, was sitting here, and the officer was getting out of the car, and apparently he'd been talking to the man that was standing by the car. The policeman got out of the car, and as he walked past the windshield of the car, where it's kind of lined up over the hood of the car, where this other man shot him. And, of course, he was reaching for his gun.

And so, I was standing there, you know, I mean sitting there in the truck, and not in no big hurry to get out because I was sitting there watching everything. This man turned from the car then, and took a couple of steps, and as he turned to walk away I believe he was unloading his gun, and he took the shells up in his hand, and as he took off, he threw them in the bushes more or less like nothing really, trying to get rid of them. I guess he didn't figure he'd get caught anyway, so he just threw them in the bushes.

(12) Jim Garrison, The Warren Report: Part 3, CBS Television (27th June, 1967)

The reason for Officer Tippit's murder is simply this: It was necessary for them to get rid of the decoy in the case - Lee Oswald... Lee Oswald. Now, in order to get rid of him - so that he would not later describe the people involved in this, they had what I think is a rather clever plan. It's well known that police officers react violently to the murder of a police officer. All they did was arrange for an officer to be sent out to Tenth Street, and when Officer Tippit arrived there he was murdered, with no other reason than that. Now, after he was murdered, Oswald was pointed to, sitting in the back of the Texas Theater where he'd been told to wait, obviously.

Now, the idea was, quite apparently, that Oswald would be killed in the Texas Theater when he arrived, because he'd killed a "bluecoat." That's the way the officers in New Orleans use the phrase. "He killed a bluecoat." But the Dallas police, at least the arresting Dallas police, fooled them, because they had, apparently, too much humanity in them, and they did not kill him...

The Dallas police, apparently, at least the arresting police officers, had more humanity in them than the planners had in mind. And this is the first point at which the plan did not work completely. So Oswald was not killed there. He was arrested. This left a problem, because if Lee Oswald stayed alive long enough, obviously he would name names and talk about this thing that he'd been drawn into. It was necessary to kill him.

(13) Review by James H. Fetzer of Thomas Mallon's book, Mrs. Paine's Garage (2002)

The book endorses the idea that Oswald was responsible for an alleged attempt on the life of Major General Edwin Walker that occurred on 10 April 1963. But there are many reasons to doubt it. The situations were very different: a high-powered 30.06 rifle versus a medium-to-low powered 6.5 mm carbine; a stationary versus moving target; a miss versus two hits out of three. It is difficult to imagine how their varied circumstances could have been less suggestive of a common shooter!

Unless, of course, their politics were similar - but Walker was a right-wing general, while Kennedy was a left-wing president. Kennedy had even relieved Walker of his command in Germany! It doesn't take a rocket scientist to conclude that these shootings were not performed by the same shooter. It does provide an opportunity for Thomas Mallon to compose another book. If Lee also had a 30.06, then he had to have stored it somewhere. We can now look forward to a sequel, Mrs. Paine's Attic.

Mallon also asserts that, "Oswald took a bus and taxi back to his rooming house in Oak Cliffs, where he picked up the pistol that he used minutes later to kill the patrolman, J. D. Tippit, who stopped him at the corner of Tenth and Patton". If he were correct about this - Mallon offers no reason for thinking so! - then Oswald must have been the only assassin in history to make his escape by public transportation. He also ignores evidence that Tippit was shot with automatic(s) when Oswald was packing a revolver.

(14) Geneva White was interviewed about her husband, Roscoe White, by Harrison Edward Livingstone for the book, High Treason (1990)

White asked Tippit to drive Oswald to Redbird Airport.. .Tippit balked, suspecting they were involved in the assassination he had just heard about, and White had to shoot him right then. Oswald ran away. There is a report that an extra police shirt was found in the backseat of Tippit's car, and we surmise that this belonged to Roscoe, who changed his clothes there. It is also thought that Tippit's car was the one that stopped at Oswald's house and beeped, and then picked him up down the street.

(15) Michael Kurtz, Crime of the Century: The Kennedy Assassination From a Historians Perspective (1982)

It is difficult to accept the Warren Commission's claim that Tippit stopped Oswald because Oswald fitted the description of the suspect in the Kennedy assassination. That description was so general that it could have described thousands of individuals. Since Tippit had a view only of Oswald's rear, one wonders how he could have matched him with the suspect. Furthermore, it Tippit really suspected Oswald, he almost surely would have drawn his revolver against such a dangerous suspect. Yet, according to the commission's star eyewitness, Helen Markham, Tippit not only made no attempt to make the arrest of a lifetime, he engaged him in friendly conversation.

Neither the Warren Commission nor the House Select Committee on Assassinations tried to explore the unusual circumstances surrounding Tippit's presence in the area. Almost every other police officer in Dallas was ordered to proceed to Dealey Plaza Parkland Hospital, or Love Field Airport. Tippit alone received instructions to remain where he was, in the residential Oak Cliffs section, where no suspicion of criminal activity had been raised. The police dispatcher also ordered Tippit to be at large for any emergency that comes in," most unusual instructions, since the primary duty of all policemen is to "be at large for emergencies.

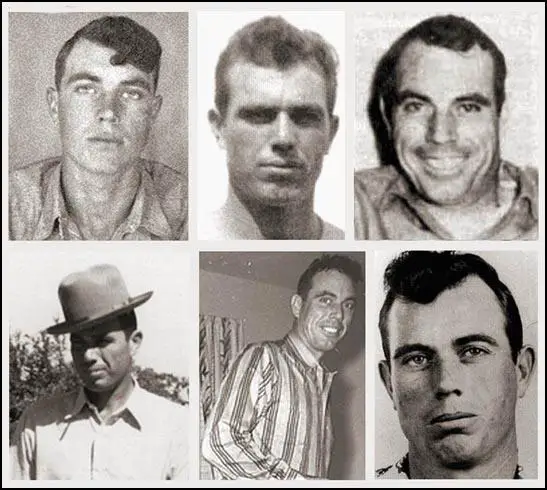

(16) Richard E. Sprague, The Taking of America (1976)

David Belin of the Warren and Rockefeller Commission is fond of saying, "Lee Harvey Oswald killed policeman Tippit. Since the case against Oswald for the Tippit slaying is so strong, it follows that Oswald also shot the President." The case against Oswald in the Tippit murder is as weak as the case against him in the JFK assassination. The most important evidence showing that Seymour and another one of the assassination team shot Tippit is the fact that six witnesses, ignored by the Warren Commission, saw two men shoot Tippit. One of them resembled Oswald. They ran away from the scene in opposite directions. Seymour ran toward the Texas Theater, throwing the planted shells up in the air so that witnesses would see and recover them. (This act would convince most people that Oswald did not shoot Tippit.) The other assassin ran in the opposite direction. There is some indication that Seymour entered the theater in a manner to draw attention and then left before the Oswald arrest. While the shells recovered were found to match Oswald's pistol, none of the bullets recovered from Tippit's body matched.