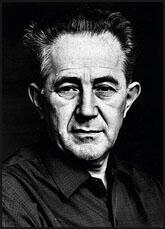

Milovan Djilas

Milovan Djilas was born in Montenegro, Yugoslavia, on 12th June, 1911. He became a member of the Yugoslav Communist Party while studying at Belgrade University in 1932 and was imprisoned for his political activities (1933-36). In 1938 Djilas was elected to the Central Committee of the Party and two years later a member of its Politburo.

The Yugoslavian government headed by Prince-Regent Paul allied itself with the fascist dictatorships of Germany and Italy. However, on 27th March 1941, a military coup established a government more sympathetic to the Allies. Ten days later the Luftwaffe bombed Yugoslavia and virtually destroyed Belgrade. The German Army invaded and the government was forced into exile.

Djilas joined his friend Josip Tito to help establish the partisan resistance fighters. Djilas was commander of the resistance forces in Montenegro and Bosnia during the war. In 1944 Tito sent Djilas to the Soviet Union where he had meetings with Joseph Stalin.

Initially the Allies provided military aid to the Chetniks led by Drazha Mihailovic. Information reached Winston Churchill that the Chetniks had began to collaborate with the Germans and Italians and at Teheran the decision was taken to switch this aid to Tito and the partisans.

In May 1944 a new government of Yugoslavia was established under Ivan Subasic. Tito was made War Minister in the new government. Djilas and his partisans continued their fight against the German Army and in October 1944 helped to liberate Belgrade.

In March 1945 Josip Tito became premier of Yugoslavia. Over the next few years he created a federation of socialist republics (Serbia, Croatia, Slovenia, Montenegro, Bosnia-Herzegovina and Macedonia). Djilas was vice president in Tito's government.

Tito had several disagreements with Joseph Stalin and in 1948 he sent Djilas as head of a Yugoslav delegation to meet Stalin in Moscow. Negotiations failed and later that year Tito took Yugoslavia out of the Comintern and pursued a policy of "positive neutralism". Influenced by the ideas of Djilas, Tito attempted to create a unique form of socialism that included profit sharing workers' councils that managed industrial enterprises.

Despite these reforms Djilas remained critical of how communism was developing in Yugoslavia and wrote about these issues in the Belgrade newspaper Borba and the political review, Nova Misao. In 1954 he was expelled from the party and lost all his government posts.

In 1955 Djilas published The New Class: An Analysis of the Communist System. In his book Djilas argued that communism in Eastern Europe was not an egalitarian society that it claimed to be. Instead, he argued, the party had established privileges enjoyed by a small group of party members (the New Class). Djilas was arrested in November 1956 and charged with "slandering and writing opinions hostile to the people and the state of Yugoslavia." Djilas was eventually sentenced to nine years in prison.

Soon after his release in 1961 he published Conversations with Stalin. This was based on his meetings with Joseph Stalin during the Second World War. This book led to a further period in prison (1962-66).

Djilas remained a committed socialist but argued that the dictatorship of the New Class inevitably carried within it the seeds of its own destruction. These views were expressed in books such as Under the Colours (1971), Land Without Justice (1972), Unperfect Society: Beyond the New Class (1972), Memoir of a Revolutionary (1973), Parts of a Lifetime (1975), Wartime: With Tito and the Partisans (1980), Tito: the Story from Inside (1981), Of Prisons and Ideas (1986) and Rise and Fall (1986).

After the death of Josip Tito in 1981 Djilas strongly opposed the break-up of Yugoslavia and the nationalist warfare that followed. He wrote: "Our system was built only for Tito to manage. Now that Tito is gone and our economic situation becomes critical, there will be a natural tendency for greater centralization of power. But this centralization will not succeed because it will run up against the ethnic-political power bases in the republics. This is not classical nationalism but a more dangerous, bureaucratic nationalism built on economic self-interest. This is how the Yugoslav system will begin to collapse."

Milovan Djilas died on 20th April 1997.

Primary Sources

(1) Milovan Djilas, Conversations With Stalin (1962)

He (Stalin) was of very small stature and ungainly build. His torso was short and narrow, while his legs and arms were too long. His left arm and shoulder seemed rather stiff. He had quite a large paunch, and his hair was sparse, though his scalp was not completely bald. His face was white, with ruddy cheeks. Later I learned that this coloration, so characteristic of those who sit long in offices, was known as the 'Kremlin complexion' in high Soviet circles. His teeth were black and irregular, turned inward. Not even his moustache was thick or firm. Still the head was not a bad one; it had something of the common people, the peasants, the father of a great family about it-with those yellow eyes and a mixture of sternness and mischief.

I was also surprised at his accent. One could tell that he was not a Russian. But his Russian vocabulary was rich, and his

manner of expression very vivid and flexible, and full of Russian proverbs and sayings. As I realized later, Stalin was

well acquainted with Russian literature - though only Russian - but the only real knowledge he had outside Russian limits was his knowledge of political history.

One thing did not surprise me: Stalin had a sense of humour - a rough humour, self-assured, but not entirely without subtlety and depth. His reactions, were quick and acute - and conclusive, which did not mean that he did not hear the speaker out, but it was evident that he was no friend of long explanations. Also remarkable was his relation to Molotov. He obviously regarded him as a very close associate, as I later confirmed. Molotov was the only member of the Politburo whom Stalin addressed with the familiar pronoun ty, which is in itself significant when one remembers that Russians normally use the polite form vy even among very close friends.

Stalin ate food in quantities that would have been enormous even for a much larger man. He usually chose meat, which was a sign of his mountain origins. He also liked all kinds of local specialities in which this land of various climes and civilizations abounded, but I did not notice that any one dish was his particular favourite. He drank moderately, usually mixing red wine and vodka in little glasses. I never noticed any signs of drunkenness in him, whereas I could not say the same for Molotov, let alone for Beria, who was practically a drunkard.

(2) Milovan Djilas met Joseph Stalin for the second time in 1945. In his book Rise and Fall he described the changes that had taken place in the man (1985)

In the three years since I had last seen him, in March 1945, Stalin had grown flabby and old. He had always eaten a lot, but now he was positively gluttonous, as if afraid someone might snatch the food from under his nose. He drank less, though, and with more caution. It was as if his energy and power were of use to no one now that the war had ended. In one thing, though, he was still the Stalin of old: he was crude and suspicious whenever anyone disagreed with him.

(3) Milovan Djilas, speech (1st May, 1951)

The further consolidation and extension of the personal rights of citizens, the further involvement of the broad masses in administering the state and the economy, the further development of brotherhood and unity among all our peoples, the further struggle against bureaucratic tendencies and all instances of the violation of our socialist legality - these are the tasks that confront our national groups our party, the People's Front, and social organizations.

And so our country raises high the banner of democracy and of socialism - a banner that today's rulers of the Soviet Union have trampled upon after depriving the working masses of all rights and freedoms, and adopting a policy of spheres of interest, of wars of conquest, of subjugating other peoples. All this they do to feed the exploitative, insatiable appetites of a bureaucratic caste that assumes the right - allegedly in the name of the struggle against capitalism - to plunder and squander the work of laborers in its "own" country and the countries of others.

(4) Milovan Djilas, speech on the decision to bring an end to compulsory physical labour for young people (March, 1953)

Mass youth labor action was necessary and heroic, but it can no longer be justified economically or politically. As we continue to strive for socialist education, let me point out that we should beware of dogmatism and fixed forms. ... In a country where socialism has triumphed ... a socialist education is not just the study of pure socialist theory, pure socialist principles; it is cultural achievement, it is raising the level of general education, it is attainment of literacy. Our country, our peoples, and especially our young are in a position where everything that moves man ahead and in any way lifts his cultural level constitutes socialist education.

(5) Milovan Djilas, Anti-Semitism (December, 1952)

Anti-Semitism besmirches and consumes all that is human in man and all that is democratic in a people. The historic stigma of shame that it imprints can never be wiped out. The violence of anti-Semitism is the measure by which a reactionary regime succeeds in enslaving its own people. But by the same token anti-Semitism marks the beginning of the end for those who make use of it, even if their powers are still on the rise.

(6) Josip Tito, speech on the articles by Milovan Djilas (29th November, 1951)

Regardless of whether or not such articles are basically accurate, none of us can always give a one-hundred-percent correct assessment and analysis before grasping the causes of certain phenomena, and before those causes have had a chance to filter down into the consciousness of the majority. Theoretical articles should not be discussed at party cell meetings as something prescribed and definitive; accordingly, party members should feel free to talk them over - not as the party line, not as something given and axiomatic, but as material that must make its impact on the mass development of theoretical thought... Accordingly, it is a mistake to confuse free discussion about questions of theory within a party organization with decisions already adopted on individual issues... In such discussions we dare not, we cannot judge people or make hasty decisions. Therefore, before bringing in a definitive judgment, it is quite correct to have discussions along democratic lines. Disciplined acceptance of a position taken by the majority on individual issues can come later.

(7) Milovan Djilas, Rise and Fall (1985)

After two or three days I was asked to come to the White Palace where I found Kardelj and Rankovic waiting with Tito. As I sat down, I asked for coffee, complaining of lack of sleep. As Tito got up to order it, he snapped at me. We aren t sleeping either." At one point I said to him "You I can understand. You've accomplished a lot and so you're protecting it. I've begun something and am defending it. But I wonder at these two (I meant Kardelj and Rankovic). Why are they so stubborn?"

Tito remarked that there seemed to be no movement organized around me, as indeed there was not. My only intention, I said was to develop socialism further. Tito's rebuttal consisted of trying to point out that the "reaction' - the bourgeoisie-was very strong still in our country and that all sorts of critics could hardly wait to attack us. As an example he cited Socrates, a satire, Just published, by Branko Copic, in which voters elect a dog by the name of Socrates, quite unconcerned with the object of their choice because they are convinced that this has been mandated "from on high." I maintained that topic's satire was an innocent joke, but no one agreed. Kardelj added that a few days earlier the funeral of a politician from the old regime - I forget who - had been attended by several hundred citizens! Rankovic sat the whole time in somber silence. His only comment, when my resignation as president of the National Assembly came up, was

that I ought to see to that myself, so that it wouldn't look as if it had been extracted under pressure or by administrative

methods. Finally Tito asked me to submit my resignation, adding decisively, "What must be, must be." As we said good-by he held out his hand, but with a look of hatred and vindictiveness.

As soon as I returned home, I wrote out my resignation, in bitterness. At the same time I asked my driver, Tomo, to deliver my cars to the White Palace. I had two - a Mercedes and a Jeep, which I used in isolated areas. Two days later Luka Leskosek, my escort, came looking for the suitcases that belonged to the Mercedes. In my haste I had forgotten them, and now I felt awkward because my initials had been engraved on them.

In the course of our conversation, Tito had remarked that my "case" was having the greatest world repercussion since our confrontation with the Soviet Union. I had replied that I didn't read the reports from Tanjug any more; they were no longer sent to me. "Get hold of them and see for yourself," Tito had said. That same day I went to Tanjug to look over the foreign press reports regarding my case. Reluctantly the news agency people obliged me. The volume and variety of reports had a twofold effect: I was impressed and encouraged but at the same time embarrassed and bothered that Western "capitalist" propaganda was so obviously biased in my favor.

(8) Milovan Djilas, Rise and Fall (1985)

Even the most fearful dream gets forgotten, but this was no dream. The Third Plenum was reality, a vain and shameful reality for all who took part. My main accusers, Tito and Kardelj, though seemingly concerned for party unity, were in fact concerned for their own prestige and power. To innate the peril, they fabricated guilt. After they had had their say, it was the turn of the tough, sharp-sighted powermongers - among them Minic and Stambolic, Pucar and Mannko, Blazo Jovanovic and Maslaric; then came the party weaklings, like Colakovic, and the hysterically penitent "self-critics," like Vukmanovic, Dapcevic, Vlahovic, Crvenkovski, and even Pijade - yes, Pijade, too, who until the day the plenum was scheduled had been sweetly smacking his lips over my articles. It could all have been foreseen. I had foreseen it. But reality is always different, either better or worse. This reality was more horrible, more shameless.

I was more prepared intellectually than emotionally for that plenum and its verdict, sure that I was in the right, yet sentimentally tied to my comrades. But that, too, is an oversimplification; the inner reality was more complex. My aloofness, my indifference to functions and honors - to power itself - helped account for my intellectual readiness, the ripeness of my understanding. What is more, having often in the previous months felt altogether sick of power, I had been relinquishing functions and plunging into reading and writing.

I knew at the time the importance of power, especially for carrying out political ideas, and know it even more clearly today. But at the time, I was repelled by that power, which was more an end in itself than the means to an end, and my disgust grew in proportion as I gazed into its "unsocialist," undemocratic nature. I couldn't say which came first, disgust or insight; they seemed mutually complementary and interchangeable. Even before the plenum was scheduled, I wanted to be "an ordinary person," I wanted to withdraw from power into intellectual and moral independence. Obviously I was deluding myself. This was only in part because the top leadership of a totalitarian party is incapable of releasing a member from its ranks except for "betrayal." My delusion owed just as much to my own intransigence, to my perceptions, which continued to mature, and to my sense of moral obligation to make them known.

The Third Plenum was held in the Central Committee building, which gave it an all-party character. (All plenary sessions of the Central Committee had previously been held at Tito's, in the White Palace.) The proceedings were also carried by radio, to give them a public and national character. I walked there with Stefica by my side; Dedijer accompanied us part of the way.

I arrived feeling numb, bodiless. A heretic, beyond doubt. One who was to be burned at the stake by yesterday's closest comrades,veterans who had fought decisive, momentous battles together. In the conference hall no one showed me to a seat, so I found a place for myself off at one corner of a square table. Nor did anyone exchange so much as a word with me, except when officially required to do so. To pass the time and record the facts, I took notes of the speeches. These I burned once the verbatim notes from the plenum were published.

Though I knew that the verdict had already been reached, I had no way of knowing the nature or severity of my punishment. Secretly, I hoped that, even while repudiating and dissociating itself from my opinions, the Central Committee would not expel me from the party, perhaps not even from the plenum. But all my democratic and comradely hopes were dashed once the contest was joined. Tito's speech was a piece of bitingly intolerant demogoguery. The reckoning it defined and articulated was not with an adversary who had simply gone astray or been disloyal in their eyes, but with one who had betrayed principle itself.

As Tito was speaking, the respect and fondness I had once felt for him turned to alienation and repulsion. That corpulent, carefully uniformed body with its pudgy, shaven neck filled me with disgust. I saw Kardelj as a petty and inconsistent man who disparaged ideas that till yesterday had been his as well, who employed antirevisionist tirades dating from the turn of the century, and who quoted alleged anti-Tito and anti-party remarks of mine from private conversations and out of context.

But I hated no one, not even these two, whose ideological and political rationalizations were so resolute, so bigoted, that the rest of my self-styled critics took their cue to be rabidly abusive - the Titoists aggressively and the penitents hysterically. Instead of requiting them with hatred and fury of my own, I withdrew into empty desolation behind my moral defenses.

The longer the plenum went on with its monotonous drumbeat of dogma, hatred, and resentment, the more conscious I became of the utter lack of open-minded, principled argument. It was a Stalinist show trial pure and simple. Bloodless it may have been, but no less Stalinist in every other dimension - intellectual, moral, and political.

(9) Milovan Djilas, Conversations With Stalin (1962)

Today I have come to the opinion that the deification of Stalin, or the 'cult of the personality', as it is now called, was at least as much the work of Stalin's circle and the bureaucracy, who required such a leader, as it was his own doing. Of course, the relationship changed. Turned into a deity, Stalin became so powerful that in time he ceased to pay attention to the changing needs and desires of those who exalted him.

An ungainly dwarf of a man passed through gilded and marbled imperial halls, and a path opened before him; radiant, admiring glances followed him, while the ears of courtiers strained to catch his every word. And he, sure of himself and his works, obviously paid no attention to all this. His country was in ruins, hungry, exhausted. But his armies and marshals, heavy with fat and medals and drunk with vodka and victory, had already trampled half of Europe under foot, and he was convinced they would trample over the other half in the next round. He knew that he was one of the cruellest, most despotic figures in human history. But this did not worry him a bit, for he was convinced that he was carrying out the will of history.

His conscience was troubled by nothing, despite the millions who had been destroyed in his name and by his order, despite the thousands of his closest collaborators whom he had murdered as traitors because they doubted that he was leading the country and people into happiness, equality, and liberty. The struggle had been dangerous, long, and all the more under-handed because the opponents were few in number and weak.

(10) Milovan Djilas, Conversations With Stalin (1962)

Until I visited Leningrad I could not have believed that anyone could have shown more heroism and sacrifice than the Partisans in Yugoslavia and the people, who lived in their territory. But Leningrad surpassed the Yugoslav revolution, if not in heroism then certainly in collective sacrifice. In that city of millions, cut off from the rear, without fuel or food, under the constant pounding of heavy artillery and bombs, about three hundred thousand people died of hunger and cold during the winter of 1941-2. Men were reduced to cannibalism, but there was no thought of surrender. Yet that is only the general picture. Not until we came into contact with the realities - with particular cases of sacrifice and heroism and with the living men who had been involved or had witnessed them - did we feel the grandeur of the epic of Leningrad and the strength that human beings-the Russian people-are capable of when the foundations of their spiritual and political existence and their way of life are threatened.

(11) Milovan Djilas, interview with Robert Kaplan (1981)

Our system was built only for Tito to manage. Now that Tito is gone and our economic situation becomes critical, there will be a natural tendency for greater centralization of power. But this centralization will not succeed because it will run up against the ethnic-political power bases in the republics. This is not classical nationalism but a more dangerous, bureaucratic nationalism built on economic self-interest. This is how the Yugoslav system will begin to collapse.

(12) Milovan Djilas, New Leader (19th November, 1956)

The experience of Yugoslavia appears to testify that national Communism is incapable of transcending the boundaries of Communism as such, that is, to institute the kind of reforms that would gradually transform and lead Communism to freedom. That experience seems to indicate that national Communism can merely break from Moscow and, in its own national tempo and way, construct essentially the identical Communist system. Nothing would be more erroneous, however, than to consider these experiences of Yugoslavia applicable to all countries of Eastern Europe.

The resistance of the leaders encouraged and stimulated the resistance of the masses. In Yugoslavia, therefore, the entire process was led and carefully controlled from above, and tendencies to go farther - to democracy - were relatively weak. If its revolutionary past was an asset to Yugoslavia while she was fighting for independence from Moscow, it became an obstacle as soon as it became necessary to move forward - to political freedom.

Yugoslavia supported this discontent as long as it was conducted by the Communist leaders, but turned against it - as in Hungary - as soon as it went further. Therefore, Yugoslavia abstained in the United Nations Security Council on the question of Soviet intervention in Hungary. This revealed that Yugoslav national Communism was unable in its foreign policy to depart from its narrow ideological and bureaucratic class interests, and that, furthermore, it was ready to yield even those principles of equality and non-interference in internal affairs on which all its successes in the struggle with Moscow had been based.

The Communist regimes of the East European countries must either begin to break away from Moscow, or else they will become even more dependent. None of the countries - not even Yugoslavia - will be able to avert this choice. In no case can the mass movement be halted, whether if follows the Yugoslav-Polish pattern, that of Hungary, or some new pattern which combines the two.

Despite the Soviet repression in Hungary, Moscow can only slow down the processes of change; it cannot stop them in the long run. The crisis is not only between the USSR and ifs neighbors, but within the Communist.

(13) David Pryce-Jones, Remembering Milovan Djilas (1999)

Still in prison, implacably defiant, Djilas smuggled out the manuscript of his next book, Conversations With Stalin, an account of his wartime missions to the Kremlin. Published in 1962, this made even more of a sensation. Such famous men as Churchill had penned memorable portraits of Stalin, but they were adversaries, even if reluctant admiration crept in. Djilas, in contrast, had been a true believer in Stalin, awed and excited to go on pilgrimage to someone he had visualized more as a deity than as a man. The observations have the immediacy of a thriller, acknowledging Stalin’s intelligence, his directness and rough humor, the underlying passion and irrationality. Those yellow eyes of his were like a tiger’s, pinpointing every minute shift of expression in others. But the vulgarity and blatancy of the man in private encounters, and especially at mealtimes among his henchmen, generated a terror all the more terrifying because so much remained unspoken. Here was eyewitness testimony which has certainly molded the portrait of Stalin for posterity.

(14) Robert Kaplan, Balkan Ghosts (1993)

By 1985, that reformer had emerged: Gorbachev. But Djilas was, by then, no longer impressed. "You will see that Gorbachev is also a figure of transition. He will make important reforms and introduce some degree of a market economy, but then the real crisis in the system will become apparent and the alienation in Eastern Europe will get much worse."

"What about Yugoslavia?" I asked.

He smiled viciously: "Like Lebanon. Wait and see."

In early 1989, Europe, if not America, was finally beginning to worry about Yugoslavia, and particularly about the new hard-liner in Serbia, Slobodan Milosevic. But the worry was only slight. There was still several months before the first East German refugees began streaming into Hungary on their way to the West, which eventually ignited a chain of events resulting in the collapse of Communist regimes across Eastern Europe. Eastern Europe was then enjoying its final months of anonymity in the world media.

But Djilas' mind was already in the 1990s:

"Milosevic's authoritarianism in Serbia is provoking real separation. Remember what Hegel said, that history repeats itself as tragedy and farce. What I mean to say is that when Yugoslavia disintegrates this time around, the outside world will not intervene as it did in 1914... Yugoslavia is the laboratory of all Communism. Its disintegration will foretell the disintegration in the Soviet Union. We are farther along than the Soviets."