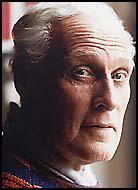

Willem Oltmans

Willem Oltmans, the son of a lawyer, was born Huizen, the Netherlands, on 10th June, 1925. Oltmans studied at Nijenrode before going to Yale University (1948-50) where he met William F. Buckley.

In 1952 Oltmans became a journalist with the Amsterdam Times. Later he joined United Press International. In June 1956 he interviewed President Sukarno of Indonesia. The article that he produced was considered too sympathetic to the nationalist leader. At the time the CIA was supporting the PRRI-Permesta rebellion in Sulawesi.

Oltmans argued that Netherlands New Guinea should be given full independence. Oltmans' actions resulted in creating some dangerous enemies. This included Joseph Luns, the Dutch minister of foreign affairs. According to Oltmans, Luns did what he could to sabotage his journalistic career.

In 1958 Oltmans emigrated to the United States and worked for several media outlets in the Netherlands. Oltmans created controversy by travelling to several communist countries including Cuba and North Vietnam. Oltmans developed a reputation as a radical journalist. It was later revealed that Oltmans' network in the 1960s had been infiltrated by CIA agent, Werner Verrips.

On 5th April 1961, Joseph Luns arranged for the New Guinea Council to take office in Netherlands New Guinea. President Sukarno threatened to invade this territory that he felt believed belonged to Indonesia and on 15th August, 1962, he ordered full mobilisation of his army. Oltmans claimed to have prevented a Dutch war against Indonesia over New Guinea by sending a memo to President John F. Kennedy. Whatever the truth of this statement, Kennedy, against CIA advice, applied pressure on the Dutch government to hand over the territory to a temporary UN administration (UNTEA). On May 1, 1963, Indonesia took control of the country.

As David Kaiser pointed out in American Tragedy (2000) "Kennedy had courted President Sukarno - who at home balanced his large domestic Communist party with a pro-Western army - and his administration had supported the transfer of West New Guinea from Dutch to Indonesian sovereignty and successfully mediated the dispute between the two nations... In the week before his death, Kennedy had decided to visit Indonesia in the spring of 1964." After John F. Kennedy was assassinated, President Lyndon Johnson cancelled the visit and in December 1964 he cut off all aid to Indonesia.

In January 1964, met Oltmans met Marguerite Oswald, the mother of Lee Harvey Oswald on a plane. According to Russ Baker: "She mentioned to him her suspicions about the fact that the Dallas police had interrogated her at length about her son but failed to record the important biographical details she provided them. She told Oltmans that she suspected a conspiracy at work. From that moment forward, in his telling, Oltmans was hooked on the JFK mystery."

In 1968 Oltmans became involved in the investigation carried out byJim Garrison. Later that year he interviewed George de Mohrenschildt and remained in touch with them in the years that followed. B points out that: "In early 1976 de Mohrenschildt sent him a few pages of a manuscript about his life, with an emphasis on his interactions with Oswald. Oltmans edited the incomplete and stiffly written pages and sent them back to de Mohrenschildt."

In February 1977, Oltmans met George de Mohrenschildt for lunch in Dallas. Oltmans later told the House Select Committee on Assassinations: "I couldn't believe my eyes. The man had changed drastically... he was nervous, trembling. It was a scared, a very, very scared person I saw. I was absolutely shocked, because I knew de Mohrenschildt as a man who wins tennis matches, who is always suntanned, who jogs every morning, who is as healthy as a bull."

According to Oltmans, George de Mohrenschildt confessed to being involved in the assassination of John F. Kennedy. "I am responsible. I feel responsible for the behaviour of Lee Harvey Oswald... because I guided him. I instructed him to set it up." Oltmans claimed that de Mohrenschildt had admitted serving as a middleman between Lee Harvey Oswald and H. L. Hunt in an assassination plot involving other Texas oilmen, anti-Castro Cubans, and elements of the FBI and CIA.

Oltmans told the HSCA: "He begged me to take him out of the country because they are after me." On 13th February 1977, Oltmans took de Mohrenschildt to his home in Amsterdam where they worked on his memoirs. Over the next few weeks de Mohrenschildt claimed he knew Jack Ruby and argued that Texas oilmen joined with intelligence operatives to arrange the assassination of John F. Kennedy.

Willem Oltmans arranged for George de Mohrenschildt to meet a Dutch publisher and the head of Dutch national television. The two men then traveled to Brussels. When they arrived, Oltmans mentioned that an old friend of his, a Soviet diplomat, would be joining them a bit later for lunch. De Mohrenschildt said he wanted to take a short walk before lunch. Instead, he fled to a friend's house and after a few days he flew back to the United States. He later accused Oltmans of betraying him. Russ Baker suggests in his book Family of Secrets: "Perhaps, and this would be strictly conjecture, de Mohrenschildt saw what it meant that he, like Oswald, was being placed in the company of Soviets. He was being made out to be a Soviet agent himself. And once that happened, his ultimate fate was clear."

The House Select Committee on Assassinations were informed of George de Mohrenschildt's return to the United States and sent its investigator, Gaeton Fonzi, to find him. Fonzi discovered he was living with his daughter in Palm Beach. However, Fonzi was not the only person looking for de Mohrenschildt. On 15th March 1977 he had a meeting with Edward Jay Epstein that had been arranged by the Reader's Digest magazine. Epstein offered him $4,000 for a four-day interview.

On 27th March, 1977, George de Mohrenschildt arrived at the Breakers Hotel in Palm Beach and spent the day being interviewed by Epstein. According to Epstein, they spent the day talking about his life and career up until the late 1950s.

Two days later Edward Jay Epstein asked him about Lee Harvey Oswald. As he wrote in his diary: "Then, this morning, I asked him about why he, a socialite in Dallas, sought out Oswald, a defector. His explanation, if believed, put the assassination in a new and unnerving context. He said that although he had never been a paid employee of the CIA, he had "on occasion done favors" for CIA connected officials. In turn, they had helped in his business contacts overseas. By way of example, he pointed to the contract for a survey of the Yugoslavian coast awarded to him in 1957. He assumed his "CIA connections" had arranged it for him and he provided them with reports on the Yugoslav officials in whom they had expressed interest."

Epstein and de Mohrenschildt, broke for lunch and decided to meet again at 3 p.m. George De Mohrenschildt returned to his room where he found a card from Gaeton Fonzi, an investigator working for the House Select Committee on Assassinations. George De Mohrenschildt's body was found later that day. He had apparently committed suicide by shooting himself in the mouth.

On 11th May, 1978, Jeanne de Mohrenschildt gave an interview to the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, where she said that she did not accept that her husband had committed suicide. She also said that she believed Lee Harvey Oswald was an agent of the United States, possibly of the CIA, and that she was convinced he did not kill John F. Kennedy. She then went onto say: "They may get me too, but I'm not afraid... It's about time somebody looked into this thing."

Willem Oltmans produced five volumes of autobiography: Memoires: 1925-1953 (1985), Memoires: 1953-1957 (1986), Memoires, 1957-1959 (1987), Memoires, 1959-1961 (1988) and Memoires: 1961-1963 (1997).

In 2000 Oltmans won his legal case against the Dutch government. The jury agreed that the government conspired to keep him out of work, for which it had to pay him 8 million guilders in damages.

Willem Oltmans died of cancer in Amsterdam on 30th September, 2004.

Primary Sources

(1) Gaeton Fonzi, The Last Investigation (1993)

Late Monday afternoon, on March 28th, I received a call from Tanenbaum. The House was scheduled to vote that Wednesday on the reauthorization bill and the Committee members as well as the top staff counsel had been spending most of their time lobbying among the individual lawmakers for support. As they discovered, while many of the Congressmen didn't care for Gonzalez, he was part of the club. Some members even resented Sprague - viewed by a least one Congressman as "just a clerk" - for having beaten out Gonzalez.

That Monday, Gonzalez himself had been on the House floor ranting again about Sprague's "insubordination" and even distributing copies of a "Dear Colleague" letter to every House member urging that the Committee be dropped. He was thirsting for revenge.

I asked Tanenbaum how it looked.

"It depends on who you talk to what time of the day." He did not sound optimistic. "Anyway, Wednesday is the day. We'll know one way or the other."

We talked about the situation for a while and then I told Tanenbaum that while waiting around, I had discovered a CIA agent named J. Walton Moore running an overt domestic division office in Dallas. Moore had been there since the time of the Kennedy assassination and, there were some telling hints in his personality and activities. On the off-chance that Moore might be Maurice Bishop, I asked a friend of mine, a local reporter, to have a surreptitious photograph of Moore taken so I could show it to Veciana. (As it turned out, Moore did not resemble Bishop and Veciana confirmed that he wasn't.)

At any rate, I was telling Tanenbaum of my plans to have the photograph taken. I told him that Moore was additionally interesting because he had been in touch with George de Mohrenschildt, a much traveled oil consultant with mysterious connections. As mentioned earlier, while living in Dallas, de Mohrenschildt had befriended the Oswalds as soon as they had returned from Russia.

"By the way," Tanenbaum said, "I just got a call from the Dutch journalist, Willem Oltmans. He's the guy I was telling you about."

But Tanenbaum needn't have, because Oltmans had already gone national - doing on various television interviews, and then going to Washington to tell his story to the Committee. He had befriended de Mohrenschildt and claimed that de Mohrenschildt had confessed that he was part of a "Dallas conspiracy" of oil men and Cuban exiles with "a blood debt to settle." De Mohrenschildt admitted, Oltmans said, that Oswald "acted at his guidance and instruction."

De Mohrenschildt had apparently suffered a nervous breakdown at the time he was talking with Oltmans, but he left a hospital in Dallas to travel with Oltmans to Europe reportedly to negotiate book and magazine rights to his story. Then in Brussels, Oltmans claimed, de Mohrenschildt ran away from him and disappeared.

Now Tanenbaum told me that Oltmans had just called him from California. Oltmans said that in tracking de Mohrenschildt he found that de Mohrenschildt could be reached in Florida. Tanenbaum gave me the phone number. Now Tanenbaum really had something for me.

That afternoon, I checked out the number. It was listed to a Mrs. C.E. Tilton III in Manalapan, a small strip of a town on the ocean south of Palm Beach noted for its wealthy residents. Mrs. Tilton, I discovered, was the sister of one of de Mohrenschildt's former wives. I decided it would be best if I could contact him directly rather than by telephone and so it was early on March 29th, 1977, when I went looking for George de Mohrenschildt in Manalapan.

(2) Willem Oltmans interviewed by Robert Tanenbaum (4th January 1977)

Robert Tanenbaum: What was the reason he told you about going to commit suicide?

William Oltmans: One of the reasons was, I found it in my notes, that he doesn't want his children to look upon, to their father for the rest of their life as having been involved, directly involved in the killing of President Kennedy. He would say - and I have notes - "I would rather kill myself than let my children" - and he called not only his daughter Alexandra, but also his brother, Professor de Mohrenschildt, who is in California. He said, "My brother and daughter, I don't want to have to live the rest of their lives by this thing." You know, that he was involved. "I would rather shoot myself." He told me that various times."

Robert Tanenbaum: All right, sir. So, up until the time that you left New York City from John F. Kennedy Airport, did you have any other conversations with him with regard to the assassination of the President?

William Oltmans: Yes, repeatedly.

Robert Tanenbaum: Now, again in substance, tell us what, if anything George de Mohrenschildt told you - this is up until the time you were in New York City - about the assassination.

William Oltmans: Sir, pages and pages. I will...

Robert Tanenbaum: In substance, will you tell us what he said, please.

William Oltmans: Each time he would reveal something else....

Robert Tanenbaum: Did you have any conversations of substance with him in New York?

William Oltmans: Not at all. New York, talked a bit, but not in London.

Robert Tanenbaum: Up until this time, had he ever mentioned Jack Ruby or H. L. Hunt?

William Oltmans: Yes.

Robert Tanenbaum: Up until this time?

William Oltmans: Yes, I forgot all about that.

Robert Tanenbaum: Would you please tell us that, then.

William Oltmans: O.K. You see, in Dallas, in the many talks I had with him about going, I asked him point blank, "Did you know Ruby?"

"Yes."

"Have you been in Ruby's Bar?"

"Yes."

"Then what happened to Oswald. If Oswald set up the Kennedy Assassination, he must have had a lot of money."

De Mohrenschildt, with a devilish laugh said "He wasn't long enough around to get the money."

Then I said, "But who would pay?"

You see, he talked in circles. He was still talking in circles. He was coming around to talking, but when I asked him, who would put up that kind of money, he said, well, he would reply, "Well, did you see the letter of Oswald, was released by the FBI, to Hunt? Now, why do you think Oswald would write to Mr. H. L. Hunt?"

Then I said "Do you know Hunt, have you known him?"

He said, "I knew him for 20 years. I was very close with him. I went to all his parties."

You see, de Mohrenschildt clearly indicated that the money had come from, that his contacts were "upwards to Hunt, and downwards to Oswald."

(3) Jim Marrs, Crossfire: The Plot that Killed Kennedy (1990)

During their stay in Washington, the DeMohrenschildts visited in the home of Jackie Kennedy's mother, now Mrs. Hugh D. Auchincloss, who, according to an unpublished book by DeMohrenschildt, said; "Incidentally, my daughter Jacqueline never wants to see you again because you were close to her husband's assassin."

Returning to Haiti, the DeMohrenschildt's problems there increased to the point that in 1967 they were forced to sneak away from the island aboard a German freighter, which brought them to Port Arthur, Texas. Here, according to Jeanne in a 1978 interview with this author, the DeMohrenschildts were met by an associate of former Oklahoma senator and oilman Bob Kerr. The returning couple were extended the hospitality of Kerr's home.

By the 1970s, the DeMohrenschildts were living quietly in Dallas, although once they were questioned by two men who claimed to be from Life magazine. A check showed the men were phonies.

DeMohrenschildt seemed content to teach French at Bishop College, a predominantly black school in south Dallas. Then in the spring of 1976, George, who suffered from chronic bronchitis, had a particularly bad attack. Distrustful of hospitals, he was persuaded by someone-Jeanne cannot today recall who-to see a newly arrived doctor in Dallas named Dr. Charles Mendoza. After several trips to Mendoza in the late spring and summer, DeMohrenschildt's bronchial condition improved, but he began to experience the symptoms of a severe nervous breakdown. He became paranoid, claiming that "the Jewish Mafia and the FBI" were after him.

Alarmed, Jeanne accompanied her husband to Dr. Mendoza and discovered he was giving DeMohrenschildt injections and costly drug prescriptions. She told this author: " When I confronted (Mendoza) with this information, as well as asking him exactly what kind of medication and treatments he was giving George, he became very angry and upset. By then, I had become suspicious and started accompanying George on each of his visits to the doctor. But this physician would not allow me to be with George during his treatments. He said George was gravely ill and had to be alone during treatments."

Jeanne said her husband's mental condition continued to deteriorate during this time. She now claims: "I have become convinced that this doctor, in some way, lies behind the nervous breakdown George suffered in his final months."

The doctor is indeed mysterious. A check with the Dallas County Medical Society showed that Dr. Mendoza first registered in April 1976, less than two months before he began treating DeMohrenschildt and at the same time the House Select Committee on Assassinations was beginning to be funded.

Mendoza left Dallas in December, just a few months after DeMohrenschildt refused to continue treatments, at the insistence of his wife. Mendoza left the society a forwarding address that proved to be nonexistent. He also left behind a confused and unbalanced George DeMohrenschildt.

During the fall of 1976 while in this unbalanced mental state, DeMohrenschildt completed his unpublished manuscript entitled, I Am a Patsy! I Am a Patsy! after Oswald's famous remark to newsmen in the Dallas police station. In the manuscript, DeMohrenschildt depicts Oswald as a cursing, uncouth man with assassination on his mind, a totally opposite picture from his descriptions of Oswald through the years.

The night he finished the manuscript, DeMohrenschildt attempted suicide by taking an overdose of tranquilizers. Paramedics were called, but they declined to take him to a hospital. They found DeMohrenschildt also had taken his dog's digitalis, which counteracted the tranquilizers.

Shortly after his attempted suicide, Jeanne committed her husband to Parkland Hospital in Dallas, where he was subjected to electroshock therapy. To gauge his mental condition at this time, consider what he told Parkland roommate Clifford Wilson: "I know damn well Oswald didn't kill Kennedy-because Oswald and I were together at the time." DeMohrenschildt told Wilson that he and Oswald were in downtown Dallas watching the Kennedy motorcade pass when shots were fired. He said that at the sound of shots Oswald ran away and DeMohrenschildt never saw him again."

This story, which was reported in the April 26, 1977, edition of the National Enquirer as "Exclusive New Evidence," is untrue since both George and Jeanne were at a reception in the Bulgarian embassy in Haiti the day Kennedy was killed. But the incident serves to illustrate George DeMohrenschildt's mental condition at the time.

In early 1977, DeMohrenschildt, convinced that evil forces were still after him, fled to Europe with Dutch journalist Willems Oltmans, who later created a furor by telling the House Select Committee on Assassinations that DeMohrenschildt claimed he knew of Oswald's assassination plan in advance.

However, DeMohrenschildt grew even more fearful in Europe. In a letter found after his death, he wrote: "As I can see it now, the whole purpose of my meeting in Holland was to ruin me financially and completely."

In mid-March DeMohrenschildt fled to a relative's Florida home leaving behind clothing and other personal belongings. It was in the fashionable Manalapan, Florida, home of his sister-in-law, that DeMohrenschildt died of a shotgun blast to the head on March 29, 1977, just three hours after a representative of the House Select Committee on Assassinations tried to contact him there.

Earlier that day, he had met author Edward J. Epstein for an interview. In a 1983 Wall Street Journal article, Epstein wrote that DeMohrenschildt told him that day that the CIA had asked him "to keep tabs on Oswald."

However, the thing that may have triggered DeMohrenschildt's fear was that Epstein showed him a document that indicated George DeMohrenschildt might be sent back to Parkland for further shock treatments, according to a statement by Attorney David Bludworth, who represented the state during the investigation into DeMohrenschildt's death.

Although several aspects of DeMohrenschildt's death caused chief investigator Capt. Richard Sheets of the Palm County Sheriff's Office to term the shooting "very strange," a coroner's jury quickly ruled suicide.

It is unclear if Oltmans knew of DeMohrenschildt's mental problems at the time he made his statements, but in later years, Jeanne told the newsman: "If George's death was engineered, it is because you focused such attention on my husband that the real conspirators decided to eliminate him just in case George actually knew something, just like so many others involved in the assassination."

(4) Dick Russell, New Times Magazine (24th June, 1977)

Like Fitzgerald's Gatsby, Baron George Sergei de Mohrenschildt was borne back ceaselessly into the past. In June 1976, a sultry day in Dallas, he had stood gazing out the picture window of his second-story apartment, talking casually about a young man who used to curl up on the couch with the Baron's Great Danes.

"No matter what they say, Lee Harvey Oswald was a delightful guy," de Mohrenschildt was saying. "They make a moron out of him, but he was smart as hell. Ahead of his time really, a kind of hippie of those days. In fact, he was the most honest man I knew. And I will tell you this - I am sure he did not shoot the president."

Nine months later, on March 29, one hour after an investigator for the House Assassinations Committee left a calling-card with his daughter, the Baron apparently put a shotgun to his head in Palm Beach, Florida. In his absence came forward a Dutch journalist and longtime acquaintance, Willem Oltmans, with the sensational allegation that de Mohrenschildt had admitted serving as a middleman between Oswald and H. L. Hunt in an assassination plot involving other Texas oilmen, anti-Castro Cubans, and elements of the FBI and CIA.

But how credible was de Mohrenschildt? As an old friend in Dallas' Russian community, George Bouhe, once put it: "He's better equipped than anybody to talk. But we have an old Russian proverb that will always apply to George de Mohrenschildt: "The soul of the other person is in the darkness."'

Intrigue and oil were the two constants in the Baron's life. He was an emigrant son of the Czarist nobility who spoke five languages fluently and who, during the Second World War, was rumored to have spied for the French, Germans, Soviets and Latin Americans (the CIAs predecessor, the OSS, turned down his application). After the war, he went on to perform geological surveys for major U.S. oil companies all over South America, Europe and parts of Africa. He became acquainted with certain of Texas' more influential citizens - oilman John Mecom, construction magnates George and Herman Brown. In Mexico, he gained audience in 1960 with Soviet First Deputy Premier Anastas Mikoyan. In 1961 he was present in Guatemala City - by his account, on a "walking tour" - when the Bay of Pigs troops set out for Cuba.

Finally, when Lee and Marina Oswald returned to Texas from the Soviet Union in June 1962, the Baron soon became their closest friend. Why? Why would a member of the exclusive Dallas Petroleum Club take under his wing a Trotsky-talking sheet-metal worker some 30 years his junior?

The Warren Commission took 118 pages of his testimony to satisfy itself of de Mohrenschildt's benign intent, but among critics the question persisted: Was the Baron really "baby-sitting" Oswald for the CIA? While de Mohrenschildt told the commission he'd never served as any government's agent "in any respect whatsoever," a CIA file for the commission, declassified in 1976, admits having used him as a source. In the course of several meetings with a man from its Dallas office upon de Mohrenschildt's return from Yugoslavia late in 1957, "the CIA representative obtained foreign intelligence which was promptly disseminated to other federal agencies in ten separate reports."The Dallas official, according to the file, maintained "informal occasional contact" with the Baron until the fall of 1961.

The Warren Commission volumes, however, contain only passing reference in de Mohrenschildt's testimony to a government man named "G. Walter Moore." His true name was J. Walton Moore, and he had served the CIA in Dallas since its inception in 1947.

In two brief, cryptic interviews with me in the 18 months before his death, de Mohrenschildt claimed he would not have struck up his relationship with Oswald "if Jim Moore hadn't told me Oswald was safe." The Baron wouldn't elaborate on that statement, except to hint that it constituted some kind of clearance.

J. Walton Moore is now a tall, white-haired man in his middle sixties, who continues to operate out of Dallas' small CIA office. Questioned at his home one summer evening in 1976 about de Mohrenschildt's remarks, he conceded knowing the Baron as a "pleasant sort of fellow" who provided "some decent information" after a trip to Yugoslavia. "To the best of my recollection, I hadn't seen de Mohrenschildt for a couple of years before the assassination," Moore added. "I don't know where George got the idea that I cleared Oswald for him. I never met Oswald. I never heard his name before the assassination."

For sure, the CIA did maintain an interest in de Mohrenschildt at least through April 1963. That month, Oswald left Texas for New Orleans and de Mohrenschildt prepared to depart for a lucrative geological survey contract in Haiti. On April 29, according to a CIA Office of Security file, also declassified in 1976, "[Deleted] Case Officer had requested an expedite check of GEORGE DE MOHRENSCHILDT for reasons unknown to Security."

There is one alleged ex-CIA contract employee, now working for an oil company in Los Angeles, prepared to testify that de Mohrenschildt was the overseer of an aborted CIA plot to overthrow Haitian President Francois ("Papa Doc") Duvalier in June 1963. The existence of such a plot was examined, but apparently couldn't be substantiated, by the Church Committee. Herb Atkin is sure the plot did exist.

"I knew de Mohrenschildt as Philip Harbin," Atkin said when contacted by telephone a few days after the Baron's suicide. "A lot of people in Washington have claimed that Harbin did not exist. But he's the one that ran me from the late fifties onward. I'm certain that de Mohrenschildt was my case officer's real name."

If so, the Harbin alias may have a readily identifiable origin. De Mohrenschildt's fourth wife, Jeanna, was born in Harbin, China.

One summer day in 1976, still in her bathrobe, she sat at a dining room table cluttered with plants and dishes and watched her husband begin to pace the floor. "Of course, the truth of the assassination has not come out," she said. "It will never come out. But we know it was a vast conspiracy."

The Baron turned to face her. "Oswald," he said, "was a harmless lunatic."

At our first interview, I had asked de Mohrenschildt what he knew about the recurring reports of Oswald in the presence of Cubans. He had nodded agreement. "Oswald probably did not know himself who they were," he replied. "I myself was in a little bit of danger from those Cubans, but I don't know who they are. Criminal lunatics."When I broached the subject now in the presence of his wife, de Mohrenschildt said something to her in Russian. She then answered for him: "That's a different story. But one must examine the anti-Castro motive of the time. After the Bay of Pigs."

A few months later, de Mohrenschildt was committed by his wife to the psychiatric unit of Parkland Memorial Hospital. There were rumors of a book naming CIA names in connection with Oswald, squirreled away with his wife's attorney. According to journalist Oltmans, upon leaving the hospital de Mohrenschildt told him: "They're going to kill me or put me away forever. You've got to get me out of the country." In March, the Baron took a leave-of-absence from his French professorship at Dallas' virtually all-black Bishop College. He flew with Oltmans to Belgium, wandered away during lunch, and wound up in Florida at his daughter's home. There, a tape machine being used to transcribe a television program is said to have recorded his suicide.

(5) Russ Baker, Family of Secrets (2009)

In January 1976, he (George de Mohrenschildt) wrote to Willem Oltmans, a freelance Dutch television reporter whom he had met eight years earlier. Oltmans's reason for maintaining contact with de Mohrenschildt has been a subject of some speculation, including among his Dutch media colleagues. His profile at times appears less that of the typical left-leaning Dutch journalist and more suggestive of a U.S. intelligence agent. Former colleagues of Oltmans, who is deceased, described him to me as a complex and mysterious figure. As will become clear, Oltmans was a cipher to one and all, sometimes seeming to be determined to expose the truth, and sometimes to do the opposite. Perhaps he was something of a free agent, pursuing a particular course yet unhappy about it. But one thing is certain: just as de Mohrenschildt helped steer Oswald, to a lesser extent Oltmans did the same for de Mohrenschildt.

Oltmans was the son of an affluent family with a history in colonial Indonesia. A Dutch citizen, he had graduated in the same Yale University class as William F. Buckley, and was a strident anti-Communist. Though he had no apparent connections to Dallas, Oltmans was drawn into conservative circles in that city shortly after Allen Dulles's forced resignation and about the time that the CIA's Dallas officer J. Walton Moore began talking to George de Mohrenschildt about Lee Harvey Oswald. Oltmans's reason for visiting at that time was an invitation to give occasional lectures to women's groups. Those female auxiliaries played important support roles in Dallas's highly politicized and arch-conservative elite, as did the White Russian community, the independent oilmen, and the military contractors and intelligence officers.

Oltmans's name appears on a schedule of upcoming speakers at the Dallas Woman's Club published in the Dallas Morning News in October 1961. The leadoff speaker for that season: Edward Tomlinson, "roving Latin American editor" for Reader's Digest.

Oltmans's next invitation to speak to the Dallas ladies appears to have been in January 1964, shortly after Kennedy's assassination. At that time, Oltmans met Lee Harvey Oswald's mother on a plane (a coincidence, he said). She mentioned to him her suspicions about the fact that the Dallas police had interrogated her at length about her son but failed to record the important biographical details she provided them. She told Oltmans that she suspected a conspiracy at work.

From that moment forward, in his telling, Oltmans was hooked on the JFK mystery. He interviewed George and Jeanne de Mohrenschildt in 1968 and 1969 and remained in touch with them in the years that followed. George de Mohrenschildt got so comfortable with Oltmans that in early 1976 de Mohrenschildt sent him a few pages of a manuscript about his life, with an emphasis on his interactions with Oswald. Oltmans edited the incomplete and stiffly written pages and sent them back to de Mohrenschildt.