Spartacus Blog

The History of Freedom of Speech

Wednesday, 13th January, 2014

There has been a lot of discussion about freedom of expression since the killing of the eight journalists at the offices of Charlie Hebdo, the French satirical weekly newspaper, that had published a number of controversial Muhammad cartoons. It has been suggested that there is a long tradition of freedom of speech in the UK and that we need to defend this ancient right in response to this terrorist outrage. Although journalists have been keen to point this out it seems their editors are unwilling to publish any of the offending cartoons. It has also emerged that official guidelines previously published online said that the Prophet revered by Muslims “must not be represented in any shape or form” in BBC output.

Freedom of expression is something that has taken a long time to establish in this country. Dominant religious, political and cultural institutions have always used their power to protect themselves from criticism. An interesting case in our history concerns Anne Askew who was burnt at the stake on 16th July 1546. Anne had taken on every powerful institution that existed in Tudor England.

Anne was the daughter of Sir William Askew (1489–1541) a large landowner and the former MP for Grimsby. When she was fifteen her family forced her to marry Thomas Kyme. Anne rebelled against her husband by refusing to adopt his surname. The couple also argued about religion. Anne was a supporter of Martin Luther, while her husband was a Roman Catholic. From her reading of the Bible she believed that she had the right to divorce her husband. For example, she quoted St Paul: "If a faithful woman have an unbelieving husband, which will not tarry with her she may leave him"?

In 1544 Askew decided to travel to London and request a divorce from Henry VIII. This was rejected and in March 1546 she was arrested on suspicion of heresy. She was questioned about a book she was carrying that had been written by John Frith, a Protestant priest who had been burnt for heresy in 1533, for claiming that neither purgatory nor transubstantiation could be proven by Holy Scriptures. She was interviewed by Edmund Bonner, the Bishop of London who had obtained the nickname of "Bloody Bonner" because of his ruthless persecution of heretics.

After a great deal of debate Anne Askew was persuaded to sign a confession which amounted to an only slightly qualified statement of orthodox belief. With the help of her friend, Edward Hall, the Under-Sheriff of London, she was released after twelve days in prison. She was sent back to her husband. However, when she arrived back to Lincolnshire she went to live with her brother, Sir Francis Askew.

In February 1546 conservatives in the Church of England, led by Stephen Gardiner, bishop of Winchester, began plotting to destroy the radical Protestants. He gained the support of Henry VIII. As Alison Weir has pointed out: "Henry himself had never approved of Lutheranism. In spite of all he had done to reform the church of England, he was still Catholic in his ways and determined for the present to keep England that way. Protestant heresies would not be tolerated, and he would make that very clear to his subjects." In May 1546 Henry gave permission for twenty-three people suspected of heresy to be arrested. This included Anne Askew.

Gardiner selected Askew because he believed she was associated with Henry's sixth wife, Catherine Parr. Catherine also criticised legislation that had been passed in May 1543 that had declared that the "lower sort" did not benefit from studying the Bible in English. The Act for the Advancement of the True Religion stated that "no women nor artificers, journeymen, serving men of the degree of yeomen or under husbandmen nor labourers" could in future read the Bible "privately or openly". Later, a clause was added that did allow any noble or gentlewoman to read the Bible, this activity must take place "to themselves alone and not to others". Catherine ignored this "by holding study among her ladies for the scriptures and listening to sermons of an evangelical nature".

Gardiner believed the Queen was deliberately undermining the stability of the state. Gardiner tried his charm on Askew, begging her to believe he was her friend, concerned only with her soul's health, she retorted that that was just the attitude adopted by Judas "when he unfriendly betrayed Christ". On 28th June she flatly rejected the existence of any priestly miracle in the Eucharist. "As for that ye call your God, it is a piece of bread. For a more proof thereof... let it but lie in the box three months and it will be mouldy."

Gardiner instructed Sir Anthony Kingston, the Constable of the Tower of London, to torture Askew in an attempt to force her to name Catherine Parr and other leading Protestants as heretics. Kingston complained about having to torture a woman (it was in fact illegal to torture a woman at the time) and the Lord Chancellor Thomas Wriothesley and his assistant, Richard Rich took over operating the rack. Despite suffering a long period on the rack, Askew refused to name those who shared her religious views. According to Askew: "Then they did put me on the rack, because I confessed no ladies or gentlemen, to be of my opinion... the Lord Chancellor and Master Rich took pains to rack me with their own hands, till I was nearly dead. I fainted... and then they recovered me again. After that I sat two long hours arguing with the Lord Chancellor, upon the bare floor... With many flattering words, he tried to persuade me to leave my opinion... I said that I would rather die than break my faith."

Askew was removed to a private house to recover and once more offered the opportunity to recant. When she refused she was taken to Newgate Prison to await her execution. On 16th July 1546, Agnew "still horribly crippled by her tortures" was carried to execution in Smithfield in a chair as she could not walk and every movement caused her severe pain. It was reported that she was taken to the stake which had a small seat attached to it, on which she sat astride. Chains were used to bind her body firmly to the stake at the ankles, knees, waist, chest and neck. Askew's executioner helped her die quickly by hanging a bag of gunpowder around her neck.

Bishop Stephen Gardiner had a meeting with Henry VIII after the execution of Anne Askew and raised concerns about his wife's religious beliefs. Henry, who was in great pain with his ulcerated leg and at first he was not interested in Gardiner's complaints. However, eventually Gardiner got Henry's agreement to arrest Catherine Parr and her three leading ladies-in-waiting, "Herbert, Lane and Tyrwhit" who had been involved in reading and discussing the Bible.

Henry then went to see Catherine to discuss the subject of religion. Probably, aware what was happening, she replied that "in this, and all other cases, to your Majesty's wisdom, as my only anchor, Supreme Head and Governor here in earth, next under God". He reminded her that in the past she had discussed these matters. "Catherine had an answer for that too. She had disputed with Henry in religion, she said, principally to divert his mind from the pain of his leg but also to profit from her husband's own excellent learning as displayed in his replies." Henry replied: "Is it even so, sweetheart? And tended your arguments to no worse end? Then perfect friends we are now again, as ever at any time heretofore." Gilbert Burnett has argued that Henry put up with Catherine's radical views on religion because of the good care she took of him as his nurse. The next day Chancellor Thomas Wriothesley arrived with a detachment of soldiers to arrest Catherine. Henry told him he had changed his mind and sent the men away.

During his reign Henry VIII (1509-1547) executed 81 heretics. The Protestant government of Edward VI (1547-1553) took a moderate approach to the subject and only two heretics were burnt at the stake. His sister, Mary (1553-1558) was a much more passionate hunter of heretics and an estimated 280 people were put to death during her five-year reign.

Elizabeth (1558-1603) had a fairly good record of only ordering two heretics to be burnt at the stake. However, she could be very cruel if anyone dared to express views that were critical of her. In 1579 Elizabeth's officials were involved in negotiations about the possible marriage to the Duke of Alençon. Lord Chancellor Christopher Hatton was against the match "but joined with the rest of the council in a sullen acquiescence, offering to support the match if it pleased her." However, there was a great deal of opposition to the proposed marriage. As Elizabeth Jenkins has pointed out: "The English dislike of foreign rule, which had shown itself strongly on the marriage of Mary Tudor, was now indissolubly connected with a fear of Catholic persecution. The idea of a French Catholic husband for the Queen roused the abhorrence which, in the Puritans, reached almost to frenzy."

John Stubbs was totally opposed to the marriage and wrote a pamphlet, The Discovery of a Gaping Gulf, criticizing the proposed marriage. It accused certain evil "flatters" and "politics" of espousing the interests of the French court "where Machiavelli is their new testament and atheism their religion". He described the proposed union as a "contrary coupling" and an "immoral union" like that of a cleanly ox with an uncleanly ass". Stubbs accused the Alençon family of suffering from sexually transmitted diseases and that Elizabeth should consult her doctors who would tell her she was exposing herself to a frightful death. Stubbs also argued that, at forty-six, Elizabeth may not have children or may be endangered in childbirth.

On 27th September 1579 a royal proclamation was issued prohibiting the circulation of the book. On 13th October Stubbs, Hugh Singleton (the printer), and William Page (who had been involved in the distribution of the pamphlet) were arrested. Elizabeth wanted to be immediately executed by royal prerogative but eventually agreed to their trial for felony. The jury refused to convict, and they were then charged with conspiring to excite sedition. The use of this statute was criticized by Judge Robert Monson. He was imprisoned and removed from the bench when he refused to retract.

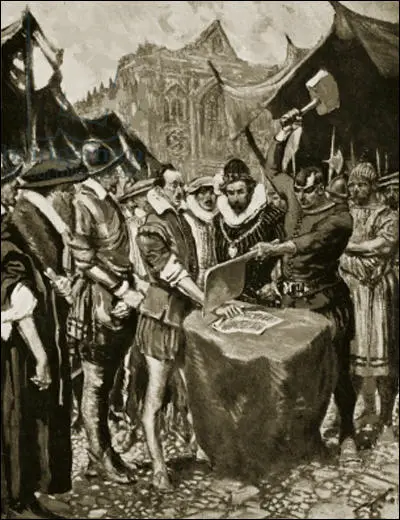

Stubbs, Singleton and Page were all found guilty of sedition and were sentenced to have their right hands cut off and to be imprisoned, though it appears that Singleton was pardoned because of his age: he was about eighty. The sentence was carried out at the market place in Westminster on 3rd November 1579, with surgeons present to prevent them bleeding to death. Stubbs made a speech on the scaffold where he asserted his loyalty and asked the crowd to pray that God would give him strength to endure the punishment.

William Camden points out in The History of Queen Elizabeth (1617): "Stubbs and Page had their right hands cut off with a cleaver, driven through the wrist by the force of a mallet, upon a scaffold in the market-place at Westminster... I remember that Stubbs, after his right hand was cut off, took off his hat with his left, and said with a loud voice, 'God Save the Queen'; the crowd standing about was deeply silent: either out of horror at this new punishment; or else out of sadness."

An eyewitness claims it took three blows before his hand was chopped off. The bleeding was stopped by searing the stump with a hot iron. Stubbs fainted but William Page walked off unaided, and found the strength to shout: "I have left there a true Englishman's hand!" Stubbs and Page were then taken back to the Tower of London. Parliament was due to meet in October, 1579, to discuss her proposed marriage. Elizabeth did not allow this to happen. Instead she called a meeting of her council. After several days of debate the council remained deeply divided, with seven of them against the marriage and five for it. "Elizabeth burst into tears. She had wanted them to arrive at a definite decision in favour of the marriage, but now she was once more lost in uncertainty."

Elizabeth was shocked to discover that the punishment of Stubbs had a negative impact on her popularity. As Anka Muhlstein pointed out: "Thanks to her unerring political instinct, Elizabeth realized at once that she had taken the wrong tack. Her people's respect and affection, which she had never lacked hitherto, were essential to her. The easy-going relationship she enjoyed with her subjects warmed her heart." In January, 1580, Queen Elizabeth admitted to Alençon that public opinion made their marriage impossible.

On 11th April 1612, Edward Wightman became the last heretic to be burnt at the stake when he was put to death in Lichfield. However, people were still in danger of serving long-terms of imprisonment if they made comments that were considered dangerous by religious and political leaders. There was also a strict form of censorship that attempted to stop people from questioning the status quo.

An interesting case concerns the political career of Tom Paine. In 1791 Paine published his most influential work, The Rights of Man. In the book Paine attacked hereditary government and argued for equal political rights. Paine suggested that all men over twenty-one in Britain should be given the vote and this would result in a House of Commons willing to pass laws favourable to the majority. The book also recommended progressive taxation, family allowances, old age pensions, maternity grants and the abolition of the House of Lords.

The British government was outraged by Paine's book and it was immediately banned. Paine was charged with seditious libel but he escaped to France before he could be arrested. Paine announced that he did not wish to make a profit from The Rights of Man and anyone had the right to reprint his book. It was printed in cheap editions so that it could achieve a working class readership. Although the book was banned, during the next two years over 200,000 people in Britain managed to buy a copy.

To escape imprisonment Paine fled to Paris and in 1792 he became a French citizen and was elected to the National Convention. The following year he discovered that even revolutionary governments were not in favour of freedom of speech and when he opposed the execution of Louis XVI he was arrested and kept in prison under the threat of execution from 28th December 1793 and 4th November 1794.

Paine's book did help to stir up debate on the idea of freedom of speech. Thomas Spence, a schoolmaster from Newcastle, moved to London and attempted to make a living my selling Paine's Rights of Man on street corners. He was arrested but soon after he was released from prison he opened a shop in Chancery Lane where he sold radical books and pamphlets. In 1793 he started a periodical, Pigs' Meat. He said in the first edition: "Awake! Arise! Arm yourselves with truth, justice, reason. Lay siege to corruption. Claim as your inalienable right, universal suffrage and annual parliaments. And whenever you have the gratification to choose a representative, let him be from among the lower orders of men, and he will know how to sympathize with you."

In May 1794 Spence was arrested and imprisoned and because Habeas Corpus had been suspended, the authorities were able to hold him without trial until December 1794. He was eventually released but it was not long before he was back behind bars for selling what the government described as "seditious publications".

One way the government attempted to silence radical newspapers was by taxation. These taxes were first imposed on British newspapers in 1712. The tax was gradually increased until in 1815 it had reached 4d. a copy. As few people could afford to pay 6d. or 7d. for a newspaper, the tax restricted the circulation of most of these journals to people with fairly high incomes.

Richard Carlile was another one who tried to make a living from selling the writings of Tom Paine on street corners. In 1817 Carlile decided to rent a shop in Fleet Street and become a publisher. This included the radical newspaper called The Republican. On 16th August 1819, Carlile was one on the main speakers at a meeting on parliamentary reform at St. Peter's Fields in Manchester. The local magistrates ordered the yeomanry (part-time cavalry) to break up the meeting. Just as Hunt was about to speak, the yeomanry charged the crowd and in the process killed eleven people. Afterwards, this event became known as the Peterloo Massacre.

In the next edition of his newspaper he wrote a first-hand account of the massacre. Carlile not only described how the military had charged the crowd but also criticised the government for its role in the incident. Under the seditious libel laws, it was offence to publish material that might encourage people to hate the government. In October 1819, Carlile was found guilty of blasphemy and seditious libel and was sentenced to three years in Dorchester Gaol. Carlile was also fined £1,500 and when he refused to pay, his Fleet Street offices were raided and his stock was confiscated.

When Richard Carlile was released from prison in November 1825 he returned to publishing newspapers. Carlile was now a strong supporter of women's rights. He argued that "equality between the sexes" should be the objective of all reformers. Carlile wrote articles in his newspapers suggesting that women should have the right to vote and be elected to Parliament. In 1826 he also published Every Woman's Book, a book that advocated birth control and the sexual emancipation of women.

In 1831 Henry Hetherington began publishing The Poor Man's Guardian. Hetherington's refused to pay the 4d. stamp duty on each paper sold. On the front page, where the red spot of the stamp duty should have been, Hetherington printed the slogan "Knowledge is Power". Underneath were the words, "Published in Defiance of the Law, to try the Power of Right against Might".

By 1833 circulation had reached 22,000, with two-thirds of the copies being sold in the provinces. In a three year period, twenty-five of these forty agents went to prison for selling an unstamped newspaper. One of those was arrested was George Julian Harney, who was imprisoned three times for selling the Poor Man's Guardian. Later Harney was to become the editor of the very successful Chartist newspaper, The Northern Star.

The campaign for an untaxed press obtained a boost in June 1834 when it was ruled that the Poor Man's Guardian was not an illegal publication. The newspaper reported: "After all the badgerings of the last three years - after all the fines and incarcerations - after all the spying and blood-money, the Poor Man's Guardian was pronounced, on Tuesday by the Court of Exchequer (and by a Special Jury too) to be a perfectly legal publication." As a result of this court ruling, Henry Hetherington invested in a new printing press, the Napier double-cylinder, a machine capable of printing 2,500 copies an hour.

The authorities responded by ordering an increase in the prosecution of newspaper sellers. Joseph Swann was another reformer who tried to make a living from selling the The Poor Man's Guardian. In 1835 he was sentenced to four and a half years for selling the newspaper. During the trial he explained his actions. "I have been unemployed for some time, neither can I obtain work, my family are starving. And for another reason, the most important of all, I sell them for the good of my countrymen."

In 1835 the two leading unstamped radical newspapers, The Poor Man's Guardian, and The Police Gazette, were selling more copies in a day than The Times sold all week. It was estimated at the time that the circulation of leading six unstamped newspapers had now reached 200,000.

The government decided to bring an end to the reformist press. Ignoring the court decision, in 1835 the offices of the newspaper were raided. Hetherington's stock and equipment, including his new Napier printing machine, was seized and destroyed. For a while Henry Hetherington printed the Poor Man's Guardian on borrowed equipment but in December, 1835, he was forced to cease publication.

Although the authorities had stopped burning heretics people did not have complete freedom of speech in religious matters. In August 1842, George Holyoake, the editor of Oracle of Reason, was charged with "condemning Christianity" in a speech he made at Cheltenham. He was found guilty and sentenced to six months in prison. This did not stop Holyoake in his campaign for freedom of speech and established The Reasoner. Over the next fifteen years the journal became one of the most important working class journals of the 19th century.

Despite the extension of the vote, the Church was still able to prevent the publication of books and pamphlets. For example, the Church was totally opposed to the use of contraception to control family size. In 1877 Annie Besant and Charles Bradlaugh decided to publish The Fruits of Philosophy, written by Charles Knowlton, a book that advocated birth control. Besant and Bradlaugh were charged with publishing material that was "likely to deprave or corrupt those whose minds are open to immoral influences". In court they argued that "we think it more moral to prevent conception of children than, after they are born, to murder them by want of food, air and clothing." Besant and Bradlaugh were both found guilty of publishing an "obscene libel" and sentenced to six months in prison. At the Court of Appeal the sentence was quashed.

Even in the 20th century the Church continued to use its influence to try to stop people discussing this issue. Guy Aldred was someone who spent his life campaigning against censorship. In 1909 he was sentenced to twelve months hard labour for printing the August issue of The Indian Sociologist, an Indian nationalist newspaper edited by Shyamji Krishnavarma.

In 1921 Aldred established the Anti-Parliamentary Communist Federation (APCF), a breakaway group from the Communist Party of Great Britain. He edited the organisation's newspaper, The Communist. The authorities began to investigate this group and Aldred, Jenny Patrick, Douglas McLeish and Andrew Fleming were eventually arrested and charged with sedition. After being held in custody for nearly four months they appeared at Glasgow High Court on 21st June 1921. They were all found guilty. The Socialist reported: "Lord Skerrington then passed sentences: Guy Aldred, one year: Douglas McLeish three months: Jane Patrick, three months, Andrew Fleming (the printer), three months and a fine of £50, or another three months."

Patrick Dollan, wrote in The Daily Herald: "Guy Aldred, in prison for exercising the traditional right of free speech, was imprisoned four months before his trial, then sentenced for a year and not allowed to count the four months he had already served as part of this imprisonment. The brutality of this sentence is a disgrace to the country, and nothing can remove that disgrace except the organised power of Labour."

After his release from prison Guy Aldred and his partner, Rose Witcop, joined the campaign for birth-control information that had began by Marie Stopes publishing a concise guide to contraception called Wise Parenthood. Aldred and Witcop published several pamphlets on birth-control and on 22nd December, 1922 he was prosecuted for publishing Family Limitation, a pamphlet written by Margaret Sanger. Aldred conducted his own defence. Among the witnesses he called was Sir Arbuthnot Lane, a leading surgeon at Guy's Hospital. He argued that the pamphlet should be read by every young person about to be married. Despite this, the magistrate ordered the books to be destroyed "in the interests of the morals of society."

As one can see, the freedom to express opinions that are not shared by people in authority, has been a long-drawn struggle. For most of the time, those in authority, use the most extreme form of punishment they can get away with. Henry VIII and Mary believed in setting fire to people. Elizabeth, who considered herself a humane ruler, preferred the idea of removing the offender's right hand. However, as she discovered, extreme forms of punishment can lose you the support of your people. In January, 1580, Elizabeth admitted to the Duke of Alençon that public opinion made their marriage impossible.

In the 20th century dictators such as Adolf Hitler and Joseph Stalin had few qualms about executing those who advocated free speech. (Stalin discovered the best way of keeping people quiet is to threaten the lives of their children. Something that has been repeated recently by people using social media.) Freedom of speech is denied in all dictatorships.

Over the last few years, people who have been unable to gain the right to freely express their views in their own society, have decided to use methods employed by religious and political dictatorships, to silence people living in democracies. In many ways it has worked because people have employed self-censorship. As Miloš Forman, who worked as a film director in the communist regime of Czechoslovakia, once pointed out: "The worst evil is - and that's the product of censorship - is the self-censorship, because that twists spines, that destroys my character because I have to think something else and say something else, I have to always control myself."

The journalists at Charlie Hebdo were unwilling to impose self-censorship and they have paid the ultimate price. Their lives will not have been wasted if newspaper and television companies follow the example of Wikipedia and refuse to be intimidated into silence.

Previous Posts

The History of Freedom of Speech (13th January, 2015)

The Christmas Truce Football Game in 1914 (24th December, 2014)

The Anglocentric and Sexist misrepresentation of historical facts in The Imitation Game (2nd December, 2014)

The Secret Files of James Jesus Angleton (12th November, 2014)

Ben Bradlee and the Death of Mary Pinchot Meyer (29th October, 2014)

Yuri Nosenko and the Warren Report (15th October, 2014)

The KGB and Martin Luther King (2nd October, 2014)

The Death of Tomás Harris (24th September, 2014)

Simulations in the Classroom (1st September, 2014)

The KGB and the JFK Assassination (21st August, 2014)

West Ham United and the First World War (4th August, 2014)

The First World War and the War Propaganda Bureau (28th July, 2014)

Interpretations in History (8th July, 2014)

Alger Hiss was not framed by the FBI (17th June, 2014)

Google, Bing and Operation Mockingbird: Part 2 (14th June, 2014)

Google, Bing and Operation Mockingbird: The CIA and Search-Engine Results (10th June, 2014)

The Student as Teacher (7th June, 2014)

Is Wikipedia under the control of political extremists? (23rd May, 2014)

Why MI5 did not want you to know about Ernest Holloway Oldham (6th May, 2014)

The Strange Death of Lev Sedov (16th April, 2014)

Why we will never discover who killed John F. Kennedy (27th March, 2014)

The KGB planned to groom Michael Straight to become President of the United States (20th March, 2014)

The Allied Plot to Kill Lenin (7th March, 2014)

Was Rasputin murdered by MI6? (24th February 2014)

Winston Churchill and Chemical Weapons (11th February, 2014)

Pete Seeger and the Media (1st February 2014)

Should history teachers use Blackadder in the classroom? (15th January 2014)

Why did the intelligence services murder Dr. Stephen Ward? (8th January 2014)

Solomon Northup and 12 Years a Slave (4th January 2014)

The Angel of Auschwitz (6th December 2013)

The Death of John F. Kennedy (23rd November 2013)

Adolf Hitler and Women (22nd November 2013)

New Evidence in the Geli Raubal Case (10th November 2013)

Murder Cases in the Classroom (6th November 2013)

Major Truman Smith and the Funding of Adolf Hitler (4th November 2013)

Unity Mitford and Adolf Hitler (30th October 2013)

Claud Cockburn and his fight against Appeasement (26th October 2013)

The Strange Case of William Wiseman (21st October 2013)

Robert Vansittart's Spy Network (17th October 2013)

British Newspaper Reporting of Appeasement and Nazi Germany (14th October 2013)

Paul Dacre, The Daily Mail and Fascism (12th October 2013)

Wallis Simpson and Nazi Germany (11th October 2013)

The Activities of MI5 (9th October 2013)

The Right Club and the Second World War (6th October 2013)

What did Paul Dacre's father do in the war? (4th October 2013)

Ralph Miliband and Lord Rothermere (2nd October 2013)