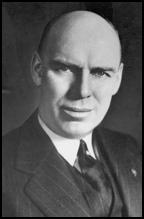

Owen Brewster

Owen Brewster was born in Penobscot County, Maine, on 22nd February, 1888. He graduated from Bowdoin College, Brunswick, in 1909, and from the law department of Harvard University in 1913. He was admitted to the bar and worked as a lawyer in Portland, Maine.

A member of the Republican Party he served as Governor of Maine (1925-1929). An unsuccessful candidate for election to the Seventy-third Congress in 1932; he was elected to the Seventy-fourth, Seventy-fifth, and Seventy-sixth Congresses (January 3, 1935-January 3, 1941). Brewster was elected to the United States Senate in 1940 and took his seat on 3rd January, 1941.

Brewster was chairman of the Senate War Investigating Committee. In 1946 Brewster announced that he was very concerned that the government had given Howard Hughes $40m for the development and production of two aircraft that had never been delivered. Brewster also pointed out the President Franklin D. Roosevelt had overruled his military experts in order to hand out the contracts to Hughes for the F-11 and HK-1 (also known as the Spruce Goose).

Brewster also pointed out that Hughes had provided "softening-up parties" for government officials. Howard paid movie starlets $200 to attend these parties. Their duties included swimming nude in Hughes's swimming pool. Julius Krug, the chief of the War Production Board, was someone who often attended these parties. One congressman who was also a frequent guest at Hughes's home claimed: "If those girls were paid two hundred dollars, they were greatly underpaid".

Howard Hughes, accused of corruption, leaked information to journalists, Drew Pearson and Jack Anderson that Brewster was being paid by Pan American Airways (Pan Am) to cause trouble. According to Hughes, Pan Am was trying to persuade the United States government to set up an official worldwide monopoly under its control. Part of this plan was to force all existing American carriers with overseas operations to close down or merge with Pan Am. As the owner of Trans World Airlines, Hughes posed a serious threat to this plan. Hughes claimed that Brewster had approached him and suggested he merge Trans World with Pan Am. When Hughes refused Brewster began a smear campaign against him.

Drew Pearson and Jack Anderson believed Hughes and began their own campaign against Brewster. They reported that Pan Am had provided Bewster with free flights to Hobe Sound, Florida, where he stayed free of charge at the holiday home of Pan Am Vice President Sam Pryor. These charges were repeated by Hughes when he appeared before the Senate War Investigating Committee. He also accused Brewster of trying to blackmail him into merging Trans World with Pan Am. Brewster denied the charge but it helped divert attention away from the charge that Hughes had wasted $40m of government money.

The Senate War Investigating Committee never completed its report on the non-delivery of the F-11 and the HK-1. The committee stopped meeting and was eventually disbanded.

In 1950 Brewster joined other right-wing members of Congress, including Joseph McCarthy, Richard Nixon, J. Parnell Thomas, Harold Velde, Francis E. Walter, John Rankin, John Wood, and Karl Mundt in their campaign to remove "communists" from public life. When McCarthy claimed that Drew Pearson was a communist in a speech in the Senate on 15th December, 1950, Brewster had 75,000 copies printed and sent them out to everyone on his mailing list.

Brewster was a strong supporter of General Douglas MacArthur and urged President Harry S. Truman to allow American troops to cross the Chinese border. He also suggested that MacArthur should be allowed to use atomic bombs in the Korean War.

Drew Pearson and Jack Anderson continued their campaign against Brewster and in the 1952 election he was defeated by 3,000 votes.

Owen Brewster died in Boston, Massachusetts, on 25th December, 1961, and was later interned in Mount Pleasant Cemetery, Dexter, Maine.

Primary Sources

(1) Jack Anderson, Confessions of a Muckraker (1979)

My mentor's sympathies, then, lay with (Howard) Hughes, but Drew (Pearson) felt stranded in an unsatisfying posture. It was his nature to want to play an important part in the great political brawls of the time, to put his mark on them, to help shape their outcome toward the benefit of his causes or the distress of his foes. Yet he would not take Brewster's side and could not take Hughes's. For though Hughes was probably the victim of an unsavory gang-up, his own conduct in the matter was too shabby to defend and he was not even making a fight of it himself. Grumbling at each day's leaks, Drew held back, watching the thing spin, looking for a handle to pick it up by.

At this point in his disintegrating fortunes, Howard Hughes phoned Drew from one of his West Coast redoubts. He had long considered Pearson to be journalism's leading molder of public opinion and the man most knowledgeable about the Byzantine twists of conspiratorial Washington. And since Drew's animus against Hughes's tormentors was clear, there was a mutuality of interest present that encouraged him to seek Drew's help and advice.

In the manner of cornered men whose expense accounts have already been made public, Hughes admitted to misdemeanors but pled innocent to felonies. He had indeed wined and wenched government officials and military brass, sometimes to excess. It was necessary, he said; his competitors did it, and as a relative newcomer trying to buck long-entrenched interests and liaisons, he had to play the game in order to get a hearing on his proposals. He had never looked on aviation as a moneymaker, he insisted; he was in it because he had a passion for it. He yielded to no man in his mastery of the dark arts of making money, as the astronomical profits of his other businesses showed, but in aviation, he had lost $14 million in thirteen years.

Then he got to the nub: three months before, Brewster had attempted to lobby him in behalf of Pan Am, he said, and having failed, they were both out to destroy him. Pan Am had put great pressure on him to merge Trans World with Pan Am and co-sponsor the chosen-instrument plan. Brewster himself had told him at the Mayflower Hotel that the probe would be dropped if he joined forces with Pan Am.

(2) Drew Pearson, Washington Merry-Go-Round (18th September, 1950)

Senator Brewster in 1947 was chairman of the powerful Senate War Investigating Committee. He was also the bosom friend of Pan American Airways. Brewster and Pan American wanted Howard Hughes's TWA to consolidate its overseas lines with Pan Am. This Hughes refused to do. Whereupon Brewster investigated Hughes, and, during the period when he was before Brewster's Senate committee, Hughes's telephone wire and that of his attorneys were tapped, apparently under the off-stage direction of Henry Grunewald, who admits that at various times he checked telephone wires for Pan American Airways.

Grunewald and others deny this. Nevertheless this is the conclusion which Senators are forced to arrive at. No wonder businessmen who come to Washington are worried about talking over telephones. They never know when some competitor, perhaps with the cooperation of a Senate committee, is listening in. Yet this is supposed to be the capital of the USA not Moscow.

(3) Drew Pearson, Washington Merry-go-round (18th September, 1950)

My first encounter with Hughes was awesome enough, given my limited experience as Drew's resident expert on the Senate. Hughes wanted my advice, however humble, about going up against Maine Senator Owen Brewster, a rascal who was preparing to fire a political broadside against the Hughes industrial empire. Hughes was supposed to have built two revolutionary aircraft for the Pentagon - a photo-reconnaissance spy plane called the F-II, and a giant plywood cargo seaplane nicknamed the "Spruce Goose." They were two wartime contracts that cost the taxpayers $40 million. Now it was 1947, the war was well over, and Hughes had not yet finished either plane.

Normally this would have been grist for Drew's mill - a defense contractor cheating the taxpayers, hints of political string pulling, two projects running way over budget. But Drew had satisfied himself that Hughes and his designers had done their level best to develop the two planes that were almost ready to fly. A passionate aviator and inventor, Hughes had an irrepressible emotional investment in both projects that went beyond the contracts. He was personally absorbing the cost overruns.

The real story in Drew's judgment was Brewster's motive. His political guns were aimed at the F-II and the Spruce Goose. But his target was Trans World Airlines, and his objective was to defame its majority stockholder, Howard Hughes. Brewster was the chief water carrier in the Senate for the rival Pan American Airlines. The two giants of the air were duking it out for the exclusive right to fly international routes from the United States. Under a regulatory scheme called the "chosen instrument," one airline would be selected to fly the international routes and would be subsidized by the taxpayers. Brewster was pushing through a law to give Pan Am that worldwide monopoly, and Hughes stood in his way.

(4) Jack Anderson, Confessions of a Muckraker (1979)

During these days I tried to probe Brewster's strengths and weaknesses with something of the objectivity of a pug studying the ring habits of his next opponent. I looked first for those personal weaknesses that Drew had taught me to cherish in an adversary: overweaning vanity, bumbling pomposity, addiction to creature comforts, a tendency to alcoholic indiscretion, the heedless pursuit of venery.

I found nothing. Brewster was unpretentious of manner and disciplined in utterance. He did not drink at all, or even smoke, and in his relations with the habitually exploited Capitol Hill secretary, I found no departure from the most punctilious code of chivalry. His daily routine was a rigorous model of hard work; his life at home was frugal. Even his two culpable indulgences had a saving grace about them: the corporate plane rides were no doubt prized for the working time they saved him, and when he occupied Sam Pryor's Hobe Sound lodge for Thanksgiving vacations, he brought his own turkey and cleaned the place up afterward. As far as our spies could ascertain, his nightly revels at his Mayflower Hotel apartment were confined to doing his laundry; nylon wash-and-wear shirts had recently been introduced and Brewster had purchased one; each night he washed out his white shirt, hung it up to dry and the next morning put it on again, ready to face, impeccably, the Washington power structure. Such men do not make easy opponents.

It was Brewster who showed me the advantages of being born ugly. Ugly he was - billiard-bald on top, cheerless-eyed, meaty-lipped, an appearance dark and gloomy. For him, the ballot box would have seemed the least likely springboard to success. Yet he had carried his unfair burden up through the Maine legislature to become governor of his state, and then congressman, senator, chairman and a power in national Republican councils. This had to bespeak the inner superiority that unkind fate can nurture - the compensating enlargement of brains, tenacity, guile, fortitude. On the hard testing ground of numberless speaking halls, committee chambers and smoke-filled rooms, he had somehow managed to warm the chill his visage cast, to triumph over his physiognomy through the qualities he brought to the lectern and the conference table.