Order of the White Feather

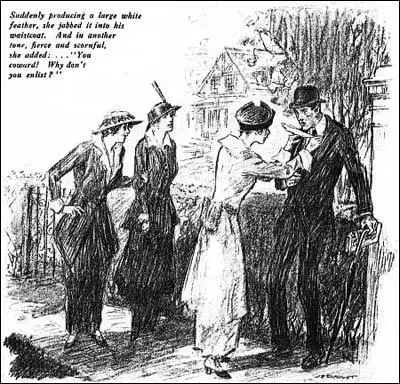

In August 1914, Admiral Charles Penrose Fitzgerald founded the Order of the White Feather. (1) He deputized thirty women in Folkestone to give out white feathers to any men not in uniform. The concept was based on the old cock-fighting lore that a cockerel with a white feather in its tail is a coward. (2)

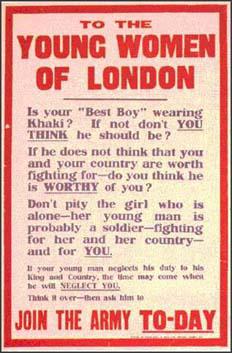

With the support of leading writers such as Mary Ward and Emma Orczy, the organisation encouraged women to give out white feathers to young men who had not joined the armed forces. Lord Kitchener gave his support to the campaign: "The women could play a great part in the emergency by using their influence with their husbands and sons to take their proper share in the country's defence, and every girl who had a sweetheart should tell men that she would not walk out with him again until he had done his part in licking the Germans." (3)

The Daily Mail enthusiastically reported the activities of the Order of the White Feather, hoping the gesture "would shame every young slacker" into enlisting. "The generally female white feather distributors achieved much notoriety by frequently misjudging their targets, stories of men on leave, wounded, or in reserved occupations being handed down these odious symbols abound." (4)

One young woman remembers her father, Robert Smith, being given a feather on his way home from work: "That night he came home and cried his heart out. My father was no coward, but had been reluctant to leave his family. He was thirty-four and my mother, who had two young children, had been suffering from a serious illness. Soon after this incident my father joined the army." Frederick Broome was only fifteen years of age, when he "accosted by four girls who gave me three white feathers." (5)

The government became concerned when women began presenting state employees with white feathers. It was suggested to Reginald McKenna, the Home Secretary, that these women should be arrested for "conduct likely to disrupt the police". McKenna refused but he did arrange for state employees to be issued with badges testifying that they were serving "King and Country".

Although he was a serving soldier, the writer, Compton Mackenzie, complained about the activities of the Order of the White Feather. He argued that these "idiotic young women were using white feathers to get rid of boyfriends of whom they were tired". The pacifist, Fenner Brockway, claimed that he received so many white feathers he had enough to make a fan. (6)

Another man was given a white feather on the same day he had been presented with the Victoria Cross at Buckingham Palace. (7) However, Lucy Noakes has defended these women by explaining that their actions were "more expressive of the desire amongst many women to be doing something, anything to help the war effort, rather than as evidence of a widespread jingoism amongst the female population." (8)

James Lovegrove, was only sixteen when he received his first white feather: "On my way to work one morning a group of women surrounded me. They started shouting and yelling at me, calling me all sorts of names for not being a soldier! Do you know what they did? They struck a white feather in my coat, meaning I was a coward. Oh, I did feel dreadful, so ashamed." He went to the recruiting office and at first he was rejected for being too young and too small: "You see, I was five foot six inches and only about eight and a half stone. This time he made me out to be about six feet tall and twelve stone, at least, that is what he wrote down. All lies of course - but I was in!".

Private Harold Carter was on leave from the Western Front. "On the Saturday I went to a music hall in civilian clothes and as I lined up outside a lady came along and put a white feather into my hand. I looked at it and felt disgusted, but there wasn't much I could do about it. I felt small enough over the white feather incident outside, but as I went into the gallery a chap came out in naval uniform and said that no girl should be sitting with a chap unless he was in uniform." (9)

William Brooks was also given a white feather at the age of sixteen. "Once war broke out the situation at home became awful, because people did not like to see men or lads of army age walking about in civilian clothing, or not in uniform of some sort, especially in a military town like Woolwich. Women were the worst. They would come up to you in the street and give you a white feather, or stick it in the lapel of your coat. A white feather is the sign of cowardice, so they meant you were a coward and that you should be in the army doing your bit for king and country.... In 1915 at the age of seventeen I volunteered under the Lord Derby scheme. Now that was a thing where once you applied to join you were not called up at once, but were given a blue armband with a red crown to wear. This told people that you were waiting to be called up, and that kept you safe, or fairly safe, because if you were seen to be wearing it for too long the abuse in the street would soon start again."

James Cutmore had attempted to volunteer for the British Army in 1914 but was rejected because he was short-sighted. "But in 1916, as he walked home to south London from his office, a woman gave him a white feather.... He enlisted the next day. By that time, they cared nothing for short sight. They just wanted a body to stop a shell, which Rifleman James Cutmore duly did in February 1918, dying of his wounds on March 28. My mother was nine, and never got over it. In her last years, in the 1980s, her once fine brain so crippled by dementia that she could not remember the names of her children, she could still remember his dreadful, lingering, useless death. She could still talk of his last leave, when he was so shell-shocked he could hardly speak and my grandmother ironed his uniform every day in the vain hope of killing the lice." (10)

Primary Sources

(1) Personal Column of The Times (8th July, 1915)

Jack F.G. If you are not in khaki by the 20th I shall cut you dead. Ethel M.

(2) Town Crier in Deal in Kent (September, 1914).

Oyez! Oyez! The White Feather Brigade. Ladies wanted to present to young men of Deal who have no one dependent on them the Order of the White Feather for shirking their duty in not offering their services to uphold the Union Jack of Old England.

(3) The Bystander (September, 1914).

Men who put on uniform as a result of exhortation by squires, parsons, retired officers, employers, schoolmasters, leader-writers, politicians, cartoonists, poets, music-hall singers and women are not volunteers; they are conscripts. They have gone in because it would have been so infernally unpleasant to have stayed out.

(4) James Lovegrove was only sixteen when he joined the army on the outbreak of the First World War.

On my way to work one morning a group of women surrounded me. They started shouting and yelling at me, calling me all sorts of names for not being a soldier! Do you know what they did? They struck a white feather in my coat, meaning I was a coward. Oh, I did feel dreadful, so ashamed.

I went to the recruiting office. The sergeant there couldn't stop laughing at me, saying things like "Looking for your father, sonny?", and "Come back next year when the war's over!" Well, I must have looked so crestfallen that he said "Let's check your measurements again". You see, I was five foot six inches and only about eight and a half stone. This time he made me out to be about six feet tall and twelve stone, at least, that is what he wrote down. All lies of course - but I was in!"

(5) William Brooks was interviewed about his experiences during the First World War in 1993. He explained why he joined the British Army in 1915.

Once war broke out the situation at home became awful, because people did not like to see men or lads of army age walking about in civilian clothing, or not in uniform of some sort, especially in a military town like Woolwich. Women were the worst. They would come up to you in the street and give you a white feather, or stick it in the lapel of your coat. A white feather is the sign of cowardice, so they meant you were a coward and that you should be in the army doing your bit for king and country.

It got so bad it wasn't safe to go out. So in 1915 at the age of seventeen I volunteered under the Lord Derby scheme. Now that was a thing where once you applied to join you were not called up at once, but were given a blue armband with a red crown to wear. This told people that you were waiting to be called up, and that kept you safe, or fairly safe, because if you were seen to be wearing it for too long the abuse in the street would soon start again.

(6) Words of Harold Begbie's song Fall In that was written in 1914.

How will you fare, sonny, how will you fare

In the far-off winter night

When you sit by the fire in the old man's chair

And your neighbours talk of the fight?

Will you slink away, as it were from a blow,

Your old head shamed and bent?

Or say, 'I was not with the first to go,

But I went, thank God, I went'?

(7) Francis Beckett, The Guardian (17th May 2008)

The war's extraordinary vividness is because it left a whole generation deeply and irreparably damaged, and that generation is close enough for many of us to have known members of it - and because millions of people can still do what I have just done. After reading, in quick succession, these four books about the men who fought the war (not a course of action I recommend as the preliminary to a carefree weekend), I took out a box of flimsy, yellowing letters, and tried yet again to imagine what my grandfather went through.

He had three small daughters, which saved him from conscription, and his attempt to volunteer was turned down in 1914 because he was short-sighted. But in 1916, as he walked home to south London from his office, a woman gave him a white feather (an emblem of cowardice). He enlisted the next day. By that time, they cared nothing for short sight. They just wanted a body to stop a shell, which Rifleman James Cutmore duly did in February 1918, dying of his wounds on March 28.

My mother was nine, and never got over it. In her last years, in the 1980s, her once fine brain so crippled by dementia that she could not remember the names of her children, she could still remember his dreadful, lingering, useless death. She could still talk of his last leave, when he was so shell-shocked he could hardly speak and my grandmother ironed his uniform every day in the vain hope of killing the lice. She treasured his letters from the front, which I now have, as well as information about his brothers and brothers-in-law who also died.

She blamed the politicians. She blamed the generation that sent him to war. She was with Kipling: "If any question why we died, / Tell them, because our fathers lied." She was with Sassoon: "If I were fierce, and bald, and short of breath / I'd live with scarlet majors at the Base, / And speed glum heroes up the line to death... And when the war is done and youth stone dead / I'd toddle safely home and die - in bed."

But most of all, she blamed that unknown woman who gave him a white feather, and the thousands of brittle, self-righteous women all over the country who had done the same. And there were thousands of them, as Will Ellsworth-Jones makes clear in his fascinating and thoughtful account of a group of conscientious objectors, We Will Not Fight. After the war, Virginia Woolf suggested there were only 50 or 60 white feathers handed out, but this was nonsense - as Ellsworth-Jones's diligent research shows.

Some of his stories still have the power to make the reader angry. A 15-year-old boy lied about his age to get into the army in 1914. He was in the retreat from Mons, the battle of the Marne and the first battle of Ypres, before he caught a fever and was sent home. Walking across Putney Bridge, four girls gave him white feathers. "I explained to them that I had been in the army and been discharged, and I was still only 16. Several people had collected around the girls and there was giggling, and I felt most uncomfortable and awfully embarrassed and... very humiliated." He walked straight into the nearest recruiting office and rejoined the army.

Student Activities

Walter Tull: Britain's First Black Officer (Answer Commentary)

Football and the First World War (Answer Commentary)

Football on the Western Front (Answer Commentary)

Käthe Kollwitz: German Artist in the First World War (Answer Commentary)

American Artists and the First World War (Answer Commentary)