On this day on 7th April

On this day in 1770 William Wordsworth was William Wordsworth, the son of an attorney, was born on 7th April 1770. After the death of his mother in 1778 and his father in 1783, Wordsworth was sent away to be educated at Hawkshead Grammar School in the Lake District. Wordsworth went to St. John's College, Cambridge where he developed radical political views. Influenced by the ideas of William Godwin, Wordsworth was an early supporter of the French Revolution.

Wordsworth went on a walking tour of France in 1790 and returned the following year and had an affair with Annette Vallon, the result of which was an illegitimate daughter, Ann Caroline. After the outbreak of war with France in 1793, Wordsworth returned to England. The poem, Guilt and Sorrow reveals that he still held strong views on social justice. He also wrote, Letter to the Bishop of Llandaff (1793), a pamphlet that gave support to the French Revolution. However, after the Reign of Terror (September 1793-July 1794), Wordsworth became disillusioned with radicalism. This was reflected in his verse drama, The Borderers (1796).

In 1796 Wordsworth set up home at Alfoxden in Somerset with his sister, Dorothy Wordsworth. His friend, Samuel Coleridge, who had also renounced his early revolutionary beliefs, lived three miles away at Nether Stowey. In 1798 they published the book Lyrical Ballads, which achieved a revolution in literary taste and sensibility. Lyrical Ballads included Wordsworth's Tintern Abbey and Coleridge's famous poems, the Ancient Mariner and The Nightingale.

In 1799 Dorothy and William moved to Grasmere in the Lake District. Three years later William Wordsworth married Mary Hutchinson. Over the next five years Wordsworth suffering several distressing experiences, including the death of two of his children, his brother being drowned at sea and Dorothy's mental breakdown. During this period Wordsworth worked on two major poems, The Recluse, which was never finished, and The Prelude, a poem that remained unpublished until after his death.

Wordsworth published Poems in Two Volumes in 1807. This including the poems: Ode to Duty (about the death of his brother), Resolution and Independence and Intimations of Immortality. Although attacked by William Hazlitt, Lord Byron and Percy Bysshe Shelley, for renouncing his early radicalism, Wordsworth was popular with most critics. The Excursion (1814) was well received and this was followed by The White Doe of Rylstone (1815), Miscellaneous Poems (1815) and The Waggoner (1819).

Wordsworth, now established as a conservative and patriotic poet, succeeded Robert Southey as poet laureate in 1843. William Wordsworth died at Rydal Mount, Ambleside on 23rd April 1850.

On this day in 1836 the philosopher, William Godwin, died. Godwin was born at Wisbech on 3rd March 1756. After three years at day school and three years with a private tutor in Norwich, Godwin entered Hoxton Presbyterian College. Godwin left college as a Tory but after five years as a minister he had developed radical political views. While he was a minister in Beaconsfield William Godwin became friendly with the Rational Dissenters, Richard Price and Joseph Priestley.

In 1787 Godwin left the ministry and became a full-time writer. Inspired by the writings of Tom Paine, Godwin published Enquiry into Political Justice in 1793. In the book Godwin argued that as long as people acted rationally, they could live without laws or institutions. The following year Godwin's pioneering novel, The Adventures of Caleb Williams, was published.

In 1797 Godwin married Mary Wollstonecraft but she died soon after their daughter was born. The following year he wrote Memoirs of the Author of a Vindication of the Rights of Women (1798). He also spent several years on the Life of Chaucer (1804).

Godwin's political ideas had a great influence on writers such as Percy Bysshe Shelley and Lord Byron. Godwin and Shelley became close friends. However, their relationship was damaged when in 1814, Shelley fell in love and eloped with Mary, Godwin's sixteen-year-old daughter. In later life Godwin concentrated on writing novels, the most popular being Mandeville (1817), Cloudesley (1830) and Deloraine (1833).

On this day in 1870 Gustav Landauer, the son of Hermann and Rosa Landauer, was born in Karlsruhe on 7th April, 1870. His parents owned a shoe store. He was an academic child who spent a lot of time on his own and sought refuge in "theatre, music, and especially books".

In 1888 Landauer entered the University of Heidelberg to study German and English literature, philosophy and art history. He also spent time in Strasbourg before settling in Berlin in 1892.

While at university he became an anarchist. In his autobiography he wrote: "I was an anarchist before I was a socialist, and one of the few who had not taken a detour via social democracy." He refused to join the fast growing Social Democratic Party (SDP). He later claimed: In the entire natural history I know of no more disgusting creature than the Social Democratic Party."

Landauer was deeply influenced by the work of Friedrich Nietzsche. In 1893 he published a novel, Preacher of Death, that was an expression of Nietzche's early liberation philosophy. He also worked with the New Free People's Theatre, a company committed to making educational and cultural projects accessible to workers.

In February 1893, Landauer and some of his friends established the journal Der Sozialist. In 1894 he was sentenced to almost a year in prison for libelous writing in the journal. In one essay, Anarchism in Germany, published in 1895, Landauer declared that "anarchism's lone objective is to end the fight of men against men and to unite humanity so that each individual can unfold his natural potential without obstruction." At this time a German police file called him "the most important agitator of the radical revolutionary movement."

Landauer was also involved in industrial disputes. In 1896 he became involved in a strike of textile workers in Berlin. During this period he became convinced that an "active general strike" could be used to create a revolutionary situation. Landauer was considered to be such a dangerous political figure that he was banned from German universities.

In February 1897 Landauer stood trial for libel after accusing a police inspector in Der Sozialist of recruiting informants from within left-wing organizations. Landauer was acquitted but two years later he was sent to prison for six months for claiming that the police had framed Albert Ziethen, a barber, for murdering his wife.

In the 1890s Landauer went on speaking tours and attended conferences in Zurich and London. During this period he met Peter Kropotkin, Rudolf Rocker, Louise Michel, Max Nettlau, Errico Malatesta and Élisée Reclus. Another contact during this period, Erich Mühsam, argued: "Landauer never saw anarchism as a politically or organizationally limited doctrine, but as an expression of ordered freedom in thought and action."

As Gabriel Kuhn has pointed out: "While he did not give up his anarchist and socialist leanings, he framed them in a new philosophical light. This was first characterized by an ever mounting discomfort with over-simplified class-analysis, doctrinism, and a light-hearted embrace of violence as a political means." Rudolf Rocker argued that Landauer's views distanced him from other anarchists: "page 40"

In 1903 Gustav Landauer divorced his first wife, Margarethe Leuschner, to marry poet Hedwig Lachmann, who had recently translated the works of Oscar Wilde and Walt Whitman into German. Over the next couple of years she gave birth to Gudula Susanne and Brigitte, the mother of future film director, Mike Nichols.

In 1907 Martin Buber arranged for the publication of Die Revolution. It has been described by Siegbert Wolf as a "seminal anarchist philosophy of history". However, others have criticised the work for dubious interpretations of past conflicts in history. One of his most important points is that the concept of "utopia" is the driving force behind all revolutionary action.

Landauer and Erich Mühsam established Sozialistischer Bund in May 1908, with the stated goal of "uniting all humans who are serious about realizing socialism". Landauer and Mühsam hoped to inspire the creation of small independent cooperatives and communes as the basic cells of a new socialist society. To support the new organisation, Landauer revived Der Sozialist, describing it as the Journal of the Socialist Bund.

One member of the group saw Mühsam as the "bohemian" and "activist" and Landauer as the "scholar" and "philosopher". Chris Hirte has argued that the made a good combination: "To sit in a chamber and to dream of anarchist settlements, as Landauer did, was not Mühsam's way. He had to be in the midst of life; he had to be where life was at its most colorful, where things fermented and brewed." Other important members included Martin Buber and Margarethe Faas-Hardegger. At its height, they had around 800 people associated with Sozialistischer Bund.

In an article published in Der Sozialist on 1st November 1910. Landauer argued: "The difference between us socialists in the Socialist Bund and the communists is not that we have a different model of a future society. The difference is that we do not have any model. we embrace the future's openness and refuse to determine it. What we want is to realize socialism, doing what we can for its realization now."

Landauer and Mühsam often argued about politics and morality. According to Gabriel Kuhn: "There were a few points of contention. The most important concerned matters of family life and sexuality. Landauer, who saw the nuclear family as the social core of mutual aid and solidarity, repeatedly drew the ire of Mühsam, who was a strong believer in free love and sexual experimentation. The conflict came to a head in 1910 over the publication of Landauer's article Tarnowska, a biting critique of free love, which Landauer saw as a mere pretext for moral and social degeneration. For a while, Mühsam even saw the friendship threatened, but the two soon managed to work out their differences."

Landauer was also in constant conflict with the German Anarchist Federation. This group was committed to class struggle as the central means for the revolution, whereas Landauer did not believe the working-class would ever be able to fulfil its proposed role of overthrowing capitalism. Such was his dislike of the organization that he refused to advertise its journal, Der Freie Arbeiter, in Der Sozialist.

Gustav Landauer also damaged his relationship with Margarethe Faas-Hardegger when he criticized her for an article questioning the nuclear family and arguing for communal child rearing. He admitted to Mühsam that "it has always been difficult for me to adopt and execute the ideas and plans for others". Mühsam pointed out: "Only those who see him as a determined and fearless fighter, kind, soft, and generous in everyday relations, but intolerant, hard, and head-strong to the point of arrogance in important issues, can understand him the way he really was."

Landauer was often in conflict with the followers of Karl Marx over the concept of revolution. He argued that a political revolution favoured by Marxists would never be enough. In an article, Who Shall Begin?, published in 1911, Landauer argued: "We believe that socialism has no bigger enemy than political power, and that it is socialism's task to establish a social and public order that replaces all such power." Landauer argued that for a real revolution to take place there had to be an "inner" change in the individual. As Mühsam pointed out: "Landauer's revolutionary activity was never limited to the fight against state laws and social systems. It concerned all dimensions of life."

Landauer and his wife, Hedwig Lachmann, were both pacifists and on the outbreak of the First World War they immediately became active in the anti-war movement. Erich Mühsam initially took a very different view. He wrote: "I am united with all Germans in the wish that we can keep foreign hordes away from our women and children, away from our towns and fields." Most of those on the left disagreed with Landauer and Lachmann on this issue. Siegbert Wolf has argued: "Hedwig Lachmann and Gustav Landauer were barely able to make their anti-militaristic stance comprehensive to friends and acquaintances."

In 1915 Landauer joined the New Fatherland Federation. Other members included Albert Einstein and Kurt Eisner. According to Landauer's biographer, Gabriel Kuhn: "Landauer entered a new phase of disappointment and loneliness. This, however, did not stop him from tireless anti-militaristic agitation. The anti-war and anti-nationalism pieces published during this period are ardent warnings against senseless brutality and slaughter, and passionate pleas for the unity of humanity, rather than its division."

On 28th October, Admiral Franz von Hipper and Admiral Reinhardt Scheer, planned to dispatch the fleet for a last battle against the British Navy in the English Channel. Navy soldiers based in Wilhelmshaven, refused to board their ships. The next day the rebellion spread to Kiel when sailors refused to obey orders. The sailors in the German Navy mutinied and set up councils based on the soviets in Russia. By 6th November the revolution had spread to the Western Front and all major cities and ports in Germany.

On 7th November, 1918, Kurt Eisner, leader of the Independent Socialist Party, declared Bavaria a Socialist Republic. Eisner made it clear that this revolution was different from the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia and announced that all private property would be protected by the new government. The King of Bavaria, Ludwig III, decided to abdicate and Bavaria was declared a Council Republic. Eisner's program was democracy, pacifism and anti-militarism.

Eisner, who got to know Landauer in the New Fatherland Federation, asked him to join his government in Munich. He wrote in a letter dated 14th November: "What I want from you is to advance the transformation of souls as a speaker." Others who arrived in the city to support the new regime included Erich Mühsam, Ernst Toller, Otto Neurath, Silvio Gesell and Ret Marut. Landauer became a member of several councils established to both implement and protect the revolution.

Eisner's government was defeated in the January 1919 election by the right-wing Bavarian People's Party. Eisner was on his way to present his resignation to the Bavarian parliament on 21st February, 1919, when he was assassinated in Munich by Anton Graf von Arco auf Valley. It is claimed that before he killed the leader of the government he said: "Eisner is a Bolshevist, a Jew; he isn't German, he doesn't feel German, he subverts all patriotic thoughts and feelings. He is a traitor to this land."

Eugen Levine, the leader of the German Communist Party (KPD) in Bavaria, fearing a counter-revolution, established a Bavarian Socialist Republic. Mühsam supported Levine's decision to establish the Soldiers' and Workers' Councils that took over the government from the National Assembly. Inspired by the events of the October Revolution, Levine ordered the expropriated of luxury flats and gave them to the homeless. Factories were to be run by joint councils of workers and owners and workers' control of industry and plans were made to abolish paper money. Levine, like the Bolsheviks had done in Russia, established Red Guard units to defend the revolution.

The Social Democratic Party government fled to the northern Bavarian town of Bamberg. A week later the SPD sent troops to Munich to overthrow Levine. During the fighting Erich Mühsam was captured and transported to Ebrach Prison. Landauer managed to avoid capture and on 16th April, 1919, he wrote to his daughter: "As far as I am concerned, I am all right staying here, although I am starting to feel rather useless."

Friedrich Ebert, the Chancellor of Germany, now ordered the German Army and the Freikorps into Bavaria. This force of roughly 39,000 men had little difficulty taking control of Munich. On 1st May, 1919, Gustav Landauer was captured. Rudolf Rocker explained what happened next: "Close friends had urged him to escape a few days earlier. Then it would have still been a fairly easy thing to do. But Landauer decided to stay. Together with other prisoners he was loaded on a truck and taken to the jail in Starnberg. From there he and some others were driven to Stadelheim a day later. On the way he was horribly mistreated by dehumanized military pawns on the orders of their superiors. One of them, Freiherr von Gagern, hit Landauer over the head with a whip handle. This was the signal to kill the defenseless victim.... He was literally kicked to death. When he still showed signs of life, one of the callous torturers shot a bullet in his head. This was the gruesome end of Gustav Landauer - one of Germany's greatest spirits and finest men."

On this day in 1877 Hubert von Herkomer publishes Westminster Union in The Graphic.Hubert von Herkomer was born in Germany on 26th May 1849. Hubert's family to England and in 1857 settled in Southampton. Herkomer studied at Southampton School of Art, the Munich Academy and the South Kensington Art School, where like his fellow student Luke Fildes, he was influenced by the work of Frederick Walker.

Herkomer left Kensington Art School and 1867 and started a career as a book and magazine illustrator. Herkomer found most of the work fairly boring but as a young man with radical political opinions he was excited by the news that the social reformer, William Luson Thomas, planned to publish an illustrated weekly magazine called the Graphic magazine.

Herkomer sent Thomas a drawing of a group of gypsies. Thomas accepted the picture and the following week it appeared in the Graphic. Herkomer was paid £8 for the picture and Thomas urged him to send more. Herkomer later recalled: "It is not too much to say that there was a visible change in the selection of subjects by painters in England after the advent of The Graphic. Mr. Thomas opened its pages to every phase of the story of our life; he led the rising artist into drawing subjects that might never have otherwise arrested his attention; he only asked that they should be subjects of universal interest and of artistic value."

Over the next few years Herkomer had a large number of his drawings published in the Graphic. However, unlike his two friends, Luke Fildes and Frank Holl, Herkomer was not offered a full-time post on the magazine. Where as staff members were commissioned, free-lance artists such as Herkomer had to find his own subject matter. Although Herkomer was angry when William Luson Thomas told him he was unwilling to employ him as a staff member of the Graphic, he later admitted: "In my heart I bitterly resented these words, but they were the words I needed: they were the making of me as an artist."

Several of Herkomer's engravings that appeared in the Graphic were later reworked as large-scale oil paintings. This included, The Last Muster (1875) and Eventide: A Scene in the Westminster Union (1878). The Last Muster had originally been used by the Graphic to show a group of old army veterans attending a church service. As a painting it was seven feet long and was sold to a photographic firm for £1,200.

In 1880s Hubert von Herkomer concentrated on the financially lucrative area of portraiture. He visited the USA and during a period of ten weeks received £6,600 for thirteen portraits. Herkomer's income was now higher than many of the rich people he painted and was now able to live a life of luxury. Although he received large sums of money for his portraits, Herkomer continued to produce social realist paintings. This included the Pressing to the West (1884), Hard Times (1885) and On Strike (1891).

Herkomer opened his own art school and during the period 1883 and 1904, trained over 500 students. Herkomer also served as Slade Professor of Art between 1885 and 1895.

Hubert von Herkomer, who was knighted in 1907, died ion 31st March 1914.

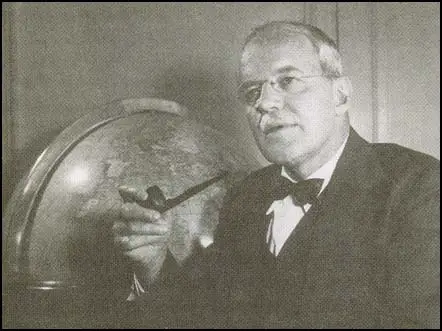

On this day in 1893 5th Director of CIA, Allen Dulles, the son of a Presbyterian minister, and the younger brother of John Foster Dulles, was born in Watertown. His grandfather was John Watson Foster, Secretary of State under Benjamin Harrison. His uncle, Robert Lansing, was Secretary of State in the Cabinet of President Woodrow Wilson.

After attending Princeton University he joined the diplomatic service and served in Vienna, Berne, Paris, Berlin and Instanbul. In 1921 he exposed the infamous Protocols of the Elders of Zion as a forgery, providing the story to The Times and The New York Times. In 1922 he was appointed as chief of Division of Near Eastern Affairs.

Dulles returned to the United States and in 1926 he obtained a law degree from George Washington University Law School and took a job at the New York City company, Sullivan and Cromwell, where his brother, John Foster Dulles, was a partner. He became a director of the Council on Foreign Relations in 1927 and became its secretary in 1933. He also served as an adviser to the delegation on arms limitation at the League of Nations. There he had the opportunity to meet with Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini.

In 1935 Dulles visited Nazi Germany. He was appalled by the treatment of German Jews and advocated his law firm to close their Berlin office. Dulles also joined forces with Hamilton Fish Armstrong to produce two books, Can We Be Neutral? (1936) and Can America Stay Neutral? (1939). Dulles was recruited by the British Security Coordination in 1940. In July 1941 Sydney Morrell was asked to write a report on the organisations that had been set up with the help of the BSC to call for intervention in the Second World War. It included reference to the help provided by Dulles.

The Office of Strategic Services (OSS) was created by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in July 1942. The OSS replaced the former American intelligence system, Office of the Coordinator of Information (OCI) that was considered to be ineffective. Roosevelt selected Colonel William Donovan as the first director of the organization, who had spent some time studying the Special Operations Executive (SOE), an organization set up by the British government in July 1940. Allen Dulles was recruited to run the New York City office. His address was Room 3603, 630 Fifth Avenue. The address of British Security Coordination was Room 3603, 630 Fifth Avenue.

Other key figures in the OSS was George K. Bowen, the head of Special Activities, David Bruce (head of intelligence) and William Lane Rehm (head of finance). Donald Chase Downes, who had been working for William Stephenson, the head of the British Security Coordination (BSC), applied to join the OSS. He later recalled in his autobiography, The Scarlett Thread (1953): "I was asked for references and for my life story and a week later was invited to Allen Dulles' new office. It was in Rockefeller Plaza, just a floor over the BSC secret office... At first Dulles and his aides were, quite justifiably, afraid of me - I had been an agent of a foreign power when that was prohibited by the Neutrality Act. So I was to work out of my own office in another part of New York."

Downes worked with Arthur Goldberg on the Labor Desk. "We were a fortunate combination, able to work together at high speed without friction. Our ideas, our plans, our points of view almost perfectly meshed; our abilities were peculiarly supplementary; our work so mutually understood and developed that each was able at any time to carry on or make a decision for the others." They recruited refugee German trade union leaders who had fled from Nazi Germany. Downes pointed out that Dulles believed in "an alliance between extreme right and extreme left" to remove Adolf Hitler from power.

Allen Dulles was transferred to Berne and became Swiss Director of the Office of Strategic Services. He used this neutral country to obtain important information on Nazi Germany. Dulles also developed contacts with anti-Hitler figures in Germany including Klaus von Stauffenberg, Arthur Nebe, Julius Leber, Kurt von Hammerstein-Equord, Helmuth von Moltke, Wilhelm Leuschner, Ulrich von Hassell, Ludwig Beck, Carl Friederich Goerdeler, and Wilhelm Leuschner. However, he was refused permission to give full support to the July Plot in 1944.

As soon as the Second World War ended President Harry S. Truman ordered the Office of Strategic Services to be closed down. However, it provided a model for the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) that was established in September 1947. Dulles joined the CIA and became deputy director of the organization.

After the war a small group of people began meeting on a regular basis. The group, living in Washington, became known as the Georgetown Set or the Wisner Gang. At the first the key members of the group were former members of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). This included Frank Wisner, Philip Graham, David Bruce, Tom Braden, Stewart Alsop and Walt Rostow. Over the next few years others like Allen Dulles, George Kennan, Dean Acheson, Richard Bissell, Joseph Alsop, Eugene Rostow, Chip Bohlen, Desmond FitzGerald, Tracy Barnes, Cord Meyer, James Angleton, William Averill Harriman, John McCloy, Felix Frankfurter, John Sherman Cooper, James Reston, and Paul Nitze joined their regular parties. Some like Bruce, Braden, Bohlen, McCloy, Meyer and Harriman spent a lot of their time working in other countries. However, they would always attend these parties when in Georgetown.

Tommy Corcoran worked as a paid lobbyist for Sam Zemurray and the United Fruit Company. Zemurray became concerned that Captain Jacobo Arbenz, one of the heroes of the 1944 revolution, would be elected as the new president of Guatemala. In the spring of 1950, Corcoran went to see Thomas C. Mann, the director of the State Department’s Office of Inter-American Affairs. Corcoran asked Mann if he had any plans to prevent Arbenz from being elected. Mann replied: “That is for the people of that country to decide.”

Unhappy with this reply, Corcoran paid a call on Allen Dulles, who represented United Fruit in the 1930s, was far more interested in Corcoran’s ideas. “During their meeting Dulles explained to Corcoran that while the CIA was sympathetic to United Fruit, he could not authorize any assistance without the support of the State Department. Dulles assured Corcoran, however, that whoever was elected as the next president of Guatemala would not be allowed to nationalize the operations of United Fruit.”

In 1954 Dulles, now director of the CIA organized PB/SUCCESS, a CIA operation to overthrow President Jacobo Arbenz. Other CIA officers involved in this operation included David Atlee Phillips, Tracy Barnes, William (Rip) Robertson and E. Howard Hunt. Hecksher's role was to supply front-line reports and to bribe Arbenz's military commanders. It was later discovered that one commander accepted $60,000 to surrender his troops. Ernesto Guevara attempted to organize some civil militias but senior army officers blocked the distribution of weapons.

With the help of President Anastasio Somoza, Colonel Carlos Castillo had formed a rebel army in Nicaragua. It has been estimated that between January and June, 1954, the CIA spent about $20 million on Castillo's army. Jacobo Arbenz now believed he stood little chance of preventing Castillo gaining power. Accepting that further resistance would only bring more deaths he announced his resignation.

According to David Atlee Phillips (Night Watch), President Dwight Eisenhower was so pleased with the overthrow of Jacobo Arbenz he invited Allen Dulles, Henry Hecksher, Tracy Barnes, David Sanchez Morales, and Allen Dulles to a personal debriefing at the White House.

In March 1960 Richard Bissell had drafted a top-secret policy paper entitled: A Program of Covert Action Against the Castro Regime (code-named JMARC). This paper was based on PBSUCCESS, the policy that had worked so well in Guatemala in 1954. In fact, Bissell assembled the same team as the one used in Guatemala (Tracy Barnes, David Atlee Phillips, David Morales, Jake Esterline, Rip Robertson, E. Howard Hunt and Gerry Droller “Frank Bender”). The only one missing was Frank Wisner, who had suffered a mental breakdown in 1956. Added to the team was Desmond FitzGerald, William Harvey and Ted Shackley.

The policy involved the creation of an exile government, a powerful propaganda offensive, developing a resistance group within Cuba and the establishment of a paramilitary force outside Cuba. In Guatemala this strategy involved persuading Jacobo Arbenz to resign. Richard Bissell knew of course that Fidel Castro would never agree to that. Therefore, Castro had to be removed just before the invasion took place. If this did not happen, the plan would not work. In August 1960 Dwight Eisenhower authorized $13m to pay for JMARC.

Sidney Gottlieb of the CIA Technical Services Division was asked to come up with proposals that would undermine Castro's popularity with the Cuban people. Plans included a scheme to spray a television studio in which he was about to appear with an hallucinogenic drug and contaminating his shoes with thallium which they believed would cause the hair in his beard to fall out.

These schemes were rejected and instead Bissell decided to arrange the assassination of Fidel Castro. In September 1960 Richard Bissell and Allen W. Dulles, the director of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), initiated talks with two leading figures of the Mafia, Johnny Roselli and Sam Giancana. Later, other crime bosses such as Carlos Marcello, Santos Trafficante and Meyer Lansky became involved in this plot against Castro.

Robert Maheu, a veteran of CIA counter-espionage activities, was instructed to offer the Mafia $150,000 to kill Fidel Castro. The advantage of employing the Mafia for this work is that it provided CIA with a credible cover story. The Mafia were known to be angry with Castro for closing down their profitable brothels and casinos in Cuba. If the assassins were killed or captured the media would accept that the Mafia were working on their own.

The Federal Bureau of Investigation had to be brought into this plan as part of the deal involved protection against investigations against the Mafia in the United States. Castro was later to complain that there were twenty ClA-sponsered attempts on his life. Eventually Johnny Roselli and his friends became convinced that the Cuban revolution could not be reversed by simply removing its leader. However, they continued to play along with this CIA plot in order to prevent them being prosecuted for criminal offences committed in the United States.

John F. Kennedy was given a copy of the JMARC proposal by Bissell and Allen W. Dulles in Palm Beach on 18th November, 1960. According to Bissell, Kennedy remained impassive throughout the meeting. He expressed surprise only at the scale of the operation. The plan involved a 750 man landing on a beach near the port of Trinidad, on the south coast of Cuba. The CIA claimed that Trinidad was a hotbed of opposition to Castro. It was predicted that within four days the invasion force would be able to recruit enough local volunteers to double in size. Airborne troops would secure the roads leading to the town and the rebels would join up with the guerrillas in the nearby Escambray Mountains.

In March 1961 John F. Kennedy asked the Joint Chiefs of Staff to vet the JMARC project. As a result of “plausible deniability” they were not given details of the plot to kill Castro. The JCS reported that if the invaders were given four days of air cover, if the people of Trinidad joined the rebellion and if they were able to join up with the guerrillas in the Escambray Mountains, the overall rating of success was 30%. Therefore, they could not recommend that Kennedy went along with the JMARC project.

At a meeting on 11th March, 1961, Kennedy rejected Bissell’s proposed scheme. He told him to go away and draft a new plan. He asked for it to be “less spectacular” and with a more remote landing site than Trinidad. It appears that Kennedy had completely misunderstood the report from the JCS. They had only rated it as high as a 30% chance of success because it was going to involve such a large landing force and was going to take place in Trinidad, near to the Escambray Mountains. After all, Fidel Castro had an army and militia of 200,000 men.

Richard Bissell now resubmitted his plan. As requested, the landing was no longer at Trinidad. Instead he selected Bahia de Cochinos (Bay of Pigs). This was 80 miles from the Escambray Mountains. What is more, this journey to the mountains was across an impenetrable swamp. As Bissell explained to Kennedy, this means that the guerrilla fallback option had been removed from the operation.

As Dulles recorded at the time: “We felt that when the chips were down, when the crisis arose in reality, any action required for success would be authorized rather than permit the enterprise to fail.” In other words, he knew that the initial invasion would be a disaster, but believed that Kennedy would order a full-scale invasion when he realized that this was the case. According to Evan Thomas (The Very Best Men): “Some old CIA hands believe that Bissell was setting a trap to force U.S. intervention”. Edgar Applewhite, a former deputy inspector general, believed that Bissell and Dulles were “building a tar baby”. Jake Esterline was very unhappy with these developments and on 8th April attempted to resign from the CIA. Bissell convinced him to stay.

On 10th April, 1961, Bissell had a meeting with Robert Kennedy. He told Kennedy that the new plan had a two out of three chance of success. Bissell added that even if the project failed the invasion force could join the guerrillas in the Escambray Mountains. Kennedy was convinced by this scheme and applied pressure on those like Chester Bowles, Theodore Sorenson and Arthur Schlesinger who were urging John F. Kennedy to abandon the project.

On 13th April, Kennedy asked Richard Bissell how many B-26s were going to be used. He replied sixteen. Kennedy told him to use only eight. Bissell knew that the invasion could not succeed without adequate air cover. Yet he accepted this decision based on the idea that he would later change his mind “when the chips were down”. The following day B-26 planes began bombing Cuba's airfields. After the raids Cuba was left with only eight planes and seven pilots. Two days later five merchant ships carrying 1,400 Cuban exiles arrived at the Bay of Pigs.

Allen W. Dulles was in Puerto Rico during the invasion. He left Charles Cabell in charge. Instead of ordering the second air raid he checked with Dean Rusk. He contacted Kennedy who said he did not remember being told about the second raid. After discussing it with Rusk he decided to cancel it. Instead the operation tried to rely on Radio Swan, broadcasts being made on a small island in the Caribbean by David Atlee Phillips, calling for the Cuban Army to revolt. They failed to do this. Instead they called out the militia to defend the fatherland from “American mercenaries”.

At 7 a.m. on 18th April, Richard Bissell told John F. Kennedythat the invasion force was trapped on the beaches and encircled by Castro’s forces. Then Bissell asked Kennedy to send in American forces to save the men. Bissell expected him to say yes. Instead he replied that he still wanted “minimum visibility”.

After the air raids Cuba was left with only eight planes and seven pilots. Two days later five merchant ships carrying 1,400 Cuban exiles arrived at the Bay of Pigs. Two of the ships were sunk, including the ship that was carrying most of the supplies. Two of the planes that were attempting to give air-cover were also shot down.

That night Bissell had another meeting with John F. Kennedy. This time it took place in the White House and included General Lyman Lemnitzer, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and Admiral Arleigh Burke, Chief of Naval Operations. Bissell told Kennedy that the operation could still be saved if American warplanes were allowed to fly cover. Admiral Burke supported him on this. General Lemnitzer called for the Brigade to join the guerrillas in the Escambray Mountains. Bissell explained this was not an option as their route was being blocked by 20,000 Cuban troops.

Within seventy-two hours all the invading troops had been killed, wounded or had surrendered. Bissell had a meeting with John F. Kennedy about the Bay of Pigs operation. Kennedy admitted it was his fault that the operation had been a disaster. Kennedy added: "In a parliamentary government, I'd have to resign. But in this government I can't, so you and Allen (Dulles) have to go."

As Evan Thomas points out in The Very Best Men: "Bissell had been caught in his own web. "Plausible deniability" was intended to protect the president, but as he had used it, it was a tool to gain and maintain control over an operation... Without plausible deniability, the Cuba project would have turned over to the Pentagon, and Bissell would have have become a supporting actor."

The CIA's internal inquiry into this fiasco and Allen W. Dulles was forced to resign as Director of the CIA (November, 1961) by President John F. Kennedy. After the death of Kennedy, his deputy, Lyndon B. Johnson, was appointed president. He immediately set up a commission to "ascertain, evaluate and report upon the facts relating to the assassination of the late President John F. Kennedy." The seven man commission was headed by Chief Justice Earl Warren and included Allen W. Dulles, Gerald Ford, John J. McCloy, Richard B. Russell, John S. Cooper and Thomas H. Boggs.

Lyndon B. Johnson also commissioned a report on the assassination from J. Edgar Hoover. Two weeks later the Federal Bureau of Investigation produced a 500 page report claiming that Lee Harvey Oswald was the sole assassin and that there was no evidence of a conspiracy. The report was then passed to the Warren Commission. Rather than conduct its own independent investigation, the commission relied almost entirely on the FBI report.

The Warren Commission was published in October, 1964. It reached the following conclusions:

(1) The shots which killed President Kennedy and wounded Governor Connally were fired from the sixth floor window at the southeast corner of the Texas School Book Depository.

(2) The weight of the evidence indicates that there were three shots fired.

(3) Although it is not necessary to any essential findings of the Commission to determine just which shot hit Governor Connally, there is very persuasive evidence from the experts to indicate that the same bullet which pierced the President's throat also caused Governor Connally's wounds. However, Governor Connally's testimony and certain other factors have given rise to some difference of opinion as to this probability but there is no question in the mind of any member of the Commission that all the shots which caused the President's and Governor Connally's wounds were fired from the sixth floor window of the Texas School Book Depository.

(4) The shots which killed President Kennedy and wounded Governor Connally were fired by Lee Harvey Oswald.

(5) Oswald killed Dallas Police Patrolman J. D. Tippit approximately 45 minutes after the assassination.

(6) Within 80 minutes of the assassination and 35 minutes of the Tippit killing Oswald resisted arrest at the theater by attempting to shoot another Dallas police officer.

(7) The Commission has found no evidence that either Lee Harvey Oswald or Jack Ruby was part of any conspiracy, domestic or foreign, to assassinate President Kennedy.

(8) In its entire investigation the Commission has found no evidence of conspiracy, subversion, or disloyalty to the U.S. Government by any Federal, State, or local official.

(9) On the basis of the evidence before the Commission it concludes that, Oswald acted alone.

Dulles published several books including The German Underground, The Craft of Intelligence and Great True Spy Stories.

Allen Dulles died of cancer on 29th January 1969.

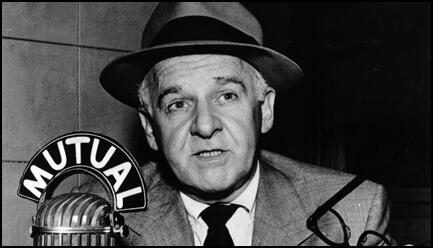

On this day in 1897 Walter Winchell was born in New York City. After leaving school he worked for a vaudeville troupe. It soon became clear that he was not going to be a success in this profession and in 1920 he found work as a journalist for Vaudeville News . Four years later he joined the Evening Graphic .

Winchell's career did not take off until he was recruited by the New York Daily Mirror in 1929, a newspaper owned by William Randolph Hearst. Winchell started a gossip column, entitled On-Broadway. Winchell used his connections to publish confidential information about people in the public eye. His work appeared in nearly 2,000 newspapers and he also did a Sunday radio broadcasts. Combined, they reached 50 million homes. His attorney, Ernest Cuneo, has argued that "when Walter finished broadcasting on Sunday night, he had reached 89 out of 100 adults in the U.S." Bernard Weinraub has pointed out: "From Table 50 at the Stork Club - he never picked up the tab - Winchell held court like a prince, beckoning prizefighters, movie stars, debutantes, royalty and gangsters to his table. He demanded to know what they were doing but talked most of the time himself." Jennet Conant has argued that "Winchell was a powerhouse widely feared because of his penchant for exposing the private lives of important public men - from mistresses and pregnancies to divorces - which gave him plenty of bargaining chips to trade for information about what was going on inside their businesses or agencies."

Ralph D. Gardner, a fellow journalist, has argued: "Feeding the public’s craving for scandal and gossip, he became the most powerful - and feared - journalist of his time.... The columns, written in his own style, were composed of short sentences connected by three dots. Fed by press agents, tipsters, legmen and ghost writers, he possessed the extraordinary ability to make a Broadway show a hit, create overnight celebrities; enhance or destroy a political career. The workaholic Winchell was first to announce big-name marriages and divorces, Hollywood romances, exploits of socialites, international playboys, debutantes, mobsters and chorus girls, plus latest reports of café society antics... He would also give timely plugs to show-biz unknowns or has-beens who were sorely in need of a helping hand. At the same time he savaged any whom he perceived to be his enemies." Winchell was a powerhouse widely feared because of his penchant for exposing the private lives of important public men - from mistresses and pregnancies to divorces - which gave him plenty of bargaining chips to trade for information about what was going on inside their businesses or agencies. The New York Times described Winchell as "the country’s best-known, widely read journalist as well as its most influential."

Winchell, who was Jewish, was one of the first journalists to condemn Adolf Hitler and isolationist groups such as the American First Committee. Winchell argued that "isolation ends where it always ends - with the enemy on our doorstep", and introduced a regular feature called "The Winchell Column vs. the Fifth Column." Later, Ernest Cuneo, who was working with the British Security Coordination (BSC), claimed: "FDR was at war with Hitler long before Chamberlain was forced to declare it. I was eyewitness and indeed, wrote Winchell's stuff on it."

Winchell was a staunch supporter of President Franklin Roosevelt and the New Deal throughout the 1930s. He also held strong views on civil rights and frequently attacked the Ku Klux Klan. The author of The Irregulars: Roald Dahl and the British Spy Ring in Wartime Washington (2008) has argued: "He had morphed from a Broadway critic to a political commentator who thought nothing of weighing in on domestic and international affairs... A typical Winchell column would contain several dozen separate references to individuals and events, ranging from minor celebrity sightings, along the lines of spotting Marlene Diettrich at the Stork Club, his nightly hangout, to an impassioned denunciation of Nazi sympathizers or some other disreputable homegrown fascists."

Benjamin de Forest Bayly has suggested that William Stephenson, who was head of BSC, was very close to Winchell: "He liked propaganda. And propaganda was really one of the important things he did. He saw to it, before even Pearl Harbor, that the anti-British feeling there was squelched by writers. He got all sorts of people to write things that helped that... Winchell was a man who actually got a reputation for being a very straightforward person, and he did a lot of propaganda work for Bill Stephenson. If Bill could sell him on why the U.S. should do this, and if it did that, then Winchell would be your man."

Winchell became a close friend of J. Edgar Hoover, the head of the FBI, in 1938. Curt Gentry, the author of J. Edgar Hoover: The Man and the Secrets (1991): "Unquestionably each used the other. It was Winchell, more than any other journalist, who sold the G-man image to America; while Hoover, according to Cuneo and others, supplied Winchell with inside information that led to some of his biggest scoops.... In addition to the tips, Hoover often supplied Winchell with an FBI driver when he was travelling; assigned FBI agents as bodyguards whenever the columnist received a death threat, which was often."

In early August 1939 Winchell received a message from a contact that suggested that Louis Lepke Buchalter was willing to surrender to the FBI if a deal was possible. Lepke was unwilling to surrender to New York's district attorney, Thomas Dewey, as he had vowed to execute him. Winchell now made a radio broadcast appealing to Lepke to give himself up: "Attention Public Enemy Number One, Louis 'Lepke' Buchalter! I am authorized by John Edgar Hoover of the Federal Bureau of Investigation to guarantee you safe delivery to the FBI if you surrender to me or to any agent of the FBI. I will repeat: Leapke, I am authorized by John Edgar Hoover."

On 24th August Walter Winchell received another message from Lepke. He phoned J. Edgar Hoover: "My friends, John, have instructed me to tell you to be at Twenty-eighth Street and Fifth Avenue between ten-ten and ten-twenty tonight. That's about half an hour. They told me to tell you to be alone." Curt Gentry explains that "Hoover was not on foot, and he wasn't alone. Unknown to Winchell, more than two dozen agents had the corner under surveillance. Having picked up Lepke several blocks away, per instructions, Winchell pulled up beside the director's distinctive black limousine. Then he and Lepke got into the back of the FBI vehicle." Winchell later recalled that Hoover was "disguised in dark glasses to keep him from being recognized by passersby".

Louis Lepke Buchalter was tried on federal charges and sentenced to fourteen years in Leavenworth (Hoover had promised him he'd get only ten years and that with good behaviour he'd be out in five or six). The Chicago Tribune published a story that the FBI and the Justice Department had made a deal with Lepke, to keep him from telling what he knew about the Roosevelt administration's links with Murder Incorporated. President Franklin Roosevelt was so angry about the accusation he ordered that Lepke should be handed over to Thomas Dewey. When Abe Reles agreed to provide evidence against Buchalter, he was tried for murder. Found guilty, Buchalter was executed at Sing Sing State Prison on 4th March, 1944.

After the Second World War Winchell became obsessed with the threat of communism. When Josephine Baker complained about the racial-discriminatory policies of the Stork Club in New York City he retaliated by calling her a communist and began a campaign which prevented her from getting her visa to enter the US renewed. He was criticised by fellow journalists, including Ed Sullivan, who said, ''I despise Walter Winchell because he symbolizes to me evil and treacherous things in the American setup.''

Winchell also gave his support to Joseph McCarthy. As Ralph D. Gardner has pointed out: "In the 1950’s Winchell’s direction took an odd turn that was distressing to millions of readers. He became a supporter of Sen. Joseph McCarthy, filling his pages and broadcasts with vindictive, denunciatory tirades and mean-spirited accusations that resulted in lawsuits and loss of media outlets. He had climbed to the top and tumbled." In 1963 New York Daily Mirror, a newspaper who he worked for 34 years, closed, his life as a columnist came to an end.

Walter Winchell died of prostate cancer on 20th February, 1972.

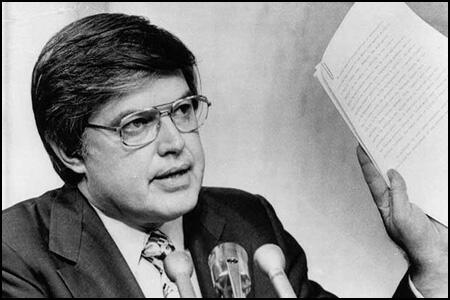

On this day in 1931 Daniel Ellsberg was born in Detroit. After graduating from Harvard in 1952 he studied at King's College, Cambridge.

Ellsberg joined the U.S. Marine Corps in 1954. Over the next three years he served as a rifle platoon leader, operations officer, and rifle company commander.

In 1957 Ellsberg became a Junior Fellow in the Society of Fellows, Harvard University. He earned his Ph.D. in Economics at Harvard with his thesis, Risk, Ambiguity and Decision. In 1959, he became a strategic analyst at the RAND Corporation, and consultant to the Department of Defense and the White House, specializing in problems of the command and control of nuclear weapons, nuclear war plans, and crisis decision-making.

Ellsberg joined the Defense Department in 1964 as Special Assistant to Assistant Secretary of Defense (International Security Affairs) John McNaughton, working on Vietnam. He transferred to the State Department in 1965 to serve two years at the US Embassy in Saigon, evaluating pacification on the front lines. He worked under Edward Lansdale. Ellsberg liked Lansdale because of his commitment to democracy.

Ellsberg also agreed with Lansdale that the pacification program should be run by the Vietnamese. He argued that unless it was a Vietnam project it would never work. Lansdale knew that there was a deep xenophobia among Vietnamese. However, as he pointed out, he believed "Lyndon Johnson would have been just as xenophobic if Canadians or British or the French moved in force into the United States and took charge of his dreams for a great Society, told him what to do, and spread out by thousands throughout the nation to see that it got done."

In 1967 Ellsberg became a member of the McNamara Study Group that in 1968 had produced the classified History of Decision Making in Vietnam, 1945-1968. Ellsberg, disillusioned with the progress of the war, believed this document should be made available to the public. He gave a copy of what later became known as the Pentagon Papers to William Fulbright. However, he refused to do anything with the document, so Ellsberg gave a copy to Phil Geyelin of the Washington Post. Katharine Graham and Ben Bradlee decided against publishing the contents on the document.

Ellsberg now went to the New York Times and they began publishing extracts from the document on 13th June, 1971. This included information that Dwight Eisenhower had made a secret commitment to help the French defeat the rebellion in Vietnam. The document also showed that Lyndon B. Johnson had turned this commitment into a war by using a secret "provocation strategy" that led to the Gulf of Tonkin incidents and that Johnson had planned from the beginning of his presidency to expand the war.

Ben Bradlee was criticised by his journalists for failing to break this story. He now made attempts to catch up and on June 18, 1971, the Washington Post began publishing extracts from the History of Decision Making in Vietnam, 1945-1968. However, Bradlee concentrated on the period when Dwight Eisenhower was in power. The first story reported on how the Eisenhower administration had delayed democratic elections in Vietnam.

Richard Nixon now made attempts to prevent anymore extracts from the Pentagon Papers being published. The Supreme Court ruled against Nixon and Hugo Black commented that the two newspapers "should be commended for serving the purpose that the Founding Fathers saw so clearly".

Ellsberg's trial, on twelve felony counts posing a possible sentence of 115 years, was dismissed in 1973 on grounds of governmental misconduct against him, which led to the convictions of several White House aides and figured in the impeachment proceedings against President Richard Nixon.

Since the end of the Vietnam War he has been a lecturer, writer and activist on the dangers of the nuclear era and unlawful interventions. In 2002 Daniel Ellsberg published Secrets.

On this day in 1933 Prohibition comes to an end in the United States. The prohibition movement in the United States began in the early 1800s and by 1850 several states had passed laws that restricted or prevented people drinking alcohol. Early campaigners for prohibition included William Lloyd Garrison, Frances E. Willard, Anna Howard Shaw, Carry Nation, Mary Lease and Ida Wise Smith.

Neal Dow, a prosperous businessman in Portland, Maine, established the Young Men's Abstinence Society. He also led the campaign that resulted in Maine passing the nation's first prohibition law in 1846.

During the 19th century, two powerful pressure groups, the Anti-Saloon League and the Women's Christian Temperance Union were established in America. In 1869 members of the temperance movement formed the Prohibition Party. Three years later James Black of Pennsylvania became the party's candidate for the presidency. However he won only 5,608 votes.

In 1879 John St. John was elected governor of Kansas. Four years later he succeeded in making Kansas the first state to outlaw alcohol by constitutional amendment. This action made him the hero of the temperance movement and in 1884 the Prohibition Party chose St. John as their presidential candidate.

St. John won only 150,369 votes in the election but it was a great improvement on previous candidates. He also took valuable votes from the Republican Party candidate, James Blaine, and helped Grover Cleveland of the Democratic Party to win victory. Cleveland was the first Democrat to become president since the Civil War. One newspaper described him as a "Judas Iscariot" and Republicans in over a hundred towns burned his effigy.

Other presidential candidates included Clinton Bowen Fisk (1888 - 249,506), John Bidwell (1892 - 264,133), Joshua Levering (1896 - 132,007), John Granville Woolley (1900 - 208,914), Silas Comfort Swallow (1904 -258,536), Eugene Wilder Chafin (1908 - 253,840 and 1912 - 206,275) and James Franklin Hanly (1916 - 220,506).

During the First World War most people considered it to be unpatriotic to use much needed grain to produce alcohol. Also, several of the large brewers and distillers were of German origin. Many business leaders believed their workers would be more productive if alcohol could be withheld with them. John D. Rockefeller, alone, donated over $350,000 to the Anti-Saloon League.

Opinion on prohibition began to change and by January, 1919, 75% of the states in America had approved the 18th Amendment which prohibited the "sale or transportation of intoxicating liquors". This became the law of the land when the Volstead Act was passed in 1920.

One of the consequences of the National Prohibition Act was the development of gangsterism and crime. Enforcement of prohibition was a difficult task and a growth in illegal drinking places took place. People called moonshiners distilled alcohol illegally. Bootleggers sold the alcohol and also imported it from abroad. The increase in criminal behaviour caused public opinion to turn against prohibition.

In the 1932 Presidential Election, the Democratic Party candidate, Franklin D. Roosevelt, promised an early end to prohibition. In February 1933, Congress voted to repeal the Eighteenth Amendment. While the Twenty-first Amendment was making its way through the states, Roosevelt requested quick action to amend the Volstead Act by legalizing beer of 3.2 per cent alcoholic content by weight. Within a week both houses passed the beer bill, and added wine for good measure. On 22nd March 1933, Roosevelt signed the bill.

William E. Leuchtenburg, the author of Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal (1963), commented: "On April 7, 1933, beer was sold legally in America for the first time since the advent of prohibition, and the wets made the most of it. In New York, six stout brewery horses drew a bright red Busch stake wagon to the Empire State Building, where a case of beer was presented to Al Smith (the defeated Democratic candidate who opposed prohibition in 1928). In the beer town of St. Louis, steam whistles and sirens sounded by midnight, while Wisconsin Avenue in Milwaukee was blocked by mobs of celebrants standing atop cars and singing Sweet Adeline."

On this day in 1943 in Terebovlia, Ukraine, 1,100 Jews are murdered by Nazis. Total civilian losses during the war and German occupation in Ukraine are estimated at four million, including up to a million Jews who were murdered by the German Army and local Nazi collaborators. Officially they "had the mission to protect the rear of the troops by killing the Jews, Romani, Communist functionaries, active Communists, uncooperative slavs, and all persons who would endanger the security." However, a high percentage of those murdered were Jews.

On this day in 1950 the CIA agree to fund the Congress for Cultural Freedom. In August 1949, Arthur Koestler, Ruth Fischer, Franz Borkenau and Melvin Lasky met in Frankfurt to develop a plan where the CIA could be persuaded to fund a left-wing but anti-communist organisation. This plan was then passed onto Michael Josselson, who was chief of its Berlin station for Covert Action. Finally it reached Josselson's boss, Lawrence de Neufville. He later recalled: "The idea came from Lasky, Josselson and Koestler and I got Washington to give it the support it needed. I reported it to Frank Lindsay, and I guess he must have taken it to Wisner. We had to beg for approval. The Marshall Plan was the slush fund used everywhere by CIA at that time, so there was never any shortage of funds. The only struggle was to get approval."

The proposal reached Frank Wisner, the head of the Office of Policy Coordination (OPC), in January 1950. Wisner was in charge of "propaganda, economic warfare; preventive direct action, including sabotage, anti-sabotage, demolition and evacuation measures; subversion against hostile states, including assistance to underground resistance groups, and support of indigenous anti-Communist elements in threatened countries of the free world". Wisner accepted the proposal on 7th April and gave it an original budget of $50,000. Wisner put Michael Josselson in charge but insisted that Melvin Lasky and James Burnham should be "kept out of sight" for the time as they were too well known for their anti-communism. Wisner said he "feared their presence would only provide ammunition to Communist critics".

The first meeting of the Congress for Cultural Freedom took place in Frankfurt on 25th June, 1950. People who attended included Arthur Koestler, Arthur Schlesinger, James Burnham, Sidney Hook, Franz Borkenau, George Schuyler, Melvin Lasky, Hugh Trevor-Roper, James T. Farrell, Tennessee Williams, Ignazio Silone, David Lilienthal, Sol Levitas, Carson McCullers and Max Yergan.

Frances Stonor Saunders, the author of Who Paid the Piper: The CIA and the Cultural Cold War? (1999), pointed out: "Some delegates speculated who was footing the bill. The grand scale on which the Congress was launched at a time when Europe was broke seemed to confirm the rumour that this was not quite the spontaneous, independent event its organizers claimed. Hugh Trevor-Roper commented: "When I arrived I found the whole thing was orchestrated on so grandiose a scale... that I realized that... financially it must have been funded by some powerful government organization. So I took it for granted from the beginning that it was organized by the American government in one form or another. That seemed to be obvious from the start."

As Jason Epstein pointed out the objective of the group was to counter communism: "The Stalinists were still a very powerful gang... There was a good reason, therefore, to question the Stalinists right to culture." The conference was considered to be a success and an international committee was named, and included André Malraux, Bertrand Russell, Igor Straveinsky, Ignazio Silone, Benedetto Croce, T. S. Eliot and Karl Jaspers.

It has been argued by Frances Stonor Saunders that the Congress for Cultural Freedom was funded by the CIA as they wanted to promote what they called the Non-Communist Left (NCL). Arthur Schlesinger later recalled that the NCL was supported by leading establishment figures such as Chip Bohlen, Isaiah Berlin, Averell Harriman and George Kennan: "We all felt that democratic socialism was the most effective bulwark against totalitarianism. This became an undercurrent - or even undercover - theme of American foreign policy during the period."

Thomas Braden, the head of the International Organizations Division (IOD), was placed in charge of the Congress for Cultural Freedom.The objective of the IOD was to control potential radicals and to steer them to the right. Braden oversaw the funding of groups such as the National Student Association, Communications Workers of America, the American Newspaper Guild, the United Auto Workers, National Council of Churches, the African-American Institute and the National Education Association.

Braden later admitted that the CIA was putting around $900,000 a year into the Congress of Cultural Freedom. Some of this money was used to publish its journal, Encounter. Braden and the IOD also worked closely with anti-Communist leaders of the trade union movement such as George Meany of the American Federation of Labor. This money was used to fight Communism in its own ranks. As Braden said: "The CIA could do exactly as it pleased. It could buy armies. It could buy bombs. It was one of the first worldwide multinationals." Arthur Schlesinger has supported the role of the CIA during this period: "In my experience its leadership was politically enlightened and sophisticated."

The CIA funding of the Congress for Cultural Freedom remained a highly secret operation but in 1966 stories began to appear in the New York Times suggesting that the CIA had been secretly funding left-wing groups. This in fact, was not a new claim. Joseph McCarthy had made similar accusations in 1953. He had been given this information by J. Edgar Hoover who had described the Office of Policy Coordination (OPC) as "Wisner's gang of weirdos". In August, 1953, Richard Helms, Wisner's deputy at the OPC, told Cord Meyer, who was Braden's deputy at the International Organizations Division, that McCarthy and the FBI had accused him of being a communist. The FBI added to the smear by announcing it was unwilling to give Meyer "security clearance".

In September, 1953, Meyer was shown the FBI file against him. It included allegations that his wife, Mary Pinchot Meyer, was a former member of the American Labor Party. It also listed several people linked to Meyer who had "supported pro-Communist policies or have been associated with Communist front organizations or organizations pro-Communist in their sympathies." The list included the publisher Cass Canfield, the president and chairman of Harper & Brothers. Canfield had indeed been receiving money from the CIA to help publish left-wing but anti-communist books. He was along with Jason Epstein of Random House, who had blocked the publication of Léo Sauvage's The Oswald Affair - an Examination of the Contradictions and Omissions of the Warren Report, a key figure in the CIA sponsored Congress of Cultural Freedom.

McCarthy's assistant, Roy Cohn, argues in his book McCarthy (1968) that they had discovered that communist agents had infiltrated the CIA in 1953: "Our files contained allegations gathered from various sources indicating that the CIA had unwittingly hired a large numbers of double agents – individuals who, although working for the CIA, were actually communist agents whose mission was to plant inaccurate data…. We also wanted to investigate charges that the CIA had granted large subsidies to pro-Communist organizations." Cohn complained that this proposed investigation was stopped on the orders of the White House. "Vice-President Nixon was assigned to the delicate job of blocking it… Nixon spoke at length, arguing that an open investigation would damage national security, harm our relations with our allies, and seriously affect CIA operations, which depended on total secrecy… Finally, the three subcommittee members, not opposed to the inquiry before they went to dinner, yielded to Nixon's pressure. So, too, did McCarthy, and the investigation, which McCarthy told me interested him more than any other, was never launched."

Allen Dulles refused permission for the FBI to interrogate Frank Wisner and Cord Meyer and Hoover's investigation also came to an end. Joseph McCarthy was in fact right when he said that the CIA was funding what he considered to be pro-communist organisations. He was wrong however in believing they had infiltrated the organisation. Frances Stonor Saunders, the author of Who Paid the Piper: The CIA and the Cultural Cold War? (1999) has pointed out it was the other way round.

It might seem strange that the non-communist left should be paid to write articles and books attacking the Soviet Union. After all they would have done that anyway. However, the important aspect of this policy was to compromise these left-wing writers by paying them money or by funding their organisations. It also put them in position where they could call on their help in times of crisis such as the death of John F. Kennedy. The support of the Non-Communist Left was vitally important in the cover-up of the assassination.

Technically, Michael Josselson was subordinate to Lawrence de Neufville, but he rarely, if ever, tried to overrule him: "I saw Josselson every day, or if not, every week, and I would go to Washington with whatever he wanted to accomplish. If I agreed, which I usually did, I would try and help. I saw my job as trying to facilitate the development of Congress by listening to people like Josselson who knew better than I did. He did a wonderful job." Thomas Braden agreed: "Josselson is one of the world's unsung heroes. He did all this frenetic work with all the intellectuals of Europe, who didn't necessarily agree on much beyond their basic belief in freedom, and he was running around from meeting to meeting, from man to man, from group to group, and keeping them all together and all organized and all getting something done. He deserves a place in history." Arthur Schlesinger was another one who was impressed with the work Josselson did and described him as "an extraordinary man".

In October, 1955, Josselson, aged forty-seven, suffered a major heart attack. Cord Meyer decided to send recent CIA recruit, John Clinton Hunt, to work as his assistant to "lighten the load". In order to provide cover for Hunt, he officially applied for the job. Interviewed by Josselson in February 1956, Hunt was formally appointed to the Congress Secretariat shortly afterwards.

Frances Stonor Saunders, the author of Who Paid the Piper: The CIA and the Cultural Cold War? (1999) has argued: "During the height of the Cold War, the US government committed vast resources to a secret programme of cultural propaganda in western Europe. A central feature of this programme was to advance the claim that it did not exist. It was managed, in great secrecy, by America's espionage arm, the Central Intelligence Agency. The centrepiece of this covert campaign was the Congress for Cultural Freedom, run by CIA agent Michael Josselson... At its peak, the Congress for Cultural Freedom had offices in thirty-five countries, employed dozens of personnel, published over twenty prestige magazines, held art exhibitions, owned a news and features service, organized high-profile international conferences, and rewarded musicians and artists with prizes and public performances. Its mission was to nudge the intelligentsia of western Europe away from its lingering fascination with Marxism and Communism... Membership of this consortium included an assorted group of former radicals and leftist intellectuals whose faith in Marxism and Communism had been shattered by evidence of Stalinist totalitarianism."

Josselson became disillusioned by the United States foreign policy in 1960s. He was especially critical of its involvement in the Vietnam War: "In the 1950s our motivation was buttressed by America's historic promises... in the second half of the 1960s our individual values and ideals had been eroded by our intervention in Vietnam and by other senseless U.S. policies." According to Frances Stonor Saunders Josselson now looked to move the Congress for Cultural Freedom "away from the habits of Cold War apartheid, and towards a dialogue with the East."

In 1966 the New York Times published an article by Tom Wicker that suggested that the CIA had been funding the Congress for Cultural Freedom. On 10th May the newspaper published a letter from Stephen Spender, Melvin Lasky and Irving Kristol. "We know of no indirect benefactions... we are our own masters and part of nobody's propaganda" and defended the "independent record of the Congress for Cultural Freedom in defending writers and artists in both East and West against misdemeanors of all governments including that of the US."

The reason is that most of these sponsored journalists refused to support the government policy on Vietnam. In the case of I. F. Stone, he found it to his financial advantage to oppose the policy. Stone had barely 20,000 subscribers to I.F. Stone Weekly before the outbreak of the war. By 1969 he had over 70,000.

The story of CIA funding of Non-Communist Left journalists and organizations was fully broken in the press by a small-left-wing journal, Rapparts. The editor, Warren Hinckle, met a man by the name of Michael Wood, in January 1967, at the New York's Algonquin Hotel. The meeting had been arranged by a public relations executive Marc Stone (the brother of I.F. Stone). Wood told Hinckle that the National Student Association (NSA) was receiving funding from the CIA. At first Hinkle thought he was being set-up. Why was the story not taken to I.F. Stone?

However, after further research, Hinckle was convinced that the CIA had infiltrated the Non-Communist Left: "While the ADA-types and the Arthur Schlesinger model liberal kewpie dolls battled fascism by protecting their right flank with domestic Red-baiting and Cold War one-upmanship, the Ivy League delinquents who fled to the CIA – liberal lawyers, businessmen, academics, games-playing craftsmen – hatched a master plan of Germanic ambition that entailed nothing less than clandestine political control of the international operations of all important American professional and cultural organisations: journalists, educators, jurists, businessmen, et al. The standing CIA subsidy to the National Student Association was but one slice of a very complex pie." Hinckle even had doubts about publishing the story. Sol Stern, who was writing the article for Rapparts, "advanced the intriguing contention that such a disclosure would be damaging to the enlightened men of the liberal internationalistic wing of the CIA who were willing to provide clandestine money to domestic progressive causes."

Hinckle did go ahead with the story and took full-page advertisements in the Tuesday editions of the New York Times and Washington Post: "In its March issue, Ramparts magazine will document how the CIA has infiltrated and subverted the world of American student leaders, over the past fifteen years." For its exposé of the CIA, Rapparts, received the George Polk Memorial Award for Excellence in Journalism and was praised for its "explosive revival of the great muckraking tradition."

After the article was published Dwight Macdonald angrily asked Michael Josselson: "Do you think I would have gone on the Encounter payroll in 1956-57 had I known there was secret U.S. Government money behind it? One would hesitate to work even for an openly government-financed magazine... I think I've been played for a sucker." Josselson was not impressed with this reaction. He claimed that they were all aware that it had been funded by the CIA. As he pointed out, MacDonald had asked him in 1964 if he could employ his son, Nick, for the summer. "This, at a time when anybody who was anybody had at least heard rumours connecting the Congress to the CIA."

Lawrence de Neufville later claimed: "Who didn't know (the Congress for Cultural Freedom was being funded by the CIA), I'd like to know? it was a pretty open secret." John Clinton Hunt added, "They knew, and they knew as much as they wanted to know, and if they knew any more, they knew they would have had to get out, so they refused to know." Frances Stonor Saunders, the author of Who Paid the Piper: The CIA and the Cultural Cold War? (1999) has argued: "The list of those who knew - or thought they knew - is long enough". This included : Arthur Koestler, Louis Fischer, Arthur Schlesinger, James Burnham, Sidney Hook, Melvin Lasky, Sol Levitas, George Kennan, Jason Epstein, Robert Oppenheimer, Dwight MacDonald, Willy Brandt, Stuart Hampshire, Edward Shils, Daniel Bell, Mary McCarthy, Lionel Trilling, Diana Trilling and Sol Stein.

On 20th May 1967 Thomas Braden, the former head of the CIA's International Organizations Division, that had been funding the National Student Association, wrote an article that was published in the Saturday Evening Post entitled, I'm Glad the CIA is Immoral Braden admitted that for more than 10 years, the CIA had subsidized progressive magazines such as Encounter through the Congress for Cultural Freedom - which it also funded - and that one of its staff was a CIA agent. He also admitted that he had paid money to trade union leaders such as Walter Reuther, Jay Lovestone, David Dubinsky and Irving Brown.

According to Frances Stonor Saunders, the author of Who Paid the Piper: The CIA and the Cultural Cold War? (1999): "The effect of Braden's article was to sink the CIA's covert association with the Non-Communist Left once and for all." Braden later admitted that the article had been commissioned by CIA asset, Stewart Alsop.

John Clinton Hunt, a CIA agent who worked very closely with Braden at the International Organizations Division, pointed out in a revealing interview: "Tom Braden was a company man... if he was really acting independently, would have had much to fear. My belief is that he was an instrument down the line somewhere of those who wanted to get rid of the NCL (Non-Communist Left). Don't look for a lone gunman - that's mad, just as it is with the Kennedy assassination... I do believe there was an operational decision to blow the Congress and the other programs out of the water."

On this day in 1955 Winston Churchill resigns as Prime Minister because of failing health. Churchill returned to power after the 1951 General Election. Churchill's health continued to deteriorate and in 1955 he reluctantly retired from politics. Clare Sheridan remembers visiting his home in London after he left politics. She found him very depressed. He told her that he felt a failure. She replied: "How can you!" You beat the Nazis." Churchill remained sunk in gloom: "Yes.... we had to fight those Nazis - it would have been too terrible had we failed. But in the end you have your art. The Empire I believed in has gone."

On this day in 1962 Rona Robinson died.

Rona Robinson was born on 26th June 1884. She studied at Owens College and in 1905 she became the first woman in the United Kingdom to gain a first-class degree in chemistry. After leaving university Robinson researched dyes at her home, Moseley Villa, Withington.

Robinson went to work at the Altrincham Pupil-Teacher Centre where she taught Science and Mathematics. A fellow teacher was Dora Marsden. The women were both interested in women's suffrage and eventually joined the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU).

In March 1909 Robinson and Marsden resigned from the Pupil-Teacher Centre to become paid organisers of the WSPU. Later that month she was arrested with Emily Wilding Davison, Patricia Woodlock and Helen Tolson, at a demonstration outside the House of Commons. It was reported in The Times: "the exertions of the women, most of whom were quite young and of indifferent physique, had told upon them and they were showing signs of exhaustion, which made their attempt to break the police line more pitiable than ever." Robinson was sentenced to a month's imprisonment.

On 22nd September 1909 Rona Robinson, Charlotte Marsh, Mary Leigh and Laura Ainsworth conducted a rooftop protest at Bingley Hall, Birmingham, where Herbert Asquith was addressing a meeting from which all women had been excluded. Using an axe, Leigh removed slates from the roof and threw them at the police below. Sylvia Pankhurst later recalled: "No sooner was this effected, however, than the rattling of missiles was heard on the other side of the hall, and on the roof of the house, thirty feet above the street, lit up by a tall electric standard was seen the little agile figure of Mary Leigh, with a tall fair girl (Charlotte Marsh) beside her. Both of them were tearing up the slates with axes, and flinging them onto the roof of the Bingley Hall and down into the road below-always, however, taking care to hit no one and sounding a warning before throwing. The police cried to them to stop and angry stewards came rushing out of the hall to second this demand, but the women calmly went on with their work."

As Michelle Myall has pointed out: "The police attempted to move the two women by, among other methods, turning a hosepipe on them and throwing stones. However, Charlotte Marsh and Mary Leigh proved to be formidable opponents and were only brought down from the roof when three policeman dragged them down."