Cord Meyer

Cord Meyer, the son of a senior diplomat, was born on 10th November, 1920. The Meyer family was extremely wealthy and had made its money from sugar in Cuba and from property on Long Island.

Mayer's father fought in the First World War; "My father had served in the First World War as a fighter pilot on the Western Front and my mother as a nurse in army hospitals in France, and, after they married, he had served in the diplomatic service abroad for a few years." (1)

The family settled in New York City. Cord and his twin brother, Quintin, attended private school in Switzerland and then St. Paul's School in New Hampshire. In 1939 Meyer went to Yale University to study literature and philosophy. He found it a rewarding experience: "To me and to many of my classmates, the wide learning and intellectual brilliance of most of our professors was a revelation after the more limited teaching ability we had experienced in our high schools. I felt as if the doors had been thrown open and I had been ushered into a vast and splendid chamber where delicacies had been laid out in such profusion that one hardly knew where to begin." (2)

Cord Meyer became involved in the debate on the Second World War in Europe. He had no sympathy for the American First Committee: "The idealistic wing of the America First movement urged that we stay out of the ancient quarrels of the corrupt continent and concentrate instead on building a just society in our own land that could serve as a model and example to the world. The anti-war writing of the thirties and the history we had been taught of the bloody and inconclusive folly of the First World War led many to support this isolationist position. The interventionists stressed the horrors of the Nazi dictatorship and warned that, if we did not come to England's aid, we would be left alone to face Hitler's conquering armies." (3)

Cord Meyer - Second World War

After graduating in 1942 he joined the US Marines and took part in the invasion of Eniwetok. Cord Meyer later recalled: "We were astonished by the behavior of the Japanese, although we had been amply warned. The sensible thing for the Japanese on Eniwetok to have done would have been to run up a flag of surrender when they first saw our armada of battleships, cruisers, and heavily loaded troopships steam into the lagoon. Among most Western armies, it would have been no disgrace to surrender to such an overwhr.ltning show of force. However, they chose to fight to the last man and to take as many of us with them as they could before they died. With their last bullet, they would commit suicide rather than allow themselves to be captured. If they were wounded they would hide a grenade so that those of us who attempted to help would be blown up with them. Only those most seriously wounded or those stunned into unconsciousness by a shell burst could be taken prisoner. We had a grudging respect for their suicidal bravery." (4)

Meyer was a machine-gun platoon leader and took part in the assault on Guam. On 21st July, 1944, a Japanese grenade was thrown into his foxhole. He was so badly injured that when he was found he was initially declared to be dead. He later wrote about this experience in a short-story published in Atlantic Monthly.: "A great club smashed him in the face. A light grew in his brain to agonizing brightness and then exploded in a roar of sound that was itself like a physical blow. He fell backward and an iron door clashed shut against his eyes. He cried aloud once, as if through the sound the pain that filled him might find an outlet to overflow and diminish. Once more a long, rising moan was drawn from him and he lifted his hands in a futile gesture as though to rip away the mask of agony that clung to his face. Then, even in that extremity, the will to survive asserted itself. Through the fire that seemed to consume him, the knowledge that the enemy must be near-by made him stifle the scream that rose in his throat. If he kept quiet they might leave him for dead, and that was his only hope." (5)

Soon afterwards his twin brother, Quentin, was killed at Okinawa. His war experiences had a dramatic impact on his political views. He later commented: "As we buried our dead I swore to myself that if it was within my power I should see to it that these deaths would not be forgotten or valued lightly. No matter how small a contribution I should happen to make it would be in the right direction." In his journal he wrote: "So then I have discharged my duty in that capacity, but the whole center and axis of my world has changed. I did not realize before how much I had completely discounted the future... I lived in the present and to a certain extent in the past and was assured in my own mind that there was no alternative to the life I led and the decision I had made. Now my duty is not so obvious, and the future full of conflicting alternatives. In the hospital convalescing as I am now, there is not yet the necessity for action. I inhabit temporarily a Lotus Eater's land of eating and sleeping but soon I must start again on that expanding adventure that is every man's life and before me are the most important decisions." (6)

Mary Pinchot Meyer

In the autum of 1944 Cord Meyer met Mary met Mary Pinchot, a journalist working at United Press International. Meyer recorded in his autobiography, Facing Reality: From World Federalism to the CIA (1980): "From Hawaii, I was flown to a hospital in the San Francisco area and finally back to New York City in September of 1944. I lived with my parents and commuted to the Brooklyn Naval Hospital, where I was fitted with a reasonably convincing glass eye. After some minor plastic surgery, I was ready to face the world and began seeing a lot of Mary Pinchot." (7)

Mary Pinchot's biographer points out: "During the long nights the young couple talked for hours. They discussed the catastrophe of war, the meaning of death, and the human capacity for peace. Cord had an intensity that intrigued Mary and the deep seriousness she thought she wanted in a man. He was a literary talent whose writing was already being published in national magazines. He was also a man of action who had emerged from war deeply committed to peace... As Mary watched his face and listened to him talk with an almost religous zeal about the wrongness of war, there was no doubt in her mind that here was a man who had the courage to put his ideals - so similar to her own - into action." (8)

The couple married on 19th April, 1945. Soon afterwards the couple went to San Francisco to attend the conference that established the United Nations. Cord went as an aide to Harold Stassen, whereas Mary, who was working for the North American Newspaper Alliance at the time, was one of the reporters sent to cover this important event. "As the conference got under way, I watched with growing concern the construction of the foundations and scaffolding of the new international organization that was to replace the defunct League of Nations." (9)

Meyer told te New York Times that although the United Nations was a step in the right direction "that the veto power was just another alliance of the great powers and one that would surely lead to another war." Cord proposed that the UN be granted authority to oversee nuclear power installations inside member countries. He also argued that the UN should be given the authority to prevent war and "the armed power to back it up."

Cord Meyer had been shocked by the dropping of the atom bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In an essay published in the New York Times Meyer described the bombb's belittling effect on veterans such as himself: "The pillar of smoke over Japan on August 8 spelled in large letters for all who dared to read, not only the end of that war, but the end of our own security, no matter what our military strength." (10) Cord wrote in his journal: "Talked with Mary of how steadily depressing is our full realization of how little hope there is of avoiding the approaching catastrophe of atomic warfare."(11) The following year Meyer published a short-story about his war experiences, Waves of Darkness. Meyer expressed pacifist views in the book: "The only certain fruit of this insanity will be the rotting bodies upon which the sun will impartially shine tomorrow. Let us throw down these guns that we hate." (12)

For a while Mary Pinchot Meyer worked as an editor for the Atlantic Monthly. Her first child Quentin was born in 1945. After the birth of Michael in 1947 she became a housewife but still managed to attend classes at the Art Students League in New York City. Mary began to take her art more seriously and came into contact with the abstract expressionists working in the city. One of her life drawing classes was taught by a Russian artist named Nahum Tschacbasov, who "encouraged his students to invent freely and examine underlying organic structure." (13)

Like her husband, Mary became an advocate of world government. In May, 1947, Cord Meyer was elected president of the United World Federalists. "My reason for making such an abrupt change in my career was a conviction that the United States, through its atomic monopoly, had for a brief period the opportunity to lead the world toward effective international control of the bomb." (14) Under his leadership, membership of the organization doubled in size. Albert Einstein was one of his most important supporters and personally solicited funds for the organization. Mary wrote for its journal, The United World Federalists.

The family now moved back to Cambridge. Cord was showing signs of becoming disillusioned with the idea of world government. He had experienced problems with members of the Communist Party of the United States who had infiltrated the organizations he had established. He pointed out that in an article in the New Masses condemned "the reactionary utopianism of the world state project" and stated that "by seeking solutions in abstract reason and justice rather than in the actual class forces in society, it (world government) weakens the struggle for progress and strengthens the hand of reaction." (15)

Cord Meyer joins CIA

Mary's third child, Mark, was born in 1950. Soon afterwards Allen W. Dulles made contact with her husband. "Allen Dulles, who was at the time deputy director for plans of the Central Intelligence Agency... He was kind enough to give me more than an hour of his time, and we had a fasinating discussion. In a serious and careful way, he spelled out the nature of the world situation as he saw it and the complex challenge with which we were confronted by Stalin's regime... At the end of the meeting, he made me a firm offer of a job with the Agency at a middlelevel of executive responsibility and assured me that the work would be suited to my abilities and past experience, although for security reasons he could not describe the job in any detail." (16)

Cord Meyer accepted the invitation to join the Central Intelligence Agency. Dulles told Meyer he wanted him to work on a project that was so secret that he could not be told about it until he officially joined the organization. Meyer was to work under Frank Wisner, director of the Office of Policy Coordination (OPC). This became the espionage and counter-intelligence branch of the CIA. Wisner was told to create an organization that concentrated on "propaganda, economic warfare; preventive direct action, including sabotage, anti-sabotage, demolition and evacuation measures; subversion against hostile states, including assistance to underground resistance groups, and support of indigenous anti-Communist elements in threatened countries of the free world." As David Corn, the author of Blond Ghost (1994) pointed out: "The OPC was let loose and frantically moved to slip $1 million in secret funds to pro-American, noncommunist political parties... Under the leadership of Frank Wisner... the OPC grew into... a grand instrument that could... mount operations, rig elections, control newspapers, sway opinion." (17)

Meyer became part of what became known as Operation Mockingbird, a CIA program to influence the mass media. According to Deborah Davis, the author of Katharine the Great: Katharine Graham and the Washington Post (1979) Meyer was Mockingbird's "principal operative". Richard Bissell called Cord Meyer "the creative genius behind convert operations". (18) Davis claims that "By the early 1950s, Wisner had implemented his plan and 'owned' respected members of the New York Times, Newsweek, CBS, and other communications vehicles, plus stringers, four to six hundred in all... Whether the journalists thought of themselves as helpers of the agency or merely as patriots, agreeing to run stories that would benefit their country." (19)

Frank Wisner and the CIA began having trouble with J. Edgar Hoover. He described the Office of Policy Coordination (OPC) as "Wisner's gang of weirdos" and began carrying out investigations into their past. It did not take him long to discover that some of them had been active in left-wing politics in the 1930s. This information was passed to Joseph McCarthy who started making attacks on members of the OPC. Hoover also passed to McCarthy details of an affair that Wisner had with Princess Caradja in Romania during the war. Hoover, claimed that Caradja was a Soviet agent.

McCarthy also began accusing other members of the Georgetown Crowd as being security risks. In August, 1953, Richard Helms, Wisner's deputy at the OPC, told Meyer that Joseph McCarthy had accused him of being a communist. The Federal Bureau of Investigation added to the smear by announcing it was unwilling to give Meyer "security clearance". However, the FBI refused to explain what evidence they had against Meyer. Allen W. Dulles and both came to his defence and refused to permit a FBI interrogation of Meyer. Suspicion also fell on Mary at this time and it was revealed that the FBI had been investigating her activities. Meyer was told "Your wife, Mrs Mary Pinchot Meyer, is alleged to have registered as a member of the American Labor Party of New York in 1944 at which time it was reportedly under extreme left-wing of Communist domination." (20)

It seemed that the FBI objected to Meyer being a member of several liberal groups considered to be subversive by the Justice Department. This included being a member of the National Council on the Arts, where he associated with Norman Thomas, the leader of the Socialist Party and its presidential candidate in 1948. Allen W. Dulles came to Meyer's defence and refused to allow him to be interrogated by the FBI. "I wondered who it was in the FBI who had spent so much time and effort in researching every corner of my past to weave together this tapestry of unrelated incidents designed to prove my disloyalty." (21)

Meyer was eventually cleared of these charges and was allowed to keep his job. J. Edgar Hoover and Joseph McCarthy did not realise what they were taking on. Frank Wisner unleashed Operation Mockingbird on McCarthy. Drew Pearson, Joe Alsop, Jack Anderson, Walter Lippmann and Ed Murrow all went into attack mode and McCarthy was permanently damaged by the press coverage orchestrated by Wisner.

Frances Stonor Saunders has pointed out: "Cord Meyer wasn't red. He wasn't even pink... his alleged crimes dated to the immediate post-war years when Meyer had been a leader of the American Veterans' Committee, a liberal organization designed to offer an alternative to the ultra-conservative American Legion, and a founder of the United World Federalists, which called for world government, and was more utopian than liberal... The episode was to mark Meyer for the rest of his life, and it serves to illustrate one of the great paradoxes of Cold War America: whilst CIA men worked around the clock to defeat Communism, they were being tailed by fellow Americans who claimed to be bent on the same objective. If Juvenal had wondered who was guarding the guards, the question here was more who was slaying the dragon-slayers?" (22)

Mary and Cord Meyer moved to Georgetown. Their friends included Frank Wisner, George Kennan, Dean Acheson, Thomas Braden, Richard Bissell, Desmond FitzGerald, James Jesus Angleton, Joseph Alsop, Tracy Barnes, Philip Graham, Katharine Graham, David Bruce, Ben Bradlee, Antoinette Pinchot Bradlee, James Truitt, Anne Truitt, Clark Clifford, Walt Rostow, Eugene Rostow, Chip Bohlen and Paul Nitze. According to Nina Burleigh, the author of A Very Private Woman (1998): "The Angletons, Truitts, and Meyers grew very close, and they were especially bound together by their mutual interest in art and culture." (23)

Cord Meyer became disillusioned with life in the CIA and in January, 1954, he went to New York City and attempted to get a job in publishing. Although he saw contacts he had made during his covert work with the media (Operation Mockingbird) he was unable to obtain a job with any of the established book publishing firms. "I intend to pursue the search and be out of the government by June... I have been buried long enough in the anonymity of the federal bureaucracy." (24) In the summer of 1954 the Meyer family's golden retriever was hit by a car on the curve of highway near their house and killed. The dog's death worried Cord. He told colleagues at the CIA he was afraid the same thing might happen to one of his children. (25)

In August 1954, Mary Pinchot Meyer and her sister, Antoinette Pinchot Bradlee, went on holiday to Europe. While they were in Paris they met an old friend, Ben Bradlee, who was working for Newsweek. Bradlee later recalled: "The weekend that changed my life forever came in August of 1954, when our friends the Pinchot sisters hit town. Mary Pinchot Meyer, mother of three and wife of Cord Meyer, war hero turned World Federalists president and CIA biggie, and Antoinette Pinchot Pittman, mother of four, wife of Steuart Pittman, a Washington lawyer. They were both members of our Washington crowd - on the last leg of a European tour, to which they had treated themselves after seven years of diapers and dishes." (26) Bradlee fell in love with Antoinette and they later got married.

In the summer of 1954 the Meyers got new neighbours. John F. Kennedy and his wife Jackie Kennedy purchased Hickory Hill, a house several hundred yards from where the Meyers lived. "Soon Mary befriended the senator's dark-haired wife, ten years younger than she. One of the things the two women had in common was that Jackie Kennedy and her sister, Lee Radziwill, had also taken a parent-financed, sisters-only trip to Europe together... Jackie was often left alone. The senator was intensely ambitious and angling for a national nomination in 1956. He was also incorrigible in his skirt-chasing." (27)

In November, 1954, Meyer replaced Thomas Braden as head of International Organizations Division. Meyer began spending a lot of time in Europe. One of Meyer's tasks was to supervise Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty, the United States government broadcasts to Eastern Europe. "I became head of one of the major operating divisions of the Directorate of Plans, with a growing budget and a wide policy mandate under a new National Security Council directive to counter with covert action the political and propaganda offensive that the Soviets had launched through their control of a battery of international front organizations." (28)

Divorce

On 18th December, 1956, Cord Meyer's nine-year-old son, Michael, was hit by a car on the curve of highway near their house and killed: "Mary heard the screech of tires and the screams of her oldest son. She raced down the hill toward the awful scene. The driver who had struck Michael had become hysterical. An ambulance arrived, but it was too late. Mary would for the last time, hold and accompany Michael to the hospital, but not before she paused to comfort the driver who had struck her son, her rare compassion anchored in some deeper dimension." (29)

The tragedy briefly brought the couple together. A year after his son's death, Cord Meyer agreed to leave the family home and begin the separation required for a divorce. He moved into an apartment in Georgetown. In 1958, Mary Pinchot Meyer filed for divorce. In her divorce petition she alleged "extreme cruelty, mental in nature, which seriously injured her health, destroyed her happiness, rendered further cohabitation unendurable and compelled the parties to separate." Cord Meyer was furious at the legal description since he believed himself to be in the right. (30)

International Organizations Division

As head of the International Organizations Division, Meyer oversaw the funding of groups such as the National Student Association, Communications Workers of America, the American Newspaper Guild, the United Auto Workers, National Council of Churches, the African-American Institute and the National Education Association. He also provided the money for publishing the journal, Encounter. Meyer also worked closely with anti-Communist leaders of the trade union movement such as George Meany of the Congress for Industrial Organization and the American Federation of Labor. (31) According to Frank Church, Meyer ran a division which constituted the greatest single concentration of covert political and propaganda activities of the by now octopus-like CIA. (32)

Meyer's main work was with the Congress of Cultural Freedom (CCF). It has been argued by Frances Stonor Saunders that the CCF was funded by the CIA as they wanted to promote what they called the Non-Communist Left (NCL). (33) Arthur Schlesinger later recalled that the NCL was supported by leading establishment figures such as Chip Bohlen, Isaiah Berlin, Averell Harriman and George Kennan: "We all felt that democratic socialism was the most effective bulwark against totalitarianism. This became an undercurrent - or even undercover - theme of American foreign policy during the period."

In October, 1955, Michael Josselson, aged forty-seven, suffered a major heart attack. Cord Meyer decided to send recent CIA recruit, John Clinton Hunt, to work as his assistant to "lighten the load". In order to provide cover for Hunt, he officially applied for the job. Interviewed by Josselson in February 1956, Hunt was formally appointed to the Congress Secretariat shortly afterwards. (34)

President Dwight Eisenhower gave the International Organizations Division his full support: "As long as it remains national policy, another important requirement is an aggressive covert psychological, political and paramilitary organization more effective, more unique, and it necessary, more ruthless than that employed by the enemy. No, one should be permitted to stand in the way of the prompt, efficient, and secure accomplishment of this mission. It is now clear that we are facing an implacable enemy whose avowed objective is world domination by whatever means and at whatever cost. There are no rules in such a game. Hitherto acceptable norms of human conduct do not apply. If the U.S. Is to survive, longstanding American concepts of fair play' must be reconsidered... It may become necessary that the American people be made acqquainted with, understand and support this fundamentally repugnant philosophy." (35)

Frances Stonor Saunders, the author of Who Paid the Piper: The CIA and the Cultural Cold War? (1999) has argued: "During the height of the Cold War, the US government committed vast resources to a secret programme of cultural propaganda in western Europe. A central feature of this programme was to advance the claim that it did not exist. It was managed, in great secrecy, by America's espionage arm, the Central Intelligence Agency... At its peak, the Congress for Cultural Freedom had offices in thirty-five countries, employed dozens of personnel, published over twenty prestige magazines, held art exhibitions, owned a news and features service, organized high-profile international conferences, and rewarded musicians and artists with prizes and public performances. Its mission was to nudge the intelligentsia of western Europe away from its lingering fascination with Marxism and Communism... Membership of this consortium included an assorted group of former radicals and leftist intellectuals whose faith in Marxism and Communism had been shattered by evidence of Stalinist totalitarianism." (36)

Cord Meyer was in charge of financing the various organizations established to fight communism. In 1955 the CIA began to cut its subsidies. In a letter to Arthur Schlesinger, in response for more help, Meyer wrote: "We certainly don't plan on any continuing large scale assistance, and the single grant recently made was provided as the result of an urgent request directly from Sidney Hook and indirectly from Norman Thomas. Our hope is that the breathing space provided by the assistance can be used by those gentlemen, yourself, and the other sensible ones to reconstitute the Executive Committee and draft an intelligent program... If this reconstitution of the leadership proves impossible we then, I think, will have to face the necessity of allowing the Committee to die a natural death, although I think this course would result in unhappy repercussions abroad." (37)

As chief of the CIA's International Organizations Division, Meyer had regular meetings with President John F. Kennedy and his staff. On 18th October, 1961, Kennedy consulted Meyer about the possibility of replacing Allen W. Dulles with John McCone. In his journal he reported that Kennedy was "much more serious and less arrogant than I'd known him before." He added that Kennedy "still yearns for a respect that eludes him from such as myself." It is assumed that Cord was involved in the plot to assassinate Fidel Castro but so far no documents have been released to confirm this. Cord also met Robert Kennedy several times after the failed Bay of Pigs operation.

In 1961 James Jesus Angleton asked Ben Bradlee to suggest to John F. Kennedy that Meyer should become ambassador to Guatemala. Bradlee, who disliked Meyer, refused. Bradlee later claimed that he did not respond to this request because he knew that Kennedy would reject the idea. Meyer also asked Charles L. Bartlett, another journalist friend of Kennedy to suggest he should be given a political appointment. Bartlett did as requested but reported back that "due to some incident that occured at the U.N. conference in San Francisco in 1945 there was no possibility".

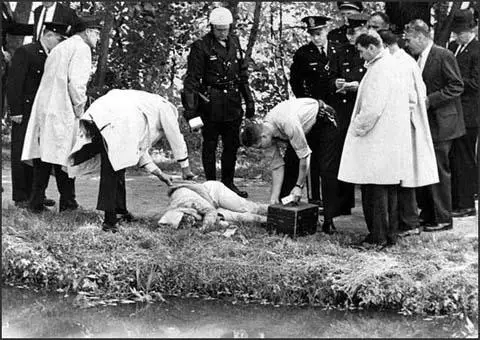

Murder of Mary Pinchot Meyer

On 12th October, 1964, Mary Pinchot Meyer was shot dead as she walked along the Chesapeake and Ohio towpath in Georgetown. Henry Wiggins, a car mechanic, was working on a vehicle on Canal Road, when he heard a woman shout out: "Someone help me, someone help me". He then heard two gunshots. Wiggins ran to the edge of the wall overlooking the towpath. He later told police he saw "a black man in a light jacket, dark slacks, and a dark cap standing over the body of a white woman." (38)

Mary appeared to be killed by a professional hitman. The first bullet was fired at the back of the head. She did not die straight away. A second shot was fired into the heart. The evidence suggests that in both cases, the gun was virtually touching Mary’s body when it was fired. As the FBI expert testified, the “dark haloes on the skin around both entry wounds suggested they had been fired at close-range, possibly point-blank”. (39)

Ben Bradlee points out that the first he heard of the death of Mary Pinchot Meyer was when he received a phone-call from Wistar Janney, his friend who worked for the CIA: "My friend Wistar Janney called to ask if I had been listening to the radio. It was just after lunch, and of course I had not. Next he asked if I knew where Mary was, and of course I didn't. Someone had been murdered on the towpath, he said, and from the radio description it sounded like Mary. I raced home. Tony was coping by worrying about children, hers and Mary's, and about her mother, who was seventy-one years old, living alone in New York. We asked Anne Chamberlin, Mary's college roommate, to go to New York and bring Ruth to us. When Ann was well on her way, I was delegated to break the news to Ruth on the telephone. I can't remember that conversation. I was so scared for her, for my family, and for what was happening to our world. Next, the police told us, someone would have to identify Mary's body in the morgue, and since Mary and her husband, Cord Meyer, were separated, I drew that straw too." (40)

Peter Janney, the author of Mary's Mosaic (2012) has questioned this account of events provided by Bradlee. "How could Bradlee's CIA friend have known 'just after lunch' that the murdered woman was Mary Meyer when the victim's identity was still unknown to police? Did the caller wonder if the woman was Mary, or did he know it, and if so, how? This distinction is critical, and it goes to the heart of the mystery surrounding Mary Meyer's murder." Janney even questions if it really was his father who phoned Bradlee. He points out that Wistar Janney had died a year before Bradlee published his account of events. (41)

That night Antoinette Pinchot Bradlee received a telephone call from Mary's best friend, Anne Truitt, an artist living in Tokyo. She told her that it "was a matter of some urgency that she found Mary's diary before the police got to it and her private life became a matter of public record". (42) Mary had apparently told Anne that "if anything ever happened to me" you must take possession of my "private diary". Ben Bradlee explains in The Good Life (1995): "We didn't start looking until the next morning, when Tony and I walked around the corner a few blocks to Mary's house. It was locked, as we had expected, but when we got inside, we found Jim Angleton, and to our complete surprise he told us he, too, was looking for Mary's diary." (43)

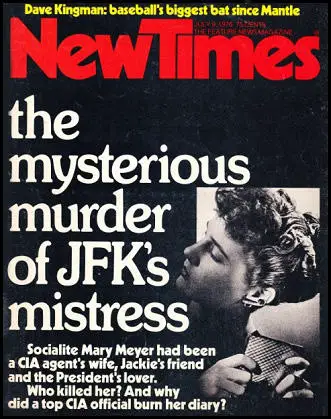

James Jesus Angleton later claimed that he had also received a telephone call from Anne Truitt. His wife, Cicely d'Autremont Angleton, confirmed this in an interview given to Nina Burleigh. (44) However, an article by Ron Rosenbaum and Phillip Nobile, in the New Times on 9th July, 1976, gives a different version of events with the Angleton's arriving at Mary's house that evening to attend a poetry reading and that at this stage they did not know she was dead. (45)

Joseph Trento, the author of Secret History of the CIA (2001), has pointed out: "Cicely Angleton called her husband at work to ask him to check on a radio report she had heard that a woman had been shot to death along the old Chesapeake and Ohio towpath in Georgetown. Walking along that towpath, which ran near her home, was Mary Meyer's favorite exercise, and Cicely, knowing her routine, was worried. James Angleton dismissed his wife's worry, pointing out that there was no reason to suppose the dead woman was Mary - many people walked along the towpath. When the Angletons arrived at Mary Meyer's house that evening, she was not home. A phone call to her answering service proved that Cicely's anxiety had not been misplaced: Their friend had been murdered that afternoon." (46)

Mary appeared to be killed by a professional hitman just after midday. The first bullet was fired at the back of the head. She did not die straight away and her screams were heard by several people. While she was down on the ground and probably in severe shock from the head wound, the gunman shot her in the back. The bullet severed the aorta, which carries blood to the heart, and came out of her chest on the other side. (47) The evidence suggests that in both cases, the gun was virtually touching Mary’s body when it was fired. As the FBI expert testified, the “dark haloes on the skin around both entry wounds suggested they had been fired at close-range, possibly point-blank”. (48)

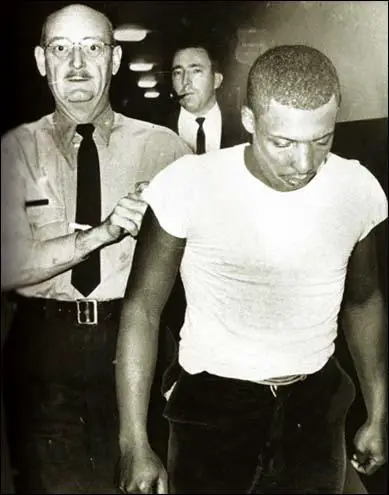

Soon afterwards Raymond Crump, a black man, was found not far from the murder scene. He was arrested and charged with Mary's murder. Police tests were unable to show that Crump had fired the .38 caliber Smith and Wesson gun. There were no trace of nitrates on his hands or clothes. Despite an extensive search of the area no gun could be found. This included a two day search of the tow path by 40 police officers. The police also drained the canal near to the murder scene. Police scuba divers searched the waters away from where Mary was killed. However, no gun could be found. Nor could the prosecution find any link between Crump and any Smith and Wesson gun. (49)

The Trial of Raymond Crump

The trial of Crump began on 19th July, 1965. Crump’s lawyer, Dovey Roundtree, was convinced of his innocence. A civil rights lawyer who defended him for free, she argued that Crump was so timid and feeble-minded that if he had been guilty he would have confessed everything while being interrogated by the police. "Dovey Roundtree would stake her professional life on defending a victimized, dirt-poor young black man. For Roundtree, it wasn't just the life and future of one man that was at stake. She believed Crump was being conveniently scapegoated." (50) Roundtree later recalled: "I was caught up in civil rights, heart, body, and soul, but I felt law was one vehicle that would bring remedy." (51)

None of the newspaper reports of the trial identified the true work of her former husband, Cord Meyer. He was described as a government official or an author. A large number of journalists knew that Meyer had been married to a senior CIA officer. They also knew that she had been having an affair with John F. Kennedy. None of this was reported. In fact, the judge, ruled that the private life of Mary Meyer could not be mentioned in court. (52)

The trial judge was Howard Corcoran. He was the brother of Tommy Corcoran, a close friend of Lyndon B. Johnson. Corcoran had been appointed by Johnson soon after he became president. It is generally acknowledged that Corcoran was under Johnson’s control. His decision to insist that Mary’s private life should not be mentioned in court was very important in disguising the possible motive for the murder. (53) This information was also kept from Crump’s lawyer, Dovey Roundtree. Although she attempted to investigate Mary's background she found little information about her: "It was as if she existed only on the towpath on the day she was murdered." Peter Janney argues: "There were rumblings swirling all over Washington and elsewhere about CIA involvement in President Kennedy's assassination, and Corcoran likely sought to steer clear of any mention of the Agency altogether." (54)

Bradlee was the first witness called to the stand, Alfred L. Hantman, the chief prosecutor, asked him under oath, what he found when he searched Mary's studio. "Now besides the usual articles of Mrs. Meyer's avocation, did you find there any other articles of her personal property?" Bradlee replied that he found a pocketbook, keys, wallet, cosmetics, and pencils. He did not tell the court that he found a diary that he had passed on to James Jesus Angleton. (55)

During the trial Wiggins was unable to positively identify Raymond Crump as the man standing over Meyer's body. The prosecution was also handicapped by the fact that the police had been unable to find the murder weapon at the scene of the crime or to provide a credible motive for the crime. In her closing argument, Dovey Roundtree, had asked why the police had been unable to find the murder weapon? "She answered her own question: Obviously the gun was nowhere near the towpath if those experts could not locate it. The real killer had walked out of the park with it." (56) On 29th July, 1965, Crump was acquitted of murdering Mary Meyer. The case remains unsolved.

Exposed by Ramparts

Warren Hinckle, the editor of a small-left-wing journal, Rapparts, met a man by the name of Michael Wood, in January, 1967, at the New York's Algonquin Hotel. The meeting had been arranged by a public relations executive Marc Stone (the brother of I. F. Stone). Wood told Hinckle that the National Student Association (NSA) was receiving funding from the CIA. "The CIA during the McCarthyite fifties became a political sanctuary for achievement-oriented liberals. While the ADA-types and the Arthur Schlesinger model liberal kewpie dolls battled fascism by protecting their right flank with domestic Red-baiting and Cold War one-upmanship, the Ivy League delinquents who fled to the CIA-liberal lawyers, business-men, academics, games-playing craftsmen - hatched a master plan of Germanic ambition that entailed nothing less than clandestine political control of the international operations of all important American professional and cultural organization: journalists, educators, jurists, businessmen, et al. The standing CIA subsidy to the National Student Association was one slice of a very complex pie." (57)

Desmond FitzGerald, head of the Directorate for Plans, discovered that Hinckle had the story. FitzGerald ordered Edgar Applewhite to organize a campaign against the magazine. Applewhite later told Evan Thomas for his book, The Very Best Men: "I had all sorts of dirty tricks to hurt their circulation and financing. The people running Ramparts were vulnerable to blackmail. We had awful things in mind, some of which we carried off.... We were not the least inhibited by the fact that the CIA had no internal security role in the United States." (58)

Hinckle even had doubts about publishing the story. Sol Stern, who was writing the article for Rapparts, "advanced the intriguing contention that such a disclosure would be damaging to the enlightened men of the liberal internationalistic wing of the CIA who were willing to provide clandestine money to domestic progressive causes." Hinckle did go ahead with the story and took full-page advertisements in the Tuesday editions of the New York Times and Washington Post: "In its March issue, Ramparts magazine will document how the CIA has infiltrated and subverted the world of American student leaders, over the past fifteen years." For its exposé of the CIA, the journal received the George Polk Memorial Award for Excellence in Journalism and was praised for its "explosive revival of the great muckraking tradition." (59)

The magazine's findings were swiftly picked up in national newspapers, and a large number of articles appeared that detailed the work of Cord Meyer and his team. The most damaging was an article written by Meyer's former boss, Thomas Braden, that appeared in the Saturday Evening Post on 20th May, 1967. He defended what the CIA had been doing by explaining the problem that faced the organisation: "When I went to Washington in 1950 as assistant to Allen W. Dulles, then deputy director to CIA chief Walter Bedell Smith, the agency was three years old. It had been organized. like the State Department, along geographical lines, with a Far Eastern Division, a Western European Division, etc. It seemed to me that this organization was not capable of defending the United States against a new and extraordinarily successful weapon. The weapon was the international Communist front."

Braden rejected the idea that the CIA should have been under the control of Congress: "As for the theory advanced by the editorial writers that there ought to have been a Government foundation devoted to helping good causes agreed upon by Congress - this may seem sound, but it wouldn't work for a minute. Does anyone really think that congressmen would foster a foreign tour by an artist who has or has had left-wing connections? And imagine the scuffles that would break out as congressmen fought over money to subsidize the organizations in their home districts. Back in the early 1950's, when the cold war was really hot, the idea that Congress would have approved many of our projects was about as likely as the John Birch Society's approving Medicare." (60)

Later that year Cord Meyer became assistant deputy director of plans, a post in which he worked with spymaster Thomas H. Karamessines. However, the publicity brought about by the Ramparts revealations did not help his career. Meyer role in Operation Mockingbird was further exposed in 1972 when he was accused of interfering with the publication of a book, The Politics of Heroin in Southeast Asia by Alfred W. McCoy. The book was highly critical of the CIA's dealings with the drug traffic in Southeast Asia. The publisher, who leaked the story, had been a former colleague of Meyer's when he was a liberal activist after the war. (61)

Cord Meyer - Deep Throat?

During the Watergate Scandal President Richard Nixon became concerned about the activities of the Central Intelligence Agency. Three of those involved in the burglary, E. Howard Hunt, Eugenio Martinez and James W. McCord had close links with the CIA. Nixon and his aides attempted to force the CIA director, Richard Helms, and his deputy, Vernon Walters, to pay hush-money to Hunt, who was attempting to blackmail the government. Although it seemed Walters was willing to do this, Helms refused. In February, 1973, Nixon sacked Helms. His deputy, Thomas H. Karamessines, resigned in protest.

It has been claimed that Cord Meyer was so upset by these developments that he was Deep Throat, the person who was leaking information to Bob Woodward of the Washington Post. The case for Meyer as Deep Throat has been put by Mark Riebling, the author of Wedge: From Pearl Harbor to 9/11 (2002): "Meyer had extremely intimate connections with Ben Bradlee, Woodward's boss at the Washington Post. Indeed, they were in-laws, having both married sisters from the socially prominent Pinchot family. Meyer's interface with Bradlee could have had a close professional aspect as well, since Meyer's main duty at CIA was to penetrate and influence leftist but anti-communist organs of opinion." (62)

James Schlesinger now became the new director of the CIA. Schlesinger was heard to say: “The clandestine service was Helms’s Praetorian Guard. It had too much influence in the Agency and was too powerful within the government. I am going to cut it down to size.” This he did and over the next three months over 7 per cent of CIA officers lost their jobs. (63) On 9th May, 1973, Schlesinger issued a directive to all CIA employees: “I have ordered all senior operating officials of this Agency to report to me immediately on any activities now going on, or might have gone on in the past, which might be considered to be outside the legislative charter of this Agency. I hereby direct every person presently employed by CIA to report to me on any such activities of which he has knowledge. I invite all ex-employees to do the same. Anyone who has such information should call my secretary and say that he wishes to talk to me about “activities outside the CIA’s charter”. (64)

There were several employees who had been trying to complain about the illegal CIA activities for some time. As Cord Meyer pointed out, this directive “was a hunting license for the resentful subordinate to dig back into the records of the past in order to come up with evidence that might destroy the career of a superior whom he long hated.” Schlesinger made his intentions clear: "I did quickly discover that he carried with him into his new job a firm conviction that the clandestine service which I temporarily headed exercised too dominant a role within the Agency, was out of phase with the intelligence requirements of the modern age, and was heavily overstaffed with aging veterans of past cold wars." (65) Meyer also suffered during this period and Schlesinger moved him to London where he became CIA chief of station in England.

According to Frances Stonor Saunders: "Increasingly mulish and unreasonable, Meyer had become a relentless, implacable advocate for his own ideas, which seemed to gravitate around a paranoiac distrust of everyone who didn't agree with him. His tone was at best argumentative, at worst histrionic and even bellicose." (66) Thomas Braden believed that Meyer had come under the influence of James Jesus Angleton. "Cord entered the Agency as a fresh idealist and left a wizened tool of Angleton... Whatever Angleton thought, Cord thought... Angleton was master of the black arts. He bugged everything in town, including me." (67) Arthur Schlesinger later recalled: "He (Cord Meyer) became so rigid, so unbending. I remember once he called me and suggested we meet for a drink. So I invited him over, and we sat upstairs in my house and talked. Years later, I asked the CIA for my file, and the last document in the file was a report on me by Cord Meyer! In my own house, over a drink, and he wrote a report on me. I couldn't believe it." (68)

Retirement

After leaving the CIA in 1977 Meyer became a a nationally syndicated columnist. He also wrote several books including an autobiography, Facing Reality: From World Federalism to the CIA. In the book Meyer commented on the murder of his wife: "I was satisfied by the conclusions of the police investigation that Mary had been the victim of a sexually motivated assault by a single individual and that she had been killed in her struggle to escape." (69) Carol Delaney, the longtime personal assistant to Meyer, later admitted: "Mr. Meyer didn't for a minute think that Ray Crump had murdered his wife or that it had been an attempted rape. But, being an Agency man, he couldn't very well accuse the CIA of the crime, although the murder had all the markings of an in-house rubout." (70)

The writer, C. David Heymann, began writing a book that was eventually published as Georgetown Ladies' Social Club (2004). The book concerned the group of women that had been part of this group that existed in the 1950s and 1960s. This included Mary Pinchot Meyer. Heymann became interested in her death and in February, 2001, he requested an interview with Cord Meyer, who at the time, was himself dying of lymphoma. Heymann asked Meyer if he still believed his wife had been "the victim of a sexually motivated assault". Meyer replied: "My father died of a heart attack the same year Mary was killed, " he whispered. "It was a bad time." And what could he say about Mary Meyer? Who had committed such a heinous crime? "The same sons of bitches," he hissed, "that killed John F. Kennedy." (71)

Cord Meyer died on 13th March, 2001. Nearly three years later in January 2004, E. Howard Hunt gave a taped interview with his son, Saint John Hunt, claiming that Lyndon Baines Johnson was the instigator of the assassination of John F. Kennedy, and that it was organised by Cord Meyer, David Atlee Phillips, Frank Sturgis and David Sanchez Morales. (72)

Primary Sources

(1) Cord Meyer, Facing Reality: From World Federalism to the CIA (1983)

For the members of my generation who spent our childhood and adolescence in the America of the 1930s, the Second World War did not come as an unexpected and unforeseen catastrophe, like an earthquake or tidal wave. Rather, the clouds that announced the approaching storm built up gradually on the horizon and cast shadows back across the landscape of our youth to trouble us from time to time with vague premonitions of impending disaster. For myself, I can remember the first time that the possibility of another world war entered my conscious mind. My twin brother and I were with our parents in a New York apartment in 1936 when we heard a newsboy shouting "Extra, Extra," in the street below. I was sent to buy a copy and can recall the black headlines proclaiming Hitler's invasion of the Rhineland. I listened as my father and mother discussed the bad news and agreed between themselves that war would eventually be unavoidable if the French and British did not act promptly to compel Hitler to withdraw his troops. My father had served in the First World War as a fighter pilot on the Western Front and my mother as a nurse in army hospitals in France, and, after they married, he had served in the diplomatic service abroad for a few years. As a result, I thought they knew what they were talking about turned up, and the hysterical foreign voice rose in a crescendo. "Hitler?" I ventured. He nodded. "What does it mean?" I asked. After a long pause, he answered slowly, as if he hated to have to say it, "I'm afraid it means war." We sat in silence for a few minutes, contemplating that idea from our different perspectives. Finally, I made my way to the beach, and the sand burned my bare feet. Looking at the gulls wheeling over the glittering sea, I thought to myself that I had better make the most of such days because they were not going to last.

By the time I entered Yale from St. Paul's School in the fall of 1939, war had been declared in Europe, and the march of German armies across that continent reverberated like approaching thunder. To an extraordinary extent, the university preserved its academic calm and usual ways. To me and to many of my classmates, the wide learning and intellectual brilliance of most of our professors was a revelation after the more limited teaching ability we had experienced in our high schools. I felt as if the doors had been thrown open and I had been ushered into a vast and splendid chamber where delicacies had been laid out in such profusion that one hardly knew where to begin.

(2) Cord Meyer, Facing Reality: From World Federalism to the CIA (1983)

During my sophomore year in 1940, the debate on campus began in earnest between those who argued for immediate American intervention on the side of beleaguered England and those who favored strict neutrality. In the columns of the Yale Daily News and in the - debates of the Political Union, the idealistic wing of the America First movement urged that we stay out of the ancient quarrels of the corrupt continent and concentrate instead on building a just society in our own land that could serve as a model and example to the world. The anti-war writing of the thirties and the history we had been taught of the bloody and inconclusive folly of the First World War led many to support this isolationist position. The interventionists stressed the horrors of the Nazi dictatorship and warned that, if we did not come to England's aid, we would be left alone to face Hitler's conquering armies. There were some who felt so strongly that England must be helped in its extremity that they quietly excused themselves from these collegiate debates and volunteered for service with the British and Canadian forces. The university was about as evenly divided on the issue as the country as a whole, where the closeness of the division was indicated by the fact that Congress extended the draft by the margin of a single vote.

I took no public part in this mounting controversy, having decided by that time that we had no choice but to fight if Hitler was to be stopped. I was sure that events would eventually force us into the war and was determined to use the remaining time to complete as much of my education as possible. However, in our dormitory rooms, private arguments flared long into the night between old friends. One of my friends, Arthur Howe, was a Christian pacifist and believed there was nothing that could justify killing another human being. I maintained with Plato that a citizen could not accept the protection of the laws and the education provided by the state and then refuse to obey those laws when they required him to bear arms in the state's justifiable defense. We did not convince each other, but Howe proved the strength of his convictions by departing to join the American Field Service, in which he drove ambulances for the British in the fighting in North Africa.

(3) Cord Meyer, Facing Reality: From World Federalism to the CIA (1983)

Only three days later the battalion was again thrown into the assault, this time against Parry Island at the southern end of the atoll. The fighting here was more intense, since the Japanese seemed more numerous and better prepared, but within forty-eight hours the battle was over. In the two landings, I had lost five of the forty-four men In my platoon and a disproportionately high number among the rifle platoon leaders had been killed or wounded, as was always the case since it was their job to lead each attack.

We were astonished by the behavior of the Japanese, although we had been amply warned. The sensible thing for the Japanese on Eniwetok to have done would have been to run up a flag of surrender when they first saw our armada of battleships, cruisers, and heavily loaded troopships steam into the lagoon. Among most Western armies, it would have been no disgrace to surrender to such an overwhr.ltning show of force. However, they chose to fight to the last man and to take as many of us with them as they could before they died. With their last bullet, they would commit suicide rather than allow themselves to be captured. If they were wounded they would hide a grenade so that those of us who attempted to help would be blown up with them. Only those most seriously wounded or those stunned into unconsciousness by a shell burst could be taken prisoner. We had a grudging respect for their suicidal bravery.

On their bodies and in their shelter trenches, we found letters that, when translated, shed some light on their determination to die fighting. Devoted to their emperor, they believed that to die in battle in his service was their highest duty. To allow oneself to be taken prisoner was to condemn oneself to permanent exile from the close-knit national family and to bring shame and dishonor on one's self and one's relatives. To these compelling motives, there was added the pervasive influence of official propaganda, which, we discovered, wildly misled these isolated garrisons as to the actual course of events and the progress of the war. One Japanese sergeant of the Imperial Marines, who had been captured while unconscious, announced defiantly on being brought aboard our ship that we might succeed in capturing Eniwetok but we would never win back California and Montana. It was hard to convince him that the Japanese army had not succeeded in conquering and occupying our entire West Coast.

(4) Cord Meyer, Waves of Darkness, Atlantic Monthly (January, 1946)

Abruptly, a heavy object bounced in the hole and rested against his right leg. It lay there and gave off a soft hissing sound. Though he moved with all the speed in his body, he felt in a dreamlike trance and seemed to stretch out his hand as a sleepwalker toward the object. His fingers closed around the corrugated iron surface of a grenade, and he knew that it was his own death that he held in his hand. His conscious mind seemed to be watching his body from a great distance as with tantalizing slowness his arm raised and threw the grenade into the dark. In mid-flight it exploded and the fragments whispered overhead. Another bounced on the edge of the hole and rolled in. He reached for it tentatively, as a child reaches out to touch an unfamiliar object.

A great club smashed him in the face. A light grew in his brain to agonizing brightness and then exploded in a roar of sound that was itself like a physical blow. He fell backward and an iron door clashed shut against his eyes.

He cried aloud once, as if through the sound the pain that filled him might find an outlet to overflow and diminish. Once more a long, rising moan was drawn from him and he lifted his hands in a futile gesture as though to rip away the mask of agony that clung to his face. Then, even in that extremity, the will to survive asserted itself. Through the fire that seemed to consume him, the knowledge that the enemy must be near-by made him stifle the scream that rose in his throat. If he kept quiet they might leave him for dead, and that was his only hope.

There was no time yet to wonder how badly he had been hurt. Like a poor swimmer, he struggled through the successive waves of pain that crashed over him. There would be a respite and then, again, he would be engulfed, until the dim light of consciousness almost went out. He pressed his hands to his temples, as if to hold his disintegrating being together by mere physical effort. His breath came chokingly. He allowed his head to fall to one side and felt the warm blood stream down his neck. There were fragments of teeth in his mouth and he let the blood wash them away.

It did not seem possible that anyone could have done this to him without reason. In a world on the edge of consciousness, he forgot the war and kept thinking that there must be some personal, individual explanation for what had happened. Over and over he repeated to himself, "Why have they done this to me? Why have they done this to me? What have I done? What have I done?" Like an innocent man convicted of some crime, he went on incoherently protesting his innocence, as if hoping that heaven itself might intervene to right so deep a wrong.At last he became calmer. Hesitantly, he set out to assess the damage done his body. The pain was worst in his face, but to investigate it was more than he yet dared. His right arm moved with difficulty, and blood slipped down his shoulder. It seemed that his ears were stuffed with cotton or that he stood at the end of a long corridor to which the sounds of the outside world barely penetrated.

From a great distance he heard a heavy thud on the ground, as of a fist pounded into the earth. There was another even heavier, followed by silence. He attempted to form the name of his friend with his lips. "George," he tried to whisper, but no sound came. He could see nothing, but in the loneliness of his pain reached out his hand. It seemed that a gradually widening expanse of darkness separated him from everything in the world, but that if he could only make contact with his friend it would be easy to find the way back. His fingers touched a dungaree jacket and felt the warm body beneath it. His hand moved upward, until suddenly he withdrew it. There was no need to search further.

A flood of the kindest memories obliterated niornentarily the knowledge of his own misfortune. 'I'hc empty body beside him had housed the bravest and the simplest heart. Between them there had been an unspoken trust and the complete confidence that comes only after many dangers shared together. If he had met him years later he would have had to say simply, "George." They would have shaken hands and the years between would have been nothing at all. Now, cold and impassable, stronger than time, stood death, and a hopeless, irremediable sense of loss flowed through him. The noise that at first had attracted his attention must have been the last despairing movement of his friend. Gently, he wiped the blood from his hand on his trouser leg. A long spasm of pain recalled him to his own condition.

Gratefully, he noticed that the edge of the pain was dulled. It continued to flow through his body, but his conscious self seemed to be slightly removed from it. The occasional rifle shots appeared to come from further and further away. His right arm had lost almost all power of movement. With care, he rested it across his stomach. While sufficient strength remained, he determined to know the extent of the damage done his face. Truth was never more terrible than at that moment when, fearfully, he raised his left hand to trace the contours of his personal disaster. As delicately as a blind man touches the features of one he loves, he ran his fingers over the lineaments of the face he did not know. Though there was considerable blood, the bones of his chin and nose seemed intact.

(5) Cord Meyer, journal (10th September 1944)

These are the first words I have written since that last evening on the ship before battle, since the evening of July twentieth. I wrote then in the expectation of death. I preferred to believe it almost inevitable and thereby thought to prepare myself for it. I had no wish for any foolish hopes that might lead me to avoid the duty then before me. My scale of values was simple. First and most to be preferred was life with honor. Secondly, death with honor. And what I hoped for least was life without honor. I find myself now with the first, and therefore in spite of the loss of an eye consider myself fortunate. If not my body, my integrity remains intact and I can truthfully say that as a soldier I have nothing to be ashamed of.

So then I have discharged my duty in that capacity, but the whole center and axis of my world has changed. I did not realize before how much I had completely discounted the future. If I thought of "after the war" at all, I thought of it as a man might think of a distant country which he was quite content to admit as beyond the possibility of his ever seeing. So if my life was not fruitful or pleasing, it was simple. I lived in the present and to a certain extent in the past and was assured in my own mind that there was no alternative to the life I led and the decision I had made. Now my duty is not so obvious, and the future full of conflicting alternatives. In the hospital convalescing as I am now, there is not yet the necessity for action. I inhabit temporarily a Lotus Eater's land of eating and sleeping but soon I must start again on that expanding adventure that is every man's life and before me are the most important decisions.

In many ways, I am not prepared to make that step. My future to a frightening extent is in my own hands, and there is no external circumstance and no man that can really sway my decision. To have so wide a choice is an enviable privilege I realize well enough, but it is also a large responsibility. The general notion of what I have to do is clear. I owe to those who fell beside me, and to those many others who will die before it's done, the assurance that I will do all that is in my small power to make the future for which they died an improvement upon the past. The question is how? In what field of endeavor? Where to begin? Education? Politics? Writing? Continue my education or not?

(6) Cord Meyer, Facing Reality: From World Federalism to the CIA (1983)

Looking back, I think that the impression Allen Dulles made on me was the decisive factor in my final decision to join the CIA. Behind his jovial and bluff exterior, he struck me as having a searching and undogmatic mind and a cosmopolitan and sophisticated knowledge of the world.... It seemed to me that an organization that had such a man in one of its top positions was one well worth working for. In the years that followed, I was to learn that in addition to his other qualities, he was a loyal and courageous friend in time of trouble.

(7) Deborah Davis, Katharine the Great (1979)

In 1952 Cord Meyer showed up as a CIA official in Washington knowing the names and activities of these same trade union and national liberation organizations, and the public story was that he had defected from the one-world movement because he had suddenly seen that world government was in danger of being Communistic. This transformation, so out of character for a man of his methodical intellect, caused people within the movement to believe that World Federalism may have been a lengthy intelligence assignment.

It is 1956, then, and Ben Bradlee's brother-in-law is stationed as a covert operations agent in Europe. He travels constantly, inciting "student" demonstrations, "spontaneous" riots and trade union strikes; creating splits among leftist factions; distributing Communist literature to provoke anti-Communist backlash. This localized psychological warfare is ultimately, of course, warfare against the Russians, who are presumed to be the source of every leftist political sentiment in Italy, France, the entire theater of Meyer's operations. In Eastern Europe his aim on the contrary is to foment rebellion. Nineteen fifty-six is the year the CIA learns that the Soviets will indeed kill sixty thousand agency-aroused Hungarians with armored tanks.

All of this goes on quite apart from his marriage. Mary does not have a security clearance, so he cannot tell her what he is doing most of the time. They begin to drift apart, and Mary draws closer to her sister and to Ben. When in the late fifties her marriage to Cord ends, she goes to live with Tony and Ben in Washington, where Newsweek has transferred him, and sets up her apartment and art studio in their converted garage...

It is only a matter of time, Angleton feels, until Bradlee makes a serious mistake, as he eventually does with the publication of Conversations with Kennedy, in which he mentions that Mary Meyer was murdered, but only in a footnote. A former Post editor named James Truitt is enraged at this; according to Truitt, Bradlee has forced him out of the paper in a particularly nasty fashion, with accusations of mental incompetence, and now Truitt decides to get back at Bradlee by revealing to other newspapers his belief that Bradlee's story on the Cord Meyers in Conversations with Kennedy was not the whole story; that Mary Meyer had been Kennedy's lover and that the day of her murder, James Angleton of the CIA searched her apartment and burned her diary. Their feud unnecessarily implicates Angleton, to his disgust and bitterness.

(8) Cord Meyer, Facing Reality: From World Federalism to the CIA (1983)

My participation in this struggle provided a unique opportunity to learn at first hand the strengths and weaknesses of Communist organizational strategy. As nothing else could, it gave me an understanding of how formidable is that dedicated man, the Communist true believer, and it taught me never to underestimate the potential strength of a disciplined Communist minority. It revealed the techniques of covert infiltration and control, through which Communists have too often captured organizations from those who awoke too late to these dangers. In microcosm, our struggle was an extension of the political battle being waged then in Western Europe between the democratic left and the mass Communist parties of Italy and France. My role in this small skirmish made me realize how much was at stake on the larger stage.

(9) Evan Thomas, The Very Best Men: The Early Years of the CIA (1995)

In late August 1953, just after Bissell had finished advising Frank Wisner and the CIA on how it might "roll back" communism in Eastern Europe, he had an experience that made him want to join the agency full-time. Taking a few weeks off from the Ford Foundation, he went cruising in Maine on his yawl, the Sea Witch, with Tom Braden and his wife, Joan. Braden was the head of the International Organizations Division at the CIA, in charge of running anti-Communist front groups in Western Europe.

The Sea Witch was anchored in a harbor in Penobscot Bay when Braden received an urgent message informing him that the McCarthyites had discovered a Red at the CIA. The man in question was Braden's deputy, Cord Meyer, a young war hero from St. Paul's and Yale, who had lost an eye in combat in the Pacific. The Bradens immediately abandoned their vacation and drove through the night back to Washington to stand by young Meyer. The FBI was unwilling to give him a security clearance, although typically refusing to say why. Dulles, Wisner, and other top agency officials refused to permit an FBI interrogation of Meyer. Eventually, they forced the FBI to reveal the charges against Meyer, which were flimsy at best (he had once appeared on the same speaking platform as a leftist professor and joined liberal groups deemed subversive by the Justice Department). In fact, Meyer was a staunch anti-Communist. After some procedural foot-dragging, he was cleared just before Thanksgiving and allowed to keep his job.

(10) Charles Ameringer, U.S. Intelligence Foreign Intelligence: The Secret Side of American History (1990)

Tom Braden later revealed that when he was head of the IOD, he had passed money to American labor leaders to fight Communist labor unions in Italy and Germany. Columnist Drew Pearson wrote, "Jay Lovestone, sometimes called (AFL-CIO president George) Meany's minister of foreign affairs... takes orders from Cord Meyer of the CIA." Lovestone, who was appointed executive secretary of the AFL Free Trade Union Committee after World War II and a dedicated cold warrior, needed little prodding from Braden and Meyer in opposing Communist influence in the international labor movement. At about the time that Meyer took charge of expanded operations in international organizations as chief of the Covert Action staff, Lovestone helped create the American Institute of Free Labor Development (AIFLD) for the purpose of training labor leaders in Latin America in labor organizing techniques and tactics. The AIFLD was one of several AFL-CIO entities that received covert funding from the CIA; Philip Agee alleged that its collaboration with CIA stations abroad was extremely close, amounting to a "country-team effort."

(11) Nina Burleigh, A Very Private Woman: The Life and Unsolved Murder of Presidential Mistress Mary Meyer (1998)

All of Washington was dying to be part of the new in crowd, and she was there. She was more inside than most men, including her exhusband, who would never find his name on a White House guest list even though he was at the very pinnacle of the intelligence community. When Kennedy was elected, Cord Meyer had hoped that his long wait in bureaucratic obscurity during the Eisenhower years would end with the advent of a Democratic administration. But that was not to be. The bad blood between him and Kennedy precluded that, as did the president's apparent fascination with his ex-wife.

First Cord tried for a diplomatic post. Jim Angleton asked Ben Bradlee to recommend Cord to Kennedy as ambassador to Guatemala. But Bradlee, who disliked Cord Meyer and for whom the feeling was returned (probably as a result of Bradlee's role in the European husband-dumping trip), never passed on the recommendation to Kennedy. Bradlee later wrote that he knew Kennedy did not like Cord and neither did he, owing to Cord Meyer's "derisive scorn for the people's right to know." In the book where he mentions his and Kennedy's dislike for Cord, he fails to mention the anecdote, widely discussed in Georgetown, about the night a drunken Cord Meyer lunged for Bradlee's neck across a dinner table.

As chief of the CIA's International Organizations Division, Cord Meyer sometimes met personally with Kennedy and his staff. Cord might have been involved in the anti-Castro plots, although his direct involvement was not revealed in public documents available as of 1997. He was certainly aware of them. In his private journal he described a 1960 meeting with a man named Pepe Figueres (probably Jose Figueres, president of Costa Rica, whose nickname was "Don Pepe") at which they "talked about what to do about Castro/Trujillo." He met often with Robert Kennedy after the Bay of Pigs. In October 1961 President Kennedy called Cord into the Oval Office to privately ask how to gain agency support for replacing CIA director Dulles with John McCone. Cord came away from that meeting feeling Kennedy was "much more serious and less arrogant than I'd known him before."

Cord was aware as early as October 1961 of Kennedy's interest in his ex-wife. Jim Angleton was paying keen attention to the young president's personal life and he had obliquely warned his old friend, although it doesn't appear he told Cord all he knew at the time. He later told Joan Bross, whose husband, John, was a high-ranking CIA official, that his bugging revealed that when Kennedy first called Mary, she went to the White House and found herself alone, and she asked to be taken home again. In his journal, Cord wrote that Angleton had told him Mary "baffles" Kennedy and that even with money and power, Kennedy "still yearns for a respect that eludes him from such as myself."

Cord eventually became troubled by the situation, although he never grasped the real nature of the relationship between his ex-wife and the President. In a long and melancholy journal entry in 1963 in which he listed his problems one by one, he wrote of "the peculiar relationship that exists between me and the President." Charles Bartlett, a mutual friend of Cord and the president, had spoken to Kennedy about a political appointment for Cord but "was told by JFK that due to some incident that occurred at the UN. conference in San Francisco in 1945 there was no possibility."

(12) Phil Agee, The National Student Association Scandal, Campus Watch (1991)

In February 1967, vice president Hubert Humphrey told a Stanford University audience that recent revelations of CIA activities represented "one of the saddest times, in reference to public policy, our Government has had." He was referring to the momentous exposures, then exploding across the front pages, of CIA meddling in the nation's largest student group, the United States National Student Association (NSA). The 1967 investigations, initially prompted by the editors of Ramparts magazine and authorized by various liberal-minded figures in corporate media and government, brought forth some of the most fully-disclosed operations regarding CIA influence over academia and a host of other domestic groups. Only after a presidential directive and promises by federal agencies to end covert support of domestic groups did the scandal subside. The damage control ultimately allayed such figures as Humphrey, Senator Robert Kennedy, and New York Times editorial page editor John Oakes. Yet subsequent failures to properly regulate covert actions along with legal loopholes and lack of clear policies within academic institutions have left persisting doubts regarding the use to which the CIA has put student groups and the academic community.

By most accounts, the relationship between the CIA and the NSA dates back to the early fifties, when both organizations were still in their infancies. As Tom Braden, who headed the agency's International Organization Division between '51 and '54, recounts in an article titled "I'm Glad the CIA is 'Immoral'," the NSA operation began after Allen Dulles, then in line for directorship, authorized Braden to provide support to domestic organizations in an all-out effort against the "international Communist front." Secret CIA funds were provided in 1952 to then NSA president William Dentzer, who later went on to become AID director in Peru. The New York Times also identified Cord Meyer, Jr. as having headed the NSA operation. However, the ties between the CIA and the National Student Association may actually stretch back to 1950, when, according to a New York Times interview with Frederic Delano Houghteling, then NSA secretary, the CIA gave him several thousand dollars to pay traveling expenses for a delegation of 12 representatives to a European international student conference.

(13) David Corn, Blond Ghost: The Shackley and the CIA's Crusades (1994)

It was poetic that on June 17- the day of the Watergate break-in Ted Shackley was in charge of the Western Hemisphere Division. Three of the five men who broke into the Democrats' office were Cuban exiles, past foot-soldiers in the covert war against Castro; another was an American veteran of the anti-Cuba campaign. They had been enlisted for the Watergate job by Hunt, who helped organize the Bay of Pigs invasion and now was part of the Nixon White House's undercover, dirty-tricks Plumbers unit. One of the five, Eugenio Rolando Martinez, was still on Shackley's payroll-another headache for Shackley and the Agency.

The day after the break-in, Shackley received a cable on Martinez from Jacob Esterline, his chief of station in Miami. The previous November, Martinez had mentioned his association with Hunt to the Miami station. But Martinez did not disclose the full extent of his contact-most notably, that he had participated with Hunt and the Plumbers in the breakin at the office of Daniel Ellsberg's psychiatrist. And in March of 1972, Martinez had told Esterline that Hunt was skulking about Florida for the White House and asked if the chief was aware of all the Agency activities in the Miami area. Clearly, Martinez thought Hunt was still with the Company - and that Esterline might be out of the loop. A worried Esterline wrote headquarters requesting information on Hunt's ties to the White House. The March 27, 1972, reply from Cord Meyer, the assistant deputy director for plans, was brusque: don't worry about Hunt in Miami; the ex-spy is on White House business. "Cool it," Meyer ordered.

In his dispatch to Shackley after the Watergate break-in, Esterline sought to preserve a cover story. The chief of station noted, accurately, that Martinez currently had two responsibilities for Shackley's division: reporting on maritime operations against Cuba and gathering intelligence on possible demonstrations at the Republican and Democratic conventions, both scheduled to be held in Miami. But Esterline deliberately kept out of his report information about Martinez's prior-and worrisome-references to Hunt's suspicious activities. Esterline did not reveal that the CIA had caught a whiff of the scandal to come and did nothing.

(14) Cord Meyer, journal entry (1st February, 1969)

The day before yesterday Dick Helms, Tom Karamessines and I met with Nixon, his new Secretary of State, Rogers, and Henry Kissinger, his aide for National Security Affairs, in the cabinet room of the White House. Nixon was very self-assured, quick to ask the relevant questions and put us at our ease in talking to him. The taut and withdrawn young man whom I first met at the junior Chamber of Commerce awards dinner in Chattanooga, Tenn., more than twenty years ago was replaced by a man who struck me as confidently in possession of the enormous power of that office. We shall see what successive crises do to him, but I suspect he will be a far better President than I or my liberal friends ever expected. We shall see.

(15) Lisa Todorovich, Washington Post (13th June, 1997)

Many Deep Throat theorists have guessed that Deep Throat was an FBI or White House official, but it is possible that a CIA official would have had access to the same information. In his 1994 book, "Wedge: The Secret War Between the FBI and the CIA," author Mark Riebling suggests two prime suspects from the agency's ranks.

Cord Meyer: Meyer joined the CIA in 1951 at the behest of Allen Dulles, director of central intelligence, after a stint as president of the U.N.-centric United World Federalists, a post which got him denounced by Moscow Radio as "the fig leaf of American imperialism" and accused of Communist activity by Wisconsin Sen. Joseph McCarthy. At the CIA, Meyer adopted a strident anti-Soviet stance and became a top aide to Richard Helms, director of central intelligence under presidents Johnson and Nixon. Helms was fired from his post in 1973 after he refused to help Nixon use the CIA to stall the FBI's Watergate probe.

According to Riebling, Meyer fits the Deep Throat profile that Bob Woodward has sketched: intellectual, combat veteran, heavy drinker and chain smoker. Like Woodward, Meyer attended Yale. He described his experiences in a 1983 book, "Facing Reality: From World Federalism to the CIA."