Ben Bradlee

Benjamin Bradlee, the son of Frederick Josiah Bradlee, was born in Boston on 26th August, 1921. "My father... rose from bank runner, to broker, than vice president of the Boston branch of an investment house called Bank America Blair Company. And then the fall. One day a Golden Boy. Next day, the Depression, and my old man was on the road trying to sell a commercial deodorant and molybdenum mining stock for companies founded and financed by some of his rich pals." (1) His great-uncle, Frank Crowninshield, was the former editor of Vanity Fair. (2)

One of his closest friends as a child was Richard Helms. (3) Bradlee attended St. Marks School in Southborough, Massachusetts. In the spring of 1936 polio broke out at the campus. "He was stricken with the fearful disease on the same day as a close friend. An ambulance that carried both boys dropped Mr. Bradlee at his Beacon Street home, then took Fred Hubbell to Massachusetts General Hospital. Mr. Bradlee was paralyzed from the waist down; Hubbell died. Even his polio proved to be an example of Mr. Bradlee’s lifelong good luck - bolstered, as usual, by his own determination. A young coach who had encouraged Mr. Bradlee’s athletic pursuits, a working-class Irishman from Boston named Leo Cronan, visited him in the Beverly house almost nightly during his summer with polio. Cronan introduced the idea of walking again at a time when Mr. Bradlee’s legs lay helpless and numb in clunky metal braces. Cronan got him on his feet and then helped him learn how to stand without the braces. Within eight weeks, thanks to rigorous rehabilitation, Mr. Bradlee was playing a clumsy game of golf. Two years later, he was playing varsity baseball for St. Mark’s. The physical therapy he did to fight off the effects of polio left him with a barrel chest and powerful arms for the rest of his life." (4)

In 1939 he won a place at Harvard University: "There was never a question that I would get into Harvard, or go to Harvard. My father had gone there. My grandfather had gone there. My grandfather had gone there, and many generations of Bradlees before him, a total of fifty-one, all the way back to 1795 with Caleb Bradlee. No alternatives were suggested, or contemplated, much less encouraged." (5)

Bradlee arrived at Harvard just as the Second World War broke out in Europe: "He decided to join the Naval ROTC to improve his initial posting in the war he and his contemporaries knew they would soon be fighting. With that threat hovering over him, Mr. Bradlee found it hard to be serious about college. Only in his third year, with the war ever more ominous, did he buckle down. He took a double academic load, which, after summer school, allowed him to graduate in August 1942 with majors in Greek and English." (6)

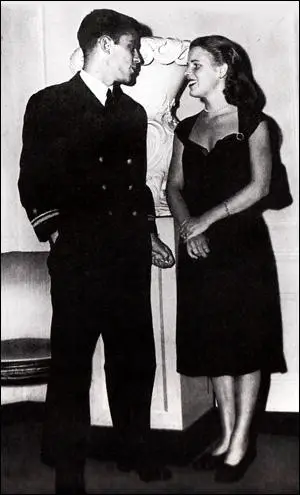

While at Harvard he met Jean Saltonstall, the daughter of Senator Leverett Saltonstall. "Jean and I were going steady... We were even talking about getting engaged, and wondered if it made any sense to get married before I went off to war. I was four months past my twentieth birthday, and Jean had turned twenty-one the month after Pearl Harbor. More than fifty years later, I wonder what we were wondering about: getting married, when we knew I was going to war in a destroyer in a few months, almost surely to the Pacific where destroyers were sinking like stones, when we knew I would be gone for months, if not for good." (7)

After his wedding he joined the United States Navy and for the next two years worked as a communications officer. (8) His duties included handling classified and coded cables. (9) "My regular non-battle job involved communications, the care and feeding of the machines which provided raw information to the ship, and of the men who operated and maintained those machines. This responsibility was more educating than Harvard, more exciting, more meaningful than anything I'd ever done. This is why I had such a wonderful time in the war. I just plain loved it." (10)

Ben Bradlee - 1945-1950

At the end of the war Bradlee accepted the offer of Roger Baldwin and went to work as a clerk for the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). Baldwin had told him that he "didn't know enough about civil liberties". Bradlee agreed and during this period he found out about people such as Nicola Sacco, Bartolomeo Vanzetti, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, Charles Edward Coughlin and Gerald L. K. Smith. "I'll never forget Roger Baldwin's tolerance, patience, and kindness to all. He dreaded meeting with Elizabeth Gurley Flynn. She smelled bad, he told me, and he disagreed with her on everything that mattered. He just shook his head at the hate preached by Smith and Coughlin, but he listened to them all, and he educated me." (11) Deborah Davis, the author of Katharine the Great (1979) points out that as the ACLU is an "organization that promotes various progressive causes, including conscientious objection to war. This job, so out of character for the young patriot, may or may not have been an intelligence assignment." (12)

In 1946 Bradlee purchased the New Hampshire Times. "We were quickly successful - in circulation. We wrote about illegal stills, missing children, empty mills, polluters and pollution, and farm problems like brucellosis, since I was also the farm editor. Before long, we were selling more copies on Sunday than either the Union or the Leader sold daily. That should have produced lucrative advertising, but the advertisers took a decidedly dim view of our crusading spirit, and stayed away in droves. We called ourselves independent, but in the good old Granite State 'independent' meant leftist if not Commie in those days." (13) After two years it "had more circulation than any other newspaper in the state." Bradlee eventually sold the newspaper to William Loeb III, a man he described as "the mercurial right-wing nut". (14)

According to Deborah Davis, family connections, bankers or politicians who knew Eugene Meyer, helped him to get a job with the Washington Post, as a crime reporter. (15) While working in Washington he socialised with Wistar Janney, a senior figure in the Central Intelligence Agency. (16) Bradlee also got to know Philip Graham, Eugene Meyer's son-in-law, and associate publisher of the newspaper. However, he was unhappy about being paid "the wrong side of $100 a week." As he pointed out: "Our friends were moving up in their law firms, or in the CIA, or on the various government staffs, and I felt impatient." (17)

Government Spokesman

In 1951 Frank Pace, the Secretary of the Army, invited him to work for the government. "He had never heard of me, but he was married to Wistar Janney's sister, and one night at the Janneys' he mentioned he was looking for a personal assistant/press person, who would travel with him, write speeches, and generally spread the gospel according to Pace... The money was good - almost twice what I was making as a reporter... but I couldn't conceive of being someone else's alter ego. And so I turned it down." However, he did agree to become assistant press attaché in the American embassy in Paris.

One of Ben Bradlee's first-tasks was to deal with the protests following the conviction of Ethel Rosenberg and Julius Rosenberg. "They were convicted of giving the Russians information vital to the manufacture of atomic weapons. The trial, the verdict, and especially the death sentence had absorbed - then enflamed - France... The American presence was over-whelming; American cash was everywhere, and the Rosenbergs being the symbolic rallying point for everyone who had a bone to pick with our government. Not just the Communists, who lived on anti-Americanism, but the intellectuals, the Socialists, and everyone who worried about McCarthyism - and the death penalty." (18)

The following year he joined the staff of the Office of U.S. Information and Educational Exchange, the embassy's special propaganda arm. As Deborah Davis has pointed out: "Bradlee's work for USIE, which is now the USIA, was in something called the Regional Publication Center, or the Regional Service Center. It produced films, magazines, research, speeches, and news items for use by the embassies, the Marshall Plan offices, and the CIA throughout Europe. It controlled Voice of America. The Paris Center was controlled from Washington by a man named Edward Ware Barrett, an assistant secretary of state for public affairs and a seventeen-year veteran of Newsweek." (19) It was claimed by Christopher Reed that "During this period, according to a US justice department memo, Bradlee promulgated CIA-directed European propaganda urging the controversial execution of the convicted American spies Ethel and Julius Rosenberg." (20)

If you find this article useful, please feel free to share on websites like Reddit. Please visit our support page. You can follow John Simkin on Twitter, Google+ & Facebook or subscribe to our monthly newsletter.

While at the USIE, Bradlee worked with E. Howard Hunt and Alfred Friendly. Hunt later recalled that Alger Hiss caused problems for the organization: "As soon as I arrived in Paris, I was plunged into a maelstrom of administrative and political activity. The personnel, like myself, had mostly been hired through their social or political ties with people in power, and they had varying degrees of competence. My immediate superior was an enthusiastic Democrat named Alfred Friendly... Ideology reared its ugly head when a high-level U.S. State Department officer, Alger Hiss, was accused of passing U.S. secrets to the Soviets. Many of the staff members knew Hiss personally and promoted his innocence; I almost came to blows with a few of the accused man's friends when I refused to uphold their stance." (21)

Ben Bradlee in Paris

Bradlee was officially employed by USIE until 1953, when he became the Paris correspondent for Newsweek. Later, Nina Burleigh argued: "He (Bradlee) was Harvard-educated and spoke French fluently but camouflaged his pedigree behind a streetwise front. With his macho manner, savvy, and profanity, he epitomized the finger-snapping cool of the Hollywood Rat Pack... On first meeting Bradlee, one male acquaintance thought that Newsweek's Washington bureau chief was a bookie." (22)

In August 1954, Bradlee met Antoinette Pinchot Pittman, and her sister, Mary Pinchot Meyer, who was married to senior CIA officer, Cord Meyer, a key figure in Operation Mockingbird, a CIA program to influence the American media. "The weekend that changed my life forever came in August of 1954, when our friends the Pinchot sisters hit town. Mary Pinchot Meyer, mother of three and wife of Cord Meyer, war hero turned World Federalists president and CIA biggie, and Antoinette Pinchot Pittman, mother of four, wife of Steuart Pittman, a Washington lawyer. They were both members of our Washington crowd - on the last leg of a European tour, to which they had treated themselves after seven years of diapers and dishes." (23)

Bradlee fell in love with Antoinette (Tony) and after divorcing his first wife, Jean Saltonstall Bradlee, the couple were married in Paris. Antoinette was also a close friend of Cicely d'Autremont, who was married to James Angleton. Bradlee worked closely with Angleton in Paris. At the time Angleton was liaison for all Allied intelligence in Europe. (24) His deputy was Richard Ober, a fellow student of Bradlee's at Harvard University. (25)

In February 1956 Bradlee created a great deal of controversy when he interviewed members of the Front de Libération Nationale (FLN). They were Algerian guerrillas who were in rebellion against the French government at the time. "I flew back to Paris, and next morning went to see Ambassador Dillon to let him know what I had been up to in Algeria. As I was leaving the embassy I got a call from my maid, telling me that the cops were scouring the Place des Vosges for me. And when I got back to my office on the rue de Berri in a taxi, I was suddenly surrounded by cops and black Citroens. Two cops got me by the elbows, lifting me off the pavement, and asked me to come along with them." (26) As a result of these interviews, Bradlee was expelled from France. Deborah Davis argues that Bradlee's activities had all the "earmarks of an intelligence operation". (27)

John F. Kennedy

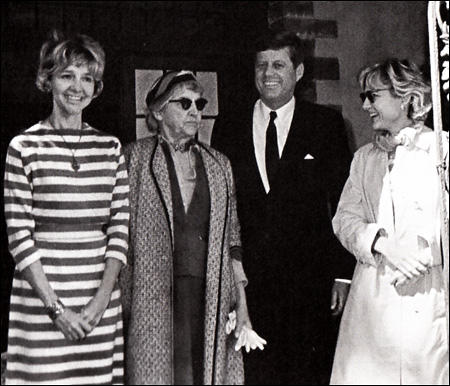

Bradlee now began working at Newsweek in Washington. In early 1959 Bradlee went to a dinner held by Douglas Dillon. That night Bradlee met John F. Kennedy and Jacqueline Kennedy. He later recalled: "I sat next to Jackie, and Jack sat next to Tony. We came home together, and by the time we said good night, we were friends, comfortable together and looking forward to the next time... When I got to know Kennedy, I kind of staked him out as part of my own territorial imperative, and as he prospered, so did I... Little by little, it was accepted by the rest of the Newsweek Bureau and by New York that Kennedy was mine. If a quote was needed, I was asked to get it, and without really understanding what running for president entailed, or where it would all end, I was embarked on a brand-new journey. Nothing in my education or experience had led me to conceive of the possibility that someone I really knew would hold that exalted job. The field in front of him was filled with mines. His age - at forty-three, he would be the youngest man ever elected president, the first one born in the twentieth century. His religion - too much of America believed that a Catholic president would have to take orders from the pope in Rome. His health - he had been given the last rites several times, and had been referred to by India Edwards, chairman of the Citizens for Lyndon B. Johnson National Committee, as a "spavined little hunchback." His father Joseph P. Kennedy's reputation was secure as a womanizing robber baron, who had been anti-war and seen as pro-German while he was Ambassador to Britain during World War II, and pro-McCarthy during the fifties." (28)

Newsweek assigned Ben Bradlee to cover Kennedy full time as he travelled the country in pursuit of the presidency. "I flew to Los Angeles the week before the Democratic National Convention in July 1960, and a week before Kennedy and his team arrived. If it's a close race, the pre-convention cover story is one of the toughest news magazine assignments there is. The cover should be the nominee, but has to be selected on Wednesday, at least five days before the nominee is selected. The story must be finished Saturday afternoon, two days before. If you pick the right candidate, the editors are geniuses. If you pick the wrong man, you have a big problem, like looking for work. Kennedy had won the big primaries that counted, and was not threatened by the other Democratic candidates. I had persuaded Newsweek's editors that Kennedy would be the nominee, primarily because Larry O'Brien, Kennedy's political wizard, was the best delegate counter in the business and I had checked his last best delegate count. And so Kennedy's picture was on our pre-convention cover." (29)

Bradlee was with John F. Kennedy on election night. "Finally. Election night was endless, as Kennedy stalled a few critical votes short of victory on Tuesday night. Illinois, California, Michigan, and Minnesota were still undecided, and it was well into Wednesday before his election was official. When Tony and I at last got back to the Yachtsman Motel in Hyannis Port, there was an invitation for supper that night with Jack and Jackie at the Kennedys' house in the Kennedy compound. It was just us plus Bill Walton, the charming former journalist (Time-Life, New Republic) turned artist turned Kennedy worker (he had run the Kennedy campaign in Arkansas). We arrived early, Tony eight months pregnant, and were greeted by Jackie in the same condition. Kennedy came downstairs a few minutes later, and before anyone could say anything, he smiled and said, "Okay, girls. We won. You can take the pillows out now." Over drinks, we talked nervously about what we should call him. "Mr. President" sounded awesome, and he was not yet president." (30)

Sale of Newsweek

In 1961 Richard Helms tipped off Bradlee that his grandfather, Gates White McGarrah, a board member of the Vincent Astor Foundation, was willing to sell Newsweek. (31) Bradlee went to Philip Graham with the story. "Essentially my pitch to him was that Newsweek could be made into something really important by the right owner, if only the right people were freed to practice the kind of journalism Graham knew all about; that Newsweek was about to be sold to someone (whomever) who wouldn't understand or appreciate its potential; that it wouldn't require a lot more money... maybe a few thousand bucks worth of severance pay, and maybe Newsweek was just the right property for The Washington Post to make a move toward national and international stature." (32) Graham was interested in buying the journal and gave Bradlee a handwritten check for $1 million to convey to McGarrah as a down payment. (33)

Ben Bradlee later admitted that the purchase of the journal changed his life: "It turned out to be an incredible deal for all of us at Newsweek, especially me, but it was also a once-in-a-lifetime deal for The Washington Post. The price was $50 a share, for the total of $15 million. But Newsweek had $3 million cash in the bank, plus a half-interest in the San Diego TV station, later sold for another $3 million. So the real price was only $9 million... Newsweek's profits have averaged $15 million a year for the last thirty years... My reward was Washington Post stock, as a finder's fee, and an extraordinary generous expression of appreciation. It changed my life, as much as the Post's purchase of Newsweek changed theirs." (34)

Mary Pinchot Meyer

Mary Pinchot Meyer, who was Antoinette Bradlee's sister, divorced Cord Meyer. The Bradlees set up Mary's apartment and art studio in their converted garage. In January, 1962, Mary began a sexual relationship with President John F. Kennedy. (35) Charles Bartlett, a journalist who ran the Washington bureau of the Chattanooga Times, and a close friend of Kennedy's became concerned about the affair: "I really liked Jack Kennedy. We had great fun together and a lot of things in common. We had a very personal, close relationship... Jack was in love with Mary Meyer. He was certainly smitten by her, he was heavily smitten. He was very frank with me about it, that he thought she was absolutely great.... It was a dangerous relationship." (36)

In April 1962 Mary Meyer began visiting Timothy Leary, the director of research projects at Harvard University. According to his biography, Flashbacks: "She appeared to be in her late thirties. Good looking. Flamboyant eyebrows, piercing green-blue eyes, fine-boned face. Amused, arrogant, aristocratic." Leary goes on to claim that she said "I want to learn how to run an LSD session... I have this friend who's a very important man. He's impressed by what I've told him about my own LSD experiences and what other people have told him. He wants to try it himself." (37)

Nina Burleigh has argued: "Kennedy's sexual escapes were legendary in Georgetown. To the rest of America he was a family man with a beautiful wife, a man of caution, wit, and strategy. In private he was dazzlingly reckless.... Some of his most infamous sexual liaisons were with real actresses on the West Coast, women procured with the help of his brother-in-law, the actor Peter Lawford. Lawford ran with Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin, who converged with Kennedy and various actresses and prostitutes for wild parties at the Lawford beach house in Santa Monica." (38) Bobby Baker claims that Kennedy told him: "You know, I get a migraine headache if I don't get a strange piece of ass every day." (39)

White House gate logs show Mary Pinchot Meyer signed in to see the president at or around 7.30 p.m. on fifteen occasions between October 1961 and August 1963, always when Jacqueline Kennedy is known to have been away from Washington, with one exception when her whereabouts are not verifiable by White House records or news reports. "The gate logs do not tell the entire story of who was in the White House, because there were other entrances and many occasions when people have said they were inside the White House without being signed... The fact that Mary Meyer's name is so often entered means she was not hidden and was probably there more often than the logs indicate." (40) Kenny O'Donnell told Leo Damore, that in October 1963 Kennedy told him that he "was deeply in love with Mary, that after he left the White House he envisioned a future with her and would divorce Jackie." (41)

Ben Bradlee later insisted that he knew nothing of Kennedy’s sex life at the time, including his affair with his sister-in-law. (42) In his autobiography, The Good Life (1995) he claimed: "like everyone else, we had heard reports of presidential infidelity, but we were always able to say we knew of no evidence, none... Of course, I had heard reports of girlfriends. Everyone had. Even my father, who was trying to get up the nerve in 1960 to vote for a democrat for the first time in his life, asked me about rumors circulating among his friends that Kennedy was a 'fearful girler'." (43)

Bradlee admits that he did once talk to Kennedy about these rumours. It was at the time that journalists were investigating a story that he was still involved with Florence Pritchett Smith, a woman he had nearly married in 1944. (44) She was married to Earl E. T. Smith, a family friend. Seymour Hersh has argued: "Many historians have said that Kennedy had a long-standing romance with Smith's wife, Florence." (45) When Bradlee asked Kennedy about this denied it, "They're always trying to tie me to some story about a girl, but they can't - there are none." (46)

Assassination of John F. Kennedy

Ben Bradlee was in the lobby of the National Press Building when he heard the news that John F. Kennedy had been shot. He returned to his office in Newsweek: "Colleagues were crowded around the ticker, dazed, watching the deadly bursts of unbelievable, wrenching news, worsening every few seconds... And then, so suddenly, he was dead. Life changed, forever, in the middle of a nice day, at the end of a good week, in a wonderful year of what looked like an extraordinary decade of promise. It would take months before we would begin to understand how, but the inevitability of wrenching change was plain as tears."

Kennedy had died on a Friday. Bradlee claims that the journal's main article about the Bobby Baker scandal and its links with Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson had already been printed: "Fridays are the beginning of the end of a week in the life of a news magazine. The covers have long since been printed, waiting for the rest of the book. All the features - the back of the book-have been edited and typeset. The leads of the news sections are being written, edited, rewritten, and rewritten again. The printed cover of the impending scandal involving Bobby Baker, LBJ's protégé, was scrapped. The entire magazine went out the window and we began all over again."

Bradlee was asked to write an "appreciation" of Kennedy: "I had only hours to deadline; I wasn't comfortable writing about myself, and my emotions; I didn't really know yet what I felt. I wondered how I could write anything without misusing the first person singular. But I said I'd try. When I started to write, I started to cry. Never mind writing about emotions. I couldn't deal with them. In the middle of crying, reporters would burst in with new copy, editors in New York would call. And I didn't get very far. At about six-thirty that night, Nancy Tuckerman, Jackie Kennedy's social secretary, called to ask us to be at the White House about seven, to go out to Bethesda Naval Hospital, where the president's widow - alongside the president's body - was headed from Dallas. Tuckerman emphasized that she was acting on her own, and that I was being invited as a friend, not a journalist. Except for my own piece, the bureau's assignments were under control, and I thought I would be back in a few hours to finish what I had to do, or run up the white flag."

Bradlee met Jacqueline Kennedy at the Bethesda Naval Hospital: "There is no more haunting sight in all the history I've observed than Jackie Kennedy, walking slowly, unsteadily into those hospital rooms, her pink suit stained with her husband's blood. Her eyes still stared wide open in horror. She fell into our arms, in silence, then asked if we wanted to hear what happened. But the question was barely out of her lips, when she felt she had to remind me that this was not for next week's Newsweek. My heart sank to realize that even in her grief she felt that I could not be trusted, that I was friend and stranger. Perhaps because of her warning, I remember almost nothing of what she said." (47)

Ben and Antoinette Bradlee spent the next couple of weekends at the Kennedys' country house in Middleburg, "trying with no success to talk about something else, or someone else". On 20th December, 1963, Jackie sent Bradlee a letter: "Something that you said in the country stunned me so - that you hoped I would marry again. You were close to us so many times. There is one thing that you must know. I consider that my life is over and I will spend the rest of it waiting for it really to be over." (48)

Death of Mary Pinchot Meyer

Timothy Leary has claimed that a few days after John F. Kennedy had been killed he received a disturbing phone call from Mary Pinchot Meyer. He wrote in his autobiography, Flashbacks (1983): Ever since the Kennedy assassination I had been expecting a call from Mary. It came around December 1. I could hardly understand her. She was either drunk or drugged or overwhelmed with grief. Or all three." Meyer told Leary: "They couldn't control him any more. He was changing too fast. They've covered everything up. I gotta come see you. I'm afraid." (49)

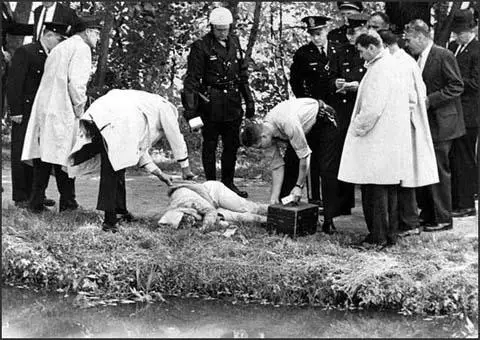

On 12th October, 1964, Mary Pinchot Meyer was shot dead as she walked along the Chesapeake and Ohio towpath in Georgetown. Henry Wiggins, a car mechanic, was working on a vehicle on Canal Road, when he heard a woman shout out: "Someone help me, someone help me". He then heard two gunshots. Wiggins ran to the edge of the wall overlooking the towpath. He later told police he saw "a black man in a light jacket, dark slacks, and a dark cap standing over the body of a white woman." (50)

Mary appeared to be killed by a professional hitman. The first bullet was fired at the back of the head. She did not die straight away. A second shot was fired into the heart. The evidence suggests that in both cases, the gun was virtually touching Mary’s body when it was fired. As the FBI expert testified, the “dark haloes on the skin around both entry wounds suggested they had been fired at close-range, possibly point-blank”. (51)

Ben Bradlee points out that the first he heard of the death of Mary Pinchot Meyer was when he received a phone-call from Wistar Janney, his friend who worked for the CIA: "My friend Wistar Janney called to ask if I had been listening to the radio. It was just after lunch, and of course I had not. Next he asked if I knew where Mary was, and of course I didn't. Someone had been murdered on the towpath, he said, and from the radio description it sounded like Mary. I raced home. Tony was coping by worrying about children, hers and Mary's, and about her mother, who was seventy-one years old, living alone in New York. We asked Anne Chamberlin, Mary's college roommate, to go to New York and bring Ruth to us. When Ann was well on her way, I was delegated to break the news to Ruth on the telephone. I can't remember that conversation. I was so scared for her, for my family, and for what was happening to our world. Next, the police told us, someone would have to identify Mary's body in the morgue, and since Mary and her husband, Cord Meyer, were separated, I drew that straw too." (52)

Peter Janney, the author of Mary's Mosaic (2012) has questioned this account of events provided by Bradlee. "How could Bradlee's CIA friend have known 'just after lunch' that the murdered woman was Mary Meyer when the victim's identity was still unknown to police? Did the caller wonder if the woman was Mary, or did he know it, and if so, how? This distinction is critical, and it goes to the heart of the mystery surrounding Mary Meyer's murder." (53)

That night Antoinette Pinchot Bradlee received a telephone call from Mary's best friend, Anne Truitt, an artist living in Tokyo. She told her that it "was a matter of some urgency that she found Mary's diary before the police got to it and her private life became a matter of public record". (54) Mary had apparently told Anne that "if anything ever happened to me" you must take possession of my "private diary". Ben Bradlee explains in The Good Life (1995): "We didn't start looking until the next morning, when Tony and I walked around the corner a few blocks to Mary's house. It was locked, as we had expected, but when we got inside, we found Jim Angleton, and to our complete surprise he told us he, too, was looking for Mary's diary." (55)

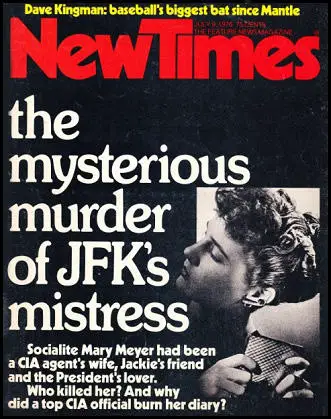

James Jesus Angleton later claimed that he had also received a telephone call from Anne Truitt. His wife, Cicely Angleton, confirmed this in an interview given to Nina Burleigh. (56) However, an article by Ron Rosenbaum and Phillip Nobile, in the New Times on 9th July, 1976, gives a different version of events with the Angleton's arriving at Mary's house that evening to attend a poetry reading and that at this stage they did not know she was dead. (57)

Joseph Trento, the author of Secret History of the CIA (2001), has pointed out: "Cicely Angleton called her husband at work to ask him to check on a radio report she had heard that a woman had been shot to death along the old Chesapeake and Ohio towpath in Georgetown. Walking along that towpath, which ran near her home, was Mary Meyer's favorite exercise, and Cicely, knowing her routine, was worried. James Angleton dismissed his wife's worry, pointing out that there was no reason to suppose the dead woman was Mary - many people walked along the towpath. When the Angletons arrived at Mary Meyer's house that evening, she was not home. A phone call to her answering service proved that Cicely's anxiety had not been misplaced: Their friend had been murdered that afternoon." (58)

Editor of Washington Post

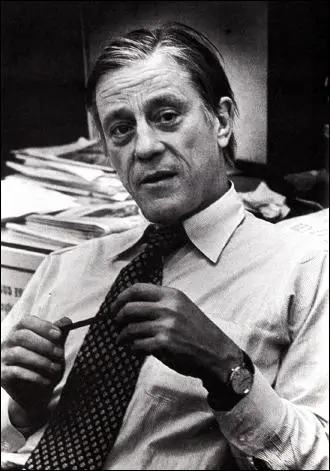

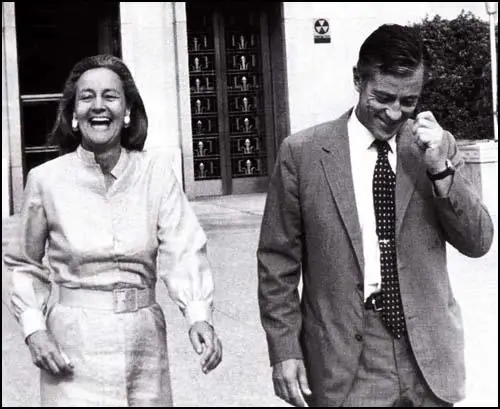

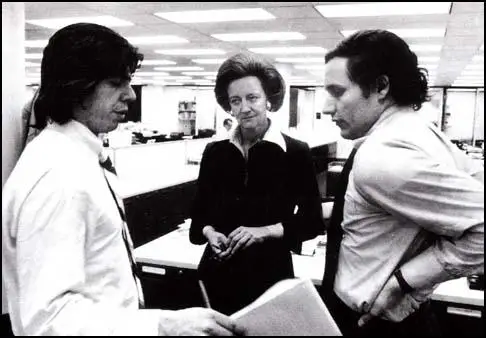

In July 1965 Katharine Graham appointed Bradlee as assistant managing editor of the Washington Post under Alfred Friendly, his former colleague at Office of U.S. Information and Educational Exchange. Graham then requested Walter Lippmann to suggest to Friendly that he should retire in order that Bradlee could take over his job as managing editor. After a meeting with Graham he agreed to leave the organisation. Graham later explained why she appointed him: "Then and always, Ben was charismatic. He was good-looking in an unconventional way, funny, street-smart, and political - all of which stood him in good stead. What was also important was how hard he worked. In his determination to learn, he worked into the night and on Saturdays, too." (59)

Robert G. Kaiser has argued that his appointment was a great success: "From the moment he took over The Washington Post newsroom in 1965, Mr. Bradlee sought to create an important newspaper that would go far beyond the traditional model of a metropolitan daily. He achieved that goal by combining compelling news stories based on aggressive reporting with engaging feature pieces of a kind previously associated with the best magazines. His charm and gift for leadership helped him hire and inspire a talented staff and eventually made him the most celebrated newspaper editor of his era." (60)

Barry Sussman worked under Ben Bradlee at the Washington Post: "In some ways, the newsroom was a playground for Bradlee. He walked around flipping a softball, often called loudly across dozens of desks. He was impatient with stories that bored him. What Bradlee wanted were exposes of all kinds, well-written magazine-type life-style pieces, and coverage of government that had life to it. Procedural or institutional stories left him cold. Government to him was the interplay of people and power - politics - and that was what he wanted the news pages of the Washington Post to mirror. More than anything else, Bradlee loved politics." (61)

Another journalist at the newspaper who was impressed by Bradlee was David Von Drehle: "Charisma is a word, like thunderstorm or orgasm, which sits pretty flat on the page or the screen compared with the actual experience it tries to name. I don’t recall exactly when I first looked it up in the dictionary and read that charisma is a 'personal magic of leadership,' a 'special magnetic charm.' But I remember exactly when I first felt the full impact of the thing itself. Benjamin Crowninshield Bradlee was gliding through the newsroom of the Washington Post, pushing a sort of force field ahead of him like the bow wave of a vintage Chris-Craft motor yacht. All across the vast expanse of identical desks, faces turned toward him - were pulled in his direction - much as a field of flowers turns toward the sun. We were powerless to look away." (62)

Graham was pleased with the way Bradlee edited the Washington Post and in 1968 she appointed him vice president of the company. Bradlee and Graham were strong supporter of the Vietnam War. This was partly because of the support the newspaper gave to Lyndon B. Johnson. Graham's biographer, Deborah Davis has argued: "Supremely competent as a businesswoman, working at nothing except building a powerful news machine, Katharine reflected no more deeply upon the purpose of such an instrument than to want it to express her loyalty to the politicians toward whom she felt like a sister or a wife. This vulnerability, and the sublimation of her feelings into intellectual, emotional, and political alliances, seemed to be a fundamental aspect of her widowhood." (63)

The Pentagon Papers

Daniel Ellsberg was a member of the McNamara Study Group that in 1968 had produced the classified History of Decision Making in Vietnam, 1945-1968. Ellsberg, disillusioned with the progress of the war, believed this document should be made available to the public. He gave a copy of what later became known as the Pentagon Papers to William Fulbright. However, he refused to do anything with the document, so Ellsberg gave a copy to Phil Geyelin of the Washington Post. Bradlee and Katharine Graham decided against publishing the contents on the document.

Ellsberg now went to the New York Times and they began publishing extracts from the document on 13th June, 1971. This included information that Dwight Eisenhower had made a secret commitment to help the French defeat the rebellion in Vietnam. The document also showed that John F. Kennedy had turned this commitment into a war by using a secret "provocation strategy" that led to the Gulf of Tonkin incidents and that Lyndon B. Johnson had planned from the beginning of his presidency to expand the war.

Ben Bradlee wrote: "Six full pages of news stories and top-secret documents, based on a 47-volume, 7,000-page study, "History of U.S. Decision-Making Process on Vietnam Policy, 1945-1967." The New York Times had obtained a copy of the study, and had assigned more than a dozen top reporters and editors to digest it for three months, and write dozens of articles... We found ourselves in the humiliating position of having to rewrite the competition. Every other paragraph of the Washington Post story had to include some form of the words 'according to the New York Times,' blood - visible only to us - on every word." (64)

Bradlee was criticised by his journalists for failing to break this story. He now made attempts to catch up and on June 18, 1971, the Washington Post began publishing extracts from another copy of the document. However, Bradlee concentrated on the period when Dwight Eisenhower was in power. The first story reported on how the Eisenhower administration had delayed democratic elections in Vietnam. This marked a change in direction and "established Katharine Graham as a great American woman in the 1970s, a leader of the moral opposition to the Nixon administration, the truth of the matter was that her newspaper had done a bad job handling the moral issues of the 1960s, as bad as that of the politicians themselves. The significance of the Pentagon Papers was that they put her belatedly on the right side of the issues." (65)

Richard Nixon now made attempts to prevent anymore extracts from the Pentagon Papers being published. Murray Gurfein, the federal judge who heard the case, ruled: “The security of the nation is not at the ramparts alone. Security also lies in the value of our free institutions. A cantankerous press, an obstinate press, a ubiquitous press must be suffered by those in authority in order to preserve the even greater values of freedom of expression and the right of the people to know.” (66) The Supreme Court ruled against Nixon and Hugo Black commented that the two newspapers "should be commended for serving the purpose that the Founding Fathers saw so clearly". "The next day, both of us resumed our stories about the Pentagon Papers. For the first time in the history of the American republic, newspapers had been restrained by the government from publishing a story - a black mark in the history of democracy. We had won." (67)

Watergate

While editor of the Washington Post, Bradlee promoted the career of Bob Woodward. Like Bradlee, Woodward had been a communications officer for naval intelligence. "Bob Woodward, who came to the Washington Post in 1971 with a background almost identical to Bradlee's own: he too had been a communications officer for naval intelligence. Woodward had enlisted in 1965 after graduating from Yale and had handled coded cables on a guided-missile ship. Later he had been transferred to the Pentagon and during the first year of the Nixon presidency had been an intelligence liaison between the Pentagon and the White House." (68) Bradlee claimed "Woodward... one of the new kids on the staff, who had impressed everyone with his skill at finding stories wherever we sent him." (69) Katharine Graham also thought highly of Woodward and claimed he "was conscientious, hardworking, and driven." (70)

On 17th June, 1972, Joseph Califano, counsel to both the Democratic Party and the Washington Post, informed Bradlee's team that five men had broken into the headquarters of the Democratic National Committee at Watergate. It was decided Woodward should cover the story. "He spent all day behind the police lines, calling in to the city desk regularly with all the vital statistics." When Frank Sturgis, Virgilio Gonzalez, Eugenio Martinez, Bernard L. Barker and James W. McCord appeared in court, Woodward was sitting in the front row when he heard McCord being asked what kind of a "retired government worker" he was. McCord replied "CIA". Bradlee later commented: "No three letters in the English language, arranged in that particular order, and spoken in similar circumstances, can tighten a good reporter's sphincter faster than C-I-A". (71)

It appeared that the men had been involved in the wiretapping the conversations of Larry O'Brien, chairman of the Democratic National Committee. Carl Bernstein was chosen to work with Woodward on the story. Katharine Graham admitted this was a strange choice and the two men had never worked on a story together. "Carl Bernstein... had been at the Washington Post since the fall of 1966 but had not distinguished himself. He was a good writer, but his poor work-habits were well-known throughout the city room even then, as was his famous roving eye. In fact, one thing that stood in the way of Carl's being put on the story was that Ben Bradlee was about to fire him." (72)

The phone number of E. Howard Hunt was found in the address book of one of the burglars, Bernard L. Barker. Hunt records in his autobiography, American Spy (2007) that he received a telephone-call from Woodward: "Some men have been arrested, and one of them had your name in his notebook. His name is Barker. Is he a friend of yours?" Hunt admitted that replied without thinking: "Oh my God." (73) Woodward discovered that Hunt, like McCord, was a former officer in the CIA and worked for them from 1949 to 1970. He was currently working as a consultant to Charles Colson, special counsel to President Richard Nixon. Woodward and Bernstein were now able to link the break-in to the White House. (74)

Carroll Kilpatrick, the Washington Post White House correspondent, saw a picture of James W. McCord and immediately recognized him as someone who worked for Nixon's reelection committee. Bradlee pointed out: "In less than forty-eight hours, we had traced what the Republicans were calling a 'third-rate burglary' into the White House, and into the very heart of the effort to win Richard Nixon a second term. We didn't know it yet, but we were out front, never to be headed, in the story of our generation, the story that put us all on the map." (75)

According to Bob Woodward, one of his best sources was a man that was given the nickname of Deep Throat. He claims that on 19th June, he telephoned a man who he called "an old friend" for information about the burglars. This man, who Woodward claims was a high-ranking federal employee, was willing to help Woodward as long as he was never named as a source. During their first telephone conversation Deep Throat insisted on certain conditions. According to All the President's Men: "His identity was unknown to anyone else. He could be contacted only on very important occasions. Woodward had promised he would never identify him or his position to anyone. Further, he, had agreed never to quote the man, even as an anonymous source. Their discussions would be only to confirm information that had been obtained elsewhere and to add some perspective." (76)

Bradlee claims that Deep Throat was Woodward's source. However, Deborah Davis, the author of Katharine the Great (1979), claims this is not true: "Bradlee knew him (Deep Throat), had known him far longer than Woodward. There is a possibility that Woodward had met him while working as an intelligence liaison between the Pentagon and the White House, where Deep Throat spent a lot of time, and that he considered Woodward trustworthy, or useful, and began talking to him when the time was right. It is equally likely, though, that Bradlee, who had given Woodward other sources on other stories, put them in touch after Woodward's first day on the story, when Watergate burglar James McCord said at his arraignment hearing that he had once worked for the CIA." (77) Davis suggests that Deep Throat was Bradlee's CIA friend, Richard Ober. Woodward later identified Deep Throat as Mark Felt, who worked for FBI. (78) However, it is clear from the evidence that Woodward claimed Deep Throat supplied, came from a variety of different sources, including the CIA and the White House. (79)

Carl Bernstein concentrated on researching the background of Bernard L. Barker. Born in Cuba he joined the National Police and worked as an assistant to the Chief of Police with the rank of sergeant. Later he was recruited by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and worked for them as an undercover agent. He also did work for the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). When Fidel Castro successfully overthrew Fulgencio Batista, Barker and his family moved to Miami (January 1960). Barker became a significant figure in the Cuban exile community. He remained a CIA agent and worked under the direction of Frank Bender. Later that year Barker was assigned to work under E. Howard Hunt. Barker's new job was to recruit men into the 2506 Brigade. These men eventually took part in the disastrous Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba.

Bernstein went to Miami to talk to the prosecutor there who had started his own Watergate investigation. Martin Dardis told Bernstein that he had traced money recovered at the Watergate to the Nixon re-election campaign (CRP). He discovered that a $25,000 check had come from Kenneth H. Dahlberg, a businessman who had been fundraising for Richard Nixon. He told Woodward that he turned over all the money he raised to Maurice Stans, CRP's finance chairman. On 1st August, 1972, the Washington Post ran the story about this connection between the Watergate burglars and Nixon. (80)

On 29th September, Bernstein phoned John N. Mitchell and asked him to comment on a story that he had controlled a "secret fund" when he was Attorney General. Mitchell replied: "All that crap you're putting in the paper. It's all been denied. Katie Graham's going to get her tit caught in a big fat wringer if that's published. Good Christ! That's the most sickening thing I've ever heard... You fellows got a great ball game. As soon as you're through paying Ed Williams and the rest of those fellows, we're going to do a little story on all of you." (81)

Woodward and Bernstein eventually discovered that the FBI had identified large-scale corruption. On 10th October, 1972, the Washington Post reported: "FBI agents have established that the Watergate bugging incident stemmed from a massive campaign of political spying and sabotage conducted on behalf of President Nixon's re-election and directed by officials of the White House and the Committee for the Re-election of the President. The activities, according to information in FBI and Department of Justice files, were aimed at all the major Democratic presidential candidates and - since 1971 - represented a basic strategy of the re-election effort."

The article went on to argue: "During the Watergate investigation federal agents established that hundreds of thousands of dollars in Nixon campaign contributions had been set aside to pay for an extensive undercover campaign aimed at discrediting individual Democratic presidential candidates and disrupting their campaigns... Following members of Democratic candidates' families; assembling dossiers of their personal lives; forging letters and distributing them under the candidates' letterheads; leaking false and manufactured items to the press; throwing campaign schedules into disarray; seizing confidential campaign files and investigating the lives of dozens of campaign workers. In addition, investigators said the activities included planting provocateurs in the ranks of organizations expected to demonstrate at the Republican and Democratic conventions; and investigating potential donors to the Nixon campaign before their contributions were solicited." (82)

On 15th October, 1972, Woodward and Bernstein revealed that Nixon's appointments secretary, Dwight Chaplin, and an ex-White House aide, Donald Segretti, were integral parts of the spying and sabotage operation. Evidence also emerged that others close to Nixon, such as Jeb Magruder, H. R. Haldeman and John Ehrlichman, were involved in controlling the White House secret fund, used to finance all political sabotage and payoffs. When this information was published, Ben Bradlee was accused of mounting a political smear campaign against Nixon during the 1972 Presidential Campaign.

Bob Dole, the chairman of the Republican Party, made a speech on 23rd October, attacking Bradlee: "The greatest political scandal of this campaign is the brazen manner in which, without benefit of clergy, The Washington Post has set up house-keeping with the McGovern campaign... Now, Mr. Bradlee, an old Kennedy coat-holder, is entitled to his views. But when he allows his paper to be used as a political instrument of the McGovernite campaign; when he himself travels the country as a small-bore McGovern surrogate, then he and his publication should expect appropriate treatment, which they will with regularity receive. The Republican Party has been the victim of a barrage of unfounded and unsubstantiated allegations by George McGovern and his partner in mud-slinging, The Washington Post." (83)

Ben Bradlee argues that the next important breakthrough in the case came when James W. McCord issued a statement on 23rd March, 1973. "In the interests of justice and in the interests of restoring faith in the criminal justice system, which faith has been severely damaged in this case, I will state the following to you at this time which I hope may be of help to you in meting out justice in this case. 1. There was political pressure applied to the defendants to plead guilty and remain silent. 2. Perjury occurred during the trial in matters highly material to the very structure, orientation and impact of the government's case, and to the motivation and intent of the defendants. 3. Others involved in the Watergate operation were not identified during the trial, when they could have been by those testifying." (84)

On 30th April 1973, Richard Nixon forced two of his principal advisers H. R. Haldeman and John Ehrlichman, to resign. Richard Nixon later recalled that sacking Haldeman was "the hardest decision I had ever made." Ehrlichman did not take the decision as well as Haldeman. He had been telling Nixon for some time that he should resign. He told Nixon that day: "I have done nothing that was without your implied or direct approval." (85) A third adviser, John Dean, refused to go and was sacked.

Ben Bradlee was seen as partly responsible for these resignations. In his autobiography he pointed out: "April 1973 was probably the worst month ever for the Nixon White House... Magruder told the grand jury that Dean and Mitchell had approved the Watergate bugging. Acting FBI director Patrick Gray was revealed to have destroyed two folders taken from Howard Hunt's safe in the White House, immediately after the Watergate break-in, and was forced to resign in humiliation... A Wall Street Journal poll showed that a majority of Americans now believed that the president knew about the cover-up." (86)

On 12th April, The Washington Post won a Pulitzer Prize for its Watergate reporting. Eight days later, John Dean issued a statement making it clear that he was unwilling to be a "scapegoat in the Watergate case". He told his lawyer: "I've been thinking that maybe I should go public with something. Maybe I should let them know I'm not going to take this lying down." (87) When Dean testified on 25th June, 1973 before the Senate Committee investigating Watergate, he claimed that Richard Nixon participated in the cover-up. He also confirmed that Nixon had tape-recordings of meetings where these issues were discussed. (88)

Ben Bradlee points out that Bob Woodward found out that Alexander Butterfield was in charge of Nixon's "internal security" and suspected he had been responsible for arranging Nixon's secret recordings. He gave this information to "an investigator on the Ervin Committee". He passed this to Samuel Dash and Butterfield was interviewed on 13th July. Late that night, Woodward received a telephone call from the investigator: "We interviewed Butterfield. He told the whole story. Nixon bugged himself." Bradlee commented in his memoirs: "The death knell of Richard Nixon was tolling." (89)

The Special Prosecutor now demanded access to these tape-recordings. At first Nixon refused. Carl Bernstein began calling sources at the White House: "Four of them said they had learned that the tapes were of poor quality, that there were gaps in some conversations. But they did not know whether these had been caused by erasures. Ron Ziegler told Bernstein there were no gaps or erasures in the tapes. However, on 21st November, Nixon's lawyers admitted that one of the tapes had a gap of over 18 minutes. (90)

The Supreme Court ruled against Nixon and members of the Senate began calling for him to be impeached, he changed his mind. However, some tapes were missing while others contained important gaps. Under extreme pressure, Nixon supplied tape scripts of the missing tapes. It was now clear that Nixon had been involved in the cover-up and members of the Senate began to call for his impeachment. On 9th August, 1974, Richard Nixon became the first President of the United States to resign from office. Nixon was granted a pardon but other members of his staff involved in helping in his deception were imprisoned.

Ben Bradlee received a lot of the credit for bringing down Richard Nixon. Katharine Graham, the publisher of the The Washington Post, explained the role played by Bradlee: "Woodward and Bernstein clearly were the key reporters on the story - so much so that we began to refer to them collectively as Woodstein - but the cast of characters at the Washington Post who contributed to the story from its inception was considerable. As executive editor, Ben was the classic leader at whose desk the buck of responsibility stopped. He set the ground rules - pushing, pushing, pushing, not so subtly asking everyone to take one more step, relentlessly pursuing the story in the face of persistent accusations against us and a concerted campaign of intimidation." (91)

Christopher Reed has pointed out: "Watergate hurt Washington, but was also cited as proof that its political system worked – eventually. It made stars of the two reporters and thrust newspaper journalism into a heroic new mould.... Bradlee embraced the truth theme fervently ... and taught courses on truth at Harvard and Georgetown universities... It was a curious stance for someone who spent many years undercover as a counter-espionage informant, a government propagandist, and unofficial asset of the Central Intelligence Agency. It started publicly enough with his Pacific war posting as a navy destroyer intelligence officer. Thereafter it became much more more clandestine." (92)

James Truitt and Ben Bradlee

James Truitt gave an interview to the National Enquirer that was published on 23rd February, 1976, with the headline, "Former Vice President of Washington Post Reveals... JFK 2-Year White House Romance". Truitt told the newspaper that Mary Pinchot Meyer was having an affair with John F. Kennedy. He also claimed that Mary had told them that she was keeping an account of this relationship in her diary. Truitt added that the diary had been removed by Ben Bradlee and James Jesus Angleton. (93)

The newspaper sent a journalist to interview Bradlee about the issues raised by Truitt. According to one eyewitness account, Bradlee "erupted in a shouting rage and had the reporter thrown out of the building". Nina Burleigh claims that it was Watergate that motivated Truitt to give the interview. "Truitt was disgusted that Bradlee was getting credit as a great champion of the First Amendment for exposing Nixon's steamy side in Watergate coverage after having indulgently overlooked Kennedy's hypocrisies." Truitt was also angry that Bradlee had not exposed Kennedy's affair with Mary Pinchot Meyer in his book, Conversations with Kennedy. Truitt had been close to Meyer during this period and had received a considerable amount of information about the relationship. (94)

Ben Bradlee, who had gone on holiday with his new wife, Sally Quinn, gave orders for the Washington Post to ignore the story. However, Harry Rosenfeld, a senior figure at the newspaper, commented, "We're not going to treat ourselves more kindly than we treat others." (95) However, when the article was published it included several interviews with Kennedy's friends who denied he had an affair with Meyer. Kenneth O'Donnell described her as a "lovely lady" but denied that there had been a romance. Timothy Reardon claimed that "nothing like that ever happened at the White House with her or anyone else." (96)

Bradlee and James Jesus Angleton continued to deny the story. Some of Mary's friends knew that the two men were lying about the diary and some spoke anonymously to other newspapers and magazines. Later that month Time Magazine published an article confirming Truitt's story. (97) In an interview with Jay Gourley, Bradlee's former wife, and Mary's sister, Antoinette Pinchot Bradlee admitted that her sister had been having an affair with John F. Kennedy: "It was nothing to be ashamed of. I think Jackie might have suspected it, but she didn't know for sure." (98)

Two journalists, Ron Rosenbaum and Phillip Nobile, decided to carry out their own investigation into the case. After interviewing James Truitt and several other friends of Mary Pinchot Meyer, including the Angletons, they published an article, entitled, "The Curious Aftermath of JFK's Best and Brightest Affair" in the New Times on 9th July, 1976. According to this version, the search for the diary took place on Saturday, 17th October, five days after her murder. As well as Antoinette (Tony) Bradlee, James and Cicely Angleton, Cord Meyer and Anne Chamberlain, were also present. The search party found nothing. (99)

Later that same day, Tony Bradlee was said to have discovered a "locked steel box" in Mary's studio. Inside it was one one of Mary's artist sketchbooks, a number of personal papers and "hundreds of letters". Peter Janney, the author of Mary's Mosaic (2012) points out: "Tony Bradlee later claimed that the presence of a few vague notes written in the sketchbook - allegedly including cryptic references to an affair with the president - persuaded her that she'd found her sister's missing diary. But Mary's artist sketchbook wasn't her real diary. It was just a ruse." The contents of the box were given to Angleton who claimed he burnt the diary. (100)

Deborah Davis and Ben Bradlee

Deborah Davis was working on a book about Katharine Graham and the Washington Post when the National Enquirer was published in 1976. She interviewed James Truitt and several other colleagues who had worked for the newspaper. Davis later wrote: "According to Truitt, Bradlee has forced him out of the paper in a particularly nasty fashion, with accusations of mental incompetence. and now Truitt decides to get back at Bradlee's story... in Conversations with Kennedy, was not the whole story; that Mary Meyer had been Kennedy's lover and that the day of her murder, James Angleton of the CIA searched her apartment and burned her diary." (101)

Davis's book Katharine the Great: Katharine Graham and the Washington Post was published in 1979 by Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. Davis covered the murder of Mary Pinchot Meyer and commented on Bradlee being unwilling to talk about the matter. However, what really upset Bradlee was her claim that he was involved in Operation Mockingbird, the CIA's attempt to control the media.

In an interview Davis gave to Kenn Thomas of Steamshovel Press in 1992 she pointed out that it was Bradlee's work with United States Information Agency in Paris that was the main cause of the controversy. "It was the propaganda arm of the embassy. They produced propaganda that was then disseminated by the CIA all over Europe. They planted newspaper stories. They had a lot of reporters on their payrolls. They routinely would produce stories out of the embassy and give them to these reporters and they would appear in the papers in Europe... I published the first book just saying that he worked for USIE and that this agency produced propaganda for the CIA. He went totally crazy after the book came out. One person who knew him told me then that he was going all up and down the East Coast having lunch with every editor he could think of saying that it was not true, he did not produce any propaganda. And he attacked me viciously and he said that I had falsely accused him of being a CIA agent. And the reaction was totally out of proportion to what I had said." (102)

As well as having conversations with other editors, Ben Bradlee, contacted William Jovanovich and threatened legal action against the publisher. Bradlee later admitted: "I wrote a letter to Davis's editor pointing out thirty-nine errors concerning the thirty-nine references to me." (103) Just six weeks after the book's release, over 20,000 copies were recalled and shredded even though it had already been nominated for an American Book Award. (104) As A. J. Liebling has pointed out, "freedom of the press is guaranteed only to those who own one".

In 1987 Katharine the Great: Katharine Graham and the Washington Post was published by Zenith Press. As the publisher pointed out: "This new, much-expanded and updated edition includes every word of the original plus new material on the post-Watergate years as well as documentary proof of Ms. Davis's revelations about Post editor Ben Bradlee. Katharine the Great covers many of the major issues and characters of 20th century Washington. On a personal level, it includes the stark portrayal of the unravelling of Katharine's husband Phil and an intimate view of the heights of power to which America's most powerful woman has risen since Watergate." Despite the so-called "thirty-nine errors" Bradlee made no effort to sue Davis or the publisher.

Janet Cooke

Janet Cooke, was a young reporter employed by the Washington Post. Ben Bradlee described her as a "beautiful black woman with dramatic flair and vitality, and an extraordinary talent for writing". (105) Cooke published an article on 28th September, 1980 about a young black boy who lived in Washington. "Jimmy is 8 years old and a third generation heroin addict, a precocious little boy with sandy hair, velvety brown eyes and needle marks freckling the baby-smooth skin of his thin brown arms. He nestles in a large, beige reclining chair in the living room of his comfortably furnished home in Southeast Washington. There is an almost cherubic expression on his small, round face as he talks about life - clothes, money, the Baltimore Orioles, and heroin. He has been an addict since the age of 5." (106)

The article created a great deal of controversy. Marion Barry, then mayor of the city an all-out police search for the boy, which was unsuccessful. Barry claimed that the boy had died of an heroin overdose. Courtland Milloy, a black reporter on the newspaper, told the city editor, Milton Coleman, said he had doubts about the story. Coleman dismissed his views, telling others that he thought Milloy was jealous. Bob Woodward, now the assistant managing editor of the newspaper, submitted the story for the Pulitzer Prize. Cooke was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Feature Writing on 13th April 1981.

The Toledo Blade, a newspaper where Cooke had previously worked, published an article suggesting that she had lied to them about her past and that her academic credentials were inflated. When they realized that Cooke had provided a false résumé, Bradlee and his editors interrogated her and extracted a confession. The newspaper's ombudsman, Bill Green, was asked to investigate and report how the incident could have happened. "This was the biggest assignment ever given to the in-house reader’s representative. Mr. Bradlee had created the position in 1970, making The Post the first major paper to employ an independent, in-house critic. Green produced a detailed, embarrassing report about a newsroom where the urge for journalistic impact overrode several experienced reporters’ doubts about Jimmy’s existence." (107)

Ben Bradlee - A Good Life

Bradlee retired as executive editor of the Washington Post in 1991, but continued as a vice president of the company. In 1995 he published his memoirs, A Good Life: Newspapering and Other Adventures. In the book he confessed that he had indeed, like Deborah Davis had said, worked for Office of U.S. Information and Educational Exchange and had been involved in distributing CIA propaganda. He also admitted that Davis was right when she said that Robert Thayer, the CIA station chief in Paris, had paid him money to pay for travelling expenses. Bradlee described how "he (Thayer) reached nonchalantly into the bottom drawer of his desk and fished out enough francs to fly me to the moon." (108)

However, the most surprising confession was that he had lied during the trial of Raymond Crump, the man accused of killing Mary Pinchot Meyer. Bradlee admitted in the book that he had searched for Meyer's diary with James Jesus Angleton: "We (Bradlee and his wife) asked him (Angleton) how he'd gotten into the house, and he shuffled his feet. (Later, we learned that one of Jim's nicknames inside the agency was 'the Locksmith,' and that he was known as a man who could pick his way into any house in town.) We felt his presence was odd, to say the least, but took him at his word, and with him we searched Mary's house thoroughly. Without success. We found no diary. Later that day, we realized that we hadn't looked for the diary in Mary's studio, which was directly across a dead-end driveway from the garden behind our house. We had no key, but I got a few tools to remove the simple padlock, and we walked toward the studio, only to run into Jim Angleton again, this time actually in the process of picking the padlock. He would have been red-faced, if his face could have gotten red, and he left almost without a word. I unscrewed the hinge, and we entered the studio." (109) However, according to Ron Rosenbaum, when he interviewed Angleton, he described Bradlee as a liar and denied he had ever been in Mary's studio. (110)

Bradlee claims that his wife found the diary in a later search: "Much has been written about this diary-most of it wrong since its existence was first reported. Tony took it to our house, and we read it later that night. It was small (about 6" x 8") with fifty to sixty pages, most of them filled with paint swatches, and descriptions of how the colors were created and what they were created for. On a few pages, maybe ten in all, in the same handwriting but different pen, phrases described a love affair, and after reading only a few phrases it was clear that the lover had been the President of the United States, though his name was never mentioned. To say we were stunned doesn't begin to describe our reactions. Tony, especially, felt betrayed, both by Kennedy and by Mary." (111) It has been claimed that the Bradlee's also found love letters sent by Kennedy to Meyer and these were destroyed. (112)

The following day Antoinette Pinchot Bradlee gave the diary to Angleton and expected him to destroy it: "But it turned out that Angleton did not destroy the document, for whatever perverse, or perverted, reasons. We didn't learn this until some years later, when Tony asked him pointblank how he had destroyed it. When he admitted he had not destroyed it, she demanded that he give it back, and when he did, she burned it, with a friend as witness. None of us has any idea what Angleton did with the diary while it was in his possession, nor why he failed to follow Mary and Tony's instructions." (113)

After the publication of his book, The Good Life (1995), Cicely Angleton and Anne Truitt wrote a letter to the New York Times Book Review to "correct what in our opinion is an error" in Bradlee's autobiography: "This error occurs in Mr. Bradlee's account of the discovery and disposition of Mary Pinchot Meyer's personal diary. The fact is that Mary Meyer asked Anne Truitt to make sure that in the event of anything happening to Mary while Anne was in Japan, James Angleton take this diary into his safekeeping. When she learned that Mary had been killed, Anne Truitt telephoned person-to-person from Tokyo for James Angleton. She found him at Mr. Bradlee's house, where Angleton and his wife, Cicely had been asked to come following the murder. In the phone call, relaying Mary Meyer's specific instructions, Anne Truitt told Angleton for the first time, that there was a diary; and in accordance with Mary Meyer's explicit request, Anne Truitt asked Angleton to search for and take charge of the diary." (114)

Peter Janney, the author of Mary's Mosaic (2012) has questioned this account of events provided by Bradlee. "How could Bradlee's CIA friend have known 'just after lunch' that the murdered woman was Mary Meyer when the victim's identity was still unknown to police? Did the caller wonder if the woman was Mary, or did he know it, and if so, how? This distinction is critical, and it goes to the heart of the mystery surrounding Mary Meyer's murder." Janney was away at boarding school at the time but later he talked to his brother about the events that day. "Christopher recalled that during dinner there had been absolutely no mention of Mary Meyer's murder. But sometime after dinner, 'it had to be quarter to eight, if not eight, Dad was sitting at his desk in the den paying bills' when the phone rang his desk.' Christopher was in his bedroom nearby with his door open doing homework. Our mother, he remembered, was in the master bedroom, most likely either reading or working at her desk. 'Dad picked up the phone in the den,' said Christopher. The next thing remembered was hearing our mother, hysterically crying out, 'Oh no! Oh no!' He rushed into the den, wanting to know what happened. 'Mary Meyer has been shot,' he remembered our father saying. Christopher further recollected it had been 'the police' who had called our father cause they couldn't reach Cord, so Dad was next on the list, something like that.' Both parents were upset, Christopher recalled. "Dad was more calm. Mom was more hysterical, but that was the first they'd heard about it." (115)

At the trial of Raymond Crump, the man accused of killing Mary Pinchot Meyer, Bradlee was the first witness called to the stand, Alfred L. Hantman, the chief prosecutor, asked him under oath, what he found when he searched Mary's studio. "Now besides the usual articles of Mrs. Meyer's avocation, did you find there any other articles of her personal property?" Bradlee replied that he found a pocketbook, keys, wallet, cosmetics, and pencils. He did not tell the court that he found a diary that he had passed on to James Jesus Angleton. (116)

On 2nd December, 2011, The Washington Post published a letter from Angleton's children. They also questioned the account provided by Ben Bradlee: "Anne Truitt, a friend of Tony Bradlee and Bradlee's sister, Mary Meyer, was abroad when Meyer was killed in the District. Truitt called Bradlee and said that Meyer had asked her to request that Angleton retrieve mid burn certain pages of her diary if anything happened to her. James and Cicely Angleton were with Ben and Tony Bradlee at the Bradlees' home when Tony Bradlee received the call. Cicely, our mother, told her daughter Guru Sangat Khalsa, "We all went to Mary's house together." She said there was no break-in because the Bradlees had a key. The diary was not found at that time. Later, Tony Bradlee found it and gave it to James Angleton. He burned the pages that Meyer had asked to be burned and put the rest in a safe. Years later, he gave the rest of the diary to Bradlee at her request." (117)

Some researchers have questioned this account. Anne Truitt knew that Mary Pinchot Meyer was highly critical of the CIA covert activities. James Jesus Angleton would have been the last one Mary would have wanted to know about the diary. Peter Janney, the author of Mary's Mosaic (2012) has argued that his research into the case suggests that it is highly unlikely that the Angleton's children story is true: "Is it now to be believed not only that Mary Meyer entrusted the safekeeping of her diary to Jim Angleton, but that she had also specifically instructed him to 'burn certain pages of her diary if anything happened to her'? Nothing could be further from the truth... It is not known (nor likely ever will be) how Angleton twisted the arm of Anne Truitt to declare that on the night of Mary's murder she should call the Bradlees and inform them that such a diary existed and that Mary had told her to make sure Angleton took charge of it, should anything happen to her. The answer to the question of who called the Truitts in Tokyo to inform them of Mary's demise now becomes more obvious: It was Angleton himself." (118)

David Talbot has argued that Ben Bradlee's account in his book "left more unexplained than answered". Talbot interviewed Bradlee about this issue in 2004. "He denied that the diary contained any secrets about the CIA or other revealing information, beyond the passages about her romance with JFK." Bradlee was more interested in explaining the role of James Jesus Angleton. He claimed that his break-in was possibly connected to his amorous obsession with Mary Pinchot Meyer. "I thought Jim was just like a lot of men, who had a crush on Mary. Although the idea of him as a lover just stretches my imagination, especially for Mary, because she was an extremely attractive woman. And he was so weird! He looked odd, he was off in the clouds somewhere. He was always mulling over some conspiracy when he wasn't working on his orchids. It was hard to have a conversation with him. I bet there are still twelve copies of Mary's diary in the CIA somewhere." (119)

Ben Bradlee and the Assassination of JFK

In 1963, Ben Bradlee was very close to John F. Kennedy. However, in his book, The Good Life (1995), he shows no interest in investigating the murder of his friend and does not even include the name of Lee Harvey Oswald. Nor does he mention the Warren Commission Report. It is rather strange that the man so closely associated with investigative journalism in the 20th Century, showed no interest in researching the case. The same is also true of the murder of his sister-in-law, Mary Pinchot Meyer.

Bradlee's lack of interest in the case was investigated by Robert Blair Kaiser in an article in Rolling Stone. Kaiser points out that the The Washington Post failure to commit investigative resources to the case was "especially puzzling" because of the newspaper's "courageous handling of Watergate and the intimate friendship Bradlee had with President Kennedy." When he asked Bradlee to explain his lack of interest in the case, he replied "I've been up to my ass in lunatics... Unless you can find someone who wants to devote his life to the case, forget it." (120)

While researching his book, Brothers: The Hidden History of the Kennedy Years (2007) David Talbot went to interview Bradlee about the assassination. Talbot told Bradlee that his research showed that on hearing of his brother's death, Robert F. Kennedy "immediately suspected the CIA and its henchmen in the Mafia and Cuban exile world." Talbot reports that Bradlee did not seem surprised: "Jesus, if it were your brother... I mean if I were Bobby, I would certainly have taken a look at that possibility... I've always wondered whether my reaction to all of that was not influenced by sort of a total distaste for the possibility that (Jack) had been assassinated by..." Talbot points out that he did not finish the sentence, but the rest was clear: "by his own government". (121)

Benjamin Bradlee, who suffered from Alzheimer's and dementia, died on 21st October, 2014.

Primary Sources

(1) Deborah Davis, Katharine the Great (1979)

Nineteen fifty-six. Ben Bradlee, recently remarried, is a European correspondent for Newsweek. He left the embassy for Newsweek in 1953, a year before CIA director Allen Duller authorized one of his most skilled and fanatical agents, former OSS operative James Angleton, to set up a counterintelligence staff. As chief of counterintelligence, Angleton has become the liaison for all Allied intelligence and has been given authority over the sensitive Israeli desk, through which the CIA is receiving 80 percent of its information on the KGB. Bradlee is in a position to help Angleton with the Israelis in Paris, and they are connected in other ways as well: Bradlee's wife, Tony Pinchot, Vassar '44, and her sister Mary Pinchot Meyer, Vassar '42, are close friends with Cicely d'Autremont, Vassar '44, who married James Angleton when she was a junior, the year he graduated from Harvard Law School and was recruited into the OSS by one of his former professors at Yale.

Also at Harvard in 1943, as undergraduates, were Bradlee and a man named Richard Ober, who will become Angleton's chief counterintelligence deputy and will work with him in Europe and Washington throughout the fifties, sixties, and early seventies. Both Bradlee and Ober were members of the class of '44 but finished early to serve in the war; both received degrees with the class of '43. Ober went into the OSS and became a liaison with the anti-Fascist underground in Nazi-occupied countries; Bradlee joined naval intelligence, was made a combat communications officer, and handled classified and coded cables on a destroyer in the South Pacific. He then worked for six months as a clerk in the New York office of the American Civil Liberties Union, an organization that promotes various progressive causes, including conscientious objection to war. This job, so out of character for the young patriot, may or may not have been an intelligence assignment.

In 1956 Ben and Tony Bradlee are part of a community of Americans who have remained in Paris after having been trained in intelligence during the war or in propaganda at the Economic Cooperation Administration. Many have now addressed themselves to fighting communism, a less visible but more invidious enemy than nazism had been. Some of them, like Bradlee, are journalists who write from the Cold War point of view; some are intelligence operatives who travel between Washington and Paris, London, and Rome. In Washington, at Philip Graham's salon, they plan and philosophize; in foreign cities, they do the work of keeping European communism in check.

Bradlee's childhood friend Richard Helms is part of this group. He has written portions of the National Security Act of 1947, a set of laws creating the Central Intelligence Agency and the National Security Agency, the latter to support the CIA with research into codes and electronic communications. Helms is the agency's chief expert on espionage; his agents penetrate the government of the Soviet Union and leftist political parties throughout Europe, South America, Africa, and Asia.

Angleton and Ober are counterintelligence, and run agents from Washington and Paris who do exactly the opposite: they prevent spies from penetrating American embassies, the State Department, the CIA itself. Head of the third activity, covert operations, is Phil Graham's compatriot Frank Wisner, the father of MOCKINGBIRD, whose principal operative is a man named Cord Meyer, Jr.

(2) Ben Bradlee, The Good Life (1995)

On a Saturday morning I went to my immediate boss, the embassy's public affairs officer, Bill Tyler, for help. Since we couldn't get any help from Washington, why didn't we send our own man - me, obviously - to New York to read the transcript of the entire Rosenberg Trial (and appeals), return to Paris as quickly as possible, and write a detailed, factual account of the evidence as it was presented, witness by witness, and as it was rebutted, cross-examination by cross-examination? Tyler thought that was a great idea. When could I - should I leave? Right away. Fine, but it was Saturday. The banks were closed and no one had cash for the air fare. "That's all right," said Tyler. "We'll ask Bobby for some francs."