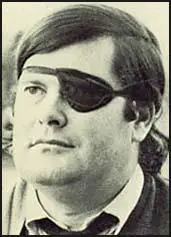

Warren Hinckle

Warren Hinckle was born in 1938. He worked as a journalist until being appointed editor of Ramparts Magazine in 1961. The magazine became the voice of the American New Left. It was also highly critical of the Warren Commission.

At the end of 1966 Desmond FitzGerald head of the Directorate for Plans, took charge of Operation Mockingbird. FitzGerald ordered Edgar Applewhite to organize a campaign against the magazine. Applewhite later told Evan Thomas for his book, The Very Best Men: "I had all sorts of dirty tricks to hurt their circulation and financing. The people running Ramparts were vulnerable to blackmail. We had awful things in mind, some of which we carried off."

In January 1967 Hinckle, met a man by the name of Michael Wood at the Algonquin Hotel in New York City. The meeting had been arranged by a public relations executive Marc Stone (the brother of I. F. Stone). Wood told Hinckle that the National Student Association (NSA) was receiving funding from the CIA. At first Hinkle thought he was being set-up. Why was the story not taken to the radical journalist, I.F. Stone?

However, after further research, Hinckle was convinced that the CIA had infiltrated the Non-Communist Left: "While the ADA-types and the Arthur Schlesinger model liberal kewpie dolls battled fascism by protecting their right flank with domestic Red-baiting and Cold War one-upmanship, the Ivy League delinquents who fled to the CIA – liberal lawyers, businessmen, academics, games-playing craftsmen – hatched a master plan of Germanic ambition that entailed nothing less than clandestine political control of the international operations of all important American professional and cultural organisations: journalists, educators, jurists, businessmen, et al. The standing CIA subsidy to the National Student Association was but one slice of a very complex pie." Hinckle even had doubts about publishing the story. Sol Stern, who was writing the article for Rapparts, "advanced the intriguing contention that such a disclosure would be damaging to the enlightened men of the liberal internationalistic wing of the CIA who were willing to provide clandestine money to domestic progressive causes."

Hinckle did go ahead with the story and took full-page advertisements in the Tuesday editions of the New York Times and Washington Post: "In its March issue, Ramparts magazine will document how the CIA has infiltrated and subverted the world of American student leaders, over the past fifteen years." For its exposé of the CIA, Ramparts received the George Polk Memorial Award for Excellence in Journalism and was praised for its "explosive revival of the great muckraking tradition."

After the closure of Ramparts Magazine, Hinckle was editor of the City of San Francisco, a radical weekly newspaper owned by Francis Ford Coppola, Scanlan's Monthly and Argonaut, a literary and political journal. He has also written for the San Francisco Independent and the San Francisco Chronicle. He also edited War News during the 1991 Gulf War.

Hinckle is also the author of several books including his autobiography, If You Have a Lemon, Make Lemonade (1974), The Richest Place on Earth (1978); The Fish is Red : the Story of the Secret War Against Castro (1981) and The George Bush Dilemma (1989). Hinckle was co-author with William Turner of Deadly Secrets: The CIA-Mafia War Against Castro and the Assassination of JFK (1992), a book about the CIA operations against Fidel Castro and the assassination of John F. Kennedy.

Primary Sources

(1) Warren Hinckle, If You Have a Lemon, Make Lemonade (1974)

Mark Lane was the New York lawyer and lecture artist who, before Garrison, was chief honcho among the Warren Commission critics. He was one of those people to whom I took an instant and irrational dislike. (Another is the dreadful Al Lowenstein, that boy scout of reform politicians.) I am hard put to explain why; demurring to the laws of slander, I can only cop out to brute instinct. Were I a dog, I would have growled when Lane came around. ("Watch out for the guys who come in fast," Cookie Picetti once told me, meaning that the type of guy who comes through the front door in a hurry, talking a busy streak as he breezes up to the bar, is invariably going to borrow money or cash a check that will go to the moon and bounce back.) Perhaps it was Lane's speed that turned me off. He moved about the world at a roadrunner's pace, a commercially-minded crusader, developing President Kennedy's murder into a solid multimedia property. Lane produced a book, Rush to Judgment, which sold like a Bible beachball at a Baptist resort; a movie of the same name, which consisted largely of on the street interviews with witnesses who said Oswald went this away, not that away; and a long-playing record on which, for the price of an LP, you could hear Lane's testimony to the Warren Commission - consisting, if my recollection is correct, of Lane telling the commission he knew something they didn't know, but couldn't tell them what it was.

(2) Warren Hinckle, If You Have a Lemon, Make Lemonade (1974)

My last communication with Garrison was on November 5, 1968. It was not untypical. I was interrupted in mid explanation to an unhappy investor (Eating's stormy departure had not helped the money-raising situation). The investor was turning a tinge yellow at my suggestion that the only way to insure the return of the $20,000 he had previously loaned Ramparts was to cover his bet with an additional $50,000. The interruption was an emergency long-distance telephone call from New Orleans. The caller was in no mood to inquire about the weather. "This is urgent," Jim Garrison said. "Can you take this in your mailroom? They'd never think to tap the mailroom extension."

I excused myself to go to the mailroom for a moment on a matter of high priority and left the investor, sputtering like a referee without a whistle, alone with the latest negative balance sheets. In the mailroom, two bearded Berkeleyite mail boys were running the postage machine under the influence of marijuana. I told them to take a walk around the block and get high on company time, and locked the door behind them.

Garrison began talking when I picked up the mailroom extension: "This is risky, but I have little choice. It is imperative that I get this information to you now. Important new evidence has surfaced. Those Texas oilmen do not appear to be involved in President Kennedy's murder in the way we first thought. It was the Military-Industrial Complex that put up the money for the assassination - but as far as we can tell, the conspiracy was limited to the aerospace wing. I've got the names of three companies and their employees who were involved in setting up the President's murder. Do you have a pencil?"

I wrote down the names of the three defense contractors - Garrison identified them as Lockheed, Boeing, and General Dynamics - and the names of those executives in their employ whom the District Attorney said had been instrumental in the murder of Jack Kennedy. I also logged a good deal of information about a mysterious minister who was supposed to have crossed the border into Mexico with Lee Harvey Oswald shortly before the assassination; the man wasn't a minister at all, Garrison said, but an executive with a major defense supplier, in clerical disguise. I knew little about ministers crossing the Rio Grande with Oswald - but after several years of fielding the dizzying details of the Kennedy assassination, I had learned to leave closed Pandora's boxes lie; I didn't ask.

I said that I had everything down, and Garrison said a hurried good-bye: "It's poor security procedure to use the phone, but the situation warrants the risk. Get this information to Bill Turner. He'll know what to do about the minister. I wanted you to have this, in case something happens... "

I unlocked the mailroom door, and returned to my office. The investor was gone.

I typed up a brief memorandum of the facts as Garrison had relayed them and burned my notes in an oversized ashtray I used for such purposes. I Xeroxed one copy of the memo, which I mailed to myself in care of a post office box in the name of Walter Snelling, a friendly, non-political bartender in the far-removed country town of Cotati, California, where I routinely sent copies of all supersecret Ramparts documents. That night I hand delivered the original to Bill Turner, the former FBI agent in charge of the magazine's investigation of the Warren Commission. Turner had drilled me in a little G-Man security lingo. According to our code, I called him at home and said something about a new vacuum cleaner. He replied that he'd be right over, and said he would meet me at the bar at Trader Vic's, which meant that I was to actually meet him at Blanco's, a dimly lit Filipino bar on the fringe of Chinatown, where we often held secret meetings. That was the way we did things in those days.

"Those days" encompassed several years of sniffing, as Sam Goldwyn might say, along the greenhorn trail of red herrings in the 26 volumes of the Report of the President's Commission on the Assassination of President Kennedy. We began asking rude questions in 1965, and by 1968, with paranoia in full bloom, we had divided almost everyone, by some sort of conspiracy litmus test, into "them" and "us." Even "us" was subdivided into good guys, not-so-good-guys, dangerous fanatics and fifth columnists. We ended up seeing "them" lurking behind every potted plant rented by the CIA; and, occasionally, we found a real spook in the shadows.

(3) Warren Hinckle, If You Have a Lemon, Make Lemonade (1974)

I met Garrison on a brisk, moon swept summer evening in 1967 at attorney Melvin Belli's penthouse pad, which sits atop a sagging building on Telegraph Hill like a diamond collar on a dented can. It was the New Orleans DA's first visit to San Francisco. Belli, who assumed the luckless defense of Jack Ruby after other lawyers had run away when Ruby began talking about cancer juice being injected in his veins, had invited the locals to hear Garrison's views on the assassination.

Belli doesn't sneeze without putting on a show, and the setting was adequate for staging Aida. The equivalent of several cable-car-loads of lawyers, police brass, newsmen and other San Francisco opinion-makers of smart chic and dowdy chic were munching rack of lamb and sucking in cocktails on Belli's vast bricked terrace hanging over the Bay, looking in through glass walls to the half-bookish, half-bare-Zenexhibitionist decor of the penthouse.

Garrison rose to the occasion. He was the essential frontier lawman-ectomorphic, taciturn, handsome, charming, dramatic in a properly low-keyed way. He spoke in the slightest of Southern drawls, just loud enough to be heard over the hoot of foghorns out in the Bay. He presented factually, without the hint of an opinion, a most incredible story of conspiracy, murder, and ineffectual conspiracy to cover the conspiracy-a story that was kerosene at the roots of the legitimacy of our system of government. Garrison rattled off dates, names, contradictory citations from the Warren Report, and extraordinary new evidence his New Orleans investigation had uncovered.

The DA was cool, sharp, informed, confident, convincing. He didn't leave a confirmed scoffer in the audience. A nervous lady in a low-cut print dress said something about how could high people in government be involved in such a thing. Garrison, who uses historical metaphors the way a tubercular does cough drops, replied: "Honorable men did in Caesar, Madam." His delivery brought a usually emotionless, grumpy Hearst reporter to his feet: "But, Mr. Garrison, if you're right, why it could destroy the government!" The DA replied with the calm of the frontier populist, Fess Parker explaining how to hitch a buckboard: "Well, sir, if telling the truth to the people of this country means that all the marble pillars of government in Washington will fall to the ground tonight; well, then, we'll just have to build ourselves a new government the next morning, maybe a little farther out West."

Garrison's official guide for the evening was an 18-year-old North Beach topless dancer with horn-rimmed glasses and well-buttressed breasts, assigned by his hosts to show him San Francisco's version of Bourbon Street. She looked at Jim doe like with unbridled admiration, a condition of enrapture shared, in varying degrees, by many among the rooftop assembly. The fresh converts to the cause of doubting Tomism waited to shake the DA's hand, standing around rubbing their goose bumps as the familiar early wet chill of a San Francisco summer fog closed in on the evening. Jim Garrison had put on one hell of a performance.

(4) Warren Hinckle & William Turner, Deadly Secrets: The CIA-Mafia War Against Castro and the Assassination of JFK (1992)

Mitch WerBell was a charter member of the intelligence Old Boy Network. He had been a secret agent with the OSS during World War II; thereafter he was always on the spot on the griddle where the Cold War was heating up. He was a player in the CIA's secret cross-border war against China in the 1950s through the 1960s; he went to Vietnam as a weapons adviser with the simulated rank of Brigadier General; and he did the prep work for the 1965 invasion of the Dominican Republic. He frequently worked with the CIA and infrequently worked against them. While the agency was fumbling the ball on its attempts to assassinate Fidel Castro, the ever gung-ho WerBell initiated his own assassination plots. His wild nocturnal speedboat rides to Cuba were scenes out of some paramilitary Strangelove movie-Mitch playing the pipes under a moonless Caribbean sky, the Confederate flag flapping from the rear of the boat. (Sometime later, the U.S. government hypocritically indicted WerBell for his anti-Castro plots while ignoring its own.)

The last decade of WerBell's life was filled with sufficient adventures and misadventures for the lifetimes of ten men. In 1973 WerBell began a "New Country Project" for a group of capitalist revolutionaries on Abaco Island in the Bahamas who wanted to shed the bondage of Nassau. The secessionists believed that the black population of the tourist islands was turning whites off and that sparsely settled Abaco, with a lower profile of blacks, could become a haven for investment money in gambling casinos, resorts, and housing restricted to the wealthy. The new currency would be called the rand, not in emulation of South Africa's medium of exchange but in honor of Ayn Rand, the dowager empress of rugged egoism.

WerBell sounded out his contacts in the high Arctic of the CIA and the State Department. He got the word that there would be no great American objection, provided there was no violence. WerBell was confident there would not be. He proceeded to sign up Soldier of Fortune-supreme Robert K. Brown to recruit a dozen Vietnam vets as the nucleus of an Abacoan standing army strong enough to dissuade Bahamian Premier Lyndon Pindling from invading with his own puny armed services. The date for secession was set for New Year's Day 1975.

However, three months before liberty day WerBell was indicted in Atlanta, and the plan had to be canceled. That indictment, later dropped, stemmed from his aggressive marketing of his silencer equipped Ingram machine gun, which starred in the movie Killer Force. (There are some interesting connections here. WerBell was manufacturing the Ingram under the name Defense Services, Inc., and marketing it through an outfit called Parabellum, which was headed by Anselmo Alliegro, Jr., an heir to the shadowy Ansan millions. Parabellum employed Gerry Hemming and Rolando Masferrer, nephew of the dreaded El Tigre Rolando Masferrer. When Anastasio Somoza's dictatorship in Nicaragua was collapsing in 1979, Cuban veterans of the Secret War rallied to his cause. Some engaged in combat against the insurgent Sandinista guerrillas; others acted as instructors with the elite National Guard, which had enabled the Somoza family to remain in power over the decades. One of the instructors was WerBell's partner in arms dealing, Anselmo Alliegro, Jr. In September 1980 Somoza, in exile in Paraguay, met a violent end. There were many flowers but few tears at his funeral.)

(5) Warren Hinckle, What Happened to the San Francisco Left? (29th December, 1998)

There was once in this fair and compassionate city an urgently topical publication called War News. Publication began on March 2, 1991 and ceased on March 16, 1991 with a circulation of 200,000. War News' purpose was to oppose the Gulf War, and, when the war ended, it ended.

The antiwar newspaper was an instant product of San Francisco's antiwar culture that made the city the epicenter of Vietnam War protests. It was largely a creation of the city's famous underground-comics artists of the '70s--Robert Crumb, S. Clay Wilson, Dan O'Neil, Gilbert Shelton, Winston Smith, and Ron Turner of Last Gasp Books, and writers included Hunter Thompson, Daniel Ellsberg, Andrew Kopkind, Ishamel Reed, Barbara Ehrenreich, and novelist John Berger. I was the editor of War News, which was financed by the Mitchell Brothers from their porn profits; it was a very San Francisco thing.

There were few Gulf War supporters in town - I seem to recall state senator Quentin Kopp and political consultant Jack Davis (when they were still speaking) waving little U.S. flags dork-like at a military parade--but most city politicos denounced the war and there were massive street protests; being against the invasion of Iraq in 1991 was as natural to San Francisco as summer fog.

Seven years later, in 1998, President Bill Clinton is trying to dodge the impeachment bullet and he drops more Tomahawk and Cruise missiles on Iraq than former president George Bush did during the entire Persian Gulf War and there is hardly a ripple of outrage on the city streets.

Whatever has happened to the Frisco left? Seven years ago, it would have had Clinton's head on a pike for carpet-bombing Iraq. And San Francisco would have been the starting gate for a push to impeach Clinton--not from the right for lying but from the left for the seriously high crime of using the war power, without authorization from Congress, to inflict civilian casualties to create a diversion from an obsessed special prosecutor's investigation of his sex life and his lies about it.

Over the weekend, I was on the phone with Gilbert Baker, trying to figure out what had gone wrong with the left in San Francisco. Baker is a political activist, the brilliant designer of the gay rainbow flag and the Nureyev of political demonstrations. He has caused more trouble on the streets of politics than cops have in their bad dreams.

"There was maybe a billion dollars' worth of bombs and ordinance in this diversion operation against Iraq--and Democrats are complaining that independent counsel Kenneth Starr's investigation cost $40 million," Baker said.

"In 1991, we marched in the streets by the thousands for days. We shut down the Bay Bridge over the Gulf War. Now a lot of people don't seem to care about civil rights, gay rights, you name it," he said.

Is there a left-wing passive freeze - like the lemon-crop frost - coming on? Are times so relatively good that yesterday's gladiators would rather curl up by the fire and ignore tomorrow's torments?

(6) Warren Hinckle, If You Have a Lemon, Make Lemonade (1974)

Sometime later, Jim Garrison took a long-distance call in his New Orleans office. The caller identified himself as the traveling representative of the Frontiers Publishing Company of Geneva. That firm had, the caller said, an important four volume original work on the Kennedy assassination which was about to be published in Europe. Would Mr. Garrison be interested in seeing the manuscript? Yeah, sure, send it, Garrison said, hanging up. Another nut.

The United States mails deposited a fat package in the New Orleans District Attorney's office. It contained three thick volumes of manuscript, each bound in black.

When this manuscript later emerged in book form, its title was Farewell America. The author, according to the book jacket, was James Hepburn, a thirty-four-year-old writer, former acquaintance of Jacqueline Bouvier, and former student at the London School of Economics and the Institute of Political Studies in Paris.

Garrison took one look, and called Ramparts to say that the Miracle of Fatima had occurred. Instead of a lovely lady, the creator had sent down something to read.

The next day a courier arrived from New Orleans lugging a Xerox of the sign from the KGB. It was a heavy sign: a thousand-odd pages of flawless typescript, as if part of an IBM demonstration at a convention of old-maid office managers, or from the Pope. Book manuscripts normally have at the minimum a few peanut butter and jelly stains on them, not to mention hen scratchings and other placental alterations. No author since the dawn of movable type has got himself together enough to dam the babbling brook of creativity, settle the last word and position the final comma, and then had the time or the money to completely and perfectly retype his manuscript before sending it to the publishers, or they to the printers. This masterpiece of the touch system was patently the product of some boiler-plate rewrite bank in the basement of an intelligence factory.

The content of the manuscript confirmed the validity of that superficial assessment of its origin. Garrison was amazed that the unheard-of Geneva publishing outfit had as well developed and documented a conspiracy theory as Garrison's own-with many of the same villains by name, and others of the same faces, but different aliases. The shock waves were equally as great at Ramparts. The mystery manuscript was as sprinkled with details as an ice cream cone dipped in chocolate jimmies. There were names and addresses, where relevant, about the clandestine operations of the Central Intelligence Agency. Much of the information was of the type that could only come from the CIA's own files or from the dossiers of a rival intelligence network. For instance, it was revealed that the CIA maintained a training center for saboteurs on Saipan Island in the Marianas, and that the Agency had exactly 28 agents in Iceland, working out of two offices, one at the American Embassy in Reykjavik, the other at the U.S. military base at Keflavik.

A Ramparts team of New Left researchers had been digging into the internal operations of the CIA for the better part of a year and had scavenged numerous scraps of available information, save whatever was tattooed on the inside of John McCone's belly button. A large part of the material in our files was unknown to the general press or public. But these manicured pages so inexplicably handed down from the mountain repeated, in a matter-of-fact manner, many of our zealously acquired CIA super secrets and revealed many more, all of which subsequently checked out. Whoever James Hepburn was, he had reliable sources of information about the inner workings of American intelligence.

The poop on the CIA was plotted in with the subtlety of a Vincent Price movie. The book's text gasped for breath as it crawled through hills and valleys created by mountainous footnotes, which were as jam-packed as a lifeboat with whole file drawers full of classified data. The manuscript revealed the locations of secret CIA schools for sabotage; exposed CIA-owned newspapers, radio stations and publishing houses in Cyprus, Beirut, Aden, Jordan, Kenya and other countries in Africa, the Middle East and the Far East; named the CIA's clandestine commercial "covers" in the United States, and recorded the Agency's role as co-director of the Eisenhower Administration, and examined its links-through Kermit Roosevelt in the fifties and John McCone in the sixties-to the oil industry. Among other epithets, the manuscript alleged that former "specialists" for the CIA's DCA (Department of Covert Activity) were members of an assassination "team" at Dallas.

Similar working details were disclosed about the KGB, the assessments being quite favorable. "In the domain of pure intelligence, the KGB is superior to the CIA." This supported our belief that the manuscript had been typed on Russian typewriters fitted with American characters.

Many sections of the book were non sequiturs which reminded me of Groucho Marx's line in Duck Soup: "A child of five would understand this. Send somebody to fetch a child of five." The gratuitous mention of a 1931 Paris detective story by an author who used the premonitory pseudonym "Oswald Dallas" made at least impish sense. But I couldn't figure the humor of numerous out-of-context references to Roy Cohn, the former boy witch hunter, whose selected quotations merited several vague footnotes with citations such as, "Roy Cohn, at the Stork Club in 1963."

Later, after we had gone scuba diving in the black waters of the manuscript's authorship, much of this strangeness was to be cleared up somewhat, as was the motivation behind a puzzling chapter alleging shocking Secret Service foul-ups which made the Dallas assassination almost a pushover. The critique amounted to a white paper on the deficiencies of the Secret Service, and was obviously prepared by someone very much on the Inside. There was a rather bitter attack on the competence of Kennedy White House aide Kenny O'Donnell, who supervised the security arrangements. The unsubstantiated attack made little sense as the mystery book went on to provide a lengthy analysis of the demonstrably superior security arrangements of other nations, particularly France and Russia, for protecting the lives of their chief executives. There was a puzzling hurrah for Daniel P. Moynihan, a professional thinker of moderate means, who so far as I knew had zero to do with guarding the President: "Only Daniel P. Moynihan, a former longshoreman, had some idea of such things."

The thesis of the mystery text was that of John F. Kennedy as the good guy-golden boy of American democracy, whose honest policies were so at odds with the power-mad and corrupt CIA and its billionaire oilmen kingmakers that he was accordingly snuffed. But by whom?

The three-volume manuscript was accompanied by a cryptic note: If we were interested in seeing the fourth volume, we should cable a law firm in Geneva, and arrangements would be made. An obvious deduction, Watson: The fourth volume would name the murderers.

We cabled. We waited. A week later Garrison telephoned: "You know that fourth volume? Well, it just walked in the door."

There was to be a further complication. The messenger who had arrived in New Orleans from Geneva did not have the final volume with him. We would have to send a representative to Geneva to inspect it in person.

At that, I began to wonder if this was a present from the KGB, or a booby trap from somebody else.

Garrison immediately dispatched an emissary to Geneva to collect the tainted goods. Selected for this delicate task was Steve Jaffe, the peach fuzz side of twenty-five, who had already established a reputation as a professional photographer and was envied by other assassination sleuths because he had credentials from Garrison authorizing him a special investigator for the District Attorney's office, and was so registered in Baton Rouge.

In Geneva, Jaffe discovered that the office of Frontiers Publishing was a desk in a large Swiss law firm that specialized in representing Swiss banks. The most concrete information the law firm would provide was that Frontiers was a Liechtenstein corporation. The real headquarters, Jaffe was told, were in Paris. Jaffe went to Paris.

The Paris editorial offices of the elusive Frontiers were in the modern offices of a famous international law firm. Nobody was minding the store but lawyers. It was explained to Jaffe that important "financial interests" were behind the publishing of the book. At one point, the smarmy suggestion was dropped that the Kennedy family itself had underwritten part of the costs.

Jaffe had been asked to interview the author, James Hepburn, and question him about his sources.

The answer came from Paris: It is impossible to meet the author. The author is a "composite."

As my friend Tupper Saussy, the composer, once wrote, "I turned on the Today show and wished it were yesterday." Additional communications across the Atlantic weaved back and forth like carrier pigeons drunk on elderberries. Such facts or suppositions of fact as emerged made only one thing clear to me: we were shadowboxing with a high-level intelligence operation-although no longer necessarily the KGB. French intelligence was suddenly in the running; even the ubiquitous CIA became suspect.

Farewell America was published in Germany, with fanfare but without the missing final volume, and became a moderate best seller. The phony book was syndicated in Bild, Germany's largest daily newspaper, which is owned by Axel Springer, who is not exactly a raving Bolshevik. Why would Springer authenticate such a KGB plant? The inevitable suspicion arose that this might be a triple-decker CIA cake with Ian Fleming icing to somehow entrap Ramparts.

Further investigation revealed that Frontiers Publishing Company of Vaduz, Liechtenstein, had never published a book before, and had no apparent plans to publish anything else in the future.

Farewell America was then published in France in a handsome edition by Frontiers. The review in L'Express was quoted on the book's jacket ". . . . the most violent indictment ever written by a man about his country, out of love for that country." Not a bad notice for a composite.

Jaffe reported that he had tracked down the publisher of Frontiers. He identified him as one Michel. According to the curriculum vitae supplied to Jaffe, Michel had been the publisher of a French women's magazine, in the early sixties. Before that, he had been a combat officer in the French army in Indochina, had studied at Harvard for a time, and had attended the French Diplomatic Training School. Jaffe said that Michel was the key to the preparation of the mystery book and added his opinion, which he said was not totally unconfirmed by Michel, that the "Publisher" was highly placed in French intelligence.

Whoever he was, the "Publisher" knew his way around the Elysee Palace.

When Jaffe asked him for some authentication of the material in the book, Michel whisked him into the Elysee Palace and into the private office of the Director of the French Secret Service, Andre Ducret.

Ducret was most gracious to the young American. He said that the Secret Service of France had indeed provided certain information for parts of Farewell America. He gave Jaffe photographs and diagrams hand-drawn on his personal stationery supplementing the criticisms of the American Secret Service made in the book. Ducret also told Jaffe that he had knowledge of the weapon that had actually been used in the Kennedy assassination-which was not the dime store rifle the Warren Commission said Oswald fired.

Jaffe asked the Secret Service head if there was any chance of getting a letter to General de Gaulle. Ducret said it was certainly possible, although he had no way of knowing if the General would have time to send an answer. Jaffe gave Ducret a letter stating the gist of his mission, and inquiring into whatever clarification was possible on the role of the French government in the publication of the book.

Ducret said he would personally take .Jaffe's letter to General de Gaulle. He returned about fifteen minutes later and handed Jaffe De Gaulle's engraved card, with a personal note scribbled on it: " GENERAL DE GAULLE, Je suis tres sensible a la, confiance que vous m'exprimez."

The head of the French Secret Service also told jaffe in so many words, just how important that he, too, thought both Jaffe's mission and Garrison's investigation were, and how France appreciated their efforts. Jaffe left the Elysee Palace, equally impressed and puzzled.

Michel indicated that the "documents" on which the book was based were locked up for safekeeping in a Liechtenstein bank vault. However, he said Jaffe was in luck as one of the sources, a French intelligence agent known as "Phillipe," was in town. Michel said that Phillipe had interviewed a member of the paramilitary sharp shooting team that had murdered Kennedy at Dealey Plaza. At midnight, Michel drove Jaffe to the Club Kama, a dingy Latin Quarter bar, to have a drink with the spook.

Phillipe spoke only in metaphor. Most of his metaphors were about the Hotel Luna in Mexico City, which he implied had-in the assassination year of 1963-a "Cuban band," whose musicians had dangerous "instruments."

Then Michel said there was just one little thing more before we got to see the fourth volume with the yellow pages listing Kennedy's murderers. Frontiers was anxious to publish Farewell America in America-and wanted Ramparts to publish it, just as Axel Springer had been so kind to have done in Germany.