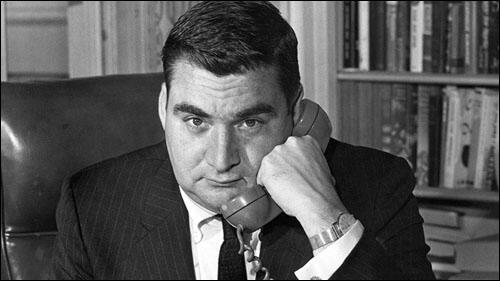

Pierre Salinger

Pierre Salinger, the son of a German mining engineer, was born in San Francisco on 14th June, 1925. His mother was a French journalist. After completing his degree at the University of San Francisco he began work as an investigative journalist with the San Francisco Chronicle.

A member of the Democratic Party he was an active supporter of Harry Truman in the 1948 Presidential Election. It was while working for the Senate Committee on the Improper Activities in Labour and Management in 1957 that he met Robert Kennedy. He joined the Kennedy inner-circle and in 1960 John F. Kennedy appointed Salinger as his press secretary. He held the post until the assassination of the president. He agreed to stay on under Lyndon B. Johnson.

In 1964 Salinger was appointed to the Senate after the death of Clair Engle of California. He served for only 148 days as he was defeating in the subsequent election. He remained active in politics and helped Robert Kennedy in his bid to become president in 1968. After Kennedy's assassination he moved to France where he worked for L'Express. This was followed by work as ABC's Paris Bureau Chief. In 1983 ABC moved to London as the network's chief foreign correspondent.

Salinger was the author of several books including With Kennedy (1966), For the Eyes of the President Only (1971), America Held Hostage: The Secret Negotiations (1983), The Dossier (1984), Above Paris (1985), Mortal Games (1989), Secret Dossier: The Hidden Agenda Behind the Gulf War (1991), An Honorable Profession: A Tribute to Robert F. Kennedy (1993), A Memoir (1995) and John F.Kennedy, Commander-in-chief (1997).

Pierre Salinger died on 16th October, 2004.

Primary Sources

(1) Pierre Salinger, With Kennedy (1966)

The convention itself produced only two crises we had not anticipated. The first was a press conference held on the first day of the convention by John B. Connally, now Governor of Texas, and Mrs. India Edwards, former chairman of the Women's Division of the Democratic National Committee. They announced to an incredulous press corps that John F. Kennedy had Addison's disease and might prove physically unfit for the ardors of the presidency. This was one of the last gasps of the sputtering drive in behalf of Lyndon B. Johnson.

(2) Pierre Salinger, With Kennedy (1966)

Following the nomination and selection of Johnson as the vice-presidential candidate Thursday night, I returned to the office and was immediately called by a number of newspaper men who were checking on a story by John S. Knight, publisher of the Knight Newspapers, which purported that Johnson had forced Kennedy to select him as the vice-presidential candidate.

Earlier that day I had gone to Bob Kennedy's room which was across from mine in the Biltmore Hotel. Ken O'Donnell was there and after I came in they were discussing the possibilities for Vice President. Bob Kennedy asked me to compute the number of electoral votes in New England and in the "solid South." I asked him if he was seriously thinking of Johnson and he said he was. He said Senator Kennedy was going over to see Johnson at 10 a.m. Ken O'Donnell violently protested about Johnson's being on the ticket and I joined Ken in this argument. Both of us felt that Senator Stuart Symington would make a better candidate but Senator Johnson seemed to be on Bob's mind. I remembered all of this later that night when I saw the news report about Johnson forcing himself on the ticket.

I called Bob Kennedy that night to check the Knight story. Bob said it was absolutely untrue. From my conversation with him, however, I gathered that the selection of Johnson had not been accomplished in the manner that the papers had reported it had. I got the distinct feeling that, at best, Senator Kennedy had been surprised when he asked Senator Johnson to run for Vice-President and Johnson accepted...

A day or two after the convention, I asked JFK for the answer to that question. He gave me many of the facts of the foregoing memo, then suddenly stopped and said: "The whole story will never be known. And it's just as well that it won't be."

(3) Pierre Salinger, With Kennedy (1966)

The publishers were generally pleased with the President's frankness -and with the honor of being invited to the White House for lunch. My files are full of letters from publishers who, on arriving home, wrote to say they had a far better understanding of the President and his problems than they had had before. One wrote me: "I will never be able to write another glib editorial attacking the President without thinking of that lunch and the great burdens of an American President."

The lunches were not without their humorous and non-humorous aspects. One publisher (I suspect he had imbibed of cocktails too freely) insisted on taking one of the gold spoons of the White House service as a "souvenir for my daughter." The publisher was sitting next to me and I fruitlessly attempted to persuade him that this would be a bad idea. The President, sitting opposite me, finally heard the conversation and it took a personal request from him to the publisher to avert the loss of the spoon.

All but one of the affairs was cordial. The exception was the Texas lunch when E. M. Dealey, publisher of the Dallas Morning News, scornfully told the President: "We need a man on horseback to lead this nation, and many people in Texas and the Southwest think that you are riding Caroline's bicycle." The other news executives listened in embarrassed silence and one of them, the publisher of the afternoon Dallas Times Herald, later sent JFK a note assuring him that Dealey spoke only for himself. "I'm sure the people of Dallas must be glad when afternoon comes," the President replied. In a later speech, he struck out at those who "look suspiciously at our neighbors and our leaders. They call for a`man on horseback' because they do not trust the people."

The same day the President was assassinated, the Dallas Morning News ran a full-page ad, paid for by "American-thinking Citizens of Dallas," accusing him of pro-Communist sympathies. The day before, a News columnist advised the President to confine his remarks in Dallas to yachting: "If the speech is about boating you will be among the warmest of admirers. If it is about Cuber, civil rights, taxes or Vietnam, there will sure as shooting be some who heave to and let go with a broadside of grapeshot in the presidential rigging."

(4) Pierre Salinger, With Kennedy (1966)

Reports had begun appearing that the United States was training a brigade for military action against Castro as early as October 1960 - three months before President Kennedy took office. The first article had appeared in a Guatemalan newspaper, La Hora, and had swiftly been followed by stories in The Nation, Time, the New York Times, and other U.S. newspapers.

In the weeks before the invasion, hardly a day passed without a story appearing in some newspaper, or broadcast over some radio or television station. It is fair to say that some of the press went after the story as if it were a scandal at city hall, or a kidnaping-not a military operation whose entire success might depend on the elements of surprise and secrecy. Newsmen sought out Cuban refugees in cafes and hotel lobbies in Miami to pump them for the latest news from relatives serving with the brigade. Through such "enterprise," they were able to publish much information of tactical importance, including exact estimates of the brigade's strength.

The volatile leaders of the Cuban Revolutionary Council in exile - the political arm of the brigade - were just as heedless of security. Only nine days before the landing, the council's president, Dr. Jose Miro Cardona, told the press in Miami that an uprising against Castro was "imminent" .And the very next day, he appealed to Cubans still in their homeland to take up arms against the dictator. The only information Castro didn't have have then was the exact time and place of the invasion.